A few weeks back, the same researcher who claimed in 2005 that 0% of men are bisexual released a new study which claimed that 0% of women are heterosexual. It was a bogus conclusion on a few levels. This week, another study about the classification of sexual orientation published in Psychological Science has been making the rounds and was written up on Quartz under the headline “Sexuality may not in fact be a continuous spectrum.”

Alyssa L. Norris and David K. Marcus of Washington State University and and Bradley A. Green of the University of Southern Mississippi analyzed data gathered from 34,643 Americans in 2004-2005 for Wave 2 of the National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. They determined that although women show more sexual fluidity than men, “sexual orientation is not a matter of degree but rather of distinct and meaningful categories.” In other words: heterosexuality remains a very popular affiliation, homosexuality is definitely a thing, and, according to Quartz, “bisexual people, among Americans at least, are relatively rare.” (That last bit isn’t true and wasn’t said anywhere in the study, but we’ll talk about that later!)

This study was really hard for a girl who dropped her double major in Sociology in order to graduate on time to make sense of. It does seem that this analysis was equating “sexual fluidity” with “bisexuality,” though? So keep that in mind going forward.

I should credit our resident scientist Laura Mandanas as a co-author of this article since I took up at least two hours of her life yesterday asking her for help but I don’t want her to be held liable for any mistakes I make in this analysis, so!

On that note of personal confidence, let’s dig in!

What was the point of this study?

These psychologists noticed that there was no consensus on whether or not the “latent structure” of sexual orientation is “dimensional (“ranging quantitatively along a spectrum”) or taxonic (“categories of individuals with distinct orientations.”). This has implications on several areas of practice for psychologists. I guess they feel that it’s important to their work to understand the degree to which sexuality is genetically pre-determined OR the result of a combination of factors (one of which could be genetic) coming together or surpassing a certain yield in a “tipping-point model.” Furthermore, these classifications have implications on how psychologists understand the relationship between sexual orientation and substance abuse and psychiatric disorders. They also wanted to figure out if their own model of determining sexual orientation, which considered several factors — not just self-identification — into account, lined up with this data. (It did.)

Ultimately, I’m not altogether sure that this study was intended to be interpreted and discussed by the press so much as it had implications within the field of psychology.

How solid was the data they were working with?

As aforementioned, this data came from a 2004-2005 survey focused on alcohol and drug use, which also asked demographic questions, including some about sexual orientation and behavior. The interviews were conducted face-to-face using direct questions and flashcards. These are the sexual orientation related questions:

- Which category on the card best describes your feelings? 1) only attracted to females, 2) mostly attracted to females, 3) equally attracted to females and males, 4) mostly attracted to males, 5) only attracted to males.

- In your entire life, have you had sex with only males, only females, both males and females, or have you never had sex? 1) only males, 2) only females, 3) both males and females, 4) never had sex.

- Which of the categories on the card best describes you? 1) heterosexual (straight), 2) gay or lesbian, 3) bisexual, 4) not sure

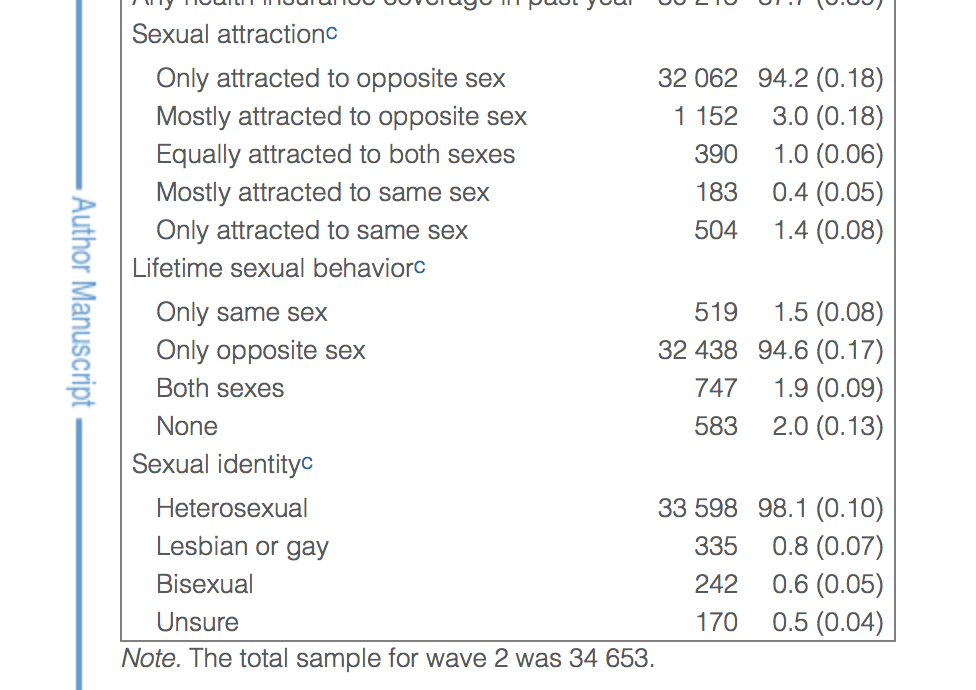

This is how that panned out:

First, you’re probably noticing that the number of humans reporting being lesbian, gay or bisexual are ridiculously low — this happens a lot when people try to count the gays, and you can read more about that here and here. But, as David Marcus told Quartz, there’s really no way around that — “despite this risk, it’s the only way to collect a large enough sample for taxometric analysis.” In the Marcus / Norris / Green study, the researchers also acknowledge that the lack of a “mostly heterosexual” option for sexual orientation is a limitation on analysis, but also say that that limitation was “offset by the large size of the NESARC data set.”

Also, the youngest age group surveyed, 20-24, accounts for only 7.6% of the total set, and multiple studies have found LGBTQ identification and same-sex sexual behavior being more common in younger age groups. 19.3% of the sample were over 65, 34.6% between 45-64, and 38.5% between 25-44.

The Norris Study didn’t analyze data from all 34,653 subjects. As they said in their report, they removed the responses of anybody who hadn’t answered any one of the identity, sexual behavior, or sexual attraction questions, as well as the 583 people who’d never had any sexual experience at all. In total, 1,128 people were excluded from their sample, and it’s possible, as Laura Mandanas noted on this article about gay population statistics, that among those who didn’t answer sexual orientation/behavior questions, “there’s a good chance… they didn’t answer specifically because they’re queer.”

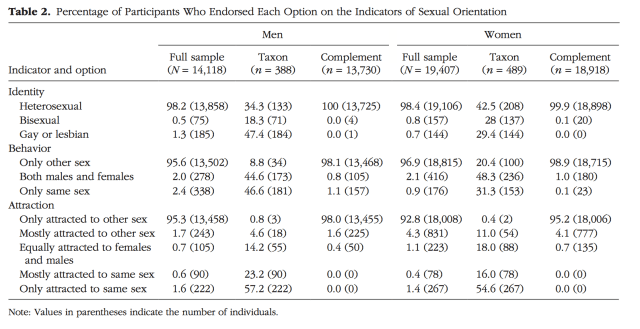

Here’s the numbers Norris and her team used, then, for their analysis:

You’ll notice the “not sure” category no longer exists. That’s 170 people who could very well be the most sexually fluid of them all, so it’s too bad that they had to be thrown out. It’s also interesting that 2.4% of men report exclusively having had sexual activity with other men… yet only 1.8% report being gay or bisexual?

It’s important, however, for researchers to be conscious of the social/cultural climate under which this data was collected. These were face-to-face interviews, for starters, and researchers have since determined that you get much more accurate numbers about LGBT people from completely anonymous surveys. Plus, it was conducted over ten years ago, and although that’s not much time, it’s a LOT of time w/r/t acceptance of LGBTQ folks in America as well as public discourse around things like bisexuality. Honestly, I’m not even sure what I would’ve said had I been interviewed about my sexual orientation in 2004 — since I’d never had a girlfriend at that point, I probably would’ve said I was straight, even though I’d hooked up with girls and knew I liked them. I had nobody to talk to about my identity and therefore lacked the confidence to articulate it.

Furthermore, by the time respondents were asked abut their sexual orientation and behavior, they’d just sat through a significant number of questions about alcohol and drug use, health and family history. It’s possible that respondents were less likely to report what society considers to be deviant sexual behavior after, say, disclosing unflattering information about their mental health and drug/alcohol use — especially if you’re a parent or want to be one, as queers have historically had to oversell ourselves to prove we’re capable of raising children.

So, although the analysis of the interconnected nature of these numbers is relevant to the researchers’ aims, for us, drawing any real conclusions about the size of the LGBQ population based on these numbers would be a stretch. Like, for example, Quartz saying that “bisexual people, among Americans at least, are relatively rare.” In fact, pretty much every other study conducted in the 2010s had bisexuality showing up as more prevalent than homosexuality — a 2011 Williams Institute study found that among those who identify as LGB, bisexuals compromise a slight majority (1.8% vs. 1.7%). National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys conducted from 2003-2010 found 2.3% identifying as bisexual and 1.5% as homosexual. The General Social Survey found 2.2% bisexual and 1.5% gay or lesbian in 2012, and 2.6% bisexual and 1.7% gay or lesbian in 2014. A 2014 survey of 2,314 millennials found 4% bisexual, 2% gay, 1% lesbian and 3% refusing to identify.

What Did The Researchers Conclude?

The researchers were looking for the relationship between attraction, identity and behavior. They found that for men, experiencing same-sex attraction correlated with how they identified, but not necessarily for women.

The researchers determined that it is valid to categorize people as homosexual or homosexual. Turns out that when people say “I’m homosexual,” they’re telling the truth. Anyhow, this is in opposition to Kinsey, who felt very few people ranked definitively on either end of the spectrum, or people like Dr. Chris Donaghue, who told Mashable, “I hope to see more people identifying as fluid both in sexuality and gender, because most of us are.”

Welp.

I think what confused me most about this research was that based on my own entirely anecdotal and completely non-scientific methods largely consisting of “engaging with the female LGBT community intensely for six years and hearing everybody’s story,” I thought we already knew the answer: lots of people are straight, many people are gay or lesbian, and many people are not gay or straight. And, for many LGBTQ people — but not all — there is a genetic factor, and that genetic factor can be the singular determinant of orientation, or just one of many factors that go into one’s sexual orientation. (personally, I see myself as “bisexual by birth, lesbian by choice.”) There you go! All done! YOU’RE WELCOME, SCIENCE.

No but really, Lisa Diamond, the most outspoken scientist on the subject of sexual fluidity, doesn’t claim that everybody’s sexuality is fluid: “There are gay people who are very fixedly gay and there are gay people who are more fluid, meaning they can experience attractions that run outside of their orientation. Likewise for heterosexuals. Fluidity is the capacity to experience attractions that run counter to your overall orientation.”

Maybe all these contradictory studies show that there will never be a complete, specific picture of how sexual desire, attraction and behavior interact, or how fluid or rigid it is. I’m profoundly uncomfortable with studies that do claim to prove one or the other — that sexual orientation is always fixed or always fluid. The “always fluid” model, which is usually discussed specifically in the context of women, suggests that all women are capable of having a romantic and sexually compatible relationship with a man, which gives power to the Ex-Gay Conversion Camps, to reparative therapy, to “praying away the gay,” to forced marriages and, in the worst cases, to corrective rape. It’s also a belief that encourages straight guys to aggressively pursue women who’ve made their non-interest in men apparent, or for families to view their child’s same-sex relationship as something they can “fix.” Meanwhile, believing all sexuality to be fixed is a massive act of erasure.

Sometimes, in a rush to expand our collective minds and promote inclusivity, massive generalizations like “all sexuality is fluid” are made, usually by very well-intentioned people. It’s important that sexual fluidity be understood and de-stigmatized. But we should be able to recognize, discuss and embrace people with spectrum-based sexualities and life histories without needing to claim that all people identify that way… and vice-versa.

Sexual fluidity is a thing and so is bisexuality. So is homosexuality. So is heterosexuality. All of these things can co-exist and be recognized without one needing to describe everybody, and your particular gender identity and sexual orientation don’t need to be universal in order to be valid.

In conclusion, don’t believe everything you read on the internet.

Comments

In other news, non-binary people also exist!

i know right?

Hi!

Riese, you are way too modest. This was a really thorough, engaging, and interesting overview of this study and a lot of the related research. I especially really liked your explanations of the possible factors behind so few people choose to identify as gay–that was so interesting and thorough. They should have you as a study design consultant!

WELL THANKS! (and thanks to Laura, too, who helped me understand it!) I just hate putting something up that I’m not 100% confident about — though I’m confident in my understanding of the 2004-2005 data, I’m not super confident about the results of the 2015 analysis of said data, so I’m just preparing myself for somebody to march in here and be like “NOPE”

I think it’s an open secret that a lot of science papers really are kinda BS that don’t say anything, or say very obvious things and use jargon to disguise that fact, and only the most devoted Kool-Aid drinkers in any given field would argue with that.

But I’m a science-y person in a different field than the one here, so I don’t know if this is one of them. But you have me convinced, anyways!

Herm herm, not all sciences are alike. But although I want to say that my field (biological science) is the exception, there is bullshit in every field. That doesn’t mean “don’t trust any scientist” thought; that’s where climate skeptics and other “science skeptics” get their power. It’s safe to say that social science research is complicated and the data can be looked at in many different ways, for better or for worse, so the prizes go to those who come up with the most headline-captivating research.

Also, that cover image

It’s really annoying that these studies exclude asexual as a category. Like yo, we exist. Also, considering our (estimated*) population size, we could be fucking with your statistics since you’re not giving us the option to y’know choose the correct sexual orientation.

*And it’s really an estimated size because the majority of these studies don’t include us.

Hmm surveys on sexual orientation and behavior have generally found found that less than 1% of people report not experiencing sexual attraction, I don’t think inclusion of asexuality in other surveys would really change the findings that much.

If you’re interested in reading more about these surveys: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/19419899.2013.774161

Just like how surveys show that queer people are a very small percentage of the population?

I think the more likely explanation is that either (a) including asexuality would not be helpful to their model and so they ignored it or (b) asexuality is less discussed/taken less seriously (a lot of people still view it as a “sexual dysfunction), so they either didn’t think about it or didn’t think it was legit enough to include.

(I accidentally like your comment, but really, queers and subset of queers are all often surveyed to be such a small subset of the population that you can’t at all say for sure that it would affect your analysis of bisexuals and gays. As Dina said)

I dunno, I’m asexual but don’t consider that my sexual orientation. I’m still a lesbian, just one who doesn’t experience sexual attraction.

It’s far from a definitive thing in the asexual community that asexuality is an ‘orientation’ in them same sense as homo/bi/heterosexuality. It might be semantics but semantics is important in studies like this.

I often feel like people in the “all sexuality is fluid” camp tend to only look at sexual histories (usually women’s) and don’t acknowledge the crushing social force that is compulsory heterosexuality and how that plays into our lives. It’s also pretty gross to suggest that all women must be capable of feeling attraction toward men, like you pointed out. Who does that benefit? Men. Get outta here with that bullshit.

Word. I fall into the “had sex with both males and females category,” but there’s no option for “…and really wish I hadn’t”, or “completely did not enjoy myself even a little with dudes”

AMEN

As a bisexual activist I have spent A LOT of time explaining to people who think that by claiming “all sexuality is fluid” they are paying me a compliment that is it actually an insult, because they are denying that my experience is different from theirs in the specific ways I’m trying to name.

News flash: we don’t all need to be the same to be equally valued. We need a world that valued people of many and diverse experiences of sexuality, and that goes way beyond obvious examples like sexual orientation, asexuality, kink and the like.

If a straight person told me “all sexuality is fluid” I would read that as “I am sometimes attracted to people of the same sex.” But given current rates of hipsterism, yeah, maybe they are just trying to sound cool.

It also benefits men to assume that all women are secretly into women.

Gross.

I’d be really interested in a series of surveys that a) include non-binary folks and b) go back to the same set of people who self-identify as sexually fluid (not who are forced into that category because someone else has put them in that box) over time to capture what their sexual fluidity looks like.

Like, I went from bisexual > lesbian > queer > genderqueer/ kind of pansexual?? but that also feels fluid. And I feel like it would be really validating to see what that looks like for other people.

Seconded. But longitudinal research is SO HARD! which is not a reason not to do it, (like at all!) but it is VERY hard to get good, actually acceptable to statistics-on-it data from a longitudinal study. Realistically, it’s super hard to get any actual data from people in face-to-face settings like that, (which Riese touched on) and then add asking uncomfortable self-identification questions on top of it, and it becomes nearly impossible. But I definitely agree that if it could work out, logistically speaking, that would be SO COOL to see the results from!

I went from straight > bi > queer? > gay > bi. I’m probably a 4-5 on the Kinsey scale, and the “fluid” aspect is just about what part of my sexuality do I connect more with on that given day/month? Compulsory heteronormativity made homosexuality feel like a way out, but just because I connect with both does NOT mean I can *choose* to be gay or straight. In that sense, I’m not fluid at all.

Woah, so you’re trying to tell be that not all people are exactly the same? And not everyone feels like I do? I don’t know if I can handle that level of cognitive dissonance.

I saw this headline and was expecting the article to be entirely a parody of these researchers.?

I think an offshoot of Autostraddle for The-Onion-like parody articles is in order.

THANK YOU.

Really glad to see you include Lisa Diamond’s much better research here! I had the pleasure of hearing her present at an academic conference on research into sex, gender and sexuality last spring, and her work is so much smarter than this.

She’s also forthright about how our research on these topics is rapidly evolving–for example, a lot of research focused on men in Western cultures has claimed that male bisexuality is extremely rare, but now researchers in non-Western cultures are finding it extremely common. Those cross-cultural studies are especially important, though challenging to do, given that many other cultures don’t disassociate sexual orientation and gender identity the way Western ones do.

On a purely anecdotal level, my impression from that conference is that a lot of high-quality research into sexual orientation and gender identity in both psychology and science headed up by LGBT researchers has happened in the last ten to fifteen years, but hasn’t made its way to the public in accessible forms. I was particularly amazed at how much research the Canadian government is funding on asexuality, bisexuality, homosexuality, and trans experience.

It’s very exciting, but there’s a real need to translate those findings so ordinary people can understand them. Lisa Diamond talks explicitly about how some recent findings upend ideas the LGBT movements have used in our civil rights struggle, and how we need to reconfigure, because the right wing is reading these studies and aiming to use them. So I’m especially glad to see Autostraddle doing some of that work here!

I too am aware about Lisa Diamond’s research but also about what she says for the media and I can’t agree that she’s completely innocent when it comes to encouragement of damaging myths about female sexuality, and particularly lesbians. For a long time she tried to push the idea that female and male sexuality are completely different, buying into the myth that “no men are bi, (almost) all women are ‘fluid’”, getting interviewed for many articles that tried to portray lesbianism as basically the same thing as bisexuality. Even when she acknowledged that the findings of her longitudinal research showed that there are 100% homosexual women, she tried to undermine importance of that fact in her book.

Now, what’s noteworthy here is that Lisa Diamond identifies as a lesbian herself.

This is really great, thanks for the analysis!

Ten years ago, I would’ve said I was straight, and probably that either I was exclusively or mostly attracted to males. Five years ago, I definitely would’ve said bisexual, mostly attracted to males, and that I’d only ever had sex with men. Now, I shake my head sadly at past me; not to invalidate the bisexuality of women who prefer men, but that is so far from who I am that I can hardly believe how deeply compulsory heterosexuality had me fooled. Nowadays, I would prooobably pick either bisexual or unsure, because I don’t identify with bisexuality so much as queerness and polysexuality and sexual fluidity (because my tastes keep changing and developing!), and I would unfalteringly say I was mostly attracted to females even though gender is bullshit and what the heck does “””females””” even mean. Also, I have since had sex with people of a wide, wide range of genders. So basically, this study is such unfathomable bs I can’t even process it.

Maybe I’ve been interpreting past data differently than everyone else. But the numbers here don’t really say anything different than any other comparable study.

What I think they were trying to prove that most people(>95%) are completely ‘straight’ in attraction, identity and behavior.

There’s still enough of a discrepancy to raise my eyebrow about ‘straight’ people.

For men, 98.2% identify as heterosexual but 95.3% are only attracted to the opposite sex.

For women, 98.4% identify as heterosexual but 92.8 are only attracted to the opposite sex.

This is odd to me because the difference between identity and attraction is larger than the total number of people who identify as gay and bisexual.

and the data for same-sex categories was weird. How are there (1132) women attracted to both sexes to some degree and (267) women only attracted to the same sex; but there are only (157) bisexual and (144) gay identifying women?

I tend to ignore the behavior data a bit because these studies don’t ask if any of the sexual encounters were consensual or they don’t acknowledge that people have sex for different reasons outside of attraction.

The CDC published a study back in 2011. Sexual Behavior, Sexual Attraction, and Sexual Identity in the United States: Data From the 2006–2008 National Survey of Family Growth

For men, 95.7% said they were heterosexual but 93.5% said they were only attracted to the opposite sex.

For women, 93.7% said they were heterosexual but 83.3% said they were only attracted to the opposite sex.

And I’ve heard a lot of gay women complain that sexual fluidity statements threaten lesbian identity. All the statements (and studies) I’ve seen have been aimed at straight women who identify as heterosexual but are attracted to the same-sex and have had same-sex experiences. Sexual fluidity has also been used for people that others would call bisexual.

so from every study I’ve read about the subject, I will agree that most people are strictly heterosexual; but the same-sex data has never made any sense. There’s always a discrepancy in studies between how people identify, their attraction, and their behavior.

My take away is to first go back to Kinsey’s studies to see what he was really trying to say. I think he was just trying to prove that bisexuality existed.

Then I’d like to look again at Diamond’s findings. I think she acknowledged that there were women who were strictly heterosexual or homosexual; but wanted to bring attention to women who showed variation in their lifetime. I think the media and the general public have taken their research to a place they didn’t intend it to go.

“And I’ve heard a lot of gay women complain that sexual fluidity statements threaten lesbian identity. All the statements (and studies) I’ve seen have been aimed at straight women who identify as heterosexual but are attracted to the same-sex and have had same-sex experiences.”

Even recently, when that new study insinuated that “all women are only either bisexual or lesbian, not straight” (since some research on pupil dilation showed that straight women reacted to both men and women, but lesbians only to women), some articles actually erased the lesbian part and talked about how ALL women are bisexual.

And I remember to this day two articles from different authors that used PORTIA DE ROSSI as an example of “sexual fluidity”. Because she was married to a guy before she met Ellen (even though she knew she was gay since she was teenager, right before Ellen she dated Francesca Gregorini, and marriage with that guy had nothing to do with any love or attraction as those writers would know if they did basic research on her — but they didn’t since they automatically though lesbianism = fluidity, while if that was about gay guy they wouldn’t doubt it was just a sham marriage).

Do you happen to have the title of an article that used that data to assume all women were bisexual? My google, bing, and yahoo search came up with pages worth of “All women are gay. Or bi. But never straight ……” I found it odd that many outlets would stick to the script. The only article titles I found claiming all women are bisexual were refuting the claim (in the article they mentioned the lesbian statement) or satire.

And that study didn’t show that lesbians only reacted to women. It showed that lesbians reacted more to women. The lesbians still reacted to male images (in genital and pupil response). It’s neither here not there because sexual arousal is a poor indicator of sexual orientation in women.

Do you also have the titles of the Portia articles? The ones I came across identified her as a ‘late bloomer’. They didn’t mention ‘fluidity’ in relation to Portia. I gather ‘late bloomer’ is an earlier term for the same phenomenon. Though ‘late bloomer’ is only used for women who identified as straight and later developed relationships with women.

None of the articles mentioned the nature of her marriage (sham or otherwise). I haven’t seen any report use separate terms for women who were with men out of obligation and women who were genuinely attracted to their male partners.

“There are gay people who are very fixedly gay and there are gay people who are more fluid, meaning they can experience attractions that run outside of their orientation. Likewise for heterosexuals. Fluidity is the capacity to experience attractions that run counter to your overall orientation.”

If someone’s curious how that makes sense (because how do we define orientation if not as a sum of attractions you experience), here’s short explanation. Diamond defines orientation as “proceptivity” (term borrowed from studies on animals), which means here very generic sexual attraction, or lust, to *just* people, their bodies, motivation to have sex with hot people etc. The lesser emotional or personal connection the more clear-cut it is (since Diamond actually thinks that emotional preferences aren’t hardwired in any way and are not a part of sexual orientation).

Meanwhile “fluidity potential” is in her theory the ability to develop sexual attraction to some “special” person even if you normally don’t lust after gender of that person. That is supposed to happen mostly due to falling in love so it’s kinda similar to “demisexuality”, since demisexuals according to that theory are just asexuals with fluidity potential.