Welcome to Hidden Gems of Queer Lit! This column is for those of you who found the first reflections of your desires in a dusty corner of the library, and for those of you who know that important histories and new ways of looking at the world are nestled in yellowed pages as well as flickering screens. Every two weeks I’ll profile a queer lit title that’s outside of the public eye for one reason or another: obscure, small-press, older, aimed at a different niche, or otherwise underrated. It’s my hope that you’ll connect with some of these books and treasure them as I have.

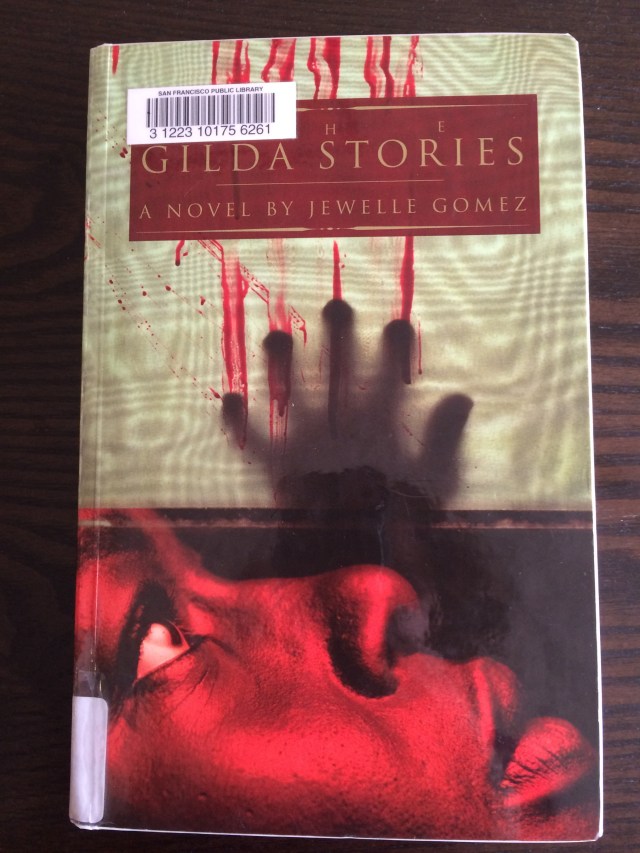

In these next two installments of this column, I’ll be doing something a little different: reviewing by theme, as two fantastic stories featuring queer Black vampires have recently caught my eye. This week I’ll be reviewing Jewelle Gomez’s classic The Gilda Stories, and in the next installment I’ll review Octavia Butler’s Fledgling, which picks up Gilda’s torch and also uses the vampire myth to tackle new themes.

The Gilda Stories was published in 1991 and hasn’t been out of print since. It won two Lambda Literary Awards, one for fantasy and one for science fiction, and was adapted for the stage. It may be a beloved classic, but I actually hadn’t heard of this book until I went nosing around… and I’m betting there are other Straddlers in the same boat. Additionally, its focus on a Black lesbian protagonist is refreshing among all the pale, wealthy men whose stories are most often told in the vampire genre, a mythic terrain ripe with possibilities. For Gomez, these possibilities span the personal, political, historic, and erotic.

Gilda’s stories begin in 1850 and end in a dystopian 2050, creating a coming-of-age story with an excitingly broad scope. Each story is titled with a time and place. In the first, “Louisiana: 1850,” a slave referred to only as “the Girl” flees a Mississippi plantation after her mother’s death. She is taken in by a white woman named Gilda who runs a New Orleans brothel. With Gilda and her partner, a Lakota woman named Bird, the Girl finds a loving home. While some of the women in the brothel are suspicious of their uncanny qualities, the Girl is drawn to them, and voluntarily joins their long-lived vampire family. When Gilda embraces death — a choice for vampires, rather than an imposition — she passes on her name to the Girl.

The new Gilda’s adventures over the next 200 years reveal an original take on vampire lore. Part of Gilda’s initiation into the vampire life is a teaching that Bird and her contemporaries hold sacred: rather than killing humans to obtain nightly nourishment, Gilda must take some of their blood and leave something in return. This is facilitated by the vampiric ability to read thoughts — Gilda can sense someone’s desires and fulfill them as she drinks her fill. If a target is craving power or love, she can give it to them in their dreams; if they’re suffering from addiction, she can embed in their minds the desire to abstain. There are other vampires in the book that kill or manipulate as they feed, but Gilda’s family of vampires considers their own practice to be an equal exchange. This is a crucial aspect of the story for Gomez, who writes in her afterword to the 2004 edition that “for Gilda to work for me and my audience, the vampyres had to break the traditional mold… if I could move the one who provides the blood from ‘victim’ to ‘sharer’ (knowing or unknowing), the nature of the power in the relationship would be different.” This exchange is certainly food for thought, and in a world where we’re all consumers, the taking-and-giving philosophy of Gomez’s vampires may, in fact, be something to strive for. Another twist is that the vampires protect themselves against sunlight and water — both dangerous to their kind — by embedding soil from their birthplace into their clothes and bedrolls. This protective device literally keeps them grounded in their own history. When the environment falls into decay in the final stories, one vampire character notes, “You and me — we’re lucky. We can’t ever forget our dependence on this earth.” Perhaps it’s these dynamics of exchange and groundedness that make The Gilda Stories’ vampire characters so human.

Gomez’s vampires offer her an opportunity to explore Black American life throughout the ages. Each story begins with Gilda interacting with someone, usually a new friend in a new decade. By necessity, Gilda moves around from place to place and job to job. Part of the novel’s pleasure is in guessing what will come next. As an immortal being, Gilda has the opportunity to explore the myriad possibilities of life that most of us only dream of. She tries her hand at farming, running a beauty parlor, singing in nightclubs, and penning romance novels. While her contemporaries relish the opportunity to travel the world, Gilda prefers exploring the U.S. and seeing how Black people live in different times and places. She holds on to memories of her mother, who was taken from her African home to the continent where Gilda was born into slavery. It should come as no surprise that Gilda’s people are important to her. In 1921 Missouri, she inspires a budding activist; in 1955 Boston, she helps sex worker friends take revenge on a cruel pimp; in 1981 New York, she joins a salon of Black artists. Readers witness changing slang, changing fashion (with pants-loving Gilda at the forefront), changing attitudes toward race and politics, and changes in women’s civic freedom. In the early stories, Gilda disguises herself in men’s clothes to walk the streets at night, and her hunting targets subtly reveal the ubiquity of male mobility.

In an interesting take on vampires’ potential for sensuality and otherness, the novel’s vampire communities are coded as queer. Gilda’s “mothers,” the original Gilda and Bird, are a lesbian couple who run a business together. The two vampire men who later become her dear friends are also partners. In fact, only two of the vampires in these stories are straight, and Gilda’s own sexuality is an understated yet important part of who she is. She finds both Black people and queer people (often both at once) to connect with wherever she goes. The novel excels at blurring the boundaries of family, friendship, need, and desire, with scenes of feeding or vampiric conversion skirting the edges of the disturbing, the sensual, and the heartwarming. Gilda’s vampire community cares deeply for its own, with members learning to live among others but maintain a necessary apartness. Its “blood bonds” supersede familial and racial bonds in some ways but not others—intersectionality is done well in this novel.

Gilda walks into the future (which is sometimes prescient and sometimes comically askew) as a courageous feminist with an enviable access to history. In conclusion, The Gilda Stories are a classic for a reason. Check this novel out to experience a masterful melding of history and dreams.