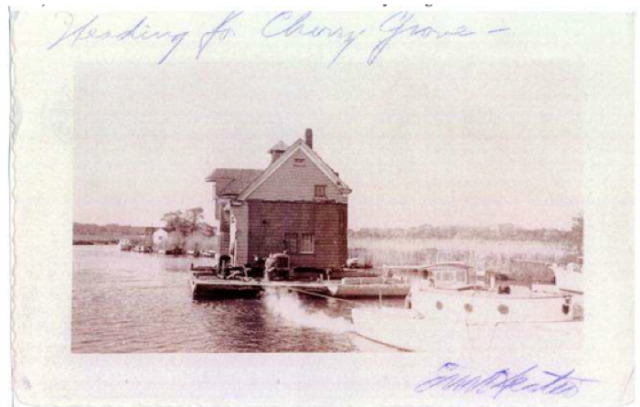

There are about 85,000 individually listed properties on the National Register of Historic Places. Of these, only three directly relate to LGBTQ history: there’s the Stonewall Inn, site of the Stonewall Riots, the Lexington & Concord of the modern American gay rights movement, which was listed in 1999. There’s the Washington, D.C. home of the late Frank Kameny, which was admitted to the register in 2011 after a long campaign by the Rainbow History Project and other local activists (Kameny was an astronomer and activist whose broke a lot of political and legal ground throughout the 60s, 70s, and 80s — he was the first person to bring a sexual orientation-based civil rights suit to the Supreme Court, and the first openly gay person to run for Congress). And there’s the Cherry Grove Community House and Theater on Fire Island, New York, chosen in June 2013 because of “the enormous role it played in shaping what evolved into America’s First Gay and Lesbian Town… facilitating gradual social acceptance, self-affirmation, and integration of its gay and lesbian residents into Cherry Grove’s governing affairs and civic life.”

In 2000, Stonewall was upgraded to National Historic Landmark status, meaning it is officially considered to have played a significant role in the nation’s history. There are about 2,500 National Historic Landmarks, but Stonewall is the only one that’s overtly LGBTQ-related. (For a little perspective, 128 National Historic Landmarks are ships or shipwrecks).

Those numbers seem a little low, right? Fortunately, the National Park Service — the governmental branch in charge of bestowing all these titles — thinks so too. During an October webinar on the subject, a recently formed NPS subgroup, called the NPS LGBTQ Initiative, acknowledged that they are “behind, way behind, on acknowledging LGBT historic sites,” reports Matthew S. Bajko of the Bay Area Reporter. Bajko talked to Megan E. Springate, an archaeology PhD student and queer person who is helping the NPS find and evaluate more places for the register as part of her graduate work. The NPS is “looking to make LGBTQ history part of the national memory,” she explains, but they need the community’s help. “They are supportive and encouraging, but they need people to fill out the paperwork.”

So why are there so few queer landmarks on the Register in the first place? First of all, a lot of people just don’t know how to register a place, or that they even can. Outreach efforts like October’s webinar, as well as a follow-up that should happen later this month, are meant to correct this — as is Springate’s work, which involves developing frameworks that will help citizens nominate queer places specifically. But other problems are more baked-in. For instance, the National Register tends to privilege older places — there’s an unofficial, but commonly accepted “fifty-year rule” that affects whether people even think about nominating sites younger than that. It makes sense — the more time has gone by, the easier it is to justify something’s historical importance (for example, the people who eventually got Frank Kameny’s home registered had to wait until after Kameny died to even be considered). But the American gay rights movement (like most American civil rights movements!) is relatively young, so a lot of important places don’t show over the fifty-year fold.

In addition, registration requires a certain amount of historical evidence that might just not be available. As Springate points out, “People were closeted so there may not be a whole lot of documents. How do you document the lives of people who are trying to be hidden?” And even the loudest, out-est proprietors, organizers, and groundbreakers can’t fight the censorship inherent in gentrification. In order to qualify for the registry, a site must meet seven different “tests of integrity” — basically, it must exist in close to the same form as it did when it “became historical.” So if spots haven’t, historically, been valued and protected, they’re less likely to qualify for historical valuation and protection (although the NPS can’t guarantee preservation of registered places, being listed can help a place financially, both by boosting its public profile and reputation and by qualifying it for tax benefits). Although this also makes sense, it’s a sad catch-22, and one that reinforces existing hierarchies. As Mark Meinke, who got Kameny’s house registered, points out, “One of the problems is that a lot of our historic sites are uniquely commercial, because for decades the only place you could go was a bar. And most of the bars, historically, were in sort of borderline economic areas because it was cheaper and they didn’t mind if there were ‘faggots’ down the street.” If that bar eventually gets bought or torn down, it no longer exists to qualify. And I expect all of these obstacles are compounded for queer people of color, queer women, and trans* people, the way such obstacles are pretty much across the board.

Luckily the NPS has enlisted the help of experts like Springate, university professors/students, and different states’ historic preservation offices to help fix and get around these problems, and to find sites that qualify anyway. But they need your help too! The NPS is pretty good at making it easy to nominate a place to the National Register— the instructions on their website are thorough, and they even accept nominations via PDF now (although you still have to put that thing on a disc) — but the process still requires enough information, brainpower, and grunt work that it might be best to tackle this with your local LGBT group, as a class project, or maybe with the help of your fellow Autostraddle community members after a passionate discussion begun in the comments to this article (just saying).

Such discussions have already started elsewhere — Queerty would nominate “Cole Porter’s house in Williamstown, City Lights in San Francisco, feminist printers Diana Press in Baltimore, [and] Running Eagle Falls in Montana,” among other places. Mark Meinke wants James Baldwin’s house and “D.C.’s LGBT community space at 1724 20th St. NW.” Various Autostraddle staffers have suggested “Riese’s living room,” “the seat Michelle Rodriguez occupied at the Knicks game,” “Angelus Oaks Campsite, Falcon Lodge,” and “the jail wall that Bette had sex with on The L Word.” Some of my suggestions are in this article’s photo captions.

So: where do you think deserves Historic Placehood? We’ve been invisible long enough — let’s get cracking!

Comments

THIS IS FANTASTIC. In my queer theory class we talked about how most of queer history is overrun by gay men and that lesbians’ contributions are mostly not really talked about or seen as significant. So this is important, both for lesbian me and the next generation of little baby lezes looking for people like them in history.

This is wonderful!

You’re absolutely right. Public history is sorely lacking a significant LGBTQ presence. It is and should be appreciated as part of this country’s history. Hopefully promoting this kind of awareness does some good.

Some portion of Alpine Meadows will be there, at some point. I really do think so.

This is so cool!

Sarah Orne Jewett (September 3, 1849 – June 24, 1909) was an American novelist, short story writer and poet, best known for her local color works set along or near the southern seacoast of Maine. Jewett is recognized as important practitioner of American literary regionalism. Jewett never married; but she established a close friendship with writer Annie Fields (1834–1915) and her husband, publisher James Thomas Fields, editor of the Atlantic Monthly. After the sudden death of James Fields in 1881, Jewett and Annie Fields lived together for the rest of Jewett’s life in what was then termed a “Boston marriage”. Some modern scholars have speculated that the two were lovers.[11] In any case, “the two women found friendship, humor, and literary encouragement” in one another’s company, traveling to Europe together and hosting “American and European literati.” Exert from Wikipedia link : http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sarah_Orne_Jewett

I live about 5 miles from her home, which is a historical landmark in the center of the town of South Berwick Maine.

I am a self-proclaimed history nut. I would love to be involved in this project to any degree of which I may be of use to you. I submitted a link to Sara Orne Jewett’s Wikipdia entry, she was a local poet in the early 1900’s here in southern Maine, and I live about 5 miles from her historic home. She was in what is called up here a “Boston Marriage”, the early term for a lesbian partnership,with another novelist named Anne Fields. She was a very outspoken and interesting local character here. If you are in need of research, writing, photography or whatever for this project please do not hesitate to contact me. I subscribed to your newsletter, so I believe you have my email info already. Thanks for this website and all you are doing here! ~Angie L.