There comes a time in the lives of many young, married couples when their thoughts turn to starting a family. Then, assuming that they’re a queer couple without access to home brewed semen, they find out about the laws relating to artificial insemination and instead construct a fort out of pillows and back issues of The Advocate, never to emerge again.

Did you guys know that in many states, if a physician doesn’t conduct the insemination, then the parental rights of the sperm donor might not be terminated? This legal loophole has recently been used against a lesbian couple in New Jersey, whose sperm donor is suing for parental rights despite having signed a contract giving up these rights, and a sperm donor in Kansas, who may be forced to pay child support after providing sperm to a lesbian couple. (See? These laws hurt everybody — even straight guys attempting to share their sperm with lesbians through the magic of Craigslist!)

Perhaps my wife and I are more naïve about the legal system than your average queer dyad, but when we first read about the New Jersey case we were pretty much gobsmacked. We’re not planning to become parents for another couple years or so, but in the meantime we’ve been saving money in a baby fund, discussing the pros and cons of adoption vs artificial insemination, and generally preparing the way for us to start a family. We’ve also thought a fair bit about the ways in which doing so might be complicated by the state we land in after my wife starts on her PhD (she’s currently working towards a MS in entomology). But our rule of thumb had always been blue state=good, red state=bad — that is until we read about the couple in New Jersey. Although we’d likely have gone through a sperm bank rather than using a known donor, we’d certainly never planned to inseminate inside a sterile doctor’s office. And frankly, even if we take all the precautions necessary to avoid this particular problem, it’s been more than a little terrifying to consider all the other things we might not know about the way the law will treat our family.

The presence or absence of a physician may seem arbitrary now, but most of these laws date back to a time when lesbians inseminating at home as a couple simply wasn’t on the cultural radar. The standard text, which is found in many of these older statutes, reads:

“If, under the supervision of a licensed physician and with the consent of her husband, a wife is inseminated artificially with semen donated by a man not her husband, the husband is treated in law as if he were the biological father of a child thereby conceived. The husband’s consent must be in writing and signed by him and his wife. The consent must be retained by the physician for at least four years after the confirmation of a pregnancy that occurs during the process of artificial insemination.”

There’s an awful lot to be worried about with that wording. In addition to relying on the presence of a physician, it goes on to assume the existence of a “husband” to whom the rights and responsibilities of fatherhood are transferred. Still, that doesn’t mean it’s the worst that’s out there — in South Carolina sperm donors are actively encouraged to claim paternity through something called the Responsible Father Registry, and in Georgia (and possibly in other states as well, according to Beth Littrell at Lambda Legal who I spoke to for this story), anyone other than a doctor who conducts an insemination may be guilty of a felony. Littrell went on to emphasize that even in states where a physician’s presence is not required in the law, heavily gendered language is often present which may complicate the situation of same-sex couples. Lambda Legal is currently pushing for gender neutral interpretations of the laws, but as things stand the legal status of married same-sex couples is not settled.

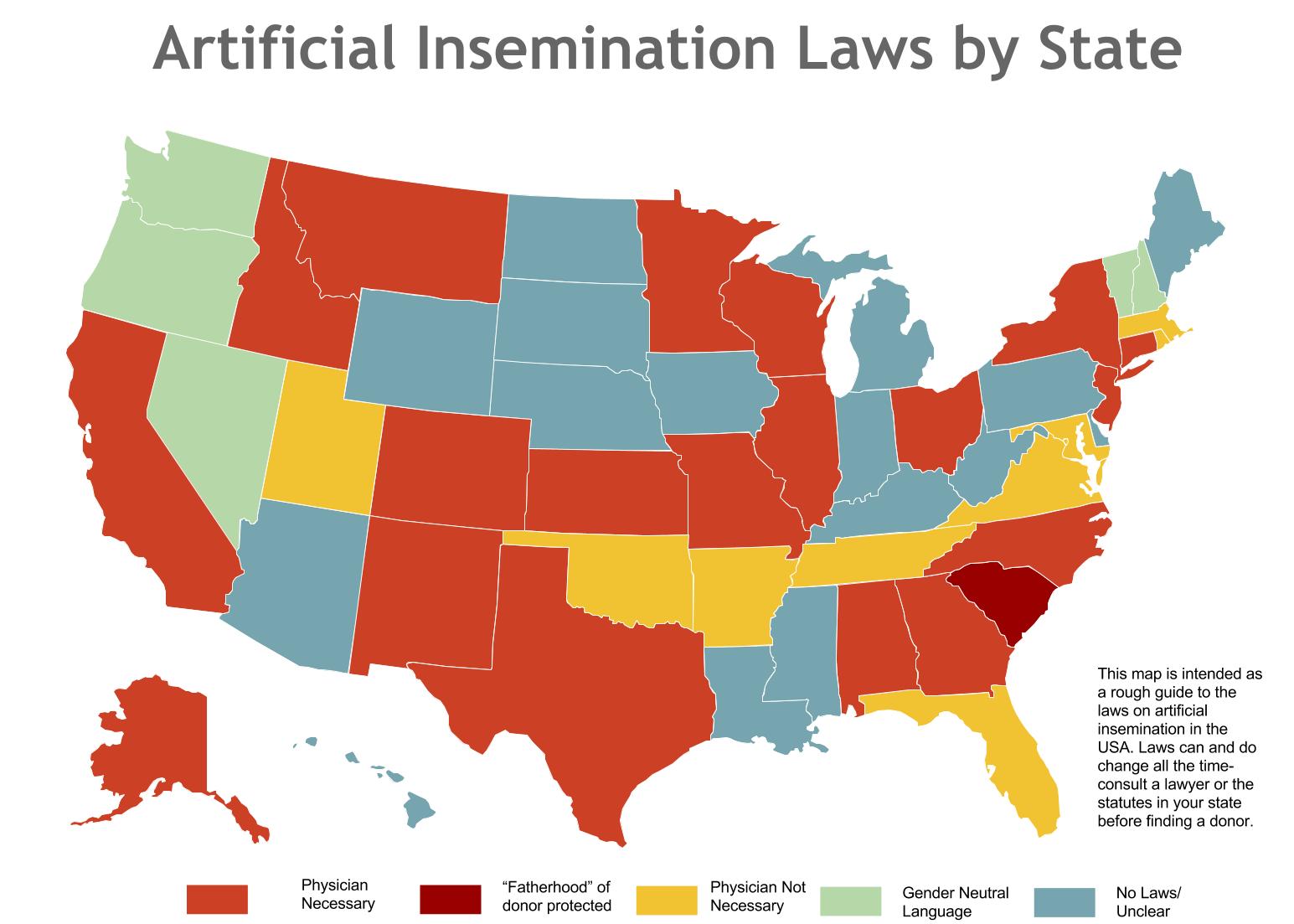

In all, there are twenty states who’s laws require a physician to conduct an insemination before the donor’s rights to be terminated, (although in some of these this loophole hasn’t been enough for a court to grant paternity to a sperm donor). In a further nine states the language of the law relies on gendered terms like “husband “ and “father”, and in many other states there are no laws dealing with the paternity of donors in the first place. In fact, there are only five states where gender neutral language exists to protect the rights of queer couples seeking to conceive with donor sperm (these are New Hampshire, Vermont, Nevada, Washington, and Oregon).

Most of these laws shouldn’t have any bearing on couples that locate an anonymous donor through a licensed sperm bank — such facilities have mechanisms that protect both the donor and prospective parent(s) from unwanted legal complications. Unfortunately this means it disproportionately disadvantages lower income folks, who may try to find their own donor and eschew involving a physician to keep the cost down. It’s also really hard on couples who’d like to get to know their donor personally before inseminating, many of whom would rather conduct the insemination in a more intimate setting than a doctor’s office.

If same-sex marriage becomes the law of the land, then there’s an excellent chance that gendered language for married couples won’t withstand a challenge in a federal court, especially with attorneys like Littrell fighting for the good guys. But the requirement that a physician be the one to perform insemination is a trickier animal, one that will require sustained advocacy at the state level to ensure that better laws are written. Ideally, these laws would balance the rights of queer couples (and single parents), with the protection of children and the rights of fathers who do not wish to terminate their rights, to arrive at a clear and equitable legal framework for all parents. For anyone who thought their rights would be fully protected once the reach of same-sex marriage went everywhere, bad news —the struggle for equality under the law continues.

Comments

How is the treatment for sperm donors not identifying as male our of curiosity.

This isn’t something I’ve personally looked in to, yet. I do know that federal law bars gay men from donating to sperm banks (although they can donate personally to someone they know), and my hunch would be that donors that didn’t ID as male would have an uphill battle being accepted as an anonymous donor by a sperm bank (there are some that don’t take men shorter than 6′, and most don’t accept sperm from non-college graduates, so they’re not exactly bastions of diversity and progressive thinking). However, a private arrangement would be a different story- I doubt the gender identity of the donor would be an issue in that case.

My wife banked some of her gametes before starting on medications for her transition. The doctor we are seeing now as we try to conceive said she has suggested to other patients of hers that they might want to bank some material before transitioning. She tells them in general terms using us as an example, which I think is pretty cool. So there might be reasons to bank material for later personal use.

I think that would be a really great idea. I know of several trans women who have expressed the wish that someone counseled them on that possible option before they began their medical transition. One problem, of course, is the expense of maintaining the material for what could be years, especially when the person is not in a relationship.

We have been paying $40 a year, I believe, to store the material, which isn’t bad.

I’ve attended the Trans-Health Conference here in Philly for the last few years and their recommendations are to always counsel to store gametes before medical transition. Hopefully more and more docs will start doing that routinely.

But that storage cost is a big factor! $40/year sounds great. We’ve been paying $200/year for years in case we decide to have more kids with the same donor.

Thank you for this amazing post! Just curious to see if you know of any updates that might have happened since this was published?

This was so so so super helpful! I want to send this to every person who has either implied that getting knocked up is going to be super fun and easy for us AND every person who has asked us how we are “doing it.” Making a baby is a really loaded and personal topic for LGBTQI people who can’t conceive through intercourse (because of course some LGBTQI people can). So much harder than just smushing our private parts together and near-impossible for some to do so in a way that is validating and fair.

This article was a great start, but to me it seems like an oversimplification of the legal landscape.

There is a huge distinction to be made between “the rights of sperm donors do not terminate automatically” vs “sperm donors can choose to terminate their rights” vs “sperm donors cannot terminate their rights”.

There are also so many other factors involved, including the availability of second-parent adoption in a particular state, that will affect the specific legal outcomes available and the different paths you could take to get there.

Of course the law is more complicated than one article can portray. That should be a given. It doesn’t make the information that IS there less useful, unless the information is wrong.

Agreed. There are also legal and equal rights issues in regards to public assistance. If you need to go on public assistance, you will be asked to declare the “father” so they can go after them for child support. If you do not name a “father” they can deny you services. I am a single mom by choice, so it would be a similar legal situation to a lesbian couple whose relationship is not recognized in their state. I was told that I could not get assistance because I got pregnant on purpose (I ended up losing my job after I got pregnant, and because of it) and was then referred to a child support person who harassed and bullied me for half an hour. I had to say that I did not know who the father was and was told that if I don’t find out the name of the person I sleep with in the future and have another pregnancy they would not help me. It was really demeaning. So, if a couple who conceived via donor sperm, specifically a known donor, has to go on assistance, they could be pressured to divulge the name of their donor. Known donor contracts are dependent on trust to not have to end up in court because they don’t necessarily hold up even if they are written up by a lawyer and signed in front of a notary. I could get the donor to go to court with me and get his “parental rights” terminated but it could open us up to more problems. The judge could deny our request, force him to pay child support, and force me to allow visitation even if we are not interested in doing so!

What if one or both of the partners is a licensed physician?

this is a really interesting question!

In my grad program for child development who had to do a paper on parenting in different cultures and interview four families from a culture different than our own. One student received permission to interview queer parents. One of the couples did include a medical doctor so they stored the material in their freezer and were able to do the insemination at home, I believe.

diy insemination and original maps! ALL AT ONCE! this is a great article.

it also made me think about what Terry Boggis talked about at the Invisible Lives Targeted Bodies conference. She spoke about how it’s gotten harder to do inseminations without the intervention of doctors and tied it into reproductive justice. I’m linking the video below. She starts talking around minute 6, but Reina Gossett and Cara Page’s parts are also brilliant and super relevant to this conversation, so why not watch it alllll

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B99HtltgCRE

Last weekend, I heard Nancy Polikoff (a rad law professor) talk about how same-sex marriage fails to provide legal recognition for all kinds of queer families and so this article is so timely because I was wanting to know more!

One thing I learned in hearing her talk was that my assumption (that the legal recognition of same-sex marriage meant recognition of parents rights) couldn’t be more wrong. Apparently, the parenthood/marriage statutes are so strange and vary so widely state-by-state that allowing same-sex marriage really just means that now we have to deal with those same, insanely complex laws.

“Most of these laws shouldn’t have any bearing on couples that locate an anonymous donor through a licensed sperm bank — such facilities have mechanisms that protect both the donor and prospective parent(s) from unwanted legal complications.”

OMG you were really freaking me out until you got to this part. You really should have lead with this!!!

I live in OR, but OR is can be a difficult state to live in sometimes. It may not be forever. I comforted to know sperm banks still provide protections should I move.

I absolutely want ZERO relationship to my donor and while I would never sue for child support, cause what decent person does that, I would like to know he has protections too. Everyone should have legal protections!

Yeah i’d like to know why that lesbian couple sued the sperm donor for child support. Like did they need money, or are they just being silly.

I believe it was the state of Kansas, which decided to go after the sperm donor rather than the ex-girlfriend for child support after the gestational mom fell on hard times, because homophobia.

Yup, the state child support agencies can force a person to declare the “father.” You have to say you were drunk and it was a one night stand, etc. There is no provision for donor conceived children whose parents end up needing assistance.

Insemination isn’t where it ends, either. When our daughter was born, before we could get a birth certificate including my name AND my wife (then partner)’s name, I had to sign a set of papers that stated: 1. I was the egg donor, 2. I was the person who had carried this child to term, and 3. I intended for myself and my partner to be the parents of this child. Because there was apparently no system in place for lesbian-gives-birth-to-child-she-plans-to-keep. And this was after enduring a lecture and continuing disapproving looks from the postpartum nurse when I refused to list the sperm donor on my daughter’s paperwork.

Wow, that paper almost seems to take away your rights. You go from biological parent to egg donor/surrogate for no real reason.

I thankfully didn’t have to deal with that. My midwife new my son was donor conceived and I believe the nurse who did his first check after birth was family. When the birth certificate people brought me paperwork, I just left father blank and was never asked about it. Not sure how that would have been different if I had a partner.

This is so stressful. I always thought I’d want to use an anonymous donor for a plethora of reasons, but after I met my significant other and we’d been dating awhile, I realized I REALLY want to have their babies. But obviously that’s not something that can happen. Next best thing is using their brother and their brother is on board. But I’ve made it VERY clear that I don’t want him to have any sort of father figure role in my children’s lives. I don’t want him to be the godfather or anything like that. And it stresses me out that he could fight for legal rights to my children.

At the same time, if I couldn’t get pregnant and so we switched to trying to knock up my person, we’d use MY brother, and it stresses me out that he could argue for more legal rights to my kids than me.

C’mon, scientists. Make it possible for there to be no need for sperm in procreation, for a gazillion reasons. Please and thank you.

I like the idea of my children being biologically related to my partner, I think many people do, but mixing personal and legal always seem like shaky ground and when that ground seems to be heavily biased toward heterosexual families I couldn’t risk it. Also, even if you won there is the the family relationship at risk. It’s like loaning money to family, but the stakes are even higher.

Yes, exactly. I’m not *too* concerned about my brother or my partner’s doing anything stupid, BUT what about their future wives? What if the wives have fertility problems and get so desperate for a child they convince their husbands (our brothers) to go after mine????????

For some of the reasons you’ve mentioned, my preferred option (we’re a year or two away from this) is to have IVF With an unknown sperm donor and partner to partner egg donation so I can carry my partners child. waaay more expensive than other options though (I’m in the uk)

I’ve always sort of fancied that idea but 1) it’s so damn expensive and 2) I wouldn’t want my partner to go through the egg retrieval process just for funsies. I’ve told them how sucky it was when I donated eggs (and was jut asked today about donating again…ugh), and it is NOT fun for either party. I’m the product of IVF and so I also have feelings about that.

You would all go to court to get his rights terminated and do a second parent adoption for the non gestating parent. You set it all up beforehand and do it as soon as the child is born. There are some ways to protect all parties involved but it does have to ride on trust for a bit. The legal fees are an unfair expense but worth it. That is all dependent on what state you live in too.

This is an important article with information but as someone who has no interest in bringing more small humans into the world and would rather focus on parenting/supporting the parenting of those who are already here, I am equally excited that Geoff’s sister is now writing stuff on Autostraddle as well as The Toast!

Hi, Geoff’s sister!

Hi!!!!

As a trans woman, I’m actually kind of morbidly curious what the laws would make of my situation, since in the near future I’ll be considered legally female *but* my partner and I plan to conceive at some point using sperm I had stored. Would I still have paternity?

They way the laws are written biological parentage is the pinnacle of rights. A confirmation of gender identity doesn’t change your genetics or the outcomes of testing. I haven’t read any cases around transition, but I doubt that would be an issue unless/until you and your partner split. At that point every hateful bias you could imagine might be used against you to make you seem like parent less beneficial to the child, in other words like every other custody case just worse? Might be useful to seek legal advice ahead of time.

I’ve wondered a bit about this as well. The fertility clinic we go to has been pretty good about understanding the situation but how much would depend on the time of the delivery? And ensuring that the midwife or if there were complications that the hospital puts the correct information on the birth certificate?

Also Tessa, good luck!

Ugh, the gendered language of parental laws is so terrible. I also don’t like that (from what I’ve seen in my searches) you can’t list the donor number from the sperm bank under Father’s Name on the birth certificate, you have to say the father is unknown. Which is not really accurate either.

I don’t think I’d want a number listed on the birth certificate. Having one legal parent (I’m in a no second parent adoption state) makes things like travel easy.

Yea, the donor number is important because the child has a family medical history. And there is also the incest concern in the future.

The family medical history can be passed down orally like in any family or by showing the child the paperwork. The donor number doesn’t really contain that much information.

About incest concerns, I would think anyone who knew they were conceived with a donor, who wanted to date someone else who was also conceived with donated sperm, might do a little investigation. With the donor sibling registry, that seems like less of a concern.

So, like, my kids have dosies (donor siblings) in a couple of states and a few countries. We know who they are and they know who we are. They all have enough of a resemblance that I doubt it would go unnoticed (“Woah, you’re hot enough to be my sister!” Ummm).

On the other hand, the birth certificate is a useful document for the people who are actually parenting.

It seems like a lot of straddlers would prefer and anonymous donor. This is interesting, because I would much prefer a known donor, and I would like the child to have a relationship with the donor. In a best-case-scenario my child would have a dad (or two!) in addition to two moms. Most commenters here are American and I’m Finnish, so I guess this may not be just a personal difference but also a cultural one? I would like the dad(s) to be gay, so this is an altruistic thing as well – having children with lesbians is almost the only way for Finnish gay men to become fathers. Surrogacy and gay adoption are both illegal here.

In an ideal situation I would adopt. There are so many people in the world already! I long for a family, not for biological children. (Isn’t it almost funny? Usually people who can’t conceive are told that there’s always adoption, as a plan B.)

I just want to raise a child with my partner who I love, not with the addition of some random guy who matches our gene profile…

If I wanted the donor to be a “random guy who matches our gene profile” I would go the anonymous donor route for sure. I don’t even know what a gene profile is. Is it choosing a donor who has the same ethnicity/eye color/etc. as me? I don’t care about that kind of thing. I care if the person is going to be a good parent. Where I come from queer families often find “parenting partners” – you platonically commit to another person, a friend, to raise a child together. If we don’t find the right person to co-parent with we might choose anonymous sperm after all. But it’s not what we prefer.

Maybe this is a foreign concept to you but please be respectful. Parenting choices are very intimate matter and the tone of your comment felt a bit passive-aggressive.

I have heard of similar arrangements between gay and lesbian couples in the U.S. The children have 4 parents and everyone gets a parenting relationship with women and men. Legally, it works because the partners are legal steparents and if each couple has 2 kids each adulthood gets biological parenthood. I think my partner and I would agree to such a situation. If we were quite close to a gay couple.

But I see how it could strain the acceptance of extended family and who might a struggle with the idea of lesbians having kids. And of course, if there were disagreements or divorces parental rights would be difficult to deal with in a homophobic court.

Yes, I definitely think it’s cultural! The idea of an unknown sperm donor was always a bit strange to me, when I was younger I had the feeling that it was originally made with ashamed straight couples in mind (but now I know the advantages for some queers!)

Probably cultural.

Artificial insemination for lesbians isn’t legal in Germany, but while Denmark or the Netherlands are like a two hour drive away, nobody I know of has ever considered it.

Close friends are usually considered, or gay friends and couples.

You do joke about it with your gay friends, to see who’d be available,who wouldn’t, as you said, they don’t get to have kids otherwise.

There are even ads in queer magazines, detailing the amount of fatherhood desired for the donor.

A few years back, giving sperm to your Lesbian bestie was considered an honorary gift.

Then there was this court order, which obligates a biological father, regardless of any paperwork signed, to pay for his offspring.

Since then,I feel that only guys who want to be involved with the kid’s life in any way are signing up to pitch in.(Pun intended).

The arrangements differ widely, of course.

We call them “Rainbow Families”.

Many gay people would love to adopt, I certainly would, but due to discrimination it’s easier to (at least for lesbians) and less costly to have our own. Artificial insemination is a lower barrier than trying to compete with heterosexual families at adoption agencies and much less expensive than international adoption, which is not feasible for many.

This is the case for my partner and I. We’re on a real journey looking for a sperm donor – we’re defining the role as ‘kind of like a distant uncle’ – we want our kid to have contact with him, to know who he is, but for him to have no influence or decision-making responsibility.

We’ve been searching for a while and have tried different routes. We have talked about using an anonymous donor via a professional sperm bank but that’s our plan B, we’re still holding out for plan A right now, though it’s more complicated.

Wow this is so complex, I believe it’s much simpler in England…not sure about other countries in the UK. Laws vary by country.

Although when gay marriage was legalised there was some confusion over if there were parental rights differences between civil partnership and marriage…there aren’t apparently.

Good luck making babies American Straddlers!

I hope you’re right about it being simpler in the UK Hat! I genuinely hadn’t considered this kind of legal situation – will be doing some research this week!!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aOt_o0WdYzc

The law seems pretty clear in the UK. Basically, do it after 2009, be married/partnered and don’t actually have sex with the donor and you are hunky dory. Don’t meet these conditions and the donor is the father. No grey area.

My wife and I have decided to choose a sperm donor we will share and take from the bank for each child. We hope for 1 each, but that may change. We’re choosing a donor that will allow for contact after the age of 18. It’s an exciting and frustrating time!

Reading stuff like this is so asffshkjek bc like, wow! I had no clue! but also, where the hell can I live and be sure some rando cis dude isn’t gonna try and claim my baby?

Welp, never getting pregnant now because I live in Ohio and I hate doctors and I hate men and I hate everything why is the world like this let’s just secede start a queer island where the laws make sense and don’t rely on old-timey paternalistic bullshit.

In my dreams I imagine a world where all of us take Over some desserted Island abd live in our own stradler Country… with Riese as president of course!

My wife and I got pregnant at the dr’s office. We did this because friends of ours spent GOBS of money on sperm from a bank while unsuccessfully trying at home, and ended up getting pregnant a year later after one time at the Dr’s. We were worried it wouldn’t be special getting pregnant at the Dr’s or it would be weird to screw in an exam room. We ended up having mind blowing sex the night before, and for us that’s the our baby’s real conception.

Also, we decided to use a known donor; a friend of ours who is straight and married and nether of them want kids, but both of them believe my wife and I should be parents. We went with a known donor 50% because of the cost of sperm and 50% because we would know the character of the man. We had to do a mountain of paperwork: he had to give up parental rights when he gave the sperm and every time a child is born of that sperm, I had to adopt the child my wife bore, and she will have to adopt the child I bear.

I think the fact that it’s such a hassle and major pain in the ass is what makes us such good parents. We really have to want it.

Amazing Post! My fertility coach, Lin Weinberg at http://www.yourfertilityguide.com and spokenorigins.com suggested this post to me and I’m so glad she did. I didn’t know anything about known sperm donors as an option until I met her. I’m going to share this post with a few friends who I know will benefit.

I’m happy to live in a state where when using a fertility physician automatically servers the rights of the donor, known or not. Yet at the same time, It’s an added expense to an already expensive route to having a child.

Thank you again for such a great post. Very informative.

Is this still current? OMG this stuff is scary! My partner and I are thinking about getting pregnant soon and this is so scary!

What is scary? If you have the help of a known donor, then you need to research your state’s laws and process for terminating rights. You also would need to talk to a family lawyer and see if there are any other things you need to do to ensure your family has the rights you deserve. If you use sperm from a bank, then you don’t need to have paternal rights terminated whether you do at home or dr assisted inseminations.

ok after much research and reading this article it is still unclear to me if i can or cannot do at home insemination without a physician in the state of Arizona. Does someone know the answer?