Going Down (South) is a regular column about y’all being a gender neutral pronoun, how red states are actually more of a purplish color, boiled peanuts, and the trials and tribulations of being a rural homo — with an emphasis on the tribbing.

Header by Rosa Middleton

At a gathering of gay friends last spring, my iPod became the default white noise maker. After songs by Metric and Joan Jett that we all seemed to know by heart, Vickie Winans’ tambourine-slinging gospel anthem “Long As I Got King Jesus” began to play. In a matter of seconds, the white noise was no longer white, and the conversation changed from cute girls to Vickie’s wailing.

“Sarah, what the hell?” someone said. “Why do you have this?”

I shrugged. This was a valid question that I couldn’t answer. I don’t really “have King Jesus” in my life (neither did the woman I was seeing at the time, a conservative Jew). I just knew that I liked the song. Not really sure how to explain myself, I clicked my iPod’s forward button until shuffle settled on a track by Frank Ocean or Le Tigre or Rufus Wainwright or someone more palpable to our queer ears.

But my foot kept tapping to Vickie.

***

My hometown’s population is just under 8,000. In that same town’s weekly newspaper, there are over 40 churches listed.

To put this into perspective: That is one pastor to every 170 residents (less if we were to include associate pastors, of which each church has between one and five). Whenever I’m in a college lecture and realize that the ratio of students to professors is 350 to one, I laugh to keep from crying. Whether I like it or not, I’m forced to acknowledge that there have been far more religious leaders in my life than there have been academics.

I have Georgia red clay stains on my heels from constantly being barefooted and outside. Yet there are less visible marks, tell-tale indicators of my upbringing, which come from being raised in the church. Even though I’m now nonreligious, I still subconsciously live by the Golden Rule; half of my favorite quotes are actually Bible verses, and I’m still trying to teach myself to say “goddamnit” without cringing over breaking one of the Ten Commandments.

When I say that I “grew up in the church,” I mean the Baptist church…which actually means the Southern Baptist church. And when I say, “the Southern Baptist church,” I actually mean Southern Baptist churches. My parents were notorious church hoppers, and they changed my family’s house of worship membership a minimum of two times a year (with every move, we inadvertently scandalized a new racially unmixed congregation with our strange little multiracial family).

For my parents, Christianity came with a high; a promise of redemption, transcendence, and the overwhelming visual of someone dying for our sins — one which was often depicted in stained glass windows of those clapboard buildings. When the ethereal high that came from a particular religious institution waned for them, we moved onto a shiny new one. While my time under each steeple was fleeting, I noticed that we lingered the longest in congregations with choirs. Not stoic Sistine Chapel choirs or TV show choirs which deceptively promise a spot for every socially disenfranchised youth, but choirs as in, you know, “I’m about to break a sweat right now in the name of the Father, Son, and Holy Ghost” gospel choirs.

Maybe my parents stayed in churches with choirs longer because gospel music echoed and reaffirmed a pulpit preacher’s alluring promises of Heaven, love, peace, and prosperity. But gospel music, when done well, is also entertaining. An eight-hour service on a Sunday morning goes by a heck of a lot faster when there is not only music but physical movement, a chance to stretch your legs, clap your hands, use up some restless energy.

Christianity justifiably gets a lot of hell from queer people, myself included. But I’m not really here to beat the “religion is hypocritical” dead-as-a-doornail horse today. Instead, I’d like to talk about the ways in which these small churches function as accidental safe havens for the scarlet-lettered, the eccentric, the musically talented, and the queer. For many, salvation doesn’t come in the form of Christ hanging on a cross, but a gospel choir and a piano accompanist who can keep up. Willie Nelson’s heroes might be cowboys, but mine are these working class men and women — more often than not, people of color — who have voices as big as their hearts. I’m as much of a fan of Adele’s blue-eyed belting as the next person, but let’s be forthright and honest here: There are ~17 members of the Ebenezer Baptist Church Choir right down the road who can do the same thing better and while wearing musty old robes in 105-degree weather.

This is not to say that Southern gospel is accepting of girl-on-girl action or even hetero promiscuity — it isn’t. However, choir culture is all about unity and — if you have some sort of musical talent or at least the patience to develop it — a choir between here and the Mississippi River is bound to take you in. This has less to do with gospel’s acceptance and so much more to do with its resourcefulness. These churches do not perpetuate Glee‘s hoity-toity acceptance, and they certainly do not have the Brooklyn Tabernacle Choir‘s budget. The ethos of Southern gospel is one that dates back to the postbellum South: You’ve got to do the best with what you’ve got. And sometimes, all you’ve got is century-old choir robes, a thirdhand bass guitar, and talent in unlikely places.

Gospel is velvet robes detailed in gold, swaying hips, sweat, and a tempo that can easily rival that of any Benny Benassi remix. It is perfectly fine to be aggressive or flamboyant, as long as your audience thinks you’re flaming in Jesus’ name (as opposed to that of the cute lady in the front pew). Gospel is performance art. Gospel is up for interpretation: What seems like the exorcising of personal demons in song and dance form might really be one’s only way of expressing desire in an otherwise intolerant culture. Gospel is a masquerade. Gospel is a survival strategy.

This sort of talent doesn’t always stay behind the pulpit, however. It goes on do big things. Perhaps this is why many of our allies, gay icons, and even queer family are Southern gospel choir alum: The church has not only taught them priceless lessons about turning the other cheek and Sarah’s impossible laughter. They are also well-versed in regional accounts of brutal racial and sexual inequality, and the personal empowerment that musical unity necessitates.

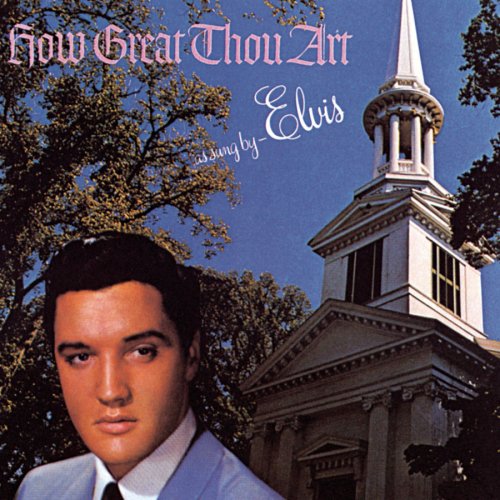

Tina Turner. James Brown. Little Richard. Britney. Elvis. Dolly. Beyoncé. Britney “bitch” Spears. In this series of posts on Autostraddle, Going Down (South) will explore these revolutionary voices in entertainment who are rooted in Southern gospel traditions, and how they continue to “perform” them in both their art and philanthropy.

See ya’ll next Wednesday. Like me, you might not have King Jesus, but these folks just might make you just wish you did.