The US Census only occurs every 10 years; respondents have only been able to report whether they’re living with a same-sex partner since 1990. Aside from the principle of the thing, that gay families can now confirm that they exist in much the same way straight ones can, it also means that there’s some interesting new data that for the first time, we have enough points to (sort of) analyze.

For instance, according to the Williams Institute at the University of California Los Angeles, the numbers of gay couples total has “jumped by half in the past decade, to 901,997.” (The Census doesn’t ask about sexual orientation, only about the partner you live with, so it can only measure same-sex couples as opposed to queer people.) Why the huge uptick? Assuming that the number of people who identify as not straight has stayed pretty constant — which is a tricky thing that depends on whether you count people who are out to themselves and to others — does that mean that suddenly everyone is a lot better at finding girlfriends? Is this about OKCupid?

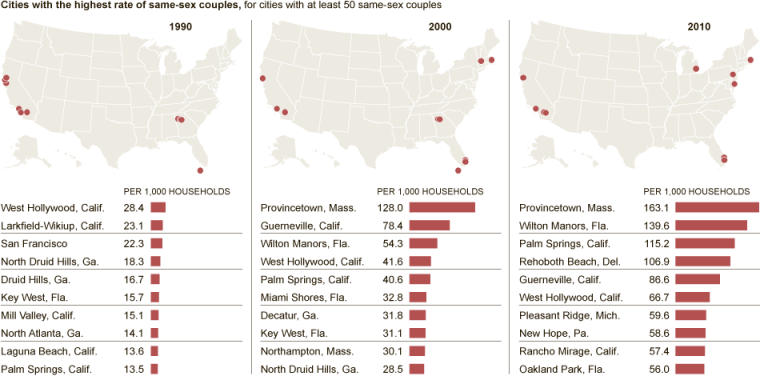

The Wall Street Journal has more surprising numbers; the number of reported gay couples has actually skyrocketed in the parts of the country that people generally expect to see them least, what the WSJ tactfully refers to as “farther away from the coasts.” “The number of self-identified gay couples rose by nearly 90% in Montana, Nevada and West Virginia, for instance, while California, New York and Washington, D.C., saw increases of 40% or less, according to [the Williams Institute’s Gary Gates’s] analysis of the data.” He also has some insight as to why this might be, barring the chance that everyone suddenly got a lot prettier and better at baking muffins:

The increase is too big to be explained by a sudden jump in coupling among gay people, said Gary Gates, a scholar at the Williams Institute at the University of California at Los Angeles, a think tank on sexual-orientation policy. Instead, he said, same-sex couples appear to be more willing to describe themselves as such, including in states farther away from the coasts.

Data from things like the Census is always interesting, because it’s self-reported; it ends up being less about the way things actually are in the world and more of an analysis of what people describe the world as being like, and why they choose to do it that way. If we go with Mr. Gates’ theory, the big takeaway is that we’re seeing a dramatic increase in gay people who are willing to self-identify as gay people in gay relationships, even on government documentation. A moving example is that of Michael Davis, who the NYT profiles as someone who might have answered the Census honestly in regards to their partner for the first time recently.

A decade is a long time in the gay community, and couples who were part of the pre-boomer generation said it had been all but impossible for them to come out. Michael Davis, 69, a retired intelligence officer who moved to Rehoboth in 2004, grew up in a small town in Wyoming in the 1950s, where homosexuality, in his words, did not exist.“When I was growing up, gay was a mood you were in,” he said, sitting at dinner with his partner, George Hooper, 64, a retired federal employee. For years he told people he was renting a room to Mr. Hooper. He could be fired for coming out in his job.

The census data showing huge increases of gay couples and families in places of the country that some think of only as areas where closeted gay cowboys are ultimately murdered and then mourned in really tearjerking scenes may also indicate more than just that people are more comfortable being honest there. The geographical surprises in the gay Census data may reveal a pattern of gay people and families moving to more rural and middle-of-the-country areas, away from the urban centers typically thought of as their arena. This seems to be partially because the baby boomers, one of the first generations where a large percentage of its gay people could live openly, are starting to retire. Either way, retirement or no, the message seems to be clear that places that were never considered safe or enjoyable to live in as an out gay person are suddenly okay, and not everyone actually wants to live in Park Slope.

Nona Willis Aronowitz at GOOD puts it like this:

There’s been some debate as to whether these numbers are accurate, as there’s no way of knowing whether or not people are “coming out” on Census applications. Still, this trend is good news for gays and lesbians. It means that the country is becoming more tolerant, and that the threat of violence and discrimination is slowly dissipating. A majority of Americansnow think same-sex couples should be accepted into society, and about half of them are in favor of gay marriage. As Slate points out, it may be more difficult for single LGBT people to live in more far-flung locales, because it’s harder to find a support system or a date, but same-sex couples are increasingly assimilating in all kinds of settings.

In short, in a long-term collective geographical sense, it’s getting better. Middle America is safer and more welcoming for gay people than ever before, which is good, because it’s most of America. And while any real scientist will tell you that 2-3 data points is a terrible basis for anything, so far the trend is upward as far as gay couples feeling more secure in being open about their families, and feeling good about living away from the traditional gay urban centers like New York and San Francisco. This is a good thing on its own, and also makes things better in turn; studies and polls have clearly demonstrated that knowing an out gay person in your real life, even if it’s just the grocery store cashier, correlates with being much, much more likely to support gay causes in general, and with that person then going forth to help make a generally more gay-friendly community. So it’s great news that smaller towns in Montana, Nevada, West Virginia and elsewhere now feel like safe places to live; it’s even better news that the people who live there are making them even safer. It looks like soon you won’t be able to throw a stick anywhere in America without hitting someone gay; and soon, maybe no one will want to.

Comments

“The Census doesn’t ask about sexual orientation, only about the partner you live with, so it can only measure same-sex couples as opposed to queer people.”

How do they deal with friends of the same sex who live together? Like, friends who are sharing an apartment? Do they specifically ask about “coupling”?

I’m just trying to picture what kind of questions they ask to get these data.

I don’t know how the American census works, but the Canadian census specifically asked the relation to your “Co-inhabitant”, so you can indicate that it is a romantic relationship instead of just being roommates.

It’s the same Down Under. There’s even a spot on the form to write down the details of anyone at your house on census night and specify their relationship to you. Someday I’ll write ‘random hookup’ ;)

In other geeky news… I <3 censuses. Or whatever the plural for a census is.

Censii?

They counted couples who answered the census form in a very particular way. If the first two names on the form were adults of the same sex, and they checked “married” or “domestic partner,” they were counted as partners.

It was a completely inaccurate way to count. For example, I share a house with a friend, but we put down married just so that we’d be counted. He’s Hispanic and I’m not, so I listed his name first so that we’d be counted as a Hispanic couple. The census was designed this way because the Bush administration really didn’t want to count gays at all.

The options for relationship on the 2010 Census are:

Husband or wife

Biological son or daughter

Adopted son or daughter

Stepson or stepdaughter

Brother or sister

Father or mother

Grandchild

Parent-in-law

Son-in-law or daughter-in-law

Other relative

Roomer or boarder

Housemate or roommate

Unmarried partner

Other non-relative

“Is this about OKCupid?”

Why, yes! Yes it is! :)

It’s partially due to greater awareness that you are allowed to indicate that your relationship with “Person 2” in your household is “husband or wife” or “unmarried partner.”

In the past there were far more LGB people who thought that since the federal government doesn’t recognize such relationships, you aren’t allowed to mark them as such.

And if you mark that “Person 2” is the same-sex as you, and describe them as your “husband or wife”, you may get a call from a Census worker asking if you made an error.

Based on well documented research over the past fifty years, including the use of psycho physiological measurements and pheromone response research, most authorities believe four to ten percent of the general population are homosexual, and there are degrees of heterosexuality and homosexuality. Recent research, funded by the Religious Right, using random demographic sampling, estimated the numbers of male homosexuals at one to two percent of the general population. A reported study by the census bureau is at best fraught with social and reporting level difficulties. Homosexuals and other minorities fear any “Big Brother” attempt to misuse information. Silent coding is well known both in the professional and “common sense” population of the U.S. (i.e., pin holes, special inks, etc.) This lower estimate of the numbers of homosexuals relied on randomized demographic designs (among males ages 20-40) and without taking into consideration any contribution to numbers of homosexuals related to overt social and physical trauma to women as in World War II. Such a sampling method is inadequate to estimate numbers of homosexuals, since unlike fifty years ago, many Gays ghettoize in large cities. Random demographic sampling has proven to be an inaccurate measure of structured populations, since the target group is not randomly distributed. A study using a similarly flawed technique estimated male homosexuals and bisexuals to comprise 3.7% of the general population. In the age of AIDS, being openly homosexual in any context, particularly before an unknown investigator, may produce research results based on personal, political, civil rights, or social agendas unrelated to sexual orientation. Since many homosexuals pass as heterosexuals and there are numerous sexual minorities who identify with the Gay community, this further confuses the difference between homosexuals and Gays. In the most tolerant of times, highly sophisticated and scientifically correct studies may underestimate the true numbers of sexual minorities in the general population. While the acceptance of an individual’s homosexuality appears to increase numbers of homosexuals during adolescence, numbers of homosexuals do not increase or decrease based on political and social activities or decriminalization of sexual acts between same-sexed persons.

Some have postulated that were homosexuals eliminated, human population would explode, causing widespread famine, pestilence, and suffering. Could Jung be right that homosexuality is a natural means of population control?

The information gathered does not appear to be a sound basis for a conclusion on the numbers of same-sexed “partners” in the general population. Particularly among women, having a female in the same house (i.e., sister, cousin, friend, etc.) to help with rent and child rearing in a platonic environment is relatively common.

Some doctor you are. You didn’t even look at the census form. And the study was done by the Williams Institute using census data. Did you even bother to look at their methodology? Did you even read the article completely?

Here, I’ll just copy my post from above, and then STAR the ones that counted as same-sex partners.

The options for relationship on the 2010 Census are:

***Husband or wife

Biological son or daughter

Adopted son or daughter

Stepson or stepdaughter

Brother or sister

Father or mother

Grandchild

Parent-in-law

Son-in-law or daughter-in-law

Other relative

Roomer or boarder

Housemate or roommate

***Unmarried partner

Other non-relative

‘ when I was growing up homesexuality was unheard of, gay was just a mood you were in’

No. People weren’t talking about it, they were doing it.

I think everyone’s experience is valid- this person grew up in the 40s and 50s and their perspective is important.

Sort of related, I read an article recently about the effect of gentrification on previously lgbt communities, its worth a read.

http://jpe.sagepub.com/content/31/1/6.abstract

The Demise of Queer Space? Resurgent Gentrification and the Assimilation of LGBT Neighborhoods

[…] culture screams Aquarius as emotional bonding is optional, not required. While looking for statistics on homosexuality over time, most of the data I found regarded approval or disapproval of various gender […]