It starts on October 2011. Egyptian blogger Alia Magda Elmahdy pohsts a photo of herself nude, along with a barrage of nude artwork and a message:

“Put on trial the artists’ models who posed nude for art schools until the early 70s, hide the art books and destroy the nude statues of antiquity, then undress and stand before a mirror and burn your bodies that you despise to forever rid yourselves of your sexual hangups before you direct your humiliation and chauvinism and dare to try to deny me my freedom UPof expression.”

At the time, street harassment was at a fever pitch, the military was forcing “virginity tests” on female dissidents, and there was no organizing around it.

What she did was comparable to the actions of Mohamed Bouazizi, the man whose self-immolation in Tunisia a year earlier started Arab Spring. Both used their bodies to shock society out of complacency and towards change. After Elmahdy’s statement, Egyptians began holding rallies against sexual violence, and demanding greater accountability. Virginity tests are now over.

However, while Bouazizi has been lionized across the Muslim and Arab world, Elmahdy was vilified (even by liberal secularists), received death threats, and was forced to leave the country. Egypt still has a long way to go with women’s rights.

Let me be frank: I’m a first generation Egyptian-American. My entire extended family lives in Egypt, including aunts, cousins, nieces, and in-laws. The issue of how women in Egypt are treated is a very personal one. Because of this, I supported Aliaa Elmahdy, and hated the craven way Egyptian liberals disavowed her in a cheap bid for votes. I may never live to see her get her due in Egypt, and that’s shameful.

The following year, she joined Femen, a Ukraine-based feminist organization, which specializes in “sextremism” as a means of political action. And, earlier this year, Amina Tyler, a Femen activist in Tunisia, posted a nude photo of herself online, with the message “My body belongs to me, and is not a source of anyone’s honor,” on her chest.

There’s been growing anxiety about the rise of (often violent) jihadism in Tunisia, as well as the increasing censorship of the Islamist government. Like Elmahdy, Tyler also received death threats, while a leading cleric called for her to be flogged and stoned.

A solidarity protest was called for April 4. Femen declared it Topless Jihad Day. Activists posted topless pictures of themselves from around the world to Femen’s facebook, and held topless rallies across Europe.

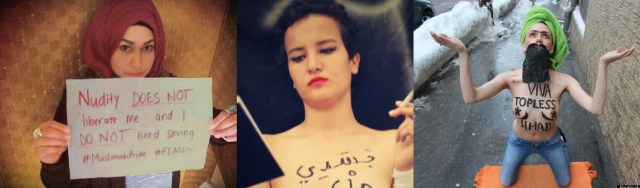

In response to Femen, Muslim women created a Facebook page called Muslimah Pride Day, and Muslim women sent pictures of themselves holding up index cards with a simple message.

“Femen does not represent me. I don’t need liberating.”

The page was covered by al Jazeera. Pamela Geller denounced it. And it was supported by countless Muslims, including many queer and progressive Muslims.

Including me.

Unpacking this issue relies on understanding one thing: Muslims are not monolithic. Muslims in the West (Europe, Canada, America) face a different set of challenges than those in the Middle East. And hence, they’re going to react differently to those circumstances. You know, just like everyone else.

In the West, neither Muslim nor non-Muslim women would face what Amina Tyler has. Nudity is, at most, considered a misdemeanor.

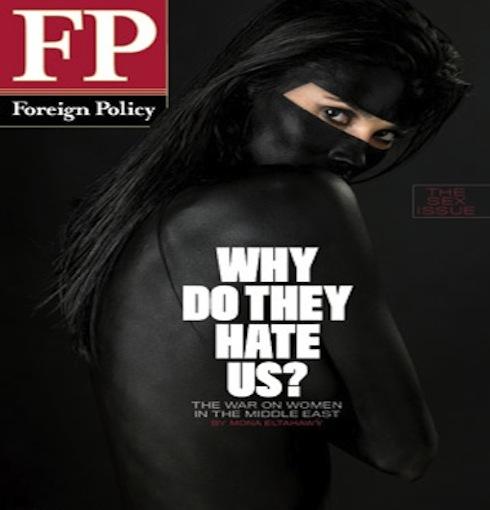

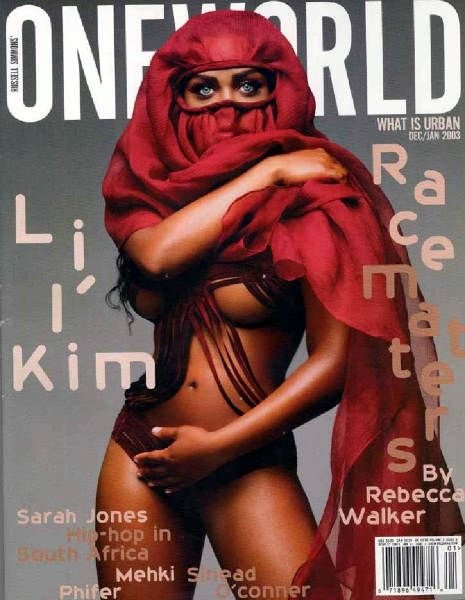

However, there’s also a strain of Western culture which sexualizes Islam and Muslim women. It dates back centuries, with exotic (and often fictional) accounts of the ‘sensuous Orient’.

In modern times, it revolves around the Muslim clothing, specifically, the hijab, nikab and burqa. Wearing any exposes one to harassment, even by law enforcement. Bans on burqas and hijabs have been proposed – and enacted – by Western and Western backed governments in the Middle East. And where there aren’t laws, there’s culture. The “naked burqa” trope (where traditionally Muslim women’s clothing is sexualized), is very

very,

very,

very,

common in the West.

And you can add Femen’s recent topless activism to that list. Context matters. You can’t disconnect actions from the longstanding cultural environment it came from. When Elmahdy and Tyler went naked, they were protesting specific groups dictating policy in their home countries. Activists in the West don’t have that context. Railing against Islamists here means attacking an immigrant group while reinforcing centuries’ old prejudices. And when you use Islamic symbols as part of your protest art, you put them out of reach for non-traditional Muslims.

The adoption of Islamic symbols in non-traditional contexts is an integral part of queer Muslim activism. Last year, I painted a crescent moon on a rainbow flag: a way of asserting both my faith and queerness. However, as proud as I am of that flag, I’m reluctant to bring it in public anymore. I’m worried it would be too associated with Femen. That’s what happens when your activism gets co-opted: you lose a means of expressing yourself.

And it’s not just queer Muslims. Femen’s activism fails to understand Western Muslims as distinct from their Middle Eastern counterparts. And the result is that Western Muslim women found themselves silenced. Muslimah Pride was a means of re-asserting that voice, if only in a cursory way.

Yet, for all of my vitriol at Femen, my initial enthusiasm for Muslimah Pride has faded.

Muslimah Pride was a Western Muslim women response to a Western protest. Fair enough, but their back and forth with Femen offered, at best, a cursory mention of the circumstances that led Elmahdy and Tyler to do what they did. It’s wrong to imply that Alia Elmahdy somehow went wrong by joining Femen. Femen’s tactics are absolutely necessary in the Middle East, and its support there is growing

And no, I don’t need liberating. But Amina Tyler does. She’s currently begging for political asylum, and worried about her safety. What is Muslimah Pride doing to organize on her behalf? What Muslim organization is? If Muslims can’t protect one of their own, how can we have indignant pride?

The sad truth is that the people sidelined are the ones putting their bodies, and lives, on the line. I’d hoped the Arab Spring would bring more attention to Middle Eastern voices. Instead, Western voices have appropriated that identity as their own, and continued to ignore them. Elmahdy’s blog is still active, and it’s amazing trove of information and artwork. And no one, either in the press or the dozens of opinion pieces about this, has linked to it.

Well I am, as well as the Facebook page for Femen Egypt & Femen Tunisia. Go to these sites and hear the voices of these women for yourself.

After all, it’s what we’re fighting for.

UPDATE: At the time this article was written, Amina Tyler was being forcibly held by members of her family, in relation to her pictures. Since then, she has managed to escape, and is, by all accounts, safe. You can hear about her ordeal here.

About the author: Miriam lives and works in Texas, and currently blogs for I Am Not Haraam. She’s not very good with bios.