Dapper Became Me

by Blakeley Calhoun of Qwear

The origins of dapper style are so scattered that no one person could ever definitively conclude that one race or class or culture started it all. Before the late 20th century, there was an unwillingness of scholars to give credit to non-white and/or non-heterosexual persons for their work (for example, in the age of Motown white musicians would take songs that were written by black musicians and groups and claim them as their own). As a result, movements were, and still are, associated with and credited to a “white male elite.” The history of fashion, particularly dapper fashion, reflects this trend. It is unfortunate that many people only associate dapperness with maleness, richness and whiteness. History tells us that non-heterosexual and non-white men and women of all socioeconomic statuses have been dressing dapper for just as long, if not longer, as the “white male elite.” The mission of this piece is to problematize the association of dapperness with the cisgendered white male elite.

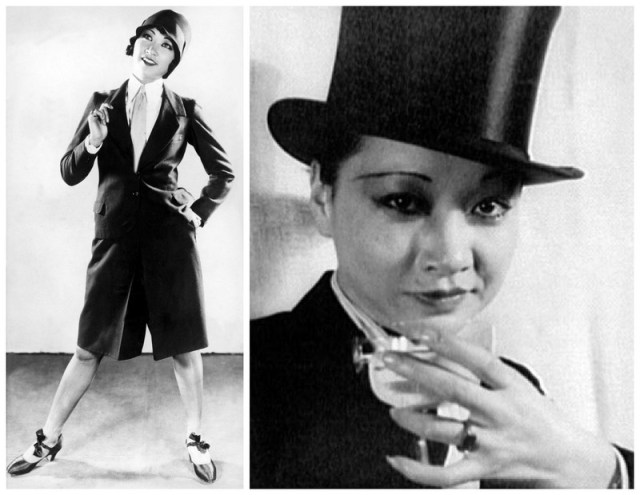

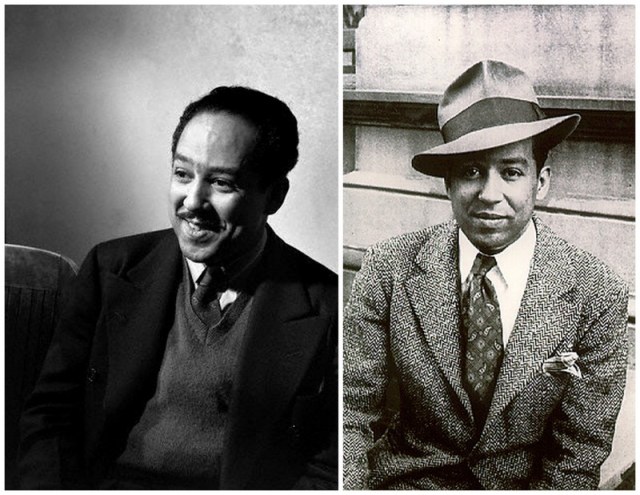

Let’s start with some non-stereotypically dapper people. Elements of dapper style can be found within the Harlem Renaissance (1920s). For example, Gladys Bentley was a prominent singer of the Harlem Renaissance. Bentley performed in various nightclubs around Harlem. She was known for her many girlfriends and her dapper attire. Anna May Wong is considered to be the first Chinese-American movie star. She was no stranger to dapper style. And of course, , Langston Hughes..

When I was researching for this post, I Googled, “men of the 1920s” for inspiration. I was almost 5 pages in before I saw a person of color. The problem with associating dapperness with a white male elite is that it glosses over decades and decades of history. A history that takes some work to uncover. Dapper style should not be tied to whiteness. Dapper style should not be tied to richness. Dapper style should not be tied to maleness. By stereotyping dress, we perpetuate the erasure of the contributions of queer people, people of color, and other minorities to fashion. When I dress dapper, I don’t think that I am reinterpreting a particular style. If anything, I am going against societal expectations for how a woman should dress. However, reinterpreting suggests that I am taking a style that is foreign to my culture and incorporating it into my everyday wear, which is simply not true.

My entire life I have been wearing things that I was “not supposed to wear.” I wore Vans and tennis shoes in elementary school. The former created quite the stir. At the time, no other Black 10-year-olds in my school (there were only about 5 of us) dared to dabble in the “I don’t know how to ride a skateboard but I watch the X Games” skater style that was gaining popularity with the other kids at school. I didn’t care. I wanted to fit in, so I bought some Vans. I was that kid. I didn’t want to stand out so I made damn sure that I stayed on top of a trend. When I wasn’t wearing Vans, I was wearing tennis shoes. I never wore women’s shoes growing up. I liked the colors on the men’s shoes more than the pink and purple varieties I was supposed to like. Soon I was in high school and people were growing up style wise – some girls got push-up bras, most started to wear make-up. My style stayed the same- t-shirts, jeans, and tennis shoes. When I was feeling particularly fancy I threw on a cardigan.

The acceptability of my tomboy phase began to disappear. I was getting too old, it was time to femme up. But I fought back. My mom would buy me low-cut shirts – to me low cut was anything more than one inch below the neck – that I stubbornly safety-pinned shut. I didn’t want to show my body; I wasn’t ready for the male gaze that my body invited. Dapper style gave me an out.

It wasn’t until recently, some time in the past two years, that I found my style niche. In 2011, I began my first year in college at an institution that values bow ties over most things. We dress up for football games and everyone owns a blue blazer and boat shoes. Moreover, aesthetics are just as important as your GPA here. My t-shirts and cardigans were not going to make the cut. I took the number seven bus to Belk, bought some button downs, a pair of khakis and tie. I dressed out of desperation. I wore bow ties and button downs because they look nice, but more importantly because I wanted everyone to know that I wasn’t straight (baby gay seeking other baby gays). It was a big turning point in my life. I found comfort in my dapperness. I’m not sure if my new clothes made me feel empowered, but for the first time in my life, I did not feel disempowered. Dapper became me.

My ancestors were neither white nor rich. They did not attend Ivy League schools. In fact, very few of them were “educated” in formal institutions. But they didn’t wear sweat suits to work; they wore suits. They were dapper in every sense of the word. And so I, their descendants, should be able to dress in any manner I choose and not have it reflect a white tradition of wealth and masculinity. Dapperness does not belong to any one culture. I shouldn’t have to “reclaim” my dapper style. It was all of ours to begin with.

About Blakeley Calhoun: I’m a 19 year old college student that is obsessed with fashion, Florence Welch, and bow ties. I love my dog more than I love most people. I talk to my dog more than I talk to most people. I watch the Golden Girls on Friday nights (well every night but Friday in particular). Paris is Burning is the best documentary ever created. I answer plus-size questions for qwear.tumblr.com. I am currently the co-president of the Queer Student Union at my university. I like nautical themed things but I’m not sure why. In addition, one day I hope to be a professor. I have a hard time not using ‘I’ statements. None of the previous sentences seem to be connected in any way and that’s essentially the best way to describe me-lots of random tidbits trapped on one plus size queer.”

Comments

Omg, that pink and orange suit. I need that. Either on my body or on someone’s body who wants to make out with me. Either way I’d be happy. Also I like the tie necklace combo. I’m going to give it a try.

i wore a little necklace under a collared shirt the other day and really liked the effect, i’m going try over a tie next.

You two are so fancy, I just want to drink mimosas with you.

I have a pocket watch necklace that I sometimes wear over a tie and I look pretty awesome if I do say so myself (and I do say so, often). There may be a rabbit on the watch and I may or may not run around declaring myself late a lot.

for a very important date?!

A gentlequeer is NEVER late for a date ;)

I love both of these pieces so much. This is a topic near and dear to my heart, and you both spoke to a lot of my feelings about dapper/dandy aesthetic while also giving me new insights and perspectives on it. So thank you.

That butch please article felt nonsensical & whiny to me.

I very much love this article, it seems to be more fact based & inclusive of the various motivations for style & the responses to it.

Hey now, This article added to the conversation on dapper without invalidating somebody else’s, can’t we do that, too?

But that’s my opinion, those are my thoughts on that article. That butch please article was very invalidating to people who like to dress dapper. It basically said that dressing dapper is a wealthy white male invention & that dressing dapper is a way of emulating that identity. That hypothesis is wrong & say so is not a personal attack.

Whiny might be a bit harsh and personal. But otherwise I agree.

An “opinion” can’t be invalidated if it’s presented as fact while ignoring the history behind a certain situation. Facts and history exist and we need to recognize that instead of just saying something like “dapper is emulating rich white straight dudes” while ignoring the existence of something like the Harlem Renaissance and, I don’t know, motherfucking LANGSTON HUGHES, who was clearly not a straight rich white dude and doesn’t seem the type to be emulating straight rich white dudes.

In conclusion, I like sources and stuff. And we don’t have to call people whiny, but we can say that the history is illogical and the article doesn’t make sense if the history is illogical or ignored and the article doesn’t make sense. And I think this is what “Yea” is saying, but I’m trying to present it in a nicer way while also exhorting people to back up their ideas with facts.

Thank you. I guess the whiny comment can be interpreted as a personal attack & mean but that honestly isn’t my intent. The tone of the article seemed whiny to me. It seemed like the author of that article became disenchanted with the dapper style because it is trending & everyone ‘is doing it’ so they were inventing reasons to abandon it. The beginning of that article was essentially them saying “I’m over it”. I follow their tumblr & that was a post they made on tumblr before that article was published on AS. Anyway I’m sorry if what I said sounds mean.

These are all fair points, I really only had issue with said whiny comment, and jumped on my feelings train a bit quickly, my bad

By the way, comment exchanges like this on Autostraddle are why I still have hope for other comment communities to add things of value to the world!

Thank you thank you THANK YOU for the various citations and historical facts (as well as opinion) in this article.

also thank you for all the amazing fashion photos because OMG inspiration.

I don’t let anyone give me shit for dressing how I want. Ironically, I rarely get any trouble while wearing a bow tie or tie, but I was wearing a very casual summer outfit (jeans, short sleeved buttoned shirt, and some bright sneakers) while walking in downtown St. Paul during lunch hour. A guy smiled at me from across the street (a kind of quizzical smile) and I smiled back, and when the light turned to walk we met in the middle of the street and he asked me if I liked dressing up like that. I was like…’yes’ even though I have no idea what that meant.

#dapspiration

Both of these pieces are really interesting and important, thank you

Love how you can have both on AS amazing articles that include (1) diverse perspectives and facts and also (2) eyecandy :)

This is a great article, i love all the history and pictures you included! Now i am finding you to follow on tumblr.

I remember feeling unsettled about the original article’s position on dapper as a rich white man’s thing. Thanks for this history – this is how I was taught the origin of dapper by my elders.

If you’re referencing my, my blog is queerplusfashion.tumblr.com

I love your blog!

Thanks!

dapperQ loves Blake too – stylish AND smart. Always a pleasure and one of our favorites. If you want more Blake eye candy, take a look at a week’s worth of Blake’s dapper style here:

http://www.dapperq.com/2013/01/seven-days-of-dapper-blake-calhoun/

You might want to look at Laura Doan’s book Fashioning Sapphism, about the emergence of public lesbian identity and style in the interwar period. It’s a great study and has lots of fantastic pictures.

EVERYONE IS JUST UGH, SO GOOD-LOOKING!

This article and the Butch Please article about the dapper gave me pause on how I interpret my own tomboyfemme dapper style. I was aware of the black dandies but I was engulfed in such whiteness that is Penn State I would forget sometimes and use it as an armor to decrease the micro-agressions my brickhouse of a body would “invite.” Then I moved back to DC and had to deal with the class implications of dress in a more diverse community but it all still just felt wrong on the assumptions I and other have made in regards to dress and especially being dandy. I may not rock bowties like I used to but damn I love a vest and some suspenders!

Now that I just. don’t. care. anymore, I am more free and respect the style choices that other queer-identified people wear. It’s beautiful and UGH, EVERYONE IS JUST SO GOOD-LOOKING!

yes yes THIS thank you

“because it is a form of in-your-face protest”

“I shouldn’t have to “reclaim” my dapper style.”

exactly this.

as i also commented in reply to that butch please post,

to me personally, dapper is a way of expressing myself that reflects several parts of my identity. there is no emulation involved, it IS my identity. i associate dapper with academia, with being queer and doing masculinity in a non-normative way. of course, this is my interpretation, what i express with it.

there are so many ways of doing dapper, so many interpretations that are all valid and real, and i really appreciate that these two pieces acknowledge/emphasize that.

ps: blake, i like your style a lot! your outfits on qwear are always so perfect

Thanks! You’re too kind.

I have a couple questions:

1. What are we considering dapper? I mostly associate the word dapper (when used in queer spaces) to refer to bowties and brightly colored clothing.

2. Why is Langston Hughes being considered dapper? Wearing suits when being professionally photographed was expected of professional men such as himself. The feeling I always got from pictures of him was of a less kept more relaxed manner of dress. In non-professional pictures he’s often not wearing ties and is wearing plaid shirts with the top couple buttons undone.

My understanding of dapper/dandyism is to refer to things that qualify under a masculine style of dressing up, but with an edge or quirk of some sort. That can be a floral pocket square, that can be a bow tie, that can be a bright shirt, that could be a neat pair of socks, suspenders, anything.

I don’t think it has to be expensive but it does imply a certain flair and pride in one’s appearance while dressing up. I would appreciate other answers to this question too, anybody else? And just because someone is dapper sometimes doesn’t mean they are always as dressed up as possible, which leads me to question 2. In which case, I’m gonna say LOOK AT THAT STYLE. Look at the jaunty tilt of the hat, the mismatched but amazing patterns on the tie vs the suit (herringbone vs paisley) BUT FOR SERIOUS. Breaking so many typical fashion “rules” and looking great while doing it.

Also, honestly I don’t know as much about Hughes and the Harlem Renaissance as I’d like to, but I know the era was very tied into dandyism. I wouldn’t be surprised if Monica Miller’s book addresses Hughes and the Harlem Renaissance in detail, so that might be a place to find more info.

To all of the everything in this article ever, this is 100 percent win.

Also, to Ariel Speedwagon (the handsome devil in the first solo photo) and the DapperQ production team –

You taught me how to tie my bow tie. I keep your video pulled up in my Vimeo app in case I ever need a reminder. Thank you for that. You helped me realize my bow tie dreams, and thus my interpretation of dapper.

*Apologies for previous mess of a post- my laptop is having some sort of emotional problems right now and acts out occasionally*

Okay you guys, crowd source information time. I’m going bow-tie shopping tomorrow. I want to pick something good since it’s a thirtieth birthday present for a friend.

My gut is that the proper-tie-them-yourself kind is the only way to go and those clippy ones are a cop out. Yay or nay?

Also, Ali can you link me that vid please?

Friends don’t buy friends pre-tied bow ties.

Second Blake’s opinion! Here’s the vid: http://vimeo.com/27054705

Shirley I just have to say that I get pretty much all my bowties from thetiebar.com which is amazing and also inexpensive (all ties $15, unless they’re part of the “tie the knot” collection which are $25, proceeds going to marriage equality organizations).

So if you do want to peruse a grandiose variety of ties on the internet, it’s a great choice and the quality is comparable to slightly more expensive ties you’d get in the store, although clearly they don’t look like $300 ties.

The way I talk about The Tie Bar you’d think they pay me, but I just like their bow ties.

Awesome, thanks for the advice! I’m glad my gut was right on the whole pre-tied thing. They just remind me of those awful rental tuxes teenage boys wear to take you to dances *shudder* so. much. cheap. fabric. eugh.

Marika, you should totally work on them paying you, at least payment in ties, cos that was an awesome pitch.

But yeah, this is why I love AS. My upbringing left me so ill-equipped for actual situations I’m likely to encounter in my big queer day to day. And yet, so much useless information. A friend of mine was going to a family wedding recently and was a bit anxious about the whole wearing a hat thing and I suddenly piped up with “Don’t worry, traditionally the mother of the bride takes her hat off at the beginning of the meal and all the other women can do so after that. If it’s a fascinator, those generally stay on all day.” Why do I even know this? Or how to word formal thank you notes? Or what type of dress to wear to a semi-formal/black tie/white tie dress code? Have I blacked out some time spent in finishing school??

Shirley, oh my gosh, I want you to be my fancy person advisor. I only know little things like what tie knots are most formal, match your shoes and belt, etc (it works because I have one nice belt and one nice pair of shoes so it’s ALWAYS BLACK, that’s easy) but I need alllll the other stuff.

*squee – somebody thinks of me as an actual grown up!!!*

Ahem.. I mean…

Thank you for your kind words. I would be delighted advise you on matters relating to fanciness and all other etiquette based frivolities.

Warmest Regards,

Shirley S

This was a really cool article! I was aware that dapper has a long (and very good-looking) history of non-whiteness, but I do think its drift from its common image of ‘powerful, and therefore elegant, older white man’ has a caveat when it comes to class.

I’m not at all saying that this makes dapper style inherently wrong, but I think the central idea of dapper is a ‘polished’ aesthetic, a sense of discrete luxury (this shirt is perfectly cut, my shoes are of great quality, my tie is silky, etc.) that is made to appear distinct form the rest, to have the quality (and therefore costliness) of garments speak in favour of your personal refinement.

I think this idea of spotless, luxurious refinement (very tied to wealth and class aspirations) is still at the heart of this style, even when it is created affordably (and sustainably, which is wonderful!) today, because non-high-end versions still aim to create the same feeling of an elegance suggestive of material ease.

When we recall the uniform day attire of many of our parents, grandparents, and sometimes ourselves, I think we might be touching on some kind of ‘second tradition’ of dapper, one usually cheaply made and unadorned, that served towards the working class a function of spotlessness rather than grace (even though that still does carry connotations of social lift).

I understand that people are proud to honour those that came before them with a dapper style that is reminiscent of this. I do, however, think that Kade’s reminder of the class connotations of emulating a certain nostalgic, once-anointed sartorial elegance, remains justified.

Agreed.

This is a worthwhile conversation.

With that said, I don’t really understand the idea of “class connotations”. Is it bad to reflect a particular class (namely, the upper class)? What are we aiming for? Just above lower class, but definitely not upper class? Middle class? None of the above? There seems to be some hesitation to appearing to look upper class, whatever looking upper class looks like.

Every action within our day is a class marker. I go to Food Lion instead of Whole Foods. I thrift instead of shopping at department stores. I can afford to not work and focus full time on my studies. I drive a car that my parents put gas in. I can afford to eat out every once in a while. And so on and so on. My main point is that there is no avoiding giving off a “class connotation” (whether it is intentional or not intentional). If looking one’s best means looking upper class, what’s wrong with that?

On a side note, how we look and the clothes we wear are not always indicative of class (As of today I dress what some label “upper class fancy/dapper/dandy” and I am an unemployed student. Thus my class is for sure not upper class). Associating an image with a particular class is problematic in my eyes.

But then again, what do I know?

The class thing is further complicated by the fact that really upper class people will dress down, since nothing says “new money” like dressing up. So you have the lower class people dressing up to look upper class and the upper class people dressing down to look lower class and the middle class people dressing up, but worrying that people might think they’re upper class, although not wanting to look like they’re lower class.

It’s all a bit tiresome really.

Live and let live.

Yes to this. So what if you look upper class. So what if you want to look/be upper class. Should we only dress in rags if we’re not white, male and wealthy? Should we dress in semi rags of we’re only one of those things?

I think you’re right, there’s no avoiding indicators of class.

Here’s where I think a complex can happen in this instance, though:

A style (in dress or otherwise) is born of its declared distance from the mass, that is perceived as being less enlightened than the new group.

When the style’s components include projecting an image of material ease (through the various cues I was talking about above), then the mass is those perceived not to have that material ease. In other terms, dapper style is part of a set of styles whose founding distance is an upper-class/mass one.

Historically, its main axis as a distinctive style is a classist one, and probably not of the nicest sort (‘I am part of the elegant, for I am part of the wealthy’). Today, though, as you make it clear, class indicators are blurred and the wearers of the style vary greatly in their backgrounds and class aspirations.

I just wanted to point out that dapper style still has connotations of upper-class grace and impeccability (and like all styles, it exists versus something else) today, and part of the attraction of that style is its heirloom positive social grade marker (whose opposites are working-class markers, and it’s because that struggle where the upper-class gains by outshining the other is still actual that a problem can arise). It’s probably not fortuitous if some people ‘look their best [while] looking upper-class’. I argue that it’s not just a dated class/appearance association being thrown at the wearer, it’s also the wearer projecting a specific appearance that appeals partly because its class association is positive and approved of.

I am certainly not saying that people should not dress dapper, nor am I saying that being fancy is bad. I just wanted to suggest that reflections on the subject are important and actual for modern dappers (possibly especially queer dappers) who appreciate this aesthetic, because the ‘style/mass’ tension of this style is one that is part of a societal problem.

(Basically I just think that knowledge and conscience are good.)

Here’s the thing, though. As an African-American, I know that my ancestors were not brought to this country wearing what slave owners wore. So,*most* of the clothing I wear is born out of some classism, racism, etc. Even the language I speak is not that of my ancestors.

Having knowledge and conscience are good, but Kade’s piece ignored many rich diverse experiences, histories, perspectives, and contributions from minority groups that define dapper – and these contributions are just as important to recognize and celebrate as the “white male” contribution. Knowledge and conscience of these experiences are needed as well, and we hoped to have provided that in these two additional perspectives (dapperQ’s and Blake’s) without denying Kade’s experience.

Further, for some, assimilation to an oppressed culture is a *daily* (conscious!) reality for some of us – this is not something that we need to be “schooled” in and it may come off as elitist in and of itself to assume that “the poor” and QPOCs need to be “educated” by wealthy and middle class folks about why it is we do what we do. I live in a White world and I am quite aware of this.

I think the richness of what queers, women, POCs, and individuals belonging to other SESs have to contribute to the dapper history is important because it shows the power to reclaim and redefine. Sometimes doing this alone is an act of recognizing the power dynamics and yet defying them. But, that’s just my own personal opinion and not that of the entire dapperQ team.

Sorry, I meant to write, “assimilation to an oppressive culture” not “oppressed culture.” I also don’t normally look like a Muppet. But, I sorta feel like one today ;)

There is nothing wrong with being a Muppet. I aspire to be Miss Piggy, that pig can kick ass.

Hi Anita,

Thanks a lot for your comment, it’s really rich and I’ve been thinking about it for hours now.

First off, I’m really sorry about the tone of my comments. I realize now it seems like I assume every dapper is ignorant of what I’m saying nor gives it any thought, and that’s extremely offensive when you’re a reader of colour and/or of lower SES and you’re confronted daily to the racism and classism in the everyday things you do.

I’m genuinely sorry about this.

I also see now, after rereading, that the tone of the article doesn’t make light (like I originally felt it did) of the historical classism in the dapper costume. I sincerely, upon first reading, found it refreshing to see its ongoing nonwhite (and non-male) history recognized, but I hadn’t realized that it also said something like ‘now that you don’t have to be rich to dress like this, where do we go from here?’

PS: I originally found inspiration for my comments in the history (and critique) of the ‘société des ambianceurs et des personnes élégantes’ (SAPE), a famous style movement in post-independence Congo (similar to another in the Ivory Coast) that appeared first as a declared stylistic reproduction of the dress of the European nineteeth-century, and that over the course of the eighties, began a daring approach to colour in formal elegant dress, breaking off with Western conceptions and evolving into a distinctly Congolese interpretation not unlike the fifth picture.

The movement can (and should) now be considered as an authentic nonwhite and non-western tradition of dapper that still exists today (some TV shows in Congo are exclusively devoted to the style), but come under fire by many Congolese now [source: http://www.congopage.com/La-Sapologie-une-doctrine-honteuse%5D for its consumerism and materialism because the movement is attached to designer clothing, held outfit competitions, etc.

(It’s still the same poster, ‘hide’, Autostraddle only lets me reply logged in now, sorry about the confusion!)

“Class connotations” means dapper looking clothes are expensive and I can’t afford to look like that. :) It also means that nobody in my family has ever been able to dress like that on a daily basis and that if I see someone “dapper looking”, I will automatically assume they have and grew up having more money than I do / did. Which will make me nervous (about whether they read me as a worthless working class immigrant fraud?) and probably a little embarrassed of my uncool, unexpensive clothes which I bought (probably many years ago) mainly because they were sturdy and sort of “nice” (I buy clothes if I like their prints? see, this sounds incredibly shallow compared to people who go on about how fashion is an extension of themselves etc etc).

I realise that being an immigrant plays a huge part in it, but queer dapper spaces sort of read like “spaces full of middle class western queers with whom I won’t be able to relate / who won’t like me”. Especially if it’s spaces in which everyone takes dapperness really seriously – if this were just people going, these expensive clothes are nice so I’m going to buy / wear them, it would be different – but it’s more like, these expensive clothes are a complex form of self-expression and they say so much about what a complex and radical individual I am – the implication that my boring clothes make me uncomplex and unradical is always there, hovering the background.

Andrea, I see where you’re coming from and don’t want to invalidate that by any means. I just wanted to add, however, that like Blake, I buy my clothes veryyyy on sale or at thrift shops because I’m a student without a lot of money to spare. I wear a pair of sneakers until they literally fall apart, I have one pair of dress shoes (which I will probably wear until they fall apart too). And the shirt I’m currently wearing looks expensive, but I believe it was $6 secondhand. I buy jeans from the Aeropostale men’s dept, usually, and they are almost always under $20 new. And when they inevitably get holes because they are from Aeropostale, I patch them with iron on patches and carry on.

But it is COMPLETELY OKAY to buy sturdy and kind of nice clothes. In fact, it’s what I do, just my sturdy and kind of nice clothes tend to be from the men’s dept (they fit me better and tend to be more comfortable) try to have some flair, and are accentuated by the occasional tie or bow tie (which is where I tend to splurge a LITTLE by getting a couple at $15 each every so often).

I love dapper style guides but I can’t afford the new J. Crew summer line either. :/

and I really, really, really hope people aren’t judging you for your clothes. Some people are really into fashion. Some people aren’t. That’s not a big deal. You do you! Most of my favorite people aren’t really into clothes and you are absolutely not obligated to say ‘this shirt is an extension of my personality’ instead of ‘this shirt was on sale and I like it.’

I know, I know – class markers are quite complex, and there are a lot of different ways of doing dapper, and even if your clothes look middle class, there are a lot of things that can give you away if you’re not, e.g. accent, general demeanour etc. But there’s buying clothes from thrift stores and then there is what this article calls looking for “one-of-a-kind vintage pieces”, and the difference between the two is typically the class of the person buying the clothes, so clothes are tied up with class in more ways than people think.

I don’t want people to stop wearing the clothes they enjoy wearing, obvious – it’s just that while feminist and queer communities / spaces do a pretty good job at criticizing more feminine styles (which, of course, can be just as middle upper class looking), in many ways it feels like people think dapper is completely above any kind of criticism because it’s so queer.

I agree. I feel really weird when people in queer communities spend a lot of time criticizing feminine style and I am uncomfortable with the idea that queers all have to dress androgynously/dapper/dandy/masculineISH to be identified/be a real queer/whatever.

and yes, clothes are very much tied into class and I really hope that my style doesn’t alienate anyone (back to your previous comment) because that’s absolutely not the intent. But also I don’t live in a city with a huge queer community and so it’s unlikely that I’m somewhere with a gaggle of queers all wearing bowties (Unless it’s A Camp and I teach my cabin to tie bowties for giggles) so I guess it’s hard for me to see the perspective that when there’s a group of people dressing dapper/fancy, it can be intimidating and uncomfortable for others who aren’t part of that aesthetic, but I think I can see how that would happen. Thank you for sharing your perspective!

@Marina

I get how this might seem strange without the experience of significant numbers of dapper looking people all in one place, but as several people have already pointed out, dapper is pretty prevalent in academia, and I guess coupled with that environment, in which I often end up sticking out like a sore thumb anyway, it intensifies feelings of inadequacy / alientation.

Also, (I just thought of this so please bear with me), class is relative. For example, if we decide that bow ties are classist and are intended to push away the less fortunate (I know that’s not what you’re saying), then we stop wearing bow ties and start wearing ties. Then we find that ties are the top rung. So we stop wearing ties and start wearing necklaces. We discover that not everyone can afford necklaces and when we wear them they further perpetuate the class divide. So we stop wearing necklaces and blah blah blah.

If it’s not this, it’s that. If not that, then this. Wealth, class, and status are 100% relative.

Also, the dapper class indicators are “perceived”. I have never heard anyone describe their mode of dress as an instrument to distance them from another class of individuals. In my experience, all of those feelings of distancing are preconceived. For example, when x wears y, I feel like I don’t belong in x’s group. However, x never said that I don’t belong. That’s just how I feel. I feel this way not based off of x’s actions, but off of the history of what x is wearing.

So yea, that’s just what I think.

Katharine Hepburn should be added to the style icon list in my opinion. That’s who I aspire to dress like.

Katharine Hepburn should be added to ALL the lists because that’s who I aspire to be.

Hopefully this isn’t too out of place, but I’m interested by the way dapper style is generally framed as being masculine and women who adopt it as being masculine as well.

I guess I’d argue that gender policing has long placed limitations on the kind of ways one can be a woman (forcing people into conventional femininity) and now thanks to feminism and gender activism there’s an expanded range of ways one can be a woman. A woman can be dapper without invoking masculinity in the same way that a woman can be good at science or being a business leader without invoking masculinity. Just because those things have been gendered as male doesn’t mean that femininity is not big enough to contain them without referring back to maleness.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m cool if people identify with masculinity, and I wouldn’t want to get in the way of that at all. However, it does surprise me wingtips, blazers and bow ties are accepted without much question as being inherently masculine in queer spaces. To someone who would gladly go all Marlene Dietrich on everybody’s asses but doesn’t identify as moc (or believe in the c really) it can seem like an alienating discourse.

Dizzy! Now I feel weird because I did use masculinity in my understanding of dapper dandyism, and that’s not true. I think the idea is that it involves clothes that have traditionally back in the day been gendered towards men but that absolutely doesn’t mean they’re masculine and I also like that dapper tends to include a flair that might be considered a little more feminine (floral prints, that pink suit, etc.) I’m sorry if I contributed to you feeling alienated and thank you for bringing it to my attention.

Marika! No need to apologise, please! Thank you for such a lovely and thoughtful response. It’s cool with me if masculinity is important to your understanding of dapper dandyism and it’s cool with me if it’s not as well. We only get one life and we all gotta be who we are.

I guess what I was trying to do (clumsily, because it’s such a complex topic to raise) is just suggest that it’s possible for a woman to dress, look or act that have traditionally been gendered masculine without herself identifying as masculine or being gendered as “masculine of centre”. Something I’ve observed around here is that there’s a tendency to assume that ties and pants = butch, masculine identity whereas dresses = femme, feminine identity. Sometimes it’s true yes but other times it’s not.

I’m also trying to argue that we can do and wear things that have historically been gendered male without referring back to maleness. Like womanhood in itself is big enough for bow ties and swagger and we can do that without calling ourselves masculine. Again, if a woman identifies with masculinity then I am super cool with that, it’s just that I think she doesn’t *have* to in order to do dapper. Again it’s complicated so I hope I’m getting the point across.

I’m not personally alienated by the post, in fact it’s a great post and I welcome its presence on Autostraddle. It’s more a broader discourse that assumes that if you dress a certain way and act a certain way then you MUST be masculine / feminine that I take issue with.

Dizzy, I do not think that you are out of place at all! dapperQ does have a more narrow, targeted focus and serves as a resource for masculine presenting gender-queers. The team submitted this within the context of our site’s mission and specifically in response to the “Butch Please” post.

However, as the only femme contributor at dapperQ, I can see how this conversation can be alienating. Yet, I also do not feel that dapperQ’s mission and advancing femme visibility have to be mutually exclusive. We are welcome to adding diverse perspectives to the discourse.

As we start to move beyond the gender binary, there have been some interesting debates brewing on dapperQ’s Facebook page. For example, menswear has been adopting more traditionally “feminine” touches, such as florals, metallics, strappy sandals, pastels, etc. When we featured some of these items and the above image of the tie/necklace combo, which was provided by The Test Shot, a project documenting transmasculine style, some of our readers said it was too “femme” and “flamboyant.” (We disagree with the general premise of such comments.) The Test Shot wrote a great response about feminine masculinity here: http://www.dapperq.com/2013/05/feminine-masculinity-an-oxymoron/

Additionally, while still keeping in line with our mission, in response to some of our readers feeling like they are somewhere between femme and moc, we introduced Tomboy Femme Fridays http://www.dapperq.com/tag/tomboy-femme/

dapperQ even paid tribute to some of our favorite feminine dappers here: http://www.dapperq.com/2012/08/our-favorite-images-of-gender-bending-femmes/

But, I would like to see a more comprehensive piece on femme dapper style for sure!

Anne, thanks so much for welcoming my comment on this post, I really appreciate it. I also really love the examples you’ve given of the way dapperQ is advancing femme visibility. I think that’s great. Something I’ve always enjoyed about DapperQ is that it shows a diversity of size and culture. It’s cool that there is an emphasis on gender diversity as well.

I guess what I was trying to say, albeit very clumsily, is that I think that it’s possible do dapper or wear things that have often been the province of men without necessarily being butch/masculine OR femme/feminine. I’m 100% supportive of butch/femme identification and I would hate for anyone to think otherwise. I just think it’s a shame that people assume that if a woman has short hair and rocks a suit and wingtips then she must be masculine. I mean, maybe she is. But maybe she’s just one of the many delightful flavours of womanhood and masculinity never enters into the equation.

It’s a complicated point so I hope it makes sense.

I get your point. I didn’t articulate mine as well as I had hoped. I see what you’re saying about clothing not always having to be labeled butch/masculine OR femme/feminine (identities rooted in the binary). This is the issue we came across with The Test Shot image of the tie/necklace combo, because some readers were immediately put off my an moc website posting such a “flamboyant” and “femme” item. But, why does a jeweled necklace have to be considered either femme/feminine or “appropriate enough” for butch/masculine? Why can’t it be just a necklace? It’s hard to run a style blog that addresses these issues when some of our target audience is still trying to achieve a very specific aesthetic that they rightfully feel has been denied to them or that, through adopting it, has caused them to be the target of oppression/discrimination/violence.

But, when I say I want to see a comprehensive dapper femme piece, I am speaking selfishly as someone who is a self-identified femme because I’d love to see the history, contributions, and origins from that particular perspective.

Thanks for your thoughtful response Anita! Sorry for calling you Anne just before, I was replying late at night and didn’t read as closely as I should have. Thanks, I now see that you get what I was saying, and I also understand myself now what you meant when you talked about the Test Shot earlier.

“But, when I say I want to see a comprehensive dapper femme piece, I am speaking selfishly as someone who is a self-identified femme because I’d love to see the history, contributions, and origins from that particular perspective.”

I don’t think it’s selfish! I think it’s great. It’s not a perspective that gets much air time and it deserves a mention.

“I wanted everyone to know that I wasn’t straight (baby gay seeking other baby gays)”

This is me!!!!

I am still attempting to find my queer style. I am a baby dyke at the ripe old age of 31(i just came out this year). I really like the aesthetics of the dapper style but I haven’t quite found the balance between dapper/femme style that works for me. I’m still attempting to find comfort in my dapperness.

Completely 100% obsessed with that tie/ statement necklace combo. Also, I feel like I learned a lot reading this, so thanks.

GUYS. GUYS, I HAVE A GREAT IDEA. Will someone please start a Bombfell for dapper queerladies? I would love to pay a dapper lady with a better sense of style than me to pick out some clothes for me, because I’m woefully inept at this. It would be like Christmas every month!!! (PLEASE DO THIS, SOMEONE WITH CLOTHES SKILLZ, I PROMISE I WILL BE YOUR FIRST CUSTOMER). :D

(Bombfell link here if you haven’t seen it before: http://www.bombfell.com)

How do i ended up in the gay zone of the internet again?

Luck?

I loved this article, all the history and references especially.

When i have tried on dapper, it has never quite felt like it fit, but reading this, and particularly taking the chance to reread the discussions of feminine masculinity have made me want to try again :) thanks