The other day, over drinks with a coworker, I had an experience that left me with a bad taste in my mouth. I was scrolling through my Facebook feed and lamenting how I couldn’t get any good news. When he asked what I was reading I told him I was feeling enraged about the Michael Brown shooting. He blurted out, “Oh, I’m torn on that one.” I did a little Scooby Doo inquisitive grunt, “How so?” “Well,” he admitted, “maybe it’s just that I don’t know enough about it, but didn’t he rob a store?” Cue face-palm.

I tried my best to remain calm while I explained that it doesn’t matter what he did or did not do, because he did not have a gun. Like, that’s the only important part of this story, and the one part that people seem so quick to gloss over. Even very nice people like my co-worker, who later came to his senses saying, “Wait a minute, I hate the cops. I have no idea why I just tried to make an excuse for the cops.” The answer, my dear friend, is racism. And no, I do not mean that my co-worker is racist (at all), but it is racism that led him to believe that somehow this unarmed young Black man deserved to be shot; racism perpetuated by conservative news media, apathy, and the myth of colorblindness. It is the act of scrolling through headlines, glancing over your neighbors shoulder at their copy of the New York Post, and taking their smear campaigns at face value that perpetuate prejudice.

This is not — despite my little anecdote — an essay about racism (for a change). This is an essay about searching for the most effective ways to engage those ambivalent, apathetic, or misinformed people who might otherwise find themselves on right side of justice. Because people without a vested interest in justice rarely take it upon themselves to open their own eyes to the micro and macro-aggressions oppressed people face every day of their lives, the onus falls upon us to blow their minds wide open. But how?

One way is through the education system. Changing attitudes early on, and in higher education is one way to get people to self-reflect and change their potentially problematic or incorrect beliefs. We can also hope to access this demographic online, but when we share our underground media perspectives on our Facebook and Twitter feeds, most of us are sharing it with the people who already share our beliefs. When we are out in the street protesting, those who disagree with our cause see us as a nuisance. And forget about clipboard canvassers. Even I cannot stand clipboard canvassers. My point is that if these people already think liberals and radicals are blowing things out of proportion, they are going to see our outrage and visible activism as blowing things out of proportion. Solidarity is so very important, but when do I get to convert some young Christian conservatives into crunchy hippies? I went looking for the loopholes. What I found was mostly discouraging.

In a May 2014 New Yorker article by Maria Konnikova titled “I Don’t Want To Be Right,” researcher Brendan Nyhan set out to change people’s perspectives on hot-button current events issues. His research focuses on correcting people’s factually incorrect beliefs about things like the Iraqi insurgence, or the “dangers” of vaccinating your child. What he discovered through trial and error after error, is that it’s almost impossible:

At first, it appeared as though the correction did cause some people to change their false beliefs. But, when the researchers took a closer look, they found that the only people who had changed their views were those who were ideologically predisposed to disbelieve the fact in question. If someone held a contrary attitude, the correction not only didn’t work — it made the subject more distrustful of the source.

So, basically, if you try to tell a liberal that Mike Brown was shot because he was Black, they will probably believe you, but tell it to a conservative, and he’ll dismiss it as propaganda, pretty much without fail. To get an idea of how this works outside of a laboratory setting, I spoke with one ideological convert, LJ Beckstein, a student at Hampshire College, who shared his experience with a change of attitude:

I’m from Cornwall, New York, which is a small town three counties above New York City. Wikipedia tells me it’s 95% white, which makes sense. The town’s pretty split politically, but split between liberals and conservatives — nothing too radical happens there. Growing up I learned, through a combination of my parents and school and TV and books, that here in America, we were post-race and post-gender and post-everything. I was taught the theory that we were all created equal, and not how that (didn’t) play out in practice. I don’t know how I picked this idea up, but I was under the impression that affirmative action existed as the government’s official apology for slavery. I didn’t know anyone who was really rich or anyone who was really poor… Because I thought that everyone had the same opportunities, it seemed like capitalism was a fair way that the hardest workers succeeded and lazy people didn’t. It’s funny, because I clearly had an instinct for activism. I started and ran my school’s GSA. I was notably the liberal kid in class who would always fight with the Republican teachers. I decided to go to Hampshire College in large part because I had heard it described as a yearlong activist camp. So once I got there and I learned about — well, basically everything — pretty much all of my opinions instantly changed. It wasn’t hard or painful, and I wasn’t ashamed of how I’d seen the world before. The way I understood it is that I just didn’t have access to the information… I had never been given reason to question what I’d learned. (Which, in my understanding, is pretty much exactly what privilege is.)… I wonder how much patience Me now would have if I met the Me who believed all those things.

Because LJ was leftward leaning, it wasn’t difficult to accept these new truths, but had he been from the conservative side of the tracks, this transition might have been a lot more uncomfortable. In fact, it likely wouldn’t have happened at all. First of all, he probably would not have attended Hampshire College, a liberal bastion. Second, according to Professor Nyhan’s research, the introduction of this new information might have had a backfiring effect. Nyhan attributes this phenomenon to an almost religious attachment to our political affiliations:

If someone asked you to explain the relationship between the Earth and the sun, you might say something wrong: perhaps that the sun rotates around the Earth, rising in the east and setting in the west. A friend who understands astronomy may correct you. It’s no big deal; you simply change your belief.

But imagine living in the time of Galileo, when understandings of the Earth-sun relationship were completely different, and when that view was tied closely to ideas of the nature of the world, the self, and religion. What would happen if Galileo tried to correct your belief? The process isn’t nearly as simple. The crucial difference between then and now, of course, is the importance of the misperception. When there’s no immediate threat to our understanding of the world, we change our beliefs. It’s when that change contradicts something we’ve long held as important that problems occur.

Our understanding of the world today, at least in America, is one of an ideological dichotomy: Liberals versus Conservatives. Every issue, be it race, the environment, or women’s rights, is split up like this: They think this thing, We think the exact opposite, with no room for the multitudes that exist between (and for no very apparent reason other than accruing votes). The arguments that occur across parties are essentially shouting matches. They call one another terrible names, sling mud, and actually do one another favors by further polarizing their views.

Nowhere is this more evident than in the way we consume our news. In a 2009 study of news media viewers and readers, entitled “Red Media, Blue Media: Evidence of Ideological Selectivity in Media Use” the researchers found that not only do consumers have a tendency to commit to sources that espouse opinions that align with their already held political beliefs, but media outlets cater to this trend: “The emergence of Fox News as the cable ratings leader suggests that in a competitive market, politically slanted news programming allows a new organization to create a niche for itself… Under competition and diversity of opinion, newspapers will provide content that is more biased.” Their motivation to do so is purely driven by profit, or they run the risk of losing out to competitors, both liberal and conservative. “Thus, as the audience become polarized over matters of politics and public policy, rational media owners stand to gain market share by injecting more rather than less political bias into the news (Gentzkow & Shapiro, 2006).”

As for how this trend affects voting, author Andrew Gelman says this in his book Red State, Blue State, Rich State Poor State: Why Americans Vote The Way They Do that “polarization serves as a useful function insofar as it makes party brand names meaningful, ultimately making elected officials more accountable to relatively uninformed voters… Social scientists who study American political elites have generally concluded that politicians have become substantially more ideologically polarized over time.” In this way, the issues we fight for in America which are so inextricably tied to our political and moral beliefs, that an opposition is born at the moment the issue is created. They exist harmoniously in opposition to one another. The further Right goes the right, so does the Left go left. However, Gelman goes on to note that “although Americans have become increasingly polarized in their impressions of the Democratic and Republican parties… each person maintains a mix of attitudes within himself or herself [sic].” Middle and lower class conservatives and liberals, as individuals, see themselves as very complex. It is within these complex understandings of the self that we find an opportunity to change people’s attitudes, especially concerning social issues. Politicians are not going to change their stance because a radical, partisan opinion is what will get them into office, but it is possible that their constituents could make them change their tune.

Using a theory developed by researcher Claude Steele, Professor Nyhan was able to make some small progress in narrowing this divide. It was done not by forcing facts into people’s hands, but by stroking their egos. “The theory… suggests that, when people feel their sense of self threatened by the outside world, they are strongly motivated to correct the misperception, be it by reasoning away the inconsistency or by modifying their behavior.” So, the researchers performed self-affirmation exercises along with the corrective information: “On all issues, attitudes became more accurate with self-affirmation, and remained just as inaccurate without. That effect held even when no additional information was presented — that is, when people were simply asked the same questions twice, before and after the self-affirmation.” This sounds kind of bananas, but the science suggests that if we are more likely to accept factual information if we are able to feel good about ourselves while making the change of opinion. Nyhan admits that “it’s hardly a solution that can be applied easily outside the lab. ‘People don’t just go around writing essays about a time they felt good about themselves… And who knows how long the effect lasts — it’s not as though we often think good thoughts and then go on to debate climate change.’” Right, but this is the loophole I was looking for.

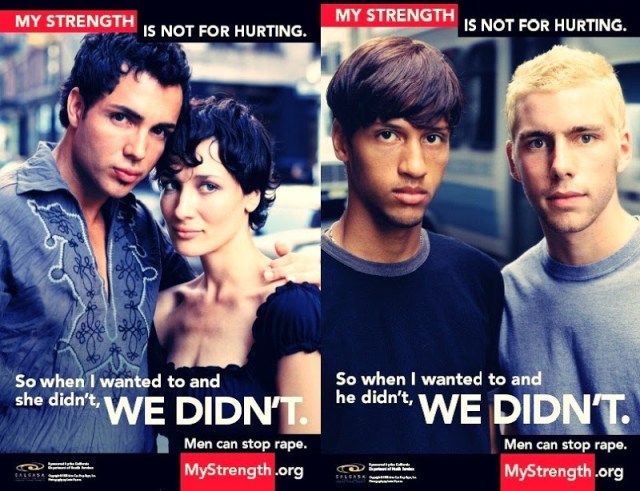

Making a change of opinion can be life-altering, which is why it is important that people feel unthreatened while making that change. Often, this change happens in a college setting, a (mostly) inherently nurturing and self-affirming environment in which we are encouraged to take challenges and have a cadre of professionals and classmates there to take the jump alongside us. It can be difficult to address people with problematic or hateful views with anything but spite or shame, but in campaigns to win over those “swing votes,” it appears we might catch more flies with honey than vinegar. For instance, a 2010 ad campaign launched by the group Men Can Stop Rape focuses on the strength men can find within themselves to prevent rape scenarios, using the tagline “My Strength Is Not For Hurting.” While the campaign does raise some eyebrows around the complexities of gender, “strength,” and rape, the intention is self-affirming. This stands in stark contrast to a 2013 UK anti-rape campaign featuring a woman in her underwear, stating “Have sex with someone who hasn’t said yes to it, and the next place you enter could be prison.” Aside from the atrocious run-on sentence, the ad is threatening. A threat like this, Professor Nyhan might say, would cause a person to go into defense mode and dismiss the message as propaganda. Certainly I’m not arguing that the person would leave the scene and go on to commit an act of rape. I’m saying the message would be lost on a person who is otherwise ambivalent about the issue of sexual violence against women.

Are there other ways to access our peers in meaningful ways? It is sometimes said that people who hold the strongest prejudices are hiding an insecurity about themselves; that people with homophobic views might just be gay themselves. While I prefer to respect a person’s right to self-identify, we stand to learn something from stories like this, which is why I offer you this nugget of inspiration from our very own Helen McDonald:

I had decided to go to a pre-orientation program my first year of college… It was called the “Third World Transition Program” and it was comprised of a weeklong series of workshops that taught about identity politics, social marginalization, and various axes of oppression. I understood nothing about systematic oppression before college, and as far as I was concerened, we lived in a post-racial, God-fearing, go-Amurrica society where sometimes bad things happened to good people, but most people deserved their lot in life. I was a conservative preacher’s daughter, who endorsed a lot of homophobia but justified it in the name of religion. I didn’t really like how society treated women, but I didn’t have the tools to really articulate my ideas, and I rarely thought that my race affected the way society treated me, even though my parents tried their best to warn me about racism. Throughout my first week of school, I had my mind blown time and time again… The counselors announced that the day would be devoted to the topic “Homophobia and Heteronormativity.” In my mind, homophobia was murdering someone gay and I didn’t do that so I didn’t really have anything to learn from those workshops. In fact, I almost skipped that day because I was afraid of what I’d learn, and that indulging “the gays” would send me to hell… The counselors greeted us with white sheets of paper taped on the walls around the room, with different words on it. Our job was to write whatever words came to mind when we thought about those topics… Eventually I came up to a piece of paper that said “internalized homophobia,” that had been decorated with a series of adjectives and nouns, written by my peers… It felt like I was reading a poem about my life, and about all of the times I had wished myself “normal,” or projected hate onto the same gender couples, or gender non-conforming people because they were free in a way I could never be. I’m not even sure I was able to write anything on the sheet of paper. I returned to my seat, and the counselors opened the floor to queer people who wanted to share their stories. Many people came out, and others talked about their life journeys; I sat alone and tried not to cry, wanting so badly to be strong enough to stand up and speak my truth. After the workshop, I went back to my dorm room, and texted a friend: “I’m sorry for not understanding who you are, and for judging you when you came out to me. I know now that nothing is wrong with you.”

“Also I think I’m gay.”

Helen, rather than self-affirmation, had an experience of self-identification. She was confronted with a truth that existed within her in a supportive environment. It is worth noting that the experiences of both LJ and Helen happened in a college setting, and there are a lot of people who either cannot afford a college education, or who are beyond the point of going back to school. It’s more difficult to figure out how to create these attitude changes outside of a classroom, but if we are able to pinpoint the moments when these changes happen, we can work towards recreating them organically in the “real world.” Personal narratives are far more compelling than scientific journals and psych experiments.

So, to that end, I’m inviting you to share your experience with a change of perspective, large or small, to create a little archive from which we can draw inspiration. Right here in the comments. In this way, whether you want to start a movement in your community, or you’re just trying to get your high school friends to stop using the phrase “that’s so gay,” we can draw from our shared experiences.

Comments

I really, really love your work, Hannah. Great article.

A lot of things and instances come to mind reading your prompt at the end — I have convinced people (more in college) to stop saying “that’s so gay” by simply asking them to and explaining that when they use the word in that manner, it makes me feel unsafe around them, like I can’t be who I am. More recently, I’ve found myself in conversations with straight cis people who find all the different queer “labels these days” confusing and exhausting, and siting that as a reason to not try. Or even a reason to use slurs — that argument has been used when I mentioned that a colleague said tr*nny. And I’ve struggled with that kind of attitude, trying hard to understand what that exhaustion might feel like and how, using empathy, to pull them into putting in the effort to understand without seeing understanding and respecting people’s rights to identify differently from them as a chore. But if we’re talking about triumphs, I will say that the loop hole you described has been true for me — the making people feel good while working to help them change their beliefs. Primarily with my family. There were a few instances at my brother’s wedding last year (the pastor made homophobic comments during the service) and my family did not step up to bat. As a result, in September, I sat each of them down and explained, using my own personal narrative, how my queerness is central to who I am, and that when someone (like the pastor) says things like that, he’s talking about their child. And that they have been so supportive so far, and that I need them to be even more supportive — I need them to be in my corner publicly and privately. I feel like since those conversations, my family has been more open to talking to me about my experiences, and to hearing me talk about what’s important to me. On the large scale, it is a small triumph. And my brother still doesn’t understand, despite me using the same tactics and conversation, that attending a church where the pastor is anti-gay is contributing to homophobia. So there’s still conversations to be had.

Thanks for the prompt! I’ll be thinking about this more and more, especially in terms of my own personal changes in perspectives about a wide variety of crucial things, too.

As a half-American and half-European, I feel like Democrats and Republicans are so politically similar it is difficult not to find common ground. If the international political spectrum was a color spectrum, these two parties would be like blue and purple. Different, but really, really close. The fact that the debate only explores blue and purple and ignores all the other colors really bothers me and makes it difficult for me to talk to anyone. If I talk about Obama’s corruption, people assume I am a Republican. When I tell them I am left wing, they just get angry and defend their political party. Noam Chomsky said that the best way to control a population was to have a very, very narrow spectrum of possible ideas, but then to allow extremely passionate debate within that spectrum. It is hard to really see the Democrat vs. Republican polarization any other way. I certainly believe that complex feelings allow people to be open to change and possibly leave behind racism and homophobia, which is great, but it becomes depressing imagining the huge gap between the current state of affairs and a democracy in which these painstakingly won hearts and minds would actually make a difference. There has been a massive swing to the right in the past few decades, and only the increased rights for monogamous white LGB people really represents an exception to this. And have you ever tried to call out a Democrat over the age of 30 on racism? “I can’t be racist – I’m a Democrat!”

My ex-girlfriend’s mom switched all the way over from passionate Republican to Democrat, though, so that is nice….but since both parties are currently pro-war in regard to Iraq and Syria, that position still spells death for many.

This is such an important topic, and a really well-written article! I know I usually just get frustrated and give up when I’m trying to change someone’s mind about an issue that’s important to me. I think it’s because the people whose minds I try to change are important to me, just as the issues are, so it’s very hurtful to see someone you love continue to hold beliefs that go against yours.

The most effective way that my own mind has been changed is actually through reading books. Fiction. Whenever I read, I put myself in a completely different world. It’s like that study that came out recently that said that reading Harry Potter actually made kids more empathetic. So maybe, if you’re trying to change someone’s mind about something and make them see a different perspective, you could recommend a book for them to read that would put them in that mindset.

I’ve been trying with great difficulty to talk with people about the Michael Brown case. Most people I talk to share the view you open with, which is that the only thing that matters is that he didn’t have a gun. What most people don’t realize is that nowhere in our country’s laws about police use-of-force does it say a person has to have a gun for an officer to shoot. And in our country, our main expectation of police is that they enforce the law. This leaves room in their training and their job description for shootings of unarmed people. Are there racist cops? Of course. But I challenge everyone reading this, especially under the shadow of this important article, to look deeper, understand our expectations of the police, and draw measured, educated conclusions.

I understand and respect that in dangerous situations police do have the right to shoot even if the suspect doesn’t have a gun. However, the officer needs to try non-lethal methods of subduing the suspect.

There’s also no law requiring the police to attempt “intermediate” forms of force. I’m not trying to defend the police. I don’t know what happened between Officer Wilson and Michael Brown. I’m just trying to get people to understand the law before they draw conclusions, as ultimately the responsibility is on us to lobby to change our laws if we feel they’re unjust. Instead we would feel satisfied with the prosecution of an individual police officer, which likely won’t stop this from happening again.

The entire push back against police militarization is an attempt to lobby to change laws. The push for community policing is attempt to encourage intermediate forms of force.

I think people understand the laws and are trying to change them. I think the focus on the fact that Michael Brown didn’t have a gun is an attempt to bring attention to the fact that the police officer’s response was over-zealous. Once attention is brought to that fact. Then you bring up specific laws that are encouraging over-zealous responses.

The strategy for opening a conversation is different from bringing attention to specific laws.

I agree with you, a multi-pronged holistic approach is important for change. Which is why it’s been so disappointing for me that law has been left out of the conversation, at least in the media I’ve consumed and the conversations I’ve heard. There are a lot of misconceptions out there about what the law is and what it can affect. For instance, police militarization is an entirely separate conversation. Referring to “the laws” is actually somewhat inaccurate. Most would be surprised to know there aren’t really statutory regulations. Most of our use-of-force restrictions come from Supreme Court interpretations of the Fourth Amendment (force is considered a seizure by the court). It’s some really good reading for anyone who’s interested. And for anyone who knew that already, my apologies.

I think it’s very difficult to change minds and I don’t try to. I offer respect and expect the same in return. The last big issue I changed my mind on was religion. I used to be very much atheist leaning. I was often horrified after learning about religion as a child. But I now respect the community aspect of religion. And think people have their own path.

Just yesterday I overheard my mom talking about “illegals” and “illegal aliens.” Afterward I asked her to please not use those terms, and recommended undocumented migrant instead. She asked why, which surprised me because I thought she would know better, so after a pause, I just said, kindness. I know there are essays written about why illegal isn’t legally correct, nor is immigrant, or certainly alien; but in that moment I thought I could better motivate her by encouraging kindness. And it seemed to work, she mulled it over and said thank you.

I love this article. And this quote is everything:

“It wasn’t hard or painful, and I wasn’t ashamed of how I’d seen the world before. The way I understood it is that I just didn’t have access to the information… I had never been given reason to question what I’d learned. (Which, in my understanding, is pretty much exactly what privilege is.)… I wonder how much patience Me now would have if I met the Me who believed all those things.”

I studied science in school and always felt out of the loop with the queer community. From my experience studying in STEM, your whole college life revolves around it and there wasn’t room to learn about social issues or make friends outside of the program. There were also very few LGBTQ folks studying science, so my environment was mostly heteronormative. I could extract DNA like nobody’s business but I didn’t know much about social issues affecting the queer community. It seemed that every queer person I really wanted to get to know was a WGS or queer theory major and I simply didn’t have the vocabulary or the knowledge to feel like I could keep up with them during conversations, so I stopped trying. It wasn’t until I took a gap year post-college that I was able to do some critical reading and observation to educate myself on queer issues and make decisions on what I think is important.

So my reason for sharing this is, like the speaker in the quote above touches on, I think we should be aware of the barriers of privilege we create for ourselves when we choose to immerse ourselves in a specific form of thinking. That comfortable, safe, bubble filled with our chosen people who agree with us on everything and think like we do. But there’s a whole world outside of that bubble with minds that can be changed. Some of those people on the outside want to be inside our bubble too, but sometimes we don’t notice them because they’re not on the level of understanding we are. That’s something I’ve learned post-grad and am really internalizing as I continue to educate myself on worldly issues. Give everyone a chance. We’ve all been the person on the outside wanting in. If we want to win battles, we need more people on our side. We don’t need more division and enraged wars and polarized views, that’s what creates bloodshed and staggers change. We need to open up our bubble and let the allies filter through.

I very much love this article and thinking about this. I think context, story, experience and relationship play big roles in people’s minds changing. Also, a lot of times real change happens pretty slow. I feel like I’m changing my family’s minds about things, but very slowly, and kindness is leading the way. Because they love me, they try to understand me, in trying to understand me and my experiences, their view on the world shifts a little. My family background is conservative evangelical Christian.

Story: my dad was going on in this manner: “LGBTQRSTUV…. I can’t keep up! Lesbian, ok I know what that means, Gay, ok, got it, Bi, they don’t even know what they want..” And he knows I identify as bi and I got my hackles up and he backed off, only to go off ranting again. I felt my blood pressure rising and then suddenly I checked it and said “well, do you want me to educate you?” He stopped mid-sentence, “well, actually…. yes.” So I found myself explaining to my parents all these terms and identities and why I identify as both queer and bi but why pansexual doesn’t click with me. I talked about my own desires and experiences and the biphobia I’ve encountered and all this stuff I never though I’d ever share with them. It was so weird. They were curious and respectful, I was frank. A couple of weeks later my dad said something about “You know I’ve been thinking about what you said that some people assume you’re more likely to cheat because you’re bi… that just doesn’t make sense- I’m sorry you face that.” But it’s not like and boom, now their minds are changed, it’s stop and go. My family, including siblings and their spouses have been shifting politically too, and I feel like my work as a community organizer and talking about the issues and people’s stories have had something to do with that.

My brother-in-law did tell me the other week that it would be really hard on the family if I ended up with a woman, which is still so frustrating, and why would he feel the need to tell me that anyway? Still, I think there’s hope in honest sharing and a groundwork of respect and trust.

Another story- I’m not super-out at work, but after one of our members said some really terrible homophobic stuff I felt like i had to come out to him, for my own integrity. It was uncomfortable but not awful, and he didn’t say that stuff around me after that. Months later he told me that sometimes he thinks he might be gay, so…

Our organization did some solidarity work with workers trying to organize a union and we had one member who was skeptical about the union and sort of repeating the union-busting p.r. soundbites. We had some group conversations that were just very gentle, and non-judgemental, but presenting things he hadn’t known about and perspective he hadn’t considered. I witnessed him come around and understand it. Another example- we have an activist who looking at the education system had swallowed the anti-teacher rhetoric, until she started getting really involved working and volunteering in the school. She’s done a 180 and is advocating for increased and fair funding and is anti-corporate reform etc… It took being in that context and getting to know teachers and seeing the situation from that perspective.

I love thinking about how and why people shift and change. It’s part of my job. I think about it in the organizing I’m doing now in a neighborhood with a lot of tension between the older home-owners and the section 8 renters. Both groups could come together around the issue of slumlords, and I feel like getting to know each other and each others’ stories and struggles, and working together towards a common goal… there might be hope of attitudes shifting.

I myself shifted a whole lot, from conservative Christian, scared of sex, terrified of facing my sexuality, clueless about social justice to non-religious spiritual rejecting Christianity as hierarchical and repressive, identifying as queer, sex-positive, progressive activist. Leaving my religious identity in college was terrifying. So much of my shifting has had to do with people I’ve met, stories I’ve heard and experiences I’ve had, as well as of course how I’ve thought and interpreted it all.

Thanks for the well-written thoughtful article!

This is one of the most interesting articles I’ve read in a long time. It articulated beautifully some ideas that I’ve been having for a while, and gave me lots of new things to think about. Also love all the commenters’ stories of changing minds with kindness.

I love this article and all the comments are wonderful. At first I couldn’t think of any experience of my own to share, but then it hit me. I never thought of myself as ignorant of important topics until I discovered Autostraddle. This website has changed my mind in kind, constructive ways over the past few years. I knew almost nothing about people who are trans or queer WoC and their struggles even within the lgbtq community.

I love this website and thank you for writing articles like this.

Wow, thank you Hannah. I will come back to this. I’m trying to work on some family members. I second the importance of fiction and slowness. My dad, who has a fancy degree and a lot of power over people’s lives, learned from a colleague – it mattered to my dad that this was a colleague – that overwhelmingly only black and brown kids get graffiti and trespassing on their juvenile records. I told him ‘any high schooler could tell you that.’ I then asked him ‘what would it take for a room full of prosecutors to actually get that?’ He paused . . . and said . . . ‘I don’t know.’

That is the most effective conversation I’ve had with him and he’s a very well meaning, very privileged liberal.

For me, getting to a place of actively deconstructing white supremacy in my mind, my life, my family, and my community is very slow. Ten years ago I attended a conversation about race at my family’s church, and as by far the youngest person in the room said something very postracial about my peers. The older black people in the room listened tolerantly. I still feel some shame about that, but shortly afterwards I realized all the ‘young people’ I was talking about were white.. . and that was the start of a lot of questions.

ps – rereading, ‘most effective’ sounds defeated or petulant – actually I think he really thought, and I will keep up that kind of question, and I think maybe maybe in 10 years it might actually come out in his actions. Cheers to the long haul for myself and others.

Hannah thanks again for this. This helped me call in my CEO on something really unhelpful she said about cissexism, and she responded positively in words for now.

I’m so glad! Do let me know how it works out for you, ultimately. The best way to test these theories is in real life!