feature image via Shutterstock

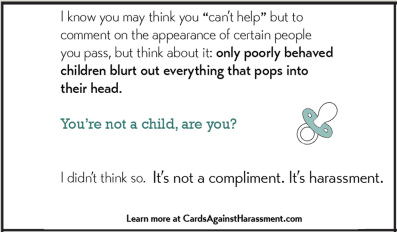

One brave Minnesotan, Lindsey, is doing the thing we have all wanted to do: giving catcallers a taste of their own bitter, shameful medicine. She does this by handing her street harassers clever little calling cards informing them of their transgression. Not only that, but she is secretly recording her interactions with them and putting them on the Internet. The whole wide web is now privy to the genuinely horrifying things some men think are not only okay to say to women, but which they justify with either biblical text or simply personal opinion (read: patriarchy). Every time I am told anything from “why don’t you smile,” to “I would tear that _____ up,” to other things not fit to print, I walk away red-faced and ashamed. In my imagination, I do a double back flip and land my spiked heel directly into the eyesocket of my offender while delivering a dead-on one-liner. Though I was a pretty accomplished gymnast in my middle school days, I have yet to fully hone my femininja skills.

So, I have developed a rubric for my walk to work. If you are my neighbor and you wish me a good morning, and it is indeed a good morning, I will respond accordingly… no eye contact. If you tell me I am beautiful on a day when I am feeling particularly beautiful, I might even say thank you. Anything beyond cordial compliments receives a stone-faced side-eye, because no matter what you say, all I hear is, “I would like to undress you with my eyes.” I am reminded of the time a man walking with his toddler comically tripped over and knocked down his own child in an attempt to get a look at my backside. It is also not beyond my perception to realize that the majority of these interactions are with men of color. This could have plenty to do with the fact that I am a woman of color living in an urban area, and by no means am I implying that white men have never harassed me, but the fact remains.

There is something utterly cathartic about watching another woman stick it to the man, and to, in her own words, provide men “a platform to embarrass themselves in a way that they’ve already embarrassed me.” However, it is hard to ignore the plainly evident: the majority of the people Lindsey embarrasses are men of color. Despite protestations that she has approached both white men and women about street harassment, Lindsey’s videos clearly illustrate the disproportionate prevalence of street harassment in communities of color (read: poor and working class urban communities).

In one video with a Black man Lindsey names Jared, we hear this interaction:

J: You know why I feel [police give men tickets for catcalling]? Because white women get offended…

L: No, no, this has nothing to do with race…

J:…when Black men approach them, so they created a law to do that.

L: Nope. Listen. I’ll yell at white men about this. I’ll yell at women about this. The point is, I should be able to walk down the street, just like you should be able to walk down the street…

J: Yeah. I’m glad that you approached me and told me that women get offended about that…

L: I encourage you to e-mail me. Check out the website…

J: I’m not upset, but I’m a grown man. I’m gonna keep talking to women the way I want to talk to them.

L: And I’m encouraging you not to.

You can call it “pulling the race card.” You can call it “white-splaining.” However, it is clear there is a racial and cultural element that Lindsey is anxious to avoid by literally cutting Jared off. When a Black person says to a white person, something racist is happening, it is said white person’s responsibility to respond by saying, you might be right, please explain. Lindsey has been quoted saying, “Though I’m filming as I’m encountering experiences, I’m in no way attempting to target a specific demographic…Sexism is sexism.” Sure, Lindsey isn’t seeking to approach men of color (though, her daily commute involves public transportation, mostly used by people of color), but in the end these are the men who end up lambasted on her website. “Sexism is sexism” is exactly the kind of language used to deny any kind of intersectionality within the feminist movement. It is the kind of language that sparked #SolidarityIsForWhiteWomen. It is the kind of language that denies Black women the agency to approach problems that are prevalent in their own communities.

In the FAQ section of her blog, Lindsey has this to say about the race dynamics in her videos:

I am cognizant that we live in a world that is extremely hostile towards black men and am very troubled that some will watch my videos and draw prejudiced conclusions from them. The continuing vice of racism is that if I had a dozen videos of white men catcalling, it would just be considered a “male” problem, but if people see a dozen videos of black men catcalling, they somehow think it depicts a “black male” problem. It doesn’t.

She does point out that she knows women of color experience street harassment at a much higher rate than their white counterparts — 41% of Black and Latina women, versus 24% of white women, according to a 2014 SSH Report. (Not to mention, of course, that trans folks, especially trans women of color, are at an even higher risk for violent interactions in the street). By placing an “I promise I’m not a racist” disclaimer on her videos, Lindsey persists in denying her white privilege. This does zippety-do-dah to advance her feminist cause. It also does nothing to broaden the conversation around street harassment, which is all too often told from the perspective of cis white women. In Lindsey’s unwitting attempt at appearing color-blind, she expresses on her website that she does not endorse the criminalization of street harassment:

My goal is not to criminalize verbal street harassment, for a few reasons. First, the long history of institutionalized racism in our criminal justice system has not made me confident that laws against street harassment would be applied uniformly or fairly. But more importantly, I believe street harassment is fundamentally rooted in belief systems about women, which are more meaningfully eradicated and improved through social change, education, and advocacy.

However, if we take a moment to picture Lindsey’s interactions in the street — a white woman having a very heated argument with a Black man she clearly does not know — it is not difficult to imagine they might attract the attention of a nearby police officer, or that a concerned/confused bystander might call the police. Given her dedication to education over criminalization, Lindsey seems generally unaware of the picture she is painting by wielding her privilege in a public space.

As an individual, nobody can deny Lindsey the right to criticize the men who make her feel unsafe or humiliated walking down the street. As an activist, and a participant in a movement, we have to question the possibly counterproductive effects of a white woman publicly taking the wheel on an issue that would be better handled by the people that Lindsey herself acknowledges suffer from it more often: women of color.

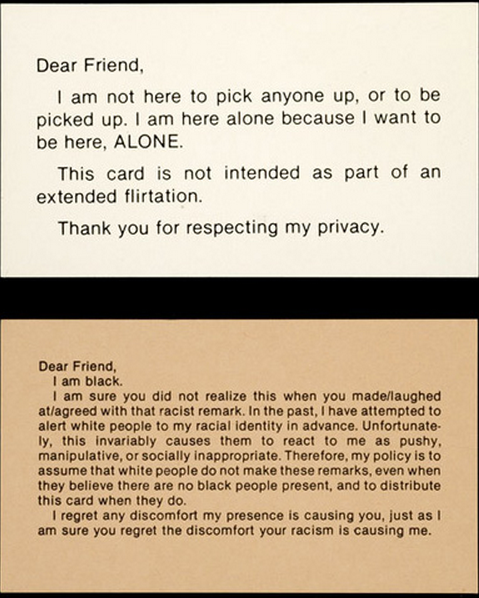

IN FACT, as writer Aura Bogado has graciously pointed out on Twitter, this calling card concept has already been done. Not only has it been done, it has been done with special attention to race and gender. In 1986, artist Adrian Piper penned a couple brilliant calling cards that addressed both men who try to pick up women who are alone, and people who inadvertently (or advertently) perpetuate racism in public. Lindsey insists she was unaware of Piper’s work until after she started CAH, which is entirely possible. The point is, Lindsey lacks a modicum of self-awareness around issues of race and class that make her ill-suited to bear the cross of the anti-street harassment movement.

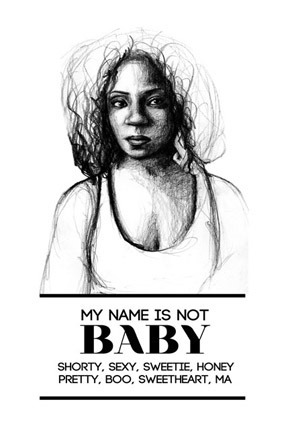

On her blog, Lindsey does pay homage to another contemporary anti-street harassment campaign called Stop Telling Women To Smile. The artist, Tatyana Fazlalizadeh, “takes women’s voices, and faces, and puts them in the street — creating a bold presence for women in an environment where they are so often made to feel uncomfortable and unsafe.” This kind of advocacy, while not as direct as Lindsey’s approach, works as a form of empowerment and literally leaves its mark on the communities in which this kind of behavior is most egregious.

Hopefully, women like Lindsey and Tatyana inspire women of all creeds to challenge catcalling. The more men hear that their attention is unwelcome, the more I get to wear booty shorts as often as I like (all the time). However, let’s be cognizant of where and how we approach these situations, both for our personal safety, and for the sake of The Greater Good. Trust that there will be video documentation when I receive my femininja black belt. Until then, I will be joyously telling the harassers on my block to kindly go f*ck themselves, because they’ve not a chance with me.