Header by Rory Midhani

Feature image via shutterstock

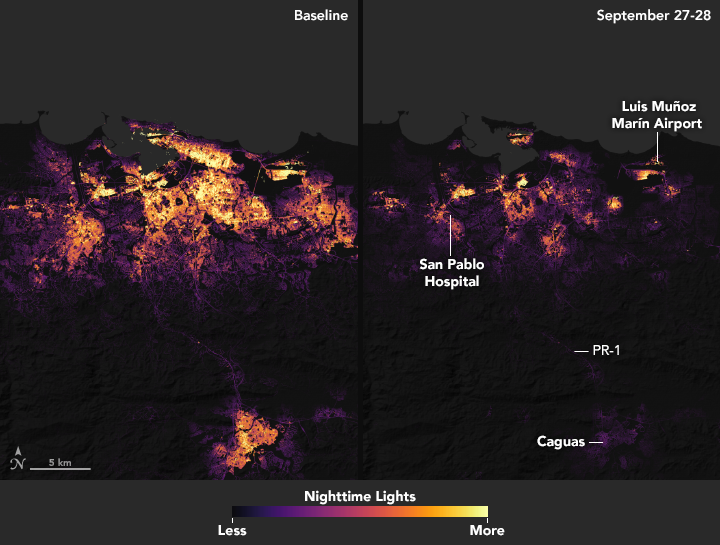

Hurricane Maria made landfall in Puerto Rico on Wednesday, September 20, causing catastrophic damage as the Category 4 storm tore through the densely populated archipelago. Winds reaching up to 175 mph knocked out electricity for all 3.5 million residents of the unincorporated U.S. territory. As of October 2, 95% remained without power, and according to the latest estimates, electricity will not be fully restored for 4-6 months. With computer and communication systems down, officials have not been able to get an accurate death count. Regardless, it’s clear that the prospect of months without power tops the list of long-term obstacles for Puerto Rico.

Among the many news reports and opinion pieces on the situation, from Breitbart to Wired to Time, a common theme has been to cite the rebuilding process as an opportunity to implement renewable energy. From a September 29 editorial in Bloomberg:

The Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority, the biggest public utility in the U.S., is notorious for its mismanagement and is currently bankrupt, with $9 billion in debt. Puerto Ricans pay more for electricity than nearly all of their fellow Americans (except Hawaiians). They get most of it from dirty oil-fired plants — many of them decades old — on a system prone to outages and blackouts. By some accounts, the system loses as much as 12 percent of its revenues to power theft and faulty billing, three times the U.S. average.

The collapse of the grid, which will cost billions of dollars just to restore, has amplified calls to privatize Prepa. … However that process plays out — and some form of privatization seems both desirable and likely— a few goals should be paramount. For starters, Puerto Rico needs to replace its oil-burning plants with those that burn cleaner natural gas. It also needs to expand its use of renewables, which provide less than 3 percent of electricity— well below the 15 percent in the U.S. as a whole and trifling for an island blessed with sunshine and wind. … The larger challenge, for both Puerto Rico and Prepa, is creating a stable, pro-growth environment that will attract investors.

On the face of it, any occasion where liberals and conservatives alike are calling to help a marginalized community while simultaneously “going green” sounds like a major win. But there are some additional factors worth considering here — namely, a legacy of colonialist exploitation in Puerto Rico, and the phenomenon of “disaster capitalism.” Let’s take a closer look.

US Colonial Control

The United States first annexed Puerto Rico during the Spanish-American War of 1898. Since the Downes ruling in 1901, Congress has governed Puerto Rico as a separate and unequal territory, issuing a series of contradictory rulings parsing out the exact legal status of the people that live there. This arrangement — in which the United States has exerted significant control over the economic, political and social dynamics of the island — has been repeatedly and explicitly condemned by the United Nations as colonialism, which constitutes “a denial of fundamental human rights.” Although Puerto Ricans today have US citizenship and are subject to the draft, they do not have full constitutional rights, cannot vote in US presidential elections, and do not have representatives with voting rights in Congress. Puerto Ricans are ineligible for Supplemental Security Income (SSI) or the Earned Income Tax Credit, and the island receives half the rate of federal healthcare funding even while island residents pay the same Medicare tax as residents of the 50 states.

Over the past century, Puerto Rico’s relationship with the United States has left the island in a state of economic crisis and extreme codependency. During direct US military control of the island from 1898-1900, the updated classification resulted in tariff rules that penalized Puerto Rico’s previously successful coffee sector and priced them out of European markets, dramatically reducing their export volume. Sugar instead became the dominant industry in Puerto Rico, promoted by favorable US tariff policies and colonial land taxes that forced many small farmers to sell their farms (making way for sugar’s growth as a monoculture).

Sugarcane production peaked in the early 1950s, and over the next decade, industrialization led to a continued steady output that required fewer and fewer workers. When large numbers of unemployed Puerto Ricans began moving to the mainland, the US created a policy of tax breaks to aggressively push business in Puerto Rico away from agriculture and towards manufacturing. American corporations flooded in as Puerto Rico became a tax haven for consumer goods manufacturing and pharmaceutical companies. The financial results were strong enough that the generous tax breaks were seen as creating an unfair advantage. So in 1996, Congress began a 10-year phase out, and American corporations began pulling back. Puerto Rico has since been in an excruciating recession.

For two decades now, the Puerto Rican government has been closing structural operating deficits via predatory loans by Wall Street firms “eager to market its triple tax-exempt bonds to wealthy and middle-class Americans and Puerto Ricans.” US investors have been particularly attracted by a legal provision that requires Puerto Rico to pay general obligation debt service ahead of any other expenses, as well Puerto Rico’s special status that denies them Chapter 9 bankruptcy protection. Though the loans are obviously unrealistic for Puerto Rico to pay back in full, with unemployment levels reaching 11%, labor force participation at a mere 40%, and debt coming in at a staggering $123 billion, Puerto Rico has little choice but to accept money and help wherever it can get it at this point.

In July 2016, a US financial control board was created under the Puerto Rico Oversight, Management and Economic Stability Act (PROMESA), which has since promoted austerity measures and generally failed to improve Puerto Rico’s financial problems. Meanwhile, the state has been forming “public-private alliances,” handing off profitable segments of the public sector to private industry, and saving costs by eliminating large scale infrastructure repair wherever possible… which brings us back to the current energy situation.

Power Grid Restoration

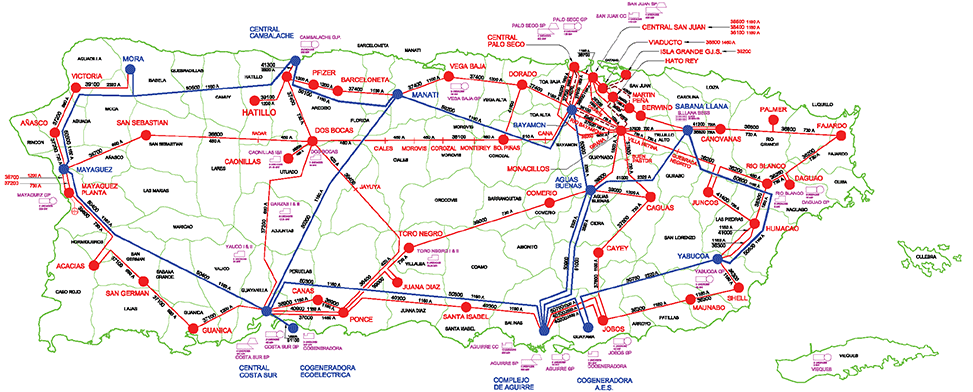

Given Puerto Rico’s dire financial situation, budget items such as tree pruning are generally not at the top of the list. This may not seem like a big deal, except that the bulk of the island’s power plants are located in the south, away from the capital. Two principal high-voltage lines from generators on the south coast must travel through mountain areas and rainforests to reach San Juan, meaning that over time, small items like cutbacks in tree pruning have left the 16,000 miles of primary power lines spread across the island extremely vulnerable. Combined with other scaled back inspections, maintenance and repairs, this has resulted in an extremely volatile power grid, with regular power outages even outside of adverse weather events.

Prior to this year’s hurricane season, the Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority (PREPA) estimated that it needed more than $4 billion to overhaul its outdated power plants and reduce its heavy reliance on imported oil. With additional millions of dollars in repairs now needed on top of that for disaster recovery, it’s no surprise to hear alternatives being welcomed.

Typically during grid recovery operations, the utility industry plays a central role in coordinating emergency efforts by having line crews come in from distant utilities. Because PREPA is a public power company, that assignment would traditionally fall to the American Public Power Association (APPA). In this case, however, Trump has appointed the Army Corps of Engineers to lead power restoration efforts. FEMA and the Department of Energy are also supporting the effort, and PREPA has contracted with Whitefish Energy Holdings, a Montana based LLC. Whitefish is sending over 400 employees to the island, some from Montana but many others sourced from utility companies in other locations — an unusual move, in that electrical utilities don’t usually work under a contractor.

“Do we feel like we’re being pushed aside [by the Army]? Hell, no! It’s an all-hands-on-deck exercise, and we feel like they will be able to bring resources that will be extremely helpful,” said APPA President and CEO Sue Kelly in an interview with E&E News. Indeed, there will be 100% cost sharing by the federal government for the first 180 days of emergency work. Long term, however, funding and a return to normal processes will be key watch outs.

Disaster Capitalism

Something I’ve been thinking about recently, particularly in the context of Puerto Rico’s colonial history, is a phenomenon identified by Naomi Klein as “disaster capitalism.” Per Klein, this is the exploitation of crises for corporate gain, often under the guise of relief or reconstruction efforts. For the past 60 years or so, the theory of economic “shock therapy” has been popular among free market proponents as a means to justify opportunistic economic behavior following the “shock” of a large scale disaster, either natural or manmade.

Let’s go back to that editorial in Bloomberg, shall we? “The collapse of the grid, which will cost billions of dollars just to restore, has amplified calls to privatize Prepa.” With those type of calls to action from the news sphere, combined with Trump’s policy predilections and early indicators of how this emergency is being handled (not wrongly, per se, but breaking with convention), it seems clear to me that we are heading down a familiar path. Given what we know about why the grid weakened in the first place (a legacy of colonialist exploitation), furthering that pattern via additional US profiteering seems tacky at best, damaging at worst.

As we continue watching the response to Hurricane Maria unfold, those of us who care about sustainability should be mindful of who we’re enabling to gain figurative power as well as literal. Keep an eye out for where the money’s going, and stay engaged. As much as we want renewable energy, how we get it matters; whatever we do should not come at the cost of additional long term damage to Puerto Rico.

Looking for ways to help with hurricane relief? Check out Carmen’s recommendations here.

Notes From A Queer Engineer is a recurring column with an expected periodicity of 14 days. The subject matter may not be explicitly queer, but the industrial engineer writing it sure is. This is a peek at the notes she’s been doodling in the margins.