BUTCH PLEASE is all about a butch and her adventures in queer masculinity, with dabblings in such topics as gender roles, boy briefs, and aftershave.

Header by Rory Midhani

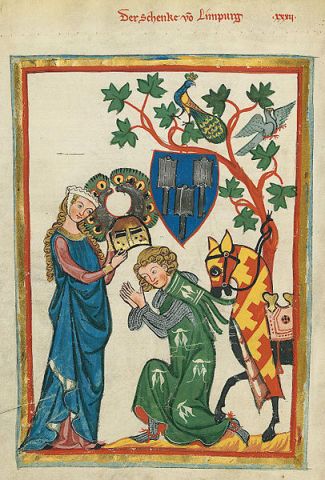

Chivalry comes from the French chevalier, knight, which is in turn derived from the Old French chevalerie, meaning knighthood. I loved knights as a kid, and often played as one. I had sticks I’d carved into swords with my Papa’s old jackknife, and special tokens I’d earned in my imaginary battles, like palm-sized stones made smooth by the Hudson, or the blood-red garnet I chipped from rocks behind the house. These things had magical significance to me, capable of cloaking me from my enemies, or transforming me into an animal, or a boy. With the garnet in the front pocket of my overalls, I’d walk back into the house and pretend I was now a boy knight, unrecognizable to my family. I’d sit down to dinner with my legs crossed wide, wiping my mouth with the back of my hand. If my mother was there, her magic eyes would see through the charm and correct my posture, but if it was just my Nana and Papa, I’d get to stay a magic knight until bathtime. These were perfect days.

I still loved knights in my adolescence, although their trappings were less traditional. Joan of Arc was my confirmation saint, the boy-woman who became a knight. I read a lot of Tamora Pierce, which I’m beginning to realize is a common thread among queer kids. I realized that I didn’t have to be the kind of knight King Arthur called for in order to chase after my own dragons. Perhaps there’s something strange about a working class kid from the mountains adapting such a well-known elite narrative to carry her from one stage of life into the other, but at the time it was essential to how I navigated my little world and its obstacles.

I re-encountered knighthood when I came of age very far from the garnet. I was familiar with chivalry in the sense that it meant boys giving you their jacket when you were cold. I’d never had a boy do that for me, but I assumed that at some point it might happen, since life to a small town adolescent feels very inevitable. My parents started dating when my father was in middle school. My high school peers started getting married in a rash between my freshman and junior year of college. My preteen self was always looking at other people’s narratives and imagining how they would look on me. When I turned 18 and moved away from home and into the arms of other girls, I only then began to realize my narrative was entirely my own.

Like the knights in my stories, I ended up in many harsh battles, and my current armor is as patched and dinged as it will ever be. I also met maidens who granted me special amulets, and awarded kisses with magical powers. I found tokens of strength and endurance in unexpected places and kept going. But queer knighthood is not the same as chivalry, and chivalry is the term I found myself brushing up against, often in tight spaces, when I started to learn how to behave in a relationship, especially one where titles and labels are the lay of the land.

Butch chivalry is a strange jacket to wear, if only because one person calls it flattering where the other says it’s too tight. I’m still not sure where I fit into the butch behavior spectrum, as I know some butch-identified people who swear by the chivalrous treatment of their ladies, and others who eschew it as an anti-feminist habit. I’m a student of our long and suppressed herstory, and scholars love to talk about the ways in which chivalry corrals women like cattle, keeping certain bodies in place while allowing other bodies to control their movements. I’ve seen some queer people who insist on holding doors, and other queers who use their stilettos to step on the feet of the men who do the same. I love them both, but I’m not sure if I can call sides in a concept of gentlemanly behavior that’s much older than any of us.

I say butch chivalry not because the behavior and etiquette specific to queerness is a weight carried only by butches, but because in that same code of conduct, there are certain expectations and roles appropriated to that of the butch. Maybe this is why I only dance around the subject rather than wear it as a badge of honor.

I follow the manners I was taught would make me a kind and decent person, and try to avoid the ones that were enforced to make me “ladylike.” I hold doors because I was taught to hold doors, and I’ll let someone older or less sturdy than me into line. I’ll lift heavy boxes, assemble furniture, and drive you to the hospital in a snowstorm. If this makes me chivalrous, so be it.

I’m concerned by a concept that says we must, as masculine beings, guide feminine beings through the world via pulled out chairs and opened doors, but I also think that courtesy is courtesy, and if I care about you and can make this ridiculously difficult life any easier for you, I will. If I desire you, you won’t just know it in the way I throw down my coat so you can cross puddles, or offer my sweater when there’s a chill. I will reveal that desire in much less “masculine” ways.

When I have a crush on someone, I have a tendency to make them meals, clean their house, finish their chores.* If I could knit, I’d knit them mittens in a shade that matches their eyes, and I’d slip them onto their small hands when I saw their fingers getting chilly pink at the tip. I do everything but tuck them into bed, and I do it with the knowledge that the instinct to take care of someone is a strange one. It can be stifling for the receiving end, to have someone replace certain aspects of your independence. I’m always afraid that my actions will make the other person feel incapacitated, handicapped by my love for them, reduced to a child. Maybe this is because we associate these actions with our parents, our grandparents, people with whom we have very established roles, people that make us feel like we are five again and helpless to the world.

This form of caretaking and crushing is a strange hybrid of the way I was taught to be a woman, and the way I taught myself to be someone who loves women. My parents did not teach me how to take care of a man. I know many of my peers were given careful lessons on how to find a husband, how to make sure he comes home and stays there, but the worst thing my small town parents could imagine for me was an engagement ring from Sears in my second trimester. Not that there is anything wrong with any way we find ourselves slipping through life, but the farthest my parents lived from their birthplace was forty minutes. As a result, they pushed college on me like a wool blanket, inescapable once it was wrapped around me and wet from all the tears I’d cried over not feeling at home in a home where everyone knew my name. As fate would have it, I’ve stomped from one side of the water to the other, and the queer community is often just as small, just as burdened by the fact that we all know each other in one way or another, often in the Biblical sense.

I know I bristle under certain kinds of care, if only because so many parts of my identity are wrapped up in the notion that I cannot ever be in need of help, that I must be a pillar of emotional stability. Knights carried the crest of their family name, as well as the favors of their lady. As a displaced queer, my heralds are my own, but I often wish I had a white handkerchief to tie over the bleeding heart on my arm.

* My roommate is the only exception to this rule, and we share a wonderful bachelor pad with a wifi network named “2butches1cat.” Since I am only working freelance now, I stay at home and do most of the cooking, cleaning, and housemaking duties. I decorate the house and make sure the animals are fed, all while making my hair look impeccable. It’s a balance that works perfectly for us and has earned me the title of “trophy husband.”

Special Note: Autostraddle’s “First Person” personal essays do not necessarily reflect the ideals of Autostraddle or its editors, nor do any First Person writers intend to speak on behalf of anyone other than themselves. First Person writers are simply speaking honestly from their own hearts..

Comments

Your writing is, as ever, beautiful.

Tamora Pierce for the win. When I struggle with things, I ask myself, ‘what would Kel do?’ :)

PS I second Luce, I get all happy when I see a new ‘Butch Please’ tweet!

Tamora Pierce is amazing. Kel, Alanna, Aly, Daine, Beka Cooper- so many fantastic ladies.

I didn’t know this was a gay thing! I adored Tamora Pierce, and devoured her books even after I moved on to much less “young adult” type novels. When she said in an interview Lalasa was gay, when Daja came out, when one of her characters was a trans woman, It seems to make a lot more sense. Oops.

I didn’t know it was a queer thing either, but just looking at this thread, it really was. I’m a trans woman, so I didn’t identify with Alana particularly (I sometimes wonder what impact a novel with a young CAMAB person presenting as female would have had on me), but Pierce’s books were some of my favorites. I was totally unsurprised when I learned that some of Pierce’s later books had gay and trans characters in them. She definitely had queer awareness and even at that age I sensed it.

For years, What Would Alana Do was the unspoken question that spurred endurance whenever I was having an internal whinge about something. I love knowing that I’m not the only one.

Totally! Me too! Kel and Alanna were my heroes growing up.

Someone definitely needs to write a Tamora Pierce appreciation article, or start an open thread. So many feelings!

I honestly can’t believe Tamora Pierce is a queer thing! Trickster’s Choice is one of my all time favorites. Wow

Love Tamora Pierce! Registered with Autostraddle just so I could say this!!

Me too – just got home after a long day of work in bloody London and smiled when I saw the new Butch Please post. Wonderful thoughts, as always. Feel like I´ve been virtually tugged into bed.

I also chose Joan of Ark as my confirmation saint! I chose her because she seemed to have done something and was the most dynamic of the women I had to choose from. And also she had the same name as my recently deceased Grandma. I thought she was cool and if I was going to take an extra name I wanted it to have relevance to me. But, since I have left the catholicism I was brought up in I think it’s very clear that I picked her for all her traits which were not her devotion to God, because that was the thing in all the other saints which I didn’t relate to.

Anyway, I just thought it’d be interesting to see if there are any other queer catholic-born Joan of Arks out there?

As always, loved this column. Keep doing what you’re doing.

i am culturally catholic by virtue of being brought up in it, attending catholic school, still being part of a very catholic family, but I am certainly not a part of the faith anymore (not that catholicism is very concerned with the faith – it often feels so much more like a cultural and social affinity than anything else, especially at the level of catholicism I experience via school and parish).

regardless, i can say that joan of arc is TOTALLY RAD to this day and i chose her because she was a badass warrior, representative of my heritage, and smashed the patriarchy. i will probably give one of my children the middle name of jean or jeanne and hopefully people will realize it is because of my saint’s name and not joan from mad men who is also the love of my life

I like this term “culturally catholic.” I think there are many who fall into this category, especially when that’s how their family identifies or views it as a pillar of their cultural identification. And the observation that it’s not very concerned with the faith: refreshing to see someone say it, even on the internet.

I also like the term culturally catholic. I’m the result of a mix between Polish catholics, Irish catholics and French catholics, which pretty much means a central part of my heritage and family history is wrapped up in the catholic faith, regardless of whether I still belong to that faith.

I briefly considered Joan as my confirmation name too, but then I realized that there were three other women in my immediate family who’d chosen Joan. I share a first name with one of my grandmothers and my middle name is my other grandmother’s first name (and my mom’s middle name), so I really wanted to find a name that belonged to only me. I ended up getting into a fight with our bishop about whether girls can have male confirmation names. That resulted in my having a male confirmation saint and taking a slightly feminized version of his name for my own, which pissed off more people than you’d ever guess.

Sometimes I just want to travel back in time and show my 13 year old self a sign that says “you don’t know it yet, but you’re really really gay, and that’s totally okay”.

Joan’s my confirmation saint. I wear her chain around my neck all the time. And I’ve always described myself as a “holiday Catholic,” as in Christmas and Easter, facile as that may sound.

My Joan is the Joan of George Bernard Shaw, the Joan put before the learned Bishops, the anti-cleric with an answer for everything, come of her singularly brilliant mind. I see her more as a political genius. Proving so many old men incompetent and wrong and telling them so sent her to the flames quicker than anything else.

(Nothing wrong with naming a kid after Joan Harris, either. Just saying.)

I took St Clare because it said on the little flash card thingies that she was the patron saint of television. My already cynical 11 year old brain thought it was ridiculous that a person could be a patron of something not even invented at the time of their death. But also that I really liked TV so if I had to choose one I might as well make my selection in the most trivial and least reverent way possible.

Ironically St Clare was actually a pretty badass feminist role model, for Mediaeval Europe anyway :) But as usual, belittled and constrained by the Church hierarchy.

pretty much the same boat

i’ve referred to my entire familt as ‘cultural catholics’ for years

they like the incense

I knew I was non religious when I made my confirmation but I was forced to by my school. We were allowed to choose generally religious names as well as saints names. I chose Faith, not because of any religious connotation but because I was, and still am, obsessed with Buffy the Vampire Slayer.

I bet this sentiment rings true with a ton of Autostraddle readers- I went to mass for the first time in two years this past Christmas and it was so surreal how it was exactly the same and yet totally different since I don’t take communion anymore. It’s easy not to think about when I’m 3,000 miles away from my hometown, living my own life, but when I’m home I get this weird twinge of missing the community aspect.

Also, while Joan of Arc is a badass heroine, there are some great female saints to choose from. I went with Catherine of Sienne- homegirl ran a hospital and advised kings in the Middle Ages. Kind of a predecessor of another favorite hero of mine, Michelle Obama!

It was a United Methodist Christmas Eve service (two actually, my Grandma’s church and then the church I grew up in), not a Catholic one, but I also had a surreal same-but-not-the same experience last month. Just being in the church building where I spent so much time from childhood through high school (church, sunday school, bible study, youth group, etc) was enough to throw me for a loop, since I and my life have changed so much since then. Glad to know I’m not the only one with this holiday experience.

And Joan of Arc and Tamora Pierce are awesome.

I am an ex-Catholic (but then you never really escape), and Joan of Arc was my patron saint -there was never any competition.

And in regard to the piece as a whole, interesting take. I almost didn’t read it because I have so many feelings about chivalry. I HATE it so much when men tell me to go first or open doors for me because I’m a woman (it’s fine if they do it for everybody). I can’t even express how angry and powerless it makes me feel. However, I have the impulse to do the same thing.

I’m working on making sure my chivalrous impulse is sex- and gender-neutral, and trying to circumvent the rage by proactively telling men they should go first and opening doors for them before they get the chance to do it for me.

I personally use the term ” recovering/recovered catholic,” which seems apt. I realized I didn’t believe early on, and adopted the label “atheist” for myself a few years later, but I still have snippets of it that pop up when I least expect it. My family is very Mexican catholic on both sides, so at least some of the bits are in Spanish? My ex attributed my adoration of candles to my catholic past, but I don’t know if that’s a thing or not. All my friends are queer and thus very very unlikely to identify as catholic, so I have no one to ask.

I have also used the term “recoving catholic” but I feel like I’m finally recovered completely. ;) It’s an entirely different world and life when you’re brought up in the Catholic church… My family is still extremely, extremely Catholic. I left the church at 18 and didn’t go to church for nearly ten years just because Catholicism had turned me off so much. Found the United Church of Christ about a year ago and it’s wonderful and so different from Catholic beliefs yet traditional enough in format that it really feels like church. (I know that is not even the point of this article, but thought I’d throw it out there if anyone is looking/needing/wanting a church.)And they super love them some homos… so there’s that. :)

Aww man I didn’t even realise Joan of Arc was a saint before I was confirmed, or I totally would have chosen her! I think I just thought she was a historical person like Boadicea, but I now realise how horrendously wrong my general historical knowledge is.

For a second I thought that read Bodacea, who my brain then decided was the patron saint of All That Is Bodacious.

I went with St Francis because fuck you I CAN PICK A BOY SAINT IF I WANT

Same! Well except I changed to to Francine to make it work

i’m Lutheran, we don’t do that shit.

Beautiful as always. Appreciate this post, love the way you articulate yourself.

I always love this column. I hold doors for anybody, male or female, young or old. It isn’t meant to be a butch thing for me, in my mind it is just manners. On the same token, I will give my jacket to pretty much anybody I’m with if they need it, even if it means I’ll be a little cold. I want to take care of the people around me. I think some of it is maybe the southern hospitality ingrained in me but I hope regardless none of my behaviors come off as anti-feminist. After all, I’m an equal opportunity gentlequeer.

I totally agree with you!! I do it for the same reasons!!

a Mexican male friend of mine, at the beginning when we just met, felt really strange that a woman opened the door for him. He is used that in Mexico there are still some macho things done and this is one of them!

agreed, I’m femme and aggressively Texan and I like to do everything for everyone just because I have the energy. why the fuck not.

While I’ll be super-polite to people because of my being raised in the Deep South, occasionally I open doors for straight guys I’ve heard being mysogynistic just to make them uncomfortable because making them sort out their “OMG a WOMAN is opening a door for me and I’m a MAN, what do I do?” Crisis seems fitting. Maybe that’s awful of me. Also, while I will offer my jacket to people, my size generally precludes me offering it to men, amd I hate the cold too much to do it for a girl I’m not at least friends with.

i like to hold doors open for guys, especially guys of the more conservative and heteronormative persuasion

It is so amusing to watch them stumble over their gender roles

oooh me too. it’s hysterical and weird how many of them just can’t handle it.

I’ve had guys get weirdly passive aggressive about that! “NO YOU GO FIRST.” *glare* Um, okay?

Oh wait, I didn’t read all these comments, or I wouldn’t have second guessed whether or not me doing the same thing made me awful. Haha.

So there’s a weird line between “chivalry” and “actual useful good manners”, because to be honest, it’s not usually hard to open a door or do some of the myriad of other things that are more /symbolic/ of good intent than they are actually useful.

I don’t have a problem with symbolism – roses, holding doors open, handshakes, rings – and in fact I enjoy embracing it. Because sometimes the best thing to do is to let your partner choose for himself/herself what courtesies they need or want from you, and a token like “holding the door open” /can/ show that you’re open to helping them or doing things for them. It opens the door, so to speak, for other things.

When chivalry is used in that context – as a gesture to show you care about someone, that you’re open and willing to do more should they only ask it – I think it is something that should be embraced.

I also read a lot of knight stories as kids, and to me, they were all metaphors for that attitude. I’ll kill a dragon for you, so you’ll know that if you need me to make you breakfast, I can handle it.

Oh I agree with this so much! When I was a kid the biggest problem I had with traditional “chivalry” is that so often men like my dad or my uncles did very “courteous” but generally useless things like open doors while never helping with the dishes or children. I think that true chivalry takes into account the needs and desires of the other person to actually help them best. Traditional “chivalry” feels very anti-feminist because it relies upon certain proscribed actions that often are more about the gesture (and therefore the man) rather than the needs of the woman.

“I think that true chivalry takes into account the needs and desires of the other person to actually help them best.”

This wins all the awards.

“I’ll kill a dragon for you, so you’ll know that if you need me to make you breakfast, I can handle it.”

I really enjoy this line from your comment. I +1 the entire thing, but this struck me as particularly charming.

I loved this. And I had no idea Tamora Pierce is a queer thing. Add me to the list!

I don’t think it was intended to be; it just evolved that way.

“I follow the manners I was taught would make me a kind and decent person, and try to avoid the ones that were enforced to make me ‘ladylike’ ”

THIS!! I always hold the door open for everyone and give my seat up for someone older than me, man or woman. I burp SOO loudly at the dinner table at my house though! Probably because of years of being told that I would never be able to keep a man with such bad table manners. GOOD THING MY GIRLFRIEND THINKS IT’S HILARIOUS AND CUTE!!

I was taught to be respectful and courteous to ALL people, not just women. However, I do get a distinct pleasure in holding the door for a woman, pulling out her chair, offering her my coat, etc. I feel like I’m the gentleman (gentle queer) my grandfather would have raised, though, when I am chivalrous to all people.

Tamora Pierce was my introduction to feminism when I was 11. Seventeen years later I still kind of want to be Alanna…

I grew up in a small town, so for me most things considered ‘chivalrous” are things that to me are simply common courtesy. I open doors for everyone, give up my seat to those older, say “sir” and “ma’am” and so forth. To everyone, regardless of gender. . .

And you know I like a girl when I start showing off. . . It’s a strange impulse, like I have to convince her I really am a cool person.

is femme chivalry a thing? can we make it a thing? or is that just ‘good manners’? (or maybe just being overly southern.)

I was going to suggest exactly this! It’s probably just good manners slash being a nice person, but who knows.

I deeply appreciate ladies that are chivalrous and show emotion, and let me take care of them back (i.e. bois with their hearts on their sleeves.) You, like your writing, are lovely. c:

“…I also think that courtesy is courtesy, and if I care about you and can make this ridiculously difficult life any easier for you, I will.”

This is beautiful. I love this series. It makes me think and articulates feelings I have that I haven’t found the words for. Thank you for writing.

Chivalry from another woman, especially when she’s already shown that she respects me and she’s not trying to control or coddle me, is fantastic. That may just be my fantasy nerd side, (yes, I have nearly every Tamora Pierce book and have associated with Joan of Arc since I was 9) the little girl who used to dream of adventuring with a hot knight, who used to watch “Camelot” endlessly and would walk around saying “I *never* find chivalry tedious!”, but it’s true. If you identify with knights and chivalry and combine it with respect and service, I say be proud. I’m sure there are a lot of girls who would love it if you wrapped your coat around her shoulders.

This is the first time I’ve ever heard chivalry described so accurately, that it has the potential to take away our independence and make us feel like five-year-olds. For years I’ve rejected chivalry, if only on the pretense that it’s anti-feminist, but the reality is that I love it. I love feeling like someone cares about me, and I love that I can give that feeling to others.

But most of all, I look forward to these Butch Please posts alllll the time. Your writing is beautiful, Kate.

“If I could knit, I’d knit them mittens in a shade that matches their eyes, and I’d slip them onto their small hands when I saw their fingers getting chilly pink at the tip.”

asdfkjashdfkjehif

I actually teared up a little at that part

this is so beautiful and gives me nice feelings

“My preteen self was always looking at other people’s narratives and imagining how they would look on me. When I turned 18 and moved away from home and into the arms of other girls, I only then began to realize my narrative was entirely my own.”

This punched me in the gut because I relate to it to a ridiculous level. I’m really just now beginning to shake off that habit of trying to squeeze into those narratives. Accepting that they just will not fit no matter how hard I try has been a hard lesson to learn.

No idea Tamora Pierce books constituted as a queer symbol. Might be time to give those a re-read, all of them! They have their own shelf in my closet, a shrine to escapism and strength.

As always, thank you for your posts. Lovely to read all these thoughts and feelings articulated in such a way that a lot of different people can relate. Personally, I can handle plenty of courtesies but the one thing that my awkward self freaks out over is the door opening, regardless of gender. It breaks the flow; I’m walking to a destination and then someone stops to open a door for me. Not only do I have to have a micro-interaction, if I’m too far away I have to alter my pace to get there. What was the point? I know, tiny, useless thing to worry about but it’s definitely a thing for me, haha.

As usual Kate, you’ve written a truly beautiful piece. I’m always in awe of your powerful metaphors and analogies. I especially loved this following line:

“knights carried the crest of their family name, as well as the favors of their lady. As a displaced queer, my heralds are my own, but I often wish I had a white handkerchief to tie over the bleeding heart on my arm.”

It’s also rather funny that I came upon this article, as I’m currently working on a fantasy novel, which includes a lesbian knight and princess. I’m in the process on working on the dynamics of their relationship and its confusing, because I keep giving them rigid, heterosexual-esque roles (ex. the princess being a passive damsel in distress, the knight being an active hero) While I do want them to have that old school “butch/femme” thing going on, I also want them to be equals, as well as avoid making them cookie cutter stereotypes. I also wrote an essay not that long ago about how when i was a child, I would often create female characters who wanted to break out of their assigned roles. For example, one of my characters was princess who longed to be a hero instead. I also enjoyed pretending to be a warrior princess (thank you Xena, lol). It’s funny though, when I look back on my childhood, I discover a lot of seemingly queer ideas, thoughts, etc.

Anyway, you never fail to find a way to make something so specific (butch identity) so universal. I always feel like there’s some common thread in your AS pieces that I (and others) can identify with and you express yourself incredibly well, so thank you for that.

“It’s funny though, when I look back on my childhood, I discover a lot of seemingly queer ideas, thoughts, etc.”

UH HUH

Honestly, my last girlfriend was femme, and though I’m much more boyish than butch I was still more masculine than her, so we played at chivalry/traditional gender roles. Like opening doors for her or letting her cook dinner for me in her frilly apron or giving her my jacket. But we both knew we weren’t serious about it, because she would open jars for me and she was the one who ordered for both of us when we went out and I took much longer on my hair than she ever did. (My bangs are very important to me!) and we did all this without batting an eye. But it was fun to “play house” a little bit, which is usually how I feel about chivalry personally. As something to play with cause it’s cute and fun but also not to be taken too seriously.

I, too, think some things are just good manners… holding doors, letting people have your chair, etc. And like many who posted on here, if it’s something that is being offered to everyone, I think it’s great. But if it’s something being done by a man because I’m a woman, I am not impressed. I plan to raise my kids someday, whether they be male or female, to do things like open doors for other other people and other “chivalrous” acts because I think it’s about respect and kindness, not gender roles and expectations. Not everyone feels that way, which is why I need a split second to look at someone to try to guess their intentions. (A lot of places have two sets of doors. If a stranger dude holds open the door and insists I go first, I will… and then I will open the next door and insist he go first. Fair is fair.)

I love this series, but this piece really struck my fantasy-reading heart. And this:

“Like the knights in my stories, I ended up in many harsh battles, and my current armor is as patched and dinged as it will ever be. I also met maidens who granted me special amulets, and awarded kisses with magical powers. I found tokens of strength and endurance in unexpected places and kept going.”

This how I am going to picture you forever. Leaning against a big old tree, monster dead nearby, wiping its guts off of your sword with a little smirk. The cords and chains of those amulets barely visible, the amulets themselves hidden (secret) under your breastplate. Your armor is not shining by any means (is that rust or a faded lipstick kiss on your helmet?) but your soul, oh, *that* is shining bright as the sun.

I enjoy everything you write but this one particularly hits home.

I always take care of the people I care about, sometimes to a ridiculous extent. I can’t tell you how may times I have had to preface my actions with “I know you are fully capable of doing doing X but please just let me do it because it’s cold/hot/heavy/unpleasant”

My best friend recently vetoed a potential date based on “I don’t think she is the type of girl that will let you take care of her” haha

Your writing is just as fantastic as it always is, and I relate so hard to the knight and caretaker thing, despite not being especially butch, really.

And, you guys. Those of you who read Tamora Pierce and wanted to be knights and loved girls with swords? You probably need to get your hands on some Elizabeth Moon books. The Deed of Paksenarrion, especially, and the sequels (disclaimer, I haven’t finished Kings of the North yet, but I’m pretty sure it will keep being awesome). And then you can pretend to be Paks, or Dorrin Verrakai, and your life will probably be a little bit better. Anyway that’s how it worked for me.

You’ve captured my entire childhood and my entire being within one beautiful article.

I’ve never understood women who get worked up over someone holding a door open for them.

Probably this is partly because I’m naturally lazy, so anyone who wants to open a door, hold a door, or cut a hole in a wall so I can amble on through is quite welcome to do so, regardless of their gender or gender identity.

But also, just because someone’s holding a door for you, doesn’t automatically mean they’re holding it for you because they perceive you to be female/feminine/weak etc. Maybe they’re just naturally polite and hold doors open for everyone, you just haven’t had the chance to witness them doing this for someone they perceive to be male/masculine.

I was just saying something similar to my mum, that I realised I was the only girl working at the restaurant tonight and she asked if the guys there were nice to me, I was telling her how they always offered to carry heavy things for me and even though Im perfectly capable of doing it myself, I usually accept out of sheer laziness >>

I do open doors and such for people though, and I’m usually the spider catcher whenever the need arises, and I’m proud of these things coinciding with my femmeness.

This is probably the best article I have read in a long time. Love the way how you wrote, as if you were reliving that moment while writing this. Just simply amazing. But, I do have a couple of questions. Would chivalry also apply to cowboys/ good gunslingers? And the second question is obvious, why or why not?

Kate, write a book please. It doesn’t matter what it’s about. Thanks.

Kate, your thoughts on chivalry are exactly how I view it. My girl calls me chivalrous because I’ll pull her seat out for her, hold the cab door open for her, take her coat, open the door etc. I care about her, I care that her jacket isn’t closed when it’s windy, I want to make sure as you say, to make life easier for her. I was taught from a very early age to shake hands, hold the door open and I intend to enact these old school manners, which I have learned from my old school parents. My ways are not an attack on a person’s ability to take care of themselves, that is not my attention at all. Like you, I view it as a courtesy, but also respect for the other person.

Beautiful writing as usual and I always get excited when I see a new article from you! :)

We had the same confirmation saint too! I was and still am obsessed with Jeanne d’Arc!

I love this. I struggled HARD with chivalry when I was trying to be straight. I loathed it. I viewed hating it as a sign of my being an independent woman, and I didn’t need a man to take care of me etc. The reality is that I couldn’t deal with their chivalry because I couldn’t deal with them caring about me, I couldn’t deal with men having emotions for me, because I couldn’t return it. Chivalry is a sign that someone cares about you.

Now that I have come out and am comfortable with being gay, what I’ve found has been a shock to the system – I LOVE chivalry. Those same actions that felt cloying and claustrophobic and threatened my sense of independence with men now make me feel loved and cared for. The difference is that with women, I can genuinely give appreciation and thanks for her acts of chivalry. I nuzzle her and hug and kiss her and then in turn take care of her in my own femme way.

It’s wonderful to finally read my thoughts verbalized in coherent and a ‘that makes sense’ kind of way. People are always kind of amused because of my “chivalry”, but (as stated above) when you care about someone (and not even be necessarily in love) it’s only natural to show it in your actions. And if that combined with a well developed sense of politeness is called chivalry, well then I’m guilty as charged.

I do believe that there is a difference between the kind of care that forces people on the receiving end in a lesser position and true chivalry. No matter you are a man or a woman, the intention you have decides whether you’re a patronizing pig or a knight. If you’re just holding doors and doing stuff like that to impress or because you think that makes you seem like the bigger person, sorry but then you’re a patronizing pig in my opinion. Opposed to people who do it because they genuinely care.

To bore everyone with a bit of history: Chivalry in its original form (medieval style) existed because women had a higher position in society and men were thought to properly respect the castles mistress. So the true chivalry is respecting a woman in all that she is. Chivalry used in any other context or way, stops being chivalry and becomes patronizing.

I love this so much

And I have such a crush on Kate.. *Le Sigh*

I really loved this article. It made me feel a lot better for myself. Thank you for sharing it <3

I truely enjoyed,reading your journey of growth and realisation. the world and its fears is at times a hostile place for a maturing butch. but we must be who we are,cos in that our path gets illuminated…the ways in which we love,and show love is diverse,but ive also noticed that feminine woman value,care that compliments their more feminine ways…thanx for expresing,much appreciated.