BUTCH PLEASE is all about a butch and her adventures in queer masculinity, with dabblings in such topics as gender roles, boy briefs, and aftershave.

Header by Rory Midhani

I cut my hair about twice a month, sometimes more. My hair grows faster than I can usually keep up, so I’ve become well-acquainted with the kitchen floor buzz from a drunk best friend. Now that I’m an “adult” with an “adult career path,” I get my hair cut at a salon, which feels like a mature life decision even if it’s only about fifteen bucks a cut. I show them photos on my phone of schoolboys in the 1930s, or Justin Bieber. Usually Justin Bieber. And I say, make my hair look like Justin Bieber, but gayer and more kind-natured.

That post-haircut feeling is irreplaceable. My neck may feel like a bed of red ants, and there may be enough hair on my face to stock a drag king for a year, but I feel like a million bucks. My hair reflects the way I feel inside. My hair is the way I wanted to cut it for years and years and years, and that feels goshdarn great.

When I was a tiny Catholic schoolgirl, one of my teachers said that short hair was not ladylike, and little girls with short hair would grow up to have bad manners and skinned knees. And an adolescent me heard that girls with short hair did gross things with other girls, and they were ugly and mannish and I shouldn’t want to be like them. Cutting your hair off was a “big deal.” In movies and books, it usually came with a psychotic break or a huge life change or a sign that the character meant business. Well, I mean business, even if it’s the kind of business that is conducted by buying a lot of short sleeved button-ups and being knocked over by intense emotions.

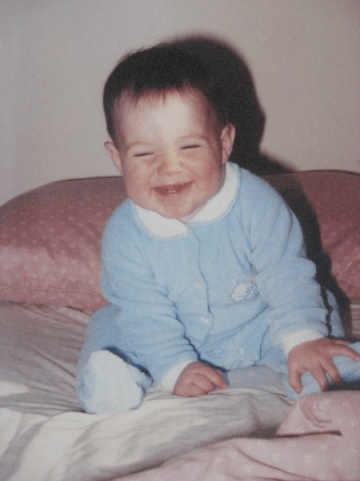

I was born with a full head of hair. Thick black hair, actually, and according to family lore, the first thing my grandfather said when he saw me was, “Damn, it looks like he’s got a bear up there.” ‘He,’ because until the moment my slick little baby body was fully exposed, all the doctors and old wives had said that I was going to be a boy. So sure were they of my gender that they had a blue hospital onesie and blanket ready in preparation. The nurse had to go get a bow for my hair so they’d know the difference when they went to look for me in the Special Needs Unit. A tiny pink bow clipped to my brand new hair, and bam! Gender.

My hair was grown out for the next five years. My dad was given the task of braiding it every morning, but by the afternoon it was out of its well-meaning plaits and flying around my head. My hair was thick, coarse, and usually a tangled mess. I hated combing my hair because there were always knots, so the process was more of a punishment than anything. I avoided hairbrushes, and since I usually ran outside to play immediately following my baths, any effort to detangle was moot in a heartbeat. Apparently my hair was very compliment-worthy, and my parents were always hearing what beautiful hair their daughter had.

I got my first haircut at five not because I had any interest in a shorter style, but because it would be much easier for my parents than the daily ritual of wrangling me into a chair and attempting to get me to sit still long enough to detangle my wild mess. I had a pageboy bob to go with my new plaid uniform. I spent the next fifteen years growing my hair out at various lengths, only sometimes trimming it to my shoulders.

When I was ten years old, a lady in a pink dress looked me over and told me that my hair was my best feature. Don’t let her cut it, she said to my mother. I had those words tucked in between my ribs for years. If I got rid of my best feature, would I have any worth? She hadn’t said anything about my pimply face or my lack of breasts or my sticky-out hips, so she must have known the same thing I’d told myself: that they were ugly, and something to be hidden away, erased if possible. Boys didn’t like me, and people didn’t tell me I was pretty. I had to keep my hair long, or I’d be all the things I secretly thought to be true.

When I first came out, I kept my hair as it was. I didn’t cut it, but I thought about cutting it. I thought about cutting it a lot. But I did not cut it. I felt like people might be more accepting of my queerness if I wasn’t *that* queer, if it was one small facet of my personality that you’d never know unless you asked. I felt like it was more comforting to my parents if I still looked like their old daughter. I might be a lesbian, I wanted to say, and you might not like that about me, but I still look like a “normal” girl. I’m still the girl you wanted me to be, the one who wears dresses and gets good grades and doesn’t fuck up. I know you think that this queer thing is part of fucking up. It might be harder to love me now, but I’m trying to make it easier for you anyway.

My family was not the only reason I hesitated to cut my hair. I was already losing friends and receiving negative reactions to my coming out, so I thought that the less I changed about myself, the less likely people were to interpret my new queerness as a bad thing. Looking back now, it only makes me sad to think of how much queer people are asked to hide and shrink away and accommodate everyone else in an attempt to feel a little of the love that society tells them they don’t deserve. Coming out is planned around other people, and based on the least amount of negative impact. Queer issues aren’t brought up around family or loved ones so as to not make them uncomfortable. Complaining in the workplace isn’t done as often as it should be, for fear of making drama or being pigeonholed. I have done these things, or my friends have done these things, or someone we know has done these things. We shouldn’t have to do these things, but we do.

Now, hair is part of my queer ritual. I cut my hair off when I was twenty. It was representative of a lot of major changes in my life, including a final departure from my worst year of depression, anxiety, and self-harm. The partner I had at the time hadn’t been jazzed about my new style, as she claimed that it threatened her masculinity. Out of a combined fear of her words and my own perceived ugliness, my first short hair cut was on the feminine side of things. I also hadn’t known how to explain to the hairdresser that I wanted a short cut like a boy, not like a girl, so I’d nodded quickly when she’d finished and said everything was fine. Because it was a feminine cut, my mother seemed to be okay with this new style. I was still wearing “girl” clothes. I was still not obviously queer. I was still easier to love.

When I was a senior in college, my best friend and I started cutting each other’s hair. We were not always sober, but the ability to shave off whole patches of our heads in mismatched ways was one of the most empowering things I’ve ever done with my body. The fact that my hair, unquestionably queer and strange and masculine, was now such a huge part of my self-care was monumental. I am more than willing to spend an hour on my hair now. I have at least three hair products with me at all times. I always have a comb, and it is frequently employed to fix any strays. I have had multiple styles over the last two years, and I’ve loved them all. This happiness involving my hair is tied in part to being unapologetically recognized as queer, but even more, it’s tied to being in control of how I look, how I present, and feeling comfortable enough to do with my body as I please.

A very special note: To my long-haired butches, you’re damn gorgeous, too, and I may be joining you. I’ve been told by many that my jawline and cheekbones were too big and unsuitable for long hair, but I’m in that place where I’m sick of people telling other people how to make their body smaller. Masculinity doesn’t mean short hair, and you’re living proof. Butches are butches no matter their hair, their style, the way they walk or talk or fuck or love. If you say you’re a butch, you’re a butch, baby, and you’re butch enough. Don’t let anyone or anything tell you otherwise.

Comments

your first short haircut is a cut I would love to rock but I don’t have the confidence to go that short… yet. one day this baby gay may just muster to courage to do it. Thanks as always Kate for your words.

I love you … in that totally platonic and non- committal sort of way.

I agree 1000%. I may save that photo for inspiration, if that’s cool with you, Kate.

That is a really nice hair cut. I’ve been slowly cutting my hair shorter over the past year, and I hope to ultimately have a style that looks sort of like that.

I wanted to cut my hair for a good ten years when I was little. My parents wouldn’t let me, because, and I quote, “hair is a woman’s glory.” I think they told me that at least every other day. There were other reasons, or First Nation and Mexican cultures, but mostly religion. So I tucked my hair into a ball cap and tried to pass as a boy like that, and I did.

When I was twelve, I took scissors and then my dad’s razor to my long, beautiful hair. The only time my parents were more angry at me than that situation was when I came out to them. They made me wear girly hats for a good year until my hair looked to be an acceptable length.

And now, at almost twenty-one, I haven’t cut my hair short since. Now that I’m free of a patriarchal, oppressive girlhood, I don’t see my hair as something that holds me back anymore. It’s not associated in my mind with something lesser, weaker. And I’ve embraced it, like the rest of my femaleness.

It’s fascinating just how much is tied into hair. Thanks for this. It’s good to know I wasn’t the only one with so many feelings about my feminine hair.

Also: you have FANTASTIC hair, long or short.

Thank you so much for this! I have so many hair feelings that it’s hard to make them be words.

The first haircut was liberation.

“The partner I had at the time hadn’t been jazzed about my new style, as she claimed that it threatened her masculinity.” Upon reading this I made a wtf-that-makes-no-sense slash angry-at-this-former-partner face at the computer that I wish you could have seen.

Also, your cheekbones and jawline are wonderful! Screw them.

Fuck yeah! Happy Pride!!!

Cutting my hair short was SO freeing! I felt like I was finally showing everyone else what I felt inside for so long. I too kept my hair long for awhile because people said it was my best feature. I got compliments almost every day about it, which I appreciated but also felt kind of weird about since inside I really wanted my hair short. When I started getting compared to Taylor Swift, I got to a breaking point. I know some people like her and that’s fine, but I hated people saying I looked like her. The way I saw and still see her and the way I wanted and still want myself to look are so different. Off went the hair and now I rock some short curls just the way I like them. :)

I’m totally thinking of getting my hair cut again. Right now my hair is shoulder length and makes me feel a little bit like a rockstar.

Whenever I tell people that I used to be mistaken for a boy on a daily basis with short hair, they seem really upset and tell me: “No way! You look so feminine! Don’t let anyone take that away from you. You’re a gorgeous woman.” That makes me feel really anxious. I don’t want people to perceive me as a “gorgeous woman”. I like people to see me as the funny, smart, down-to-earth person that I feel I am. (So NOT feminine!)

At the same time I work at a bar – and drunk guys give better tips, if you don’t look like a man hating, pussy eating Diesel Dyke, so…

What a great article! It always astonishes me that your articles, even the ones that are about seemingly trivial things like a new haircut, always touches me and teaches me something new about life, and all the small and big choices we have to make to become who we really are. Your writing is really great! And your new haircut too, obviously :)

“I felt like it was more comforting to my parents if I still looked like their old daughter. I might be a lesbian, I wanted to say, and you might not like that about me, but I still look like a “normal” girl.”

This made me laugh, thinking of when I came out to my mom, having already gotten an undercut, I was told “Don’t shave any more of your head, you look like enough of a lesbian as it is” Cheers mam, thanks for your support.

I had to resort to Cutting My Own Hair because it was(and still is) much easier for me to cut on the back of my head than talk to strangers, but somebody told me that was kinda hot? in a “change your own oil” way, so there’s that?

There was a certain terror in walking up to the VERY feminine hair dresser and saying “I want it short, no really short. No, like this.” And having that ‘oh!’ look come over her face. It took everything I had that day.

I still remember having to show the hairdresser in the small town I’m from, a friend’s facebook profile because she legit didn’t know what I was talking about. Dyke chop should just be something they know about.

I have finally found a hairdresser I really like. I’ve been to her twice- she uses the barbers razor to shave the sides and humours me on my colour indecision. It’s early days yet and I don’t want to put this fledgling relationship under pressure but I think, I’m ready to come out to my hairdresser!

When I first cut my hair short, I mainly chose the stylist because I could just tell him I wanted it cut like his hair but dykier and he understood what I meant.

Unfortunately, I have to find a new hairdresser and I’m dreading it.

I finally managed to find a queer hairstylist and the heavens opened up and angels sang and it was a beautiful, wonderful thing and my hair finally became what I wanted it to be.

She’s also gorgeous and delightful and I now get my hair cut way, way more often than is necessary.

I find hair salons kind of terrifying and I can’t put my finger on why, I just always feel not something enough and I’m not sure what that is. I have long hair, I’m on the feminine side. But I don’t blow dry or use products at all, I’m not super fashionable, I don’t often wear make-up, I don’t shave… I just feel like there some measure of trying or artifice that I’m not meeting and I honestly just feel anxious the entire time. I walk past barber shops and stare longingly in… there’s something cozy and nostalgic and laidback about their decor and how I imagine the banter to be. But they wouldn’t know what to do with long hair.

I was kinda the opposite, I got my hair cut as short as I dared when I came out and changed my clothes to try and be read gayer, it’s only really in the last year that I’ve been like fuck it, I’m femme, growing my hair out again and wearing ALL THE DRESSES! The money I save on not getting my hair cut is instantly blown on pretty clothes. So yeah eff other people and look the way that makes you happy <3

(Also Kate you’re totally giving off Keira Knightley vibes in your first haircut pic, I think its the lip thing. You guys know that lip thing, you stare at Keira Knightley’s lips all the time. Not just me.)

I had early-adolescent pants-feelings about Keira Knightley in Pirates of the Caribbean and that lip thing she does :D

I’d like to join this party of pants-feelings about Keira Knightly in Pirates and also nearly every other movie I saw of her as a teen.

Definitely a complete liberation for many. On the femmier side of things, I have to say that I felt a similar but different pressure while in the throes of my coming out. The societal pressure to be immediately identified as one thing or the ‘other’ very nearly had me shaving bits of my hair off- something that my regualr self would never do.

I also had to got through the punishment of brushing hair out as a kid. It sucked. But then I learned to manage it. I was okay with long hair for a while but then I really wanted it short. I’ve kept it short ever since and will probably always have it short but every now and again I miss the feeling of braiding my wet hair after a shower and then waking up the next morning and unbraiding it and still having moist wavy hair.

I know exactly how I want my hair(patterned cornrows in the first fourth and fro in the back). Unlike how I have my hair now, I think it’ll work whether im in a dress or clothes from the boys dept. But idk! I’ve worn my hair out before and lets just say im not a fan of ppl touching my hair (w/o asking). This however:

“My hair is the way I wanted to cut it for years and years and years, and that feels goshdarn great.”

Makes me want to give it a go again!

Also, for any of you that, like me, find it hard to explain what they want to the hairdresser, then end up super upset at the results: I am going to impart the greatest piece of new-hair wisdom I every received. The bald taxi driver that collected me outside the hairdressers after one such visit, said “did you get your hair done?” I burst into tears. He sighed and said really patiently, like somebody that has had this conversation about a hundred times before: “Listen love, I’ve a wife and three daughters. I can guarantee you that once you’ve gone home and done your own thing with it and used your own stuff on it, you’ll feel a lot better about it.”

And that haircut went on to save spring break. No but seriously 4 hours, 2 cries a ghd and a slew of compliments later, I fricking loved it. So stay calm. Time heals. Hair grows.

Y’all know how salons have cutesy-poo names? My all time fave was one I saw in Tucson: It’ll Grow Out.

But, really. Go home and live with it for a day. You may like it. But then again, maybe you won’t. It’ll grow out.

The best-worst salon name seems to be something they’re all competing for where I’m from. “Vanity Hair” is definitely up there. But the best of them has to be… “Curl Up and Dye” which never fails to crack me up

Everyone in my immediate family “loved my long hair so much”, so I so often heard “don’t cut it, ever!”, “your hair is your best feature”, “look at those gorgeous curls!”, and such. I was never allowed to cut it off, and mentions of shorter hair were met with heavy silences of disapproval.

On my third day at university, I put my hair in a damned ponytail, cut it with an exacto knife, and donated that mass of hair to a charity. I’ve never had long hair since, and I still hear complaints from my family about not being feminine, and that I’m “just going through a phase”. Every year I cut my hair shorter. It is such a big thing to be free do to what you want to your body.

You do you, and fuck what everyone else says.

The best thing about cutting my hair short (besides how much more I love having it this way) is that now I do so much more with it and try things. I’ve more hairstyles in the past three years than I did in the previous 15 or 20 years. My hair grows freakishly fast so I’ll go through multiple styles between cuts.

My first short haircut was when I was 6 years old and it was a gift from my pragmatic paternal grandfather. He was this big scary man with a deep voice and a huge, hard, big belly. I was terrified of this man. My hair was long and wavy and would tie itself into knots. After witnessing my mother “detangle” my hair which involved me crying my eyes out, Grandpa took me to his barber the next week and cut it all off. HIS BARBER! Love that man! Granted this started the era of girls running from public restrooms screaming about a boy whenever I entered -but it was still AWESOME.

I think you look pretty damn hot with short hair. Just saying….

I’ve always had my hair pretty short just because i didn’t want to care of long hair. Luckily my family was pretty much “it’s your hair” about it, although my mom did give me home perms to “tame” my already natural curls.

It was hard to find people willing to cut my hair short enough/in a style I wanted….until I joined the Army. It was much easier then, because the hair dressers/barbers were somewhat used to women who wanted shorter and even masculine styles. Even after I left the Army, I stayed in the same area, so i could still get the cuts I wanted.

Now it’s even easier, because my girlfriend cuts it for me. She got tired of me putting off haircuts until my hair was too unruly (due to my hatred of talking to even understanding hairdressers…)

When I chopped my hair off I felt free. Getting rid of my hair helped me gain confidence in myself. My hair is currently in the shape that it has always wanted to be in.

I had short hair from when I was little (before I can remember) until I was around 7 or 8. I began playing ice hockey (still a stereotypically “boy sport”) with that hair. My scraped knees and bad manners continued loonnnnggg after my hair grew out though. Thank g0d.

Now that I think about it, I probably should have just gone with a mullet. Hockey players have mullets right? At least that’s what everyone who doesn’t play hockey tells me…

“…threatened her masculinity…” <– Anyone that says anything like this, ever, already feels threatened. For no good reason. Just because they're insecure. And deserves a verbal bitch slap.

I am in a weird hair phase right now. When I was young it was super long. But, for over 10 years now I've had it super short. And as much as I like it and am comfortable like that, I got super bored with it. It was so short I had no real choice but to grow it out some in order to try something new. The problem is, I can't find any style I like. I just want something kinda andro and something that can do more than one style depending on my mood, but that is easy to style cause I don't want to waste time on it, and all the hair pics I've seen so far I don't like. Frustrating.

I get my hair cut about every 8 weeks, because I can’t afford more often and it only grows about an inch in that amount of time. And yes, there is nothing like that sensation of “OMG I look like me again!”

Just popping in to rep for the long haired of us out there. I can’t tell you how hard it is to explain why I keep my hair long but refuse to style it in a decidedly feminine way. For me, my long hair is one of the most masculine parts of my presentation. Hair feelings x1000000.

Honestly, worse than the obnoxious comments from straight family and friends are the comments coming from within our community. There’s nothing like being told that your hair looks like someone is forcing you to keep it long so that you don’t look too gay.

While I always watched Top Model makeovers and rolled my eyes at the tears shed for hair, I kinda get it now, that there is far more to hair and I really enjoyed all the things you said, all the things you said, about hair (that was an attempt to inject TATU into a comment).

It made me think..

I got the “dyke chop” a couple of years ago after I had sorted through a lifetime of having internalised the idea that lezzys with short hair were undesirable and just “trying to be men.” Changing my hair seemed to constitute a reassertion of agency over my body and it felt really fucking good. The politics of hair though and gender presentation espec in the context of queerness became hella apparent. It really depended on social environment, but I’d say 60% of the time when I had long hair and fit the “femme” mold, I was read as “ethnic” or non-white. Howevs, since I cut my hair, there seems to be no racial ambiguity and I’m seen as white. Actually, I suppose its more accurate to say that the more “visibly queer” I’ve become the more by racial/ethnic identity has been subsumed by my sexuality. I think through this a lot, and I suppose femme invisiblity aka the assumption that women with “feminine” gender presentations are hetro plays into it but is entangled with the assumption that PoCs are also auto-hetro. Like you can only rep one identity, can only be reducible to one aspect of the self, and if you’re a super hot product of miscegenation that has a racially ambiguity to you, the puzzle of your racial and ethnic identity is solved by looking “like a queer.”

I think about this a lot, how astounding it is that a haircut can reorient public perception of an individual (Miley Cyrus WUTUP), and often get lost in my words and cannot really string together a coherent sentence about all of my feeelings (not that the above can necessarily be filed under COHERENT). So thank you for writing a piece that so seamlessly helped to frame me working through my hair issues. This piece = hairapy for real

Kade, I love the fact that the first and last photos of you here have something in common. Menswear. Check. Short hair? Check. Face that says “zero fucks given” Check.

Turns out baby Kate was a bit of a MOC badass too! :p

Great article Kate. Way to articulate everything I’ve ever wanted to say on the subject.

I’ve been cutting my own hair on and off for about 10 years, and cutting other people’s hair for about 3. I’m pretty darn good at it too, although I’m basing that on the fact that I’ve never made anyone cry and people keep asking me to cut their hair.

And now, having just spent years of my life earning a Masters degree in a field I don’t want to work in because I didn’t know what to do with my life, I’m seriously considering becoming a barber.

Because I love cutting people’s hair. Because I love being able to help others be who they want to be, to feel the same thrill I felt when I stood in front of the mirror at 15 and cut off hanks of my long hair with shaking hands and blunt scissors. It seems like such a trivial thing, but it really isn’t. It’s agency, and it’s fun and (as my first buzz cut taught me) it can be a fantastic lesson in humility.

And I certainly don’t mean to derail this thread, but does anyone else do this professionally (feel free to PM me)? Is it still fun if you work in a salon, rather than in your kitchen drinking wine?

I don’t cut hair professionally, but my former partner has been doing it as a career for seven or eight years now and loves it. Yeah, she has days where it’s not super fun, but she loves seeing people look at themselves in the mirror and feel like new people. And it’s very artistic and creative at the same time, which is great. And, depending on where you live and work, being queer in the beauty industry is usually pretty well-accepted. Whether or not you’re out to your clients, they just accept that hairstylists are kind of alternative and are basically beauty rockstars. Which is rad.

Also, dating a queer hairstylist is a great idea for queer hair development and we still have an awesome friendship in which she continues to make my hair look more and more boyish as I get butcher.

Hmm, this sounds positive. As for being out to other people… Everyone knows I’m gay. People knew I was gay even when I thought I was straight. There doesn’t seem to be a whole lot I can do about that.

I’m glad you’re still in good terms with your former partner, and that you’re still able to have her cut your hair. Tbh, I really wish I knew someone who was willing to cut my hair for free… Actually that’s not entirely true, I know plenty of people who would cut my hair, but none who could do so to my liking.

Well fuckit, I’m doing this.

I’ve been thinking about cutting my hair short for quite some time but was too afraid to, and I don’t know why but this piece was like the kick in the butt I needed to finally take the plunge – next week will be the end of my exams and my birthday so this seems like the perfect time. I’m tired of wasting money on getting the shortest bob cut possible, feeling kinda okay about my hair for two weeks and then ruthlessly tying and pining it back up because it makes me feel like shit when it grows back – and I don’t care if it visually outs me or makes my face look like an amorphous blob because I don’t have much going on in the jawline and cheekbones department. Thanks Kate (but also screw your perfect jawline ’cause that’s just not fair).

If I may make one suggestion? Bring pictures of what you want. It really helped with mine.

I totally feel you on the shortest bob cut for years thing AND the amorphous blob face thing. That was the reason I waited so long to cut my hair. But when I finally got it done there were no regrets. I’m excited for you! You are going to look and feel awesome :))

And I second bringing pictures of what you want, I brought quite an extensive collection of Tegan pictures so the hair stylist could see the cut I wanted from literally every angle haha. I’m sure I seemed very neurotic.

Kate, ALL of your looks have been gorgeous, from fuzzy baby, to femmy little girl, to totally butch. Maybe that’s because YOU are gorgeous.

I’ve always treated my hair like art; I love doing different things with it color and style-wise. Soon to be ex has PTSD, though, and has gotten upset over anything “non-standard” because “it draws attention to us and I can’t handle people staring at me.” I get that, and have been totally compliant out of respect and support for ex. Ex moves out at the end of the week, and I’ve already shaved the sides and back. I’m so ready to let my hair be my hair again! Thanks for expressing just how great it is to have your hair cut the way you want!

Thank you so much for this. I can connect with so many of these feelings. Screw society and the norm!

I just see a dope hairstyle for a chick. Short != Butch

LHBs make me weak in the knees

Mad props for the shoutout to long-haired butches. My masculinity should not be erased by the fact that I don’t want to cut off my hair, even though I often feel as though I’m not allowed to claim butch identity with the hairstyle I’m rocking now. It creates this ridiculous situation where I feel as though I have to exaggerate other aspects of my appearance and mannerisms in queer spaces to be read as ‘butch enough’.

Thank you, Kate, for this article. It really resonated with me.

I cut my hair short for the first time last year, it was incredible. I remember watching it all fall away, and I finally recognized myself in the mirror. It was like seeing my self in the mirror for the first time in my life.

Absolutely incredible!

I had been in constant relationships for years before then and there had always been someone who liked the way I looked so I never cut it cause I was afraid they wouldn’t like how I looked anymore.

It sounds a bit like I’m exaggerating but it really changed my life. I came out and started talking to people about my gender and it was incredible.

wouldn’t take it back for the world

So I’m not butch or masculine of center really (more center of center) and my short hair is a big part of my self care, too. About a year and a half ago I was going through a difficult time at work (just started a new job and some people thought bullying was fun), and towards the end of it I decided to take the plunge and cut off all my hair for the first time since that ill-fated dyke chop when I was 18. And good GOD was it liberating!

I joke that my short hair makes me more of a girl than my long hair ever did – long hair got left to its own devices or put in a ponytail. Now I use a hair dryer and two different products.

Also, I love that now when I put on a dress, I’m making a fucking STATEMENT.

This is so relevant to my life. I spent years wanting short hair and hesitating because I didn’t ‘have the face for short hair’. And then one day I just got angry, because like nobody says to a guy “Your hair looks terrible on you, you should grow it out, you really can’t pull off short hair”.

I just remember the way my heart was beating really fast as my hair hair fell to the floor around me. It was the best feeling ever. I finally felt like I was me. Plus now I actually take care of and style my hair on a consistent basis.

Kate/Kade/Kadte – as usual, a beautifully written piece.

I’m still kicking myself for not meeting you at a-camp. I meant to, but then got drunk and forgot.

I have a feeling the elements of my story occur often at a-camp.

Getting my hair cut was like snipping the last string between me and “normal” society. After that, there was no going back, and I have never looked back.

I cut my own hair when I was 7, shut myself in the bathroom and got increasingly worried as I could not get it all matched up and just kept cutting and cutting until my sister opened the door, saw me, and screamed “Moooooooom!!!!!!” I was taken to the neighborhood woman who cut hair around the block to have it all trimmed up and the first thing I said when she was done was “I look like a boy.” I felt pretty worried.

The only other girl my age in the neighborhood was April. She had long brown hair to her butt and a basement stocked completely full of the coolest toys and so many barbies. Her mom chain-smoked, which really impressed me. I was intimidated and enchanted with April. Monday morning at the bus stop she took one look at me and told me she was no longer my friend and wouldn’t talk to me. And as far as I can recall, she never did again.

Then I moved, and with the name Robin other kids thought I was a boy at first, which made me feel vaguely ill at ease (that was the least of it, really, I got teased pretty badly with that move.)

My hair has been shortish throughout most of my 20s, but never super-short, and the past few years I’ve been growing it out, in part to be able to be flexibly professional looking since I have a neck tattoo. But the urge to go really short has gotten itself under my skin. My hair is longer than it has been since before puberty, and I love it, I feel distinctive with it. I’m finally in a job I think I can stick with for a few years and that I think it’d be fine to go for short hair with a visible neck tattoo, esp after I’m more established. I’m going to keep growing it for about a year and then bam! get the short hair cut! I’m excited to see how long it will get and excited to experience the transformation from long to suddenly short, both for how it feels for me and for how it changes how others act towards me. Some day in my life I want to experience what it’s like to go totally shaven too, but that’s a big leap and requires perhaps certain life circumstances to get away with it.

So, that was long-winded. There is definitely a lot to think about about hair. Thanks for this piece, Kate.

I seem to be the only person on the complete opposite side in this comment sections. Having short hair as a kid constantly led to adults misgendering me, so now I’ve sworn never to have my hair that short again because it just seems to be too much anxiety for no pay-off.

The irony is that my mom constantly nags me to cut my hair because she liked it short. Yeah, thanks, but no, her affection for my short hair led to a very long and subtle identity crisis, so that’s not reason enough.

Ah, this is so so great.

My first attempt at a queer cut, I showed the stylist a photo from one of the AS galleries, and she kind of freaked out (presumably) for me (who I assume she maybe read as straight) and was like: ARE YOU SURE YOU WANT IT THAT SHORT. ARE YOU SURE. And I had to reassure her like 8 times it was truly going to be fine. It was one of those awkward situations where at the heart of it, she seemed to be scared to make me look like a queermo and that I would be mad that she made me look like a queermo, when, hello, that’s why I was there. I then realized it probably wasn’t safe for me to out myself/slash I did not feel comfortable enough to out myself. Flashforward a few months when my hair had grown out again. At that point, I was in SF and I went to this AWESOME Asian dude stylist. I showed the same picture from the AS gallery AND a picture of my last hair cut to give him reference, and he was all: She clearly didn’t do this photo justice because that looks nothing like what you wanted. And then he whipped my hair into queerness. Thank you, Asian Man Hair Stylist, for reading the photo correctly.

Kate, your hair is awesome and I am super jealous of how awesome it is.

That initial reaction the girl who cuts my hair had made me concerned too. I thought ‘Oh, crap. She figured me out. Here comes the Uncomfortable Situation.’

I couldn’t have been more wrong. Perfect example of ‘Don’t judge a book by its cover,’ which is so rare in a small town. Every time I walk in, which is often because of how short it is, her son and I have a long conversation about Ninja Turtles while I wait and she often says how much she likes the cut and doing something different.

Thank you world, for small things like this. Also, I just realized I know an embarrassing amount about Ninja Turtles for an adult.

Once I had a gift certificate to this salon and so I went and the stylists were talking about how this girl’s sister was going to an all women’s college and the girl cutting my hair was all like “tell her to be careful there are a lot of those …weird girls, ~~if you know what I mean~~” and they exchanged knowing homophobic glances. It was super uncomfortable. I still haven’t found a hairdresser I’m totally comfortable with.

Great article!

There’s nothing better than a haircut, and I’ve had about every style I’ve ever admired, and every color too! I’m 33 and in a rather creative career, so I can get away with a lot more than many of my peers. My mom usually loathes it (which I’ve come to translate into “my hair must look awesome!”), and partners must grow accustomed to my constant hair change because I’m certainly not asking permission before zipping to the salon. I rest femme of center, so each new hair color means I get to change up the makeup colors and clothing that look good with it. I consider growing it out now and then, but I’m so addicted to the ease and style of short hair (especially in the hot hot South) that it never gets past my jawline. Many people comment, saying “I wish I could pull off short hair” or “I wish I was brave enough for a pixie cut/undercut/asymmetrical cut/etc” and I’m like “there REALLY is a short cut out there for everyone, and come on, hair grows back so have some fun with it!”

Your hair in your transition pic is exactly what I want. I’d like to print it out for the hair stylist.

“THIS. And shaved on one side.”

Beautifully written, Kate! And your hair looks AMAZING in that last photo. Your face has the expression of someone who has chosen to be unapologetically, authentically true to themselves.

I just went through all the steps to register here, edit my profile, activate my account, etc., just so that I can say:

Get out of my head.

Seriously. I can’t wait to read your articles each week, not only because they are so well written but because you tap into SO many unspoken discourses that I’ve never been able to (or sometimes never even thought to) express. The similarity of so many of our experiences is uncanny.

I’m glad I couldn’t keep myself from saying that anymore, because now I have an account, which means I can comment more often.

Thank you. Just…thank you.

My current haircut (which is about 3 weeks old now) is kind of like your first short-still-feminine cut. I got an undercut last summer and have been fantasizing about a short haircut, well, for years, but especially since last summer. I’m fairly certain I am more femme than butch, but it was important for me to make myself read more queer. A way to combat my femme invisibility, perhaps.

But also, I think it’s also got to do with coming out. I am out to my friends and coworkers, but I’m still having trouble coming out to my family. I suspect they suspect, but the facts have ne’er been spoken aloud.

I feel you 100% re: coming out so often being based on the others versus the individual. Maybe styling my hair shorter (read: more queer) is helping ease my family into the idea of their little girl, their sister, their aunt, etc. and her love of women.

Much like you, I have been told throughout my life that my hair was my best feature. Everyone always commented on how soft and pretty it was.

But I always kinda hated it.

I remember watching something on tv when I was about 14, thinking to myself that I wanted this haircut, the one where the sides and back were shaved leaving the hair long on top.

I had that haircut stashed in the back of my mind with every trip to the salon to make myself ‘look more like a girl.’

Perms, and colours, and straighteners.

Layers and fringe.

Every style getting farther and farther away from my goal.

Then I graduated high school, left my conservative suburban town, and went to art school.

I looked around me and promptly noticed how much no one at art school cared about how your hair was cut, and realised how amazing this opportunity was to discover myself.

So I tested the waters and got myself a crazy asymmetrical art student haircut.

Not being out to my family as anything other than very girly and very straight, this caused some waves. So I made sure I still wore lots of shiny jewelry and dresses to appease them all.

This sort of pattern of weird haircuts and dresses continued for three, very long, years.

Until the beginning of this summer.

I’ve been slowly but surely coming to terms with my sexuality and how I wish to present, so the steps have been tiny and virtually unnoticeable. Until you compare old and new pictures and you realise my outfits have a decidedly more masculine tone nowadays.

But the most self affirming thing I still had left on my list (right underneath ‘own a button down, a bow tie, and a strong sports bra’) was to finally get the haircut of my dreams.

And I did.

I have to say, even though I’m still spelunking in the dark recesses of the closet around my family, I finally feel like I’m presenting me.

Who knew a haircut could make you feel so freaking good, even when everything else still kinda sucks.

Very late to the party, I know.. but you look fantastic with short hair!! I get to mine with the clippers on a regular basis too… grew it long a few times, but always back to the clippers in the end *g* Thing is, I hate the feel of product on my hair, but it really needs something to style it with- but I just can’t stand it feeling all sticky…:-/ what to do, eh?