The sun seemed to shine a little brighter the Tuesday morning that Brown University student, Lena Sclove, stood in front of a group of 50 or more students, staff, and Providence residents to talk about the traumatic event that has affected her life for the last eight months. Standing in front of the University’s Van Wickle Gates, Sclove addressed the crowd of supporters. “It’s sort of bittersweet,” Sclove began with a small smile on her face. “I haven’t seen a lot of you and this campus has come to mean a lot of things to me. And it’s become a very scary place for me, and that’s what I’m here to talk about.”

On August 2nd, 2013, a fellow Brown University student strangled and raped Lena Sclove. The two students, who were at one point good friends, had previously hooked up but had decided to end the relationship prior to the incident in question. However, on August 2nd, after a party, the male student assaulted Sclove even though she reports saying “no” at least seven times. Within two weeks of the attack, Sclove reported the rape to the Brown Office of Student Life under the assumption that the process would bring her some sense of justice. On the contrary, Sclove was subject to a long and difficult series of meetings with the university’s board of conduct, a judicial process that took three entire months — all while the rapist attended classes and lived on the same campus as Sclove. She remembers being forced to see her attacker in the university’s campus center, in libraries and in dining halls while attempting to find some sense of comfort and justice from the school’s administration.

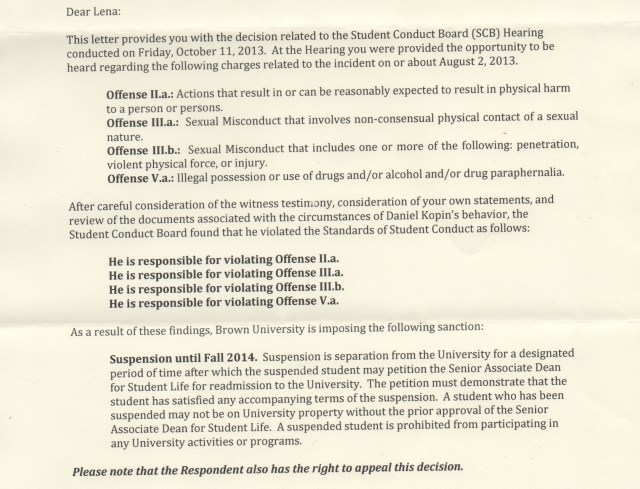

Sclove’s official hearing took place on October 11th, 2013, before a student conduct board panel composed of a student, a dean and a professor over two months after the rape. A week after the October 11th hearing, the board notified Sclove that they found her rapist guilty of the following four charges: (1) actions that result in or can be reasonably expected to result in physical harm to a person or persons; (2) sexual misconduct that involves nonconsensual physical contact of a sexual nature; (3) sexual misconduct that includes one or more of the following: penetration, violent physical force, or injury; (4) illegal possession or use of drugs and/or alcohol and/or drug paraphernalia. Interestingly, the board sentenced Sclove’s attacker to a suspension of two years but Brown’s Senior Associate Dean of Student Life, J. Allen Ward, reduced the sentence to a one-year suspension. In spite of this ruling, Sclove was told that the rapist would return to campus in the fall of 2014, even though he had been allowed to remain on campus for the entirety of the trial and his “year suspension” in reality would only amount to one semester and a few weeks away from the University.

Sclove immediately appealed the decision (the rapist did not) because the suspension would mean that the attacker returned to school while Sclove still had two more years to complete as a student, and that she would not feel safe attending classes knowing that the man who raped her was still allowed on campus. Vice President Margaret Klawunn, who receives student appeals, denied Sclove’s request. The Brown administration defended its decisions and actions based on “precedent” of past sanctions.

Along with the University’s lack of empathy, Sclove suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and migraines towards the end of the Fall 2013 semester that lasted for two weeks. Furthermore, just before Christmas, she woke up with a lump on her spine — a manifestation of a cervical injury sustained from the rapist strangling her — and Sclove was unable to walk for two months. Because of the spinal injury, Sclove had to go on medical leave, and lost the one semester of peace she would have had on campus before the rapist returned. Now Sclove is two semesters behind in her academic career because the arduous process of the board hearings limited her to a half-course load and because Sclove’s medical injuries prevent her from returning to school at all until the fall. Sclove asserted that even with her family to support her financially and emotionally through the hearings, the entire procedure was incredibly difficult and that Brown’s system of dealing with assault privileges students who have the time and energy to pause their academics and jobs in order to receive even a little justice for their suffering. Many students don’t have the option to demand that the university punish their sexual assailants or rapists.

Sclove’s sexual assault is far from the first or only instance of sexual misconduct, harassment, or rape at Brown University. In 1990, the University captured national attention when media sources found out that students listed the names of men who allegedly sexually assaulted them on bathroom stalls. Up to 30 men’s names were listed in the stalls of the Rockefeller Library women’s bathrooms, and the New York Times reported that even when janitors cleaned the names off of the walls, students re-wrote the lists on other bathrooms across the campus. Six years later, Adam Lack (who was class of 1997 but graduated years later) was accused of raping a fellow student who claimed she was too drunk to remember what happened the night of the incident and could not have consented. In 2010, Will McCormick III made a private settlement where he agreed to leave Brown University as long as the woman that accused him of rape did not file charges. While the last two cases are some of the most famous Brown University sexual assaults — mostly because the accused rapists sued the school, claiming that the allegations were false — there are undoubtedly many more cases reported and unreported.

Sclove’s courageous push to bring her attack to the spotlight in order to call attention to the way her university mishandles sexual assault cases is indicative of a greater crisis. Universities and colleges across the United States have a long history of brushing sexual violence under the rug or punishing rapists with a slap on the wrist. Students have always voiced their concerns about this trend in some way or another, but recently, university and college students have coalesced to hold their institutions accountable. Earlier this month, a group of 23 students working under the name “Our Stories CU” decided to file Title IX, Title II, and Clery complaints against Columbia University for the institution’s inadequate response to and treatment of sexual assault on the Ivy League campus. At Harvard, on April 3rd, two students confirmed that they had filed a complaint with the U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights against the University, on the grounds that the institution’s sexual assault policies violate Title IX. (Title IX is a law passed in 1972 that establishes gender equity for every federally funded educational program.)

In the government, prominent politicians like senators Claire McCaskill and Kirsten Gillibrand have dedicated efforts to challenging the military and universities to dealing with sexual assault with more care towards survivors and with less leniency towards the perpetrators of sexual violence. Sen. McCaskill clarified how sexual assault manifests similarly in the military and in universities:

“Reporting a sexual assault is immensely difficult no matter where it occurs, because it is the most personally painful and private moment of a victim’s life, but it is often exacerbated in these closed environments — where it may be difficult to come forward and report, because victims often feel they are under a microscope, may often know their attacker, and may have difficulty navigating the complexities on how to report these crimes.”

It is true that in the case of universities and colleges, the administrations must negotiate the fact that both the attacker and the survivor are probably affiliated with the institution and that the institution is then liable for both sides of the situation. However, these institutions often choose to defend the perpetrator of the crime instead of the person attacked. We live in a society that thrives because of systemic misogyny and endorses rape culture legally (as seen through Brown University’s careless treatment of horrific cases of sexual violence), socially (experienced any time someone responds to a rape accusation by suggesting that the survivor “was asking for it”), and in the media (every time a TV show or movie glorifies a man having his way with a partner with absolutely no consent).

At the end of Lena Sclove’s press conference, she reminded any survivors of sexual assault listening to her that they did not do anything wrong. Sexual assault survivors never deserve to be attacked, violated and humiliated by another human being. Universities that choose to protect rapists and sexual assaulters because it’s too “hard” to publicly condemn the spiritual, emotional, and phyical trauma that is rape institutionalize the misogyny and sexual violence endemic in our society and continually wrong their students.

To sign a petition to seek Justice for Lena Sclove and sexual assault survivors everywhere, click here.