This part essay, part research project started out as a joke. I wanted to know if one of the unexpected benefits of Black people always dying first in horror movies was that we could never be zombies. I’ve kept an ofrenda by my bedside since I was old enough to know better, but still — I wasn’t thinking about santería or vodun. Not yet, anyway. I hadn’t yet considered bodies swept under by salt of oceans or the sharp tobacco of my Granny’s Newports that still haunts my nostrils when I’m not looking for it.

I hadn’t thought about the ways our dead are often, also, undead — kept alive in the ways Black people seem to routinely and uniquely invoke our ancestors on t-shirts and in memes. Dr. Martin Luther King photoshopped smiling proud with gold teeth and a durag shared every year like clockwork in my group chat on February 1. Aretha Franklin and Rosa Parks offering Michelle Obama a ride in a pink Cadillac on cotton-poly blend t-shirts stretched across metal racks from vendors at festivals in the too hot summers. Our funerals are homegoings. We don’t say goodbye.

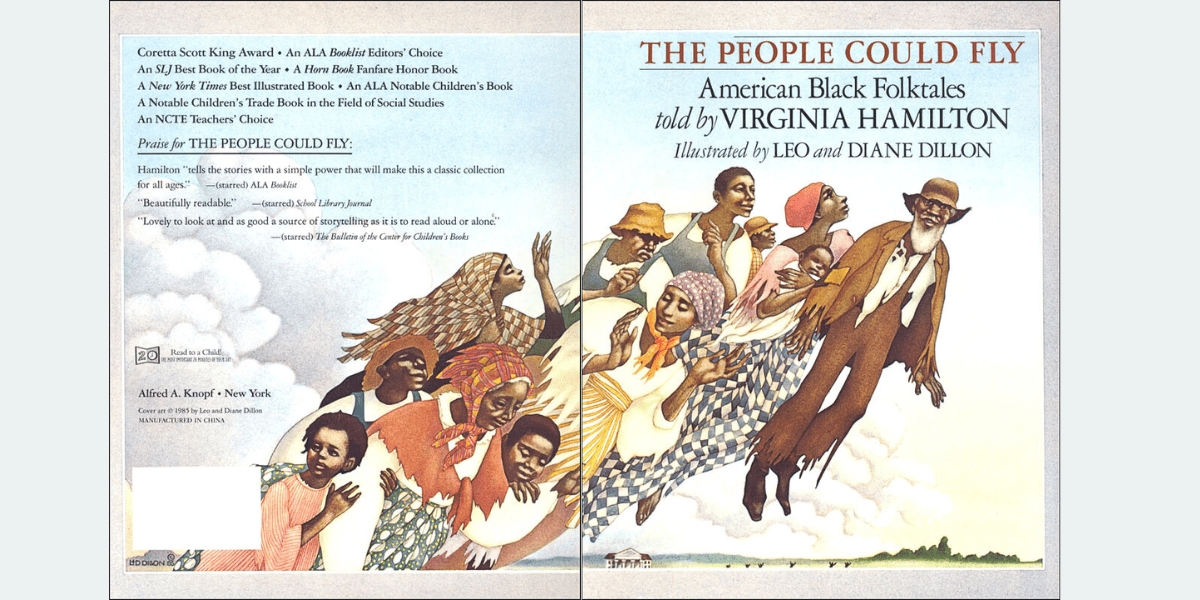

There was a trend in 1980s children’s literature, especially if you came from book-ish and Afrocentric families like mine. Black children’s books were turning our folklore and oral traditions into “traditional” picture books. John Steptoe’s Mufaro’s Beautiful Daughters, where two sisters are taught the importance of kindness and inner beauty over looks and poor temperament, was an instant classic. I was always partial to Patricia McKissack’s Mirandy and Brother Wind, where a little girl tries to capture the wind itself to be her partner for her town’s dance. But it’s Virginia Hamilton’s The People Could Fly that I’ll never forget. Its cover, illustrated with aching care by Leo and Diane Dillon, shows us in worn clothes, sunhats, and headscarves soaring above and away from the plantations that tried with every ounce of cruelty and inhumanity possible to break us, but instead there we were — in the clouds against a golden sky.

I didn’t understand The People Could Fly as a child. Instead of a picture book, it’s a collection of 24 stories, the final of which tells the tale of a magical African people who lose their wings when they are forced into boats to America, ultimately becoming slaves. One day, one of these people, Sarah, is beaten while holding her baby on her back. When nearly all hope is lost, an old man named Toby conjures back Sarah’s flying powers. She and her baby both fly away. The next day, more enslaved people pass out due to heat on the fields, and once again Toby appears. He whispers into their ears, and each one of them flies away. By the time the owners realize what has happened, Toby says his incantation one remaining time and flies away himself. Virginia Hamilton, the first children’s book author to ever receive a MacArthur genius grant, liked to say that her writing existed “as a triad of the known, the remembered and the imagined.”

I’m sure not everyone would buy their four-year-old a book about slavery, but the first time I was told my people were once enslaved, I was also told we were free.

And so, to a people who do not die, who are once and always once again free — what can it possibly mean to be a zombie?

I’m supposed to be talking about movies right now.

In movies and on TV, zombies aren’t ethereal, liberating each other and floating together far away from their pain. They aren’t filled with love, like a grandma’s cigarettes that haven’t left your senses in nearly 30 years. They aren’t the tucked away smile of a well-timed joke that’s cloaked in such a Black-specific pop culture humor that no else will understand.

Zombies have sunken lifeless eyes and missing limbs. Their decaying skin peels away from itself, leaving exposed undersides of bloody, droopy flesh. They stumble forward at random with no control, looking for what’s left of the living among them to feast off of. They exist only to maim and create mayhem. Zombies eat brains, they pull arms and legs from torsos. They aren’t granted peace, even in their (un)death, and they infect others to that same unspeakable fate with a single solitary bite.

At this point, it’s well known that, as Zachary Crockett and Javier Zarracina wrote for Vox in 2013, “the undead have been used by filmmakers and writers as a metaphor for much deeper fears,” including fears of “racial sublimation.” Purposefully lifeless, zombie forms are a blank canvas, molded to mirror perceptions of anxiety, threat, and unease.

It’s ironic, then, that our understanding of zombies first comes from enslaved Africans’ own fears about the loss of their bodily autonomy. In her thesis “Zombified and Traumatized: Healing in Black Women’s Zombie Literature,” Mikayla Johnson submits that:

“The origin of the zombi astral has been traced to West Central Africa. Residing along the Congo River are the Bantu and Bakongo tribes. The tribes believe in a deity known as Nzambi who presides over the people in the Zombo region. The Congolese residents possess a process of creating ‘bottle fetishes’ known as zumbi. This practice entails a form of soul enslavement. A sorcerer or ‘dark priest’ entraps a person’s soul in a bottle thus leaving a shell of the person the enslaved was before… While these human husks are far from the flesh consuming zombie we see in popular culture today, they introduce the foundation of entrapped servitude that parallels the physical bodied zombie.”

During the Transatlantic Slave Trade, as Black people faced even greater fears of enslavement, zombie narratives continued. In Haitian Vodou, a belief grew that those who died from an unnatural cause would have their souls linger. During that haze in between, a bòkò (a person with the ability to manipulate the dead) could step in to keep these bodies doing endless work, with no agency of their own and suspended in a state between life and death, a zombi.

For The Atlantic, Mike Mariani researched a similar, but still its own distinct, historical shade on the origin story of Haitian zombies and Vodou:

“The original brains-eating fiend was a slave not to the flesh of others but to his own. The zombie archetype, as it appeared in Haiti and mirrored the inhumanity that existed there from 1625 to around 1800, was a projection of the African slaves’ relentless misery and subjugation. Haitian slaves believed that dying would release them back to lan guinée, literally Guinea, or Africa in general, a kind of afterlife where they could be free. Though suicide was common among slaves, those who took their own lives wouldn’t be allowed to return to lan guinée. Instead, they’d be condemned to skulk the Hispaniola plantations for eternity, undead slaves at once denied their own bodies and yet trapped inside them — soulless zombies.”

Here, zombies become a looming threat, a warning against taking one’s own life, even under extreme and unimaginable duress, not entirely unlike other Catholic belief systems that name suicide as a sin. Marrying Afro-Indigenous spirituality, such as Vodou, to similar tentpoles of (in this case, French) Catholic faith was often commonplace in the Caribbean as a means of survival.

When the United States occupied Haiti in 1915, journalist and occultist William Seabrook was researching Vodou when he claimed to have seen zombies for himself at the Haitian American Sugar Company, where: “The supposed zombies continued dumbly at work. They were plodding like brutes, like automatons. The eyes were the worst… They were in truth like the eyes of a dead man, not blind but staring, unfocused, unseeing.” Vox correctly notes that Seabrook’s racist assumptions about seeing the undead was actually “most certainly slaves employed by American manufacturers, made to work 18-hour shifts and living in squalid conditions” that often came with American projects of imperialism.

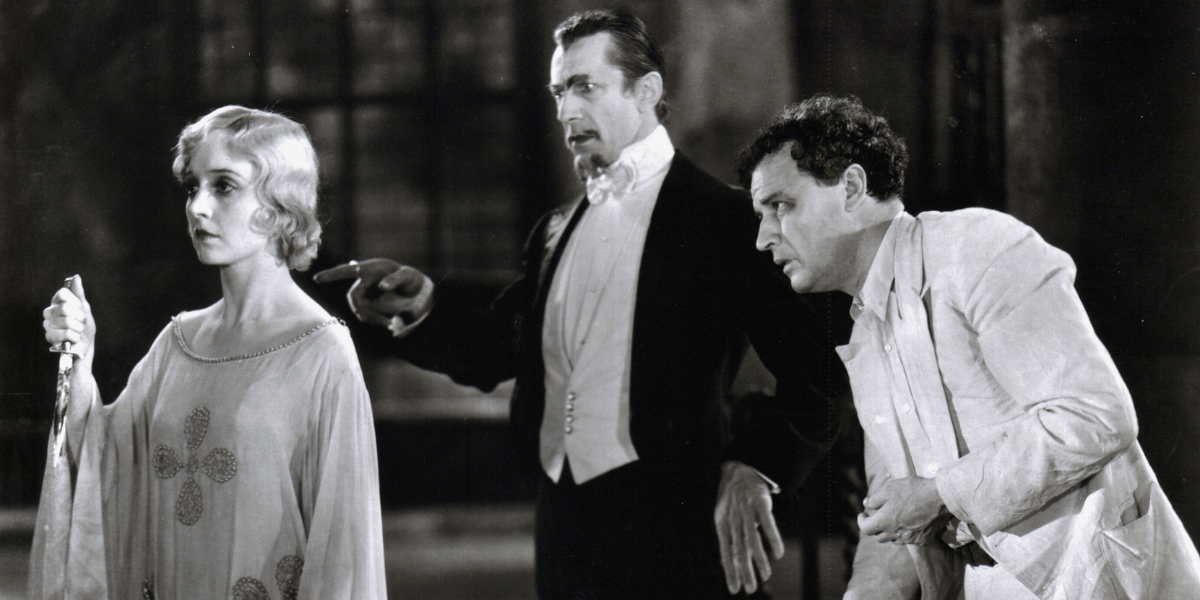

Even still, Seabrook’s words served as the foundation for 1932’s White Zombie, the first feature-length zombie film. Released just one year after Dracula and Frankenstein, White Zombie manipulated America’s fears of Black spirituality and turned it into a core horror archetype.

Refracted through a white gaze over the last 91 years, today it is rare to see Black zombies. There are multiple Reddit threads dedicated to this phenomenon in video games. In 2013, when The Walking Dead was one of the most watched shows on television, Jenn Fang asked, “Where Are All the Zombies of Colour?” She noted that while the series was set in Atlanta — a city at the time that was “52% Black, 10% Latino and 5% Asian” — the clockable and overwhelming majority of the zombies were white. In 2015, Grist noticed a similar pattern emerging during the premiere of The Walking Dead’s spin-off, Fear the Walking Dead, which prioritized “the high value of white life in a fictional story about a real city where white people are a numerical minority.”

The brain-munching zombies of white imaginations cannot hold the complexities of how Black people understand death and life-after-death, because the genre was created by twisting extremely valid Black fears about loss of autonomy and overwork into something monstrous. They’ve never been forced to wonder if their people could fly. But it would be a mistake to assume that escapist fantasies designed for jump scares and junk food are not still personifying social and political anxieties around race.

In fact, as Matt Thompson observed for NPR:

“The thing about good zombie fiction… is that the zombies are never the most horrific thing. Zombies don’t typically have the capacity for complex thought — they don’t execute stratagems, play politics, torture people. All they do is feed. The true horror in any zombie story worth its salt is what other people do when faced with the zombie threat. Zombies are merely relentless; humans can be sadistic.”

(Italicized emphasis my own.)

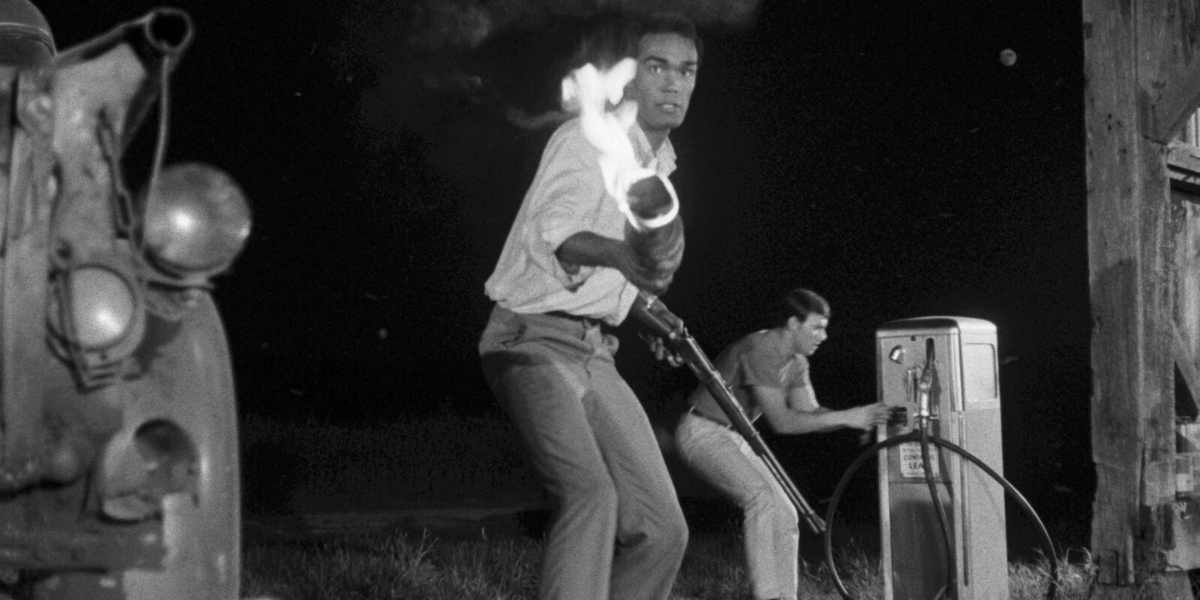

1968’s Night of the Living Dead, George Romero’s seminal work that redefined zombie horror for filmmakers and audiences alike, takes place with Ben — the film’s Black protagonist, played by Duane Jones — rescuing a young white woman named Barbara from a mass of zombies. Ben finds himself trapped with a group of white people, all of them trying to survive the night, ultimately only for Ben to make it out as the lone survivor. Ben escapes, just to be shot by a white sheriff’s deputy at the end.

As an epilogue, the film’s closing credits feature a series of still images. In them, Ben’s body is in various states of torture by a mob of (assumed to be) white Southerners. In the final shot, there’s a fire not unlike rings of fire that have become closely associated with the KKK. Overlayed with the image, sounds of dogs barking can be heard in the distance. Romero has previously stated that they finished editing Night of the Living Dead the same night he heard the breaking news of Martin Luther King’s assassination. Zombies are the draw, but it’s not a stretch to understand who the real ghouls are.

“Some memories are omens,” reflects Ada, the young Senegalese protagonist in Mati Diop’s 2019 quiet thriller Atlantics. The poetic, sensual supernatural romance turned haunting revenge heist film pulls from Haitian zombi mythology as Ana’s lover, Souleiman, along with the spirits of other Senegalese day laborers who lost their lives while crossing the Atlantic Ocean to look for work in Europe, after being left without their rightful pay in Senegal, possess those they left behind to do their bidding. The possessed mob demands their owed pay from the business tycoon who built his new sprawling high-rise on their labor, and once their pay is received, they possess him as well, forcing him to dig their graves so their spirits may find the rest that has been robbed of them in the ocean.

With Atlantics, Diop became the first Black woman director with a film featured at Cannes. It’s a glimmer of restoration. An opportunity to break away from William Seabrook or White Zombie, from the countless white horror fantasies gleaned out of misconstructions of Haitian and Black diasporic spirituality.

If memories are omens, then exploring Black life-after-death opens up avenues that push beyond trauma. Pathways once closed off — boxed into linear beginnings, middles, and (often violent, unjust, cruel) ends — can now instead be reclaimed as limitless. Zombies don’t have to haunt. And not all hauntings are bad.

In their 2019 Lambda Literary Award-winning novel The Deep, Rivers Solomon creates the wajinru, a water-breathing society of merfolk who are the descendants of thousands of pregnant African women thrown overboard from slave ships crossing the Atlantic.

The women drowned, but their babies survived, evolving into their current form. And through them Solomon asks, “What does it mean to be born of the dead? What does it mean to begin?”

Comments

Thank you for this piece, Carmen!

It is one of the best essays I have read here. Thank you so, so much.

amazing mahalo, i’ve shared this with my loved ones and am xcited to check out Atlantics and The Deep!

Fascinating piece. I did know about the Haitian Vodou zombi but had no idea it went so far back to the Congo.

Thank you for your work.

Thank you so much for this piece – Atlantics is a gorgeous film. It makes me think of critiques of the Handmaid’s Tale – for white women, the greatest horrors are what generations of women of colour have been subjected to to build capitalism.

I don’t really watch horror (my tolerance for scary or violent films is barely more than Disney), but I loved this essay!