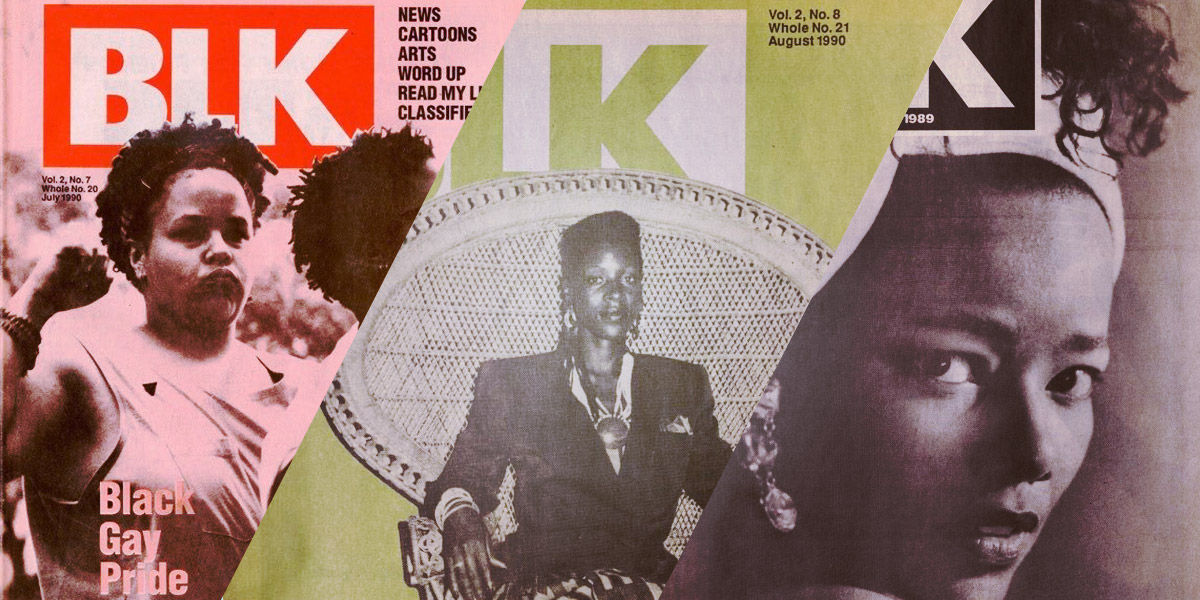

“Where the news is colored in on purpose.” That was motto of BLK Magazine.

In 1988, the first issue of BLK was published in Los Angeles by Alan Bell. Bell, who got into the world of queer indie media by overseeing the publication of Gaysweek in New York between 1977 and 1979, designed it to be a safe haven for black gays and lesbians that would rival the titans of black publishing – JET, Ebony, or Essence. In 2014 Bell told Dr. Kai M. Green, whose dissertation “Into the Darkness: A Black Queer (Re)Membering of Los Angeles in a Time of Crisis” remains one of the few lengthy studies of the magazine, that he wanted to create “a Black magazine for gay people and not a gay magazine about Black people.” The distinction is important.

There’s been a lot of talk online lately about the so-called death of queer media. I say “so-called” not because isn’t a brutal time to be working for independent media, and especially for media that caters to LGBTQ+ communities that have not often been valued by the mainstream, but because calling for our death implies that this is the end. There has been gay media for as long as there have been communities of gay people. Our stories have to be told, and there will be those who’ll be there to record them. That’s not going to change. The premature call of our demise flattens that important history; we’ve reached back and carried each other before, we will do it again.

In his pocket of queer black Los Angeles in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, for communities that were facing all but a genocide in the wake of HIV/AIDS, Alan Bell took up that mantle. When BLK first published, it was a 16 page black-and-white newsletter with a circulation of roughly 5,000. By the time the end of its publication, it had grown into a 40 page magazine with full color covers, a paid subscriber base, national product advertisement, and global distribution reaching 37,000 people. It told our stories.

And that history is foundational. It gets into our core and changes how we see ourselves. In 2020, when we talk about the Stonewall Uprising – widely considered to be the start of the modern gay rights movement – it’s become more common (though still, not nearly enough) to uplift the names of the black and brown trans women like Marsha P Johnson and Sylvia Rivera who were at the frontlines of that fight. In fact, the duo finally have a statue in their honor in front of the club. But in June 1989, a date squarely at the center of Stonewall’s active white-washing of history, BLK honored it’s 20th Anniversary with this letter from the editor by Mark Haile:

In the retelling of the tale, history has become myth and desperation is remembered as romance. Changes and omissions, whether accidental or intentional, are nothing new in American History when it concerns people of color, gays or women.

And the Stonewall Legend does concern people of color. If that sultry weekend’s street theater is to be regarded as the launching pad of the modern gay rights movement, then it is essential for us to know the key players who started it all: drag queens, hustlers, jailbait juveniles, and gay men and lesbians of color. The out casts of gay life thus showed homosexual America how to make a fist, fight back, and win self-respect.

It would take yet another 20 years before the majority of LGBT media would catch back up. I realize of course that you are reading this from the pages of a queer independent media company, so I probably don’t have to convince you, but this is why having independent media is so vital. If we aren’t telling our stories, and telling them the right way, lifting up those who are “the out casts of gay life” and pointing out who does the work that the rest of us get to reap the benefit of, then who will?

In addition to having black lesbians on the editorial staff of the mothership magazine; BLK also created a spin-off, Black Lace, an erotic magazine for women. (There was also Blackfire, an erotic magazine for men; Kuumba a co-sexual poetry journal; and Black Dates, a calendar of events across queer Southern California). Black Lace sadly only was in print for four issues – though that’s not much worse off than Kuumba’s five issue run – and I am once again indebted to Dr. Green, who was able to go through the issues as a part of his work.

In the inaugural issue of Black Lace, editor Alycee J. Lane opened with a letter that grapples with what it means to talk about black women’s queer sexuality publicly:

FINALLY! BLACK LACE AFTER TOO many late night and early morning conversations and political debates and asking should I? Or shouldn’t I? And worrying about the devastating infinite measurements of political ‘correctness’ and meditating on what it means, feels like to be an African American lesbian loving other African American lesbians, sex and multiple orgasms, knowing—do you hear me? –knowing that we have been and continue to be sexual animals to the Amerikan imagination, working our asses off to prove the perversion of that imagination all the while internalizing the frigid Victorian sensibility of no sex, I don’t think about sex, I don’t want sex, I don’t even know what my own pussy looks like.

It’s the last line that I’ve come back to most. “I don’t even know what my own pussy looks like.” It somehow both breaks my heart to think of a woman who’s risking so much to be herself and love and fuck openly with whomever she pleases, and still not knowing what her own body looks like intimately; and also makes me so unspeakably grateful for the Alycee Lanes past who wrote like this so I could sit here as an editor of a publication that writes openly about dildos and strap-ons and orgasms three to four times a week. So much of what we take for granted as queer women, even as black queer women who don’t always have much, that we can reach with our fingertips – others had to claw at with their open palms and pray to hold on. (Fun fact! Black Lace’s second issue actually took on my favorite subject – Dildos!)

I first discovered the covers for BLK in a Twitter thread about a month ago and the images stayed with me. It’s so easy for our history to get lost, to slip away. When I originally mapped out this Black History Month post, I thought it was going to end triumphant. I wanted to tell you how ecstatic I was to “discover” this black queer history. And I am! But I’m also somehow… wistful? Perhaps melancholy?

BLK stood on its own for six years and 41 issues. Black Lace lasted half of a year on four issues. Autostraddle has been here for a decade, which in gay years might as well be a millennia. I’m really proud to stand on the shoulders of Alan Bell and Alycee Lane; I feel connected and kinship with them – imagining that they had a lot of the same gay and dyke drama, and money drama (always, always money drama) that I have with my writers now. I think of the small office in Los Angeles that was BLK’s home and wonder what it would look like alive today. Would it feel the same frenzied, hilarious energy that I share with Autostraddle’s black writers whenever Young M.A releases another video of her licking her lips?

What I said earlier in this piece is absolutely true. I know that queer media isn’t dying, because storytellers don’t die. Just this morning, I was able to commission a black trans woman to write about Zaya Wade’s coming out. I know that it’s my job to hold the line for as long as I can, and then make way for the next person to do the same. But I guess today I am a little bit sad anyway. I want a thousand more issues of Black Lace. Sometimes its very tiring to figure out the road there.