Melanie was born on August 5, 1982. I know this because I fell in love with her in fifth grade. I knew the way I giggled around certain boys and wanted them to notice me were “crushes,” but I did not know how to name what I felt for Melanie. I decided she was my best friend, so I wrote her a note, tucking it carefully into the arm of her winter coat to be found when she put it on for recess, asking if she felt the same. I still have her reply, written in the looping script of a ten year old:

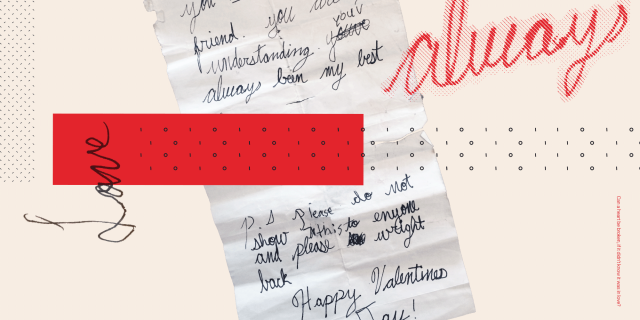

Dear Micha,

You are my best friend. You’v always been my best.

Love, Melanie

Ps. Please do not show this to enyone and please wright back

Then, in extra curly cursive at the bottom: Happy Valentines Day!

I kept Melanie’s note tightly folded and hidden. When I was brave, I would close my bedroom door to dig it out and reread it, bringing me a thrill I never understood. Within a year, Melanie would transform into a bully with the emotional brutality that only pre-teen girls can truly master, resulting in tears so copious that our school established weekly group counseling sessions for the girls in our class. I turned cruel to win her favor, but was coldly cut out of her world anyways. Can a heart be broken if it didn’t know it was in love? I wouldn’t know – in the sense of naming myself to myself – how I felt about Melanie until I felt the same thing again, three years later, for Ilana.

Ilana and I had the same birthday, July 3, a star-crossed fate that thrilled me with its potential for intimacy. The summer after eighth grade, she hosted a small joint 14th birthday party for us with a handful of friends. We gathered in her basement, then went out to the park around the block to open gifts and hang around without parental interference. I was so in love that I imagined it an honor to share the day with Ilana, and followed her lead towards the maturity of an informal gathering rather than a full-blown birthday party. It was underwhelming, but I felt special, sophisticated.

I knew, by this time, what I felt for Ilana. I was also infatuated with our friend Mark, with whom Ilana had an on-again off-again relationship, in that vague middle school way. But it took another girl in our class confessing her crush on Ilana to me to reveal my own feelings to myself. When Sara told me she liked liked Ilana, I was angry. Infuriated. I could not make sense of my own reactions, as it wasn’t prejudice – I counted many gay and lesbian folks in my family and community – so I stewed on my own anger for days until it dawned on me that the feeling might better be named jealousy. I was jealous of Sara, less so for her potential to date Ilana than for her ability to openly declare her attraction. Such confidence in her own desires only sent mine further into hiding, even as I recognized the fullness of their scope for the first time.

I learned, at some point later, that Ilana’s birthday was actually on January 3 – my half birthday – and that she had lied about this and many other things, mostly inconsequential. We saw less of each other after that summer as we started different high schools, and by the time my father’s 46th birthday, on November 5, rolled around, we were shifting apart. When he suddenly died a few weeks later, on the 22nd, November became doubly marked – the shadow of his birth always coming like a foreshock to the later quake of grief.

![]()

I learned how to mourn a parent from my mother, who lost her own mother to Hodgkin’s Lymphoma on April 1 when she was eight years old. Although her mother’s death wasn’t a surprise – she had only ever known her mother as sick – my mom refused to believe her father when he reported the news. It was April Fool’s Day, after all, and he was a sadistic abuser who was cruel enough to joke about such things. My mother lit a 24-hour Yarzheit candle every sundown on the last night of March, and we never played pranks for April Fool’s.

I was already an inward-facing person. I had never joined in when my friends swapped confessions of crushes and pressed for mine, as I didn’t imagine it possible that anybody, boy or girl, might like me back. My father’s death sent me deeper into hiding. I moved through my high school years with the sense that the world was wildly alive, too bright and too real, but that I might always be alone in it. I poured myself into school work, earning the highest grades in my class each year. I lost touch with all but my closest friends from before, and kept my new classmates at a friendly distance. When I graduated, a year early, I had still never kissed anyone, had never even admitted that I might want to. I chose a college far away, somehow knowing that when I got there, everything would change.

![]()

Des was my first girlfriend. The word was always an awkward fit, and we made up many of our own, but at the same time I loved having a girlfriend, the way it made something I felt about myself seem real and recognizable. We got together near the end of our freshman year, a few months after my first boyfriend and I broke up. When Des and I told our rugby teammates that we had started dating, some people replied with surprise – not that we were together, but that we hadn’t already been for months. We were already inseparable, but from the moment that Des finally confessed to wanting more than friendship, we never spent a single night apart for the next five and a half years unless we were in completely different cities. I thought that our decision to not move in together after two months of dating was mature and restrained, though we essentially paid twice the rent to live together in two different apartments just a few blocks apart. We made our unofficial “uhaul” official a year later, moving together through a few shared houses with friends over the next four years.

Des’ birthday was October 27, and every year a box full of Halloween decorations from Des’ mom would arrive as a gift. I remember watching Des open large, exciting-looking packages to reveal piles of thready spider webs and plastic ghosts, or a zombie figure that lit up and played spooky sounds through a cheap tinny speaker. I never understood this tradition. It hurt me to think that this day, set aside to honor the person I most loved, was being overlooked in favor of a generic, commercial holiday. I learned to enjoy the influx of decorations once we moved to a trick-or-treatable neighborhood, but every year I would quietly hope that the large box would contain a little something extra, a little something to mark that this extraordinary person that I had found was indeed somebody to celebrate.

Des and I grew together like tree trunks planted too close, with different roots and different branches, but grafting in the middle in ways that will always stay grown together. We chose to grow apart, in order to grow, and applied to different graduate schools in different states to force ourselves to do so. Moving was a way to open a needed space between us, but even then, teasing apart our interwoven selves took years. So when Des told me, in our second year apart, that he was transitioning, it felt like pieces of myself were being rearranged without my input – did this mean that I had never had a girlfriend? As I cycled through casual experiments with mostly men over the next few years, I struggled again to believe in my own queer desires. Without that thing, that girlfriend of five years, to point to as evidence, maybe I was just a tired gay-until-graduation straight girl stereotype after all.

![]()

Des was there on July 21, 2018, when I married my current partner Reagan. We chose the anniversary of my parents’ wedding for our own, weaving our time into the memory of theirs. We had pieces of our parents’ wedding clothes sewn into our garments. A close circle of our family – born and chosen – came together to affirm our partnership in a homemade backyard ceremony.

Reagan’s birthday is June 21: the summer solstice, the longest day of the year, balanced on the Gemini-Cancer cusp. “That’s why I’m so crazy,” he says, laughing at anybody who takes themselves too seriously. It’s also a pride birthday, and Reagan is as queer as they come. Before me, he had partners who rejected the parts of him that dated genders other than their own – trying to push him towards the clarity of a gay/straight binary. Now, neither of us worry too much anymore about being queer enough, despite being in a relationship that might look straight to an outsider. We see each other, and are building our lives together to celebrate all the ways that we know how to love.

![]()

I will always remember Melanie’s birthday, though it’s been twenty-five years since I last spoke to her. August 5 arrives each year with nothing to mark it but the sense that, once upon a time, I grew together with a person meant to be celebrated on that day. I light a Yarzheit candle every November 21 at sundown, and think of my grandmother’s flame flickering every April 1. I wonder if Des still gets boxes of spider webs, and I wonder if Ilana remembers the year she moved her birthday by six months.

People talk about growing into the person that they are today. But I didn’t grow into myself, I grew into others, and back out of them again. I grew in and out of love, in and out of intimacy, in and out of loss. These movements are a different kind of time than one that moves from year to year. Each birthday I remember rearranges the ones that come before and after it, weaving backwards and forwards through my stories, which themselves are woven with other stories. Our own birthdays are supposed to mark our growth, but other people’s birthdays can be a better measure.🎈

Comments

This is lovely :)

Thanks Beth!

Thank you for opening up and sharing all of this. There are so many parts that resonate, but what’s hitting me hardest is the way you describe how people can be the center of your universe and still drift out of it. You have such a nice way of considering the past from a distance while the emotions you felt remain present, if that any makes sense. I really liked this!

There’s definitely a very present sense of the past in there. Thanks!

Micha, this is incredible. Thank you for putting it into the world.

<3