June is LGBT Pride Month, so we’re celebrating all of our pride by feeding babies to lions! Just kidding, we’re talking about lesbian history, loosely defined as anything that happened in the 20th century or earlier, ’cause shit changes fast in these parts. We’re calling it The Way We Were, and we think you’re gonna like it. For a full index of all “The Way We Were” posts, click that graphic to the right there.

Previously:

1. Call For Submissions, by The Editors

2. Portraits of Lesbian Writers, 1987-1989, by Riese

3. The Way We Were Spotlight: Vita Sackville-West, by Sawyer

4. The Unaccountable Life of Charlie Brown, by Jemima

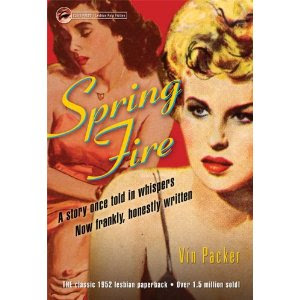

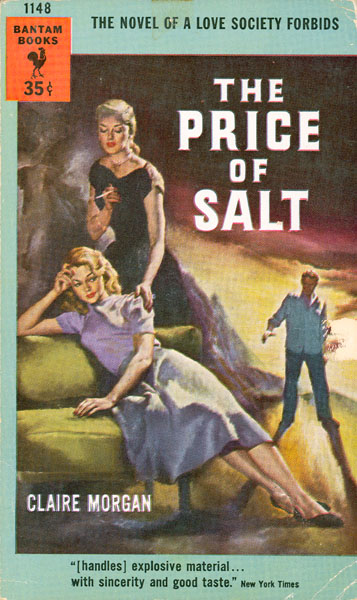

5. Before “The L Word,” There Was Lesbian Pulp Fiction, by Brittani

![]()

For the most part, “now” is usually better than “then.” As down as we may get and as mean as people sometimes are, being a homo in America is as easy as it’s ever been and not yet as easy as it will be. Past struggles have created a lot of different things. Things that come from sadness, triumph and experience. Often times they are beautiful. At times they are depressing. And other times, they are lesbian pulp fiction. In Post WWII America, the sexual posture and gender roles of women in America became increasingly important. Gender binaries reemerged with alacrity in an attempt to undo the “damage” done during wartime.

Clearly not interested in the heteronormativity prescribed to all women, queer women began to form their own identities in anticipation of liberation. To aid in this venture, lesbian pulp fiction entered the realm of paperbacks (accompanying mystery, westerns, and other subgenres). The paperback books sold in drugstores, gas stations, magazine stands, and transportation terminals. Available at a low cost and easy to hide, the paperbacks soon rose in popularity being consumed by straight men and queer or questioning women alike.

These sensational fictions helped create a community (albeit in a problematic way) for queer women while perpetuating internalized homophobia and saw some of the earliest invocations of the double standards of acceptance straight men often have for lesbians. Queer women were desperate for images of themselves in popular media. The 1934 Hays Film Code banned homosexual depictions in movies until 1962 and standards prevented such scenes from occurring on television shows. This lack of media and cultural representation led to a surprising avarice for the pulp fiction novels that were readily available in most large towns or cities.

It’s unclear how this material, certainly unaligned with American mores of the time and around the time of the Lavender Scare, initially went under the radar but many attribute it to the lack of respect for paperback publishers. With no attention paid to literary merit, the stories were of little concern. Once the genre became a hit, there were too many to police. It was impossible to tell the true content of the book from its cover because many books began to mimic the covers of lesbian pulp fiction in order to deceive consumers. It’s kind of like how movies with similar titles and plots will come out on DVD at the same time as something that was a hit in theaters in hopes that people will mistake the knock off for the popular title.

The covers did not only lure the reader in with images, it assured male readers the story was safe. The blurb on Twilight Girl said the book was meant for anyone who wanted to curb the “hidden lesbian contagion.” Third Sex marketed itself as a “study of society’s greatest curse: homosexuality.” Though lesbian in action, the women on the cover did not show any of the telltale signs the heterosexual male readership assumed of lesbians of the time. If you think the scope of what people expect of lesbians now is slim, imagine how limited it was then. Even though a woman was giving serious bedroom eyes to another lady, it was ok because she didn’t “look” like a lesbian.

Another reason the books evaded censorship was because the lesbian characters often returned to heterosexuality, committed suicide, or went insane. These books were Lost and Delirious before Lost and Delirious. If homosexuality was reprimanded, then supposedly the readers were not threatened or influenced. Of the books that ended in this way, many involved gratuitous sex scenes. It’s the give and the take, I guess. Since the books gave the idea that lesbians could be corrected, straight men went to bars looking for femmes to sleep with. The threat to their manhood came from masculine presenting women and as their supposed sexual competition, some straight men made it a point to “steal” their partners.

The novels complicated the stereotypes of the women being referred to as gender inverts. Abiding strictly by the stereotypes would have made the books less palatable. In this concession, the characters showed some diversity that actual lesbian communities had yet to embrace during this time of the harsh butch/femme dichotomy. The return of gender divided labor and feminine domesticity (which was accompanied by sexual ideologies) did not only affect the heterosexual world. Post WWII lesbians were less willing to present themselves differently with their families and coworkers versus with fellow lesbians. This unwillingness to live double lives enhanced the role-defining behavior. Since the pulp characters did not fall strictly along the butch/femme lines, it helped queer women open their eyes to different types of presentation.

As much as they stirred internal homophobia, they caused many women to confront the stereotypes as something that they did not identify with or believe. The stories listed many reasons for women straying from the heterosexual path and ways to spot a lesbian: athleticism, bad relationship with parents, no parents, sexually abused, depression, short hair, alcoholism, ugly, victim of incest, and having a unisex name. Often overlooked are the way the books treated bisexuality (poorly of course). Questioning or bisexual women were painted as lascivious and oversexed. Also, most of the heterosexual relationships involved hateful, physically abusive, or sexually abusive men. These books kind of made everyone look like assholes, to be honest.

Lesbian pulp fiction complicated the butch/femme history of the era, challenged the rampant stereotypes of lesbians, and provided representation for questioning and queer women who could not access the bar life of queer communities. The unfair and negative aspects of the plot lines and characters were accepted by queer women because the fact that publishers were willing to print stories about them gave many women the courage they needed to build the communities the characters lacked. It also encouraged women to decide what should be true and false about their communities. So let these books be a reminder to you. These shitty stepping stones are sometimes necessary to reach positive representations. Our 50s and 60s will someday be someone else’s 50s and 60s, ya know. Often times there’s a disconnect between representations and reality and though I don’t think shows like The Real L Word will later be reclaimed by lesbians and feminists like these books have been, I have faith that they will lead to something better.

Comments

Since I have been up all night long writing a graduate paper about censorship of lesbian fiction and the relative success of pulp novels in avoiding it, this article is extremely relevant to my interests.

Also noteworthy – it wasn’t just trashy (no judgment!) fiction marketed to pulp audiences. A paperback edition of The Well of Loneliness that was given a lurid, pulp-style cover sold around a 100,000 copies a year throughout much of the 60s.

And now back to work.

Before The L Word there was…peace in Middle Earth

Irene Chaiken: purveyor of lesbian sex to the tvs of straight men and responsible for the war of the ring.

You need to watch Forbidden Love!!!!! It is a National Film Board of Canada documentary about lesbosexual life in the 1950’s with people telling their stories interspersed with the re-enactment of a lesbian pulp fiction novel. Can I get a whatwhat?!? They talk to a woman who wrote lesbian pulp fiction and they all talk about the role the novels had in their lives. It’s probably the best thing I have ever seen you guysss. It’s also probably the best thing you’ve never seen.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FQVEmo4vzkQ

This is amazing.

ohmygod SECONDED! i remember watching this in my history of feminism in canada class in second year wmst and having all kinds of tingly feelings….

Wait, there was life before the L Word?

i love the beebo brinker series…it’s lesbian pulp fiction at it’s best.

My first and only encounter with lesbian pulp fiction was when my awesome mom bought me Odd Girl Out by Ann Bannon (http://www.amazon.com/Odd-Girl-Out-Ann-Bannon/dp/1573441287). I didn’t love the book, but it was interesting in a queer-history way. Thanks for the background!

I have a secret fantasy in which I’m browsing a thrift store and stumble upon a whole box of lesbian pulp fiction. They may make everyone look like assholes, but I still want them. A whole box full of them.

http://www.strangesisters.com/

Oh, I think I love you.

The Beebo Brinker Chronicles are definitely worth a mention… they’ve also been adapted into a contemporary play!

it’s the give and the take.

brittani you are one of my favourite writers on this site. i mean, i am fascinated by this topic anyway but your article is SO well written and readable. thank you so much for posting! i really love that you brought it home with the comment that shitty representations can be a big jumping off point – an important fact that i think we forget sometimes when we are so hungry for something better. anyhow. thanks thanks thanks! xox

No, thank you! You spelled it favourite and now I feel second hand classy.

maple points for meeee

[…] Some of the novels were pro-lesbian, and promoted positive ideas about the women-loving-women(WLW) culture. Most, however, catered largely to the myths surrounding lesbian deviancy and used stereotypes to tell their stories. The novels worked prescriptively, offering readers markers to detect a lesbian and hints of why a woman may have been forced to stray from the heteronormative path: “athleticism, bad relationship with parents, no parents, sexually abused, depression, short hair, alcoholism, ugly, victim of incest, and having a unisex name.” (Autostraddle) […]