To the boys who get called girls,

the girls who get called boys,

and those who live outside these words.

To those called names

and those searching for names of their own.

To those who live on the edges,

and in the spaces in between.

I wish for you every light in the sky.

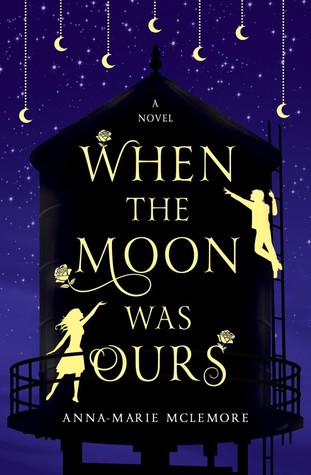

The YA magical realism novel When the Moon Was Ours opens with this dedication by its author, Anna-Marie McLemore. And so begins the story of Miel, a queer Latina teen, who fears pumpkins, has roses growing out of her wrists, and appeared one day inside a very old water tower; and Sam, a transgender Italian-Pakistani boy coming to terms with his gender.

“To everyone who knows them, best friends Miel and Sam are as strange as they are inseparable. Roses grow out of Miel’s wrist, and rumors say that she spilled out of a water tower when she was five. Sam is known for the moons he paints and hangs in the trees, and for how little anyone knows about his life before he and his mother moved to town.

But as odd as everyone considers Miel and Sam, even they stay away from the Bonner girls, four beautiful sisters rumored to be witches. Now they want the roses that grow from Miel’s skin, convinced that their scent can make anyone fall in love. And they’re willing to use every secret Miel has fought to protect to make sure she gives them up.”

When I first heard of When the Moon Was Ours, I was thrilled. Anna-Marie is an incredibly talented writer, a kindred soul in the book community, and I was blown away by her debut novel (The Weight of Feathers, 2015). There something deeply personal about the way she spoke about this new book, about her experiences being thrown out of religious communities, the discrimination her trans* husband and his trans* siblings face, and how it all tied into the purpose for and power behind When the Moon Was Ours. Thankfully, it more than lives up to the hype. I’ve been championing it since early this summer when I received an advanced reader copy from a conference I attended.

As queer, Southern, woman of color who always knew something was “different” about me, always noticed how my eyes lingered on girls just as long as boys, but was always aware that being queer wasn’t how things were done “in these parts” (even if no one told me that so plainly), I’m always looking for books that my younger self desperately needed. Books I can hand to my thirteen-year-old sister, who also struggles with anxiety, books I can recommend to others who seek out religion yet struggle with their vilification by their own religious community, books I can read now and reflect on the unsaid things I witnessed and learned growing up. I’m never one to lie and say that books alone save a person’s life, but they can give meaning, give understanding, give a vocabulary… a language through which to speak and understand oneself. When the Moon Was Ours is one of those powerful, precious books. It not only touches on qpoc life and gender roles and social constructs, but it beautifully and brutally explores what it means to be a queer teen of color in a world constantly rejecting and defining who you should be. It explores the very personal ramifications and effects of those rejections and definitions and what it takes to truly come into oneself, accept oneself, and ultimately redefine and stand up for who you truly are.

I appreciated how McLemore didn’t give a one-sided, paper-thin view of qpoc teen life. Where so many books focus on gender at the expense of race, culture at the expense of how that plays into sexuality, and queer boys at the expense of queer girls, McLemore sought to explore qpoc life in all its complexities. As she said in an interview for the National Book Award Foundation, “[When the Moon Was Ours] is for those like me who grew up or is still growing up believing that, because we are of color, because we are queer, because we are both, the world will not allow us any story but the one it has already written for us.” As McLemore goes on to say, “I wrote this book to be one more voice reminding us that our stories are ours, that we deserve our own fairy tales.”

I love it when stories are so deeply rooted in a place and in culture. In When the Moon Was Ours, there are the moons Sam draws and hangs to comfort Miel who is desperately afraid of pumpkins, which totally sucks because no one should be afraid of pumpkins, but also because the book is set during the Fall. There’s the La Llorona folktale McLemore weaves throughout as well as the little yet significant details like the Mexican and Pakistani foods throughout and various other cultural signifiers. The woods, the Bonner family’s farm… all of this come together to make an already magically infused book even more magical.

Then there’s the central role that family plays in the book. It’s my favorite gripe that in YA novels, families are often nonexistent, which is indicative of publishing’s very white nature. This is not to generalize or simplify, but when talking about upbringing there is a similar thread between my poc, especially my qpoc friends, that we don’t share with our white counterparts. Respecting one’s elders was one of the central tenets of my upbringing, even if one’s elders never respect you or see you for who you are. I never would’ve talked back to my parents or been allowed to “sneak around and go on my own adventure” (which is why I loved SNL’s Stranger Things skit during the episode Lin Manuel Miranda hosted). My mother was queen, and ultimately it was her I was most afraid of when I came out. For queer communities, but especially qpoc ones, family is often what you make it. I loved the Bonner girls, four sisters who’ve only always been seen as one entity. Despite all their faults, they are in many ways fighting desperately to stay together, to keep their powers over men in a world that likes women powerless. There’s Aracely, Miel’s guardian who takes her in and raises her after she pours out the water tower. Aracely is a curandera who pulls lovesickness from people at night, and doesn’t flinch when called bruja, a witch, by those same people during the day. Sam’s mother, who accepts the tradition of bacha posh Sam has adopted, “a cultural practice in parts of Afghanistan and Pakistan in which families who have daughters but no sons dress a daughter as a boy. The daughter then acts as a son to the family. As an adult, a bacha posh traditionally returns to living as a girl, now a woman.” I love how she both accepts and rejects tradition and leaves the decision of who Sam is and wants to be to himself. And finally, Miel’s mother who loved her but also feared what she could become.

These are family members we can understand. These are family members within my own and the families of my queer friends, many of which I met when I was student at Wellesley College. (In fact, what I loved most about my college experience was how all of us felt so very comfortable to question and explore every part of ourselves and were always a family, first and foremost, to each other.)

As person of color, more specifically as a queer person of color, and even more so as a queer woman of color, I often deal with an inner struggle of awareness. These are words I borrow from Gloria Anzaldúa, a queer Chicana poet, writer, scholar, and feminist theorist. I first read and drank in Anzaldúa’s words in college. She armed me with a language through which to speak my existence and a warning that before even attempting to change the world, I must first accept myself. I happened to read her work at the same time I read DuBois’s The Souls of Black Folk where he talks about the two-ness, the double-consciousness one feels as American and black. When the Moon Was Ours is such a powerful testament to queer love, love for yourself and another. It speaks to the importance of coming to terms with your “two-ness,” claiming your name and thus yourself — an important part of poc and trans histories — dealing with your inner struggles, and ultimately loving yourself.

It means a lot to see the mainstream appeal, love, and respect for this book: it’s won three starred reviews in review journals and was longlisted for the 2016 National Book Award for Young People’s Literature. Qpoc experiences don’t need to be whitewashed in order to be understood. When the Moon Was Ours is a love letter to qpoc teens everywhere, from its dedication, to the Andrea Gibson quote on the following page, to its very last line. I’m so very thankful this book now exists in the world, and I cannot wait to read what Anna-Marie McLemore writes next.