The thing about coming out is that it doesn’t happen all at once. It happens in stages. When I first said I was into girls out loud with any confidence, I was eighteen standing on a beach in Monterey after a rugby tournament. Before that I had known I was into women for about a year but had no idea what to do with that information. I had just moved to Sacramento for college and was on my own for the first time in my life. It had taken me joining a women’s rugby club and meeting people my age who were gay that led to me being more comfortable with how I felt. Coming out at that time was easy because I was so isolated, far away from my family. It’s easier to deflect prying personal questions over the phone than face-to-face.

It wasn’t until my early twenties that I came out a second time, and told my family. After college I moved to the East Bay, just outside of San Francisco. I got an internship for a gaming website which didn’t pay, but was really exciting. One day I was called away from my interning duties and asked to write something about one of my favorite video game franchises, Mass Effect. There’d been an article criticizing a recent promotional campaign getting people to vote on what the box art for the female version of the protagonist should look like in the sequel. Since the article had been written by a queer woman, I was asked if I wanted to write an article in response to it. It was my first opportunity to write an editorial piece — but writing it also meant I would have to reveal who I was in a very public forum for the first time. I made the decision to write the piece drawing from my own perspective and the day the article was published I called my parents and came out to them. They’ve been divorced nearly my entire life so that was two phone calls and a double dose of anxiety. Even over the phone it was terrifying, but it was a huge relief.

At the time, I felt like that was it. I was out, and from that moment on things would be easier, no challenges, no roadblocks, nothing to hold me back. For a long time that was true. I felt more confident writing things from my point of view as a gay woman and felt a general comfort existing in the world. But in my late twenties that I realized something was still not quite complete. Although I was content with who I was, something was off, a thing in the back of my mind I couldn’t put a face to yet. The things I should have an interest in didn’t interest me. I tried dating apps for a while and never met anyone I truly connected with; I didn’t like going to nightclubs at all either. My sexual experiences ranged from good to bad just as much as anyone else’s but things were always slightly off. Nothing stuck.

I’d known about asexuality well before I identified as ace but I had never considered it for myself because I just thought I was too awkward or shy when it came to dating. I attributed my aversion to nightclubs and casual hookups to my social anxiety. Why else would meeting attractive strangers in dark rooms with strobe lights and deafening music not appeal to me? My foray into dating sites and apps was never really that successful either. No matter how nice someone was things didn’t click and most apps just felt like an extension of club culture. The whole idea of dating felt like a chore, and in a way, it still does. I also thought that my insecurities might be the product of sexual abuse I experienced when I was around the age of two. These things plagued my mind for years leading up to my thirties.

One thing that helped me come to terms with my ace identity was delving into the experiences of other asexual people online. Although I had known what it was, I hadn’t truly taken the time to listen to the experiences of people who were asexual and why they identified that way until I was questioning things about myself. Once I did, I realized many of the aspects of being asexual applied to me. There is also a website, asexuality.org, created specifically to educate people on the topic. If you still don’t understand it or may be questioning if you fall into the asexual category, I would highly recommend checking that website out. By educating myself with their resources and listening to other people’s stories I found online, things fell into place. I slowly began to realize that while I initially identified as asexual, what I was feeling was more inline with being demisexual.

“Demisexuality is feeling no sexual attraction towards other people unless a strong emotional bond has been established. This is often included in or paired with the graysexual category because demisexual people may essentially feel like they’re asexual when they don’t have that bond with anyone, and the bond typically takes a long time to establish.”

There are some who do not see graysexual/demisexual people as a part of the asexual community but I certainly don’t agree with that sentiment. Sexuality being a spectrum, we can’t expect people to fall into one neat category all of the time.

I wish these resources had been available to me growing up. The internet was barely a thing when I was going through middle school and high school. The idea of going online was a luxury and there certainly weren’t an abundance of articles or video content explaining what being asexual was at that time. As a closeted kid there was barely any representation of queer characters on television or movies that I could identify with growing up. Stumbling across Buffy the Vampire Slayer reruns felt like striking gold. These days you can watch compilation videos of the entire queer story arc of a show or binge watch an entire series in a day. Having had to scour and scrape for any drop of queer representation I could I’m grateful that a new generation has a broader range of sources for media and resources. Many of the things I’ve found helpful lately are short films and documentaries made by asexual people, explaining what it is and what their experiences are. Mainstream queer media isn’t necessarily delivering the goods when it comes to representing asexuality.

“Sex sells” is still a predominant adage in how things are marketed in the media. Once kids reach a certain age, things start to shift from stories of adolescence into stories about teenagers losing their virginity or aspiring to. I remember watching countless shows and movies growing up where having sex was the primary goal of the protagonist or at least a motivating factor in what they did throughout the story. I grew up with five boys during puberty — the year American Pie came out was particularly grueling.

It was difficult to escape discussions of sex even at church. During youth group one night our youth pastor delivered a candid speech about sex, saying how great it was and that we should all wait until we were married to have it. This idea of abstinence was another thing I drew upon to justify why I wasn’t asexual before I came to terms with it. Abstinence and celibacy are often falsely equated with ace identities because many people believe asexuality is anything that does not include having sex. In reality concepts of abstinence and celibacy are a conscience choice, whereas identifying on the asexual spectrum is more about your desires. Desires that are an essential part of who you are.

An ideal pop culture representation of someone who identifies on the asexual spectrum should entail an honest conversation about how that looks in an adult setting, whether it be through a romantic relationship or a platonic friendship. While there are asexual people like myself who identify as Demisexual, and therefore still feel a form of sexual attraction, there are many asexual people who have no desire for sex or romantic relationships, additionally identifying as aromatic. Often, those who express lack of sexual/romantic interest are treated as if they have a mental illness, so portraying those characters that way won’t help things. Many problematic story lines involving people within the LGBTQIA community have used the depiction of queerness as a mental disorder as a plot device. This is something we’ve recently seen recede a bit in the past few decades, but it has not entirely disappeared. There are few moments in media that have resonated with me as an asexual person over the past few years.

To date, my favorite step taken toward asexual representation in major media came from the science fiction role playing video game, The Outer Worlds, released in 2019. Parvati Holcomb is the first non-playable character you can invite to accompany you through the story. Her personal quest includes her having a crush on a mechanic in one of the space stations you visit. It is up to you to help her pursue this person, and if you do Parvati gets very candid about how people have treated her due to her asexuality. While she never says it out right it is very apparent that is what she is talking about and seeing that kind of representation was very rewarding. Your character is also a bit asexual by default, being that you can participate in many side quests with your companions but you can’t romance any of them. Outside of games there are only a few examples from television I think that are equally as meaningful, and no, one of those moments does not include Jughead on Riverdale.

In episode seven of the third season of One Day at a Time Elena and her partner Syd hatch a plan to get a hotel room so they can have sex. When Elena finds out that Syd has already had sex, she freaks out a bit and starts going off about her insecurities. When Syd goes to comfort her, they say “We can do it next month, next year. We can never do it if that’s what you want. No matter what happens, I love you”. If you’re looking for an example of how to speak to an asexual audience even when your characters aren’t ace, this kind of dialog is important. Sending the message that you can be loved without having sex with someone you’re in a relationship is an important message to send especially to a younger audience. There can be a lot of peer pressure on kids to have sex as they go into their teenage years which can put them in very harmful situations if they rush into things before they’re ready and trust the wrong people. It was nice to watch a scene where a character who had already had sexual experience was conscious of another character’s apprehension and did not put pressure on them.

Sex Education, a show that predominantly portrays intense sexual relationships, managed to include a meaningful asexual storyline in its most reason season. When Jackson, the most popular boy in school, is cast as Romeo in the school play, Florence, who plays Juliet, is feeling pressure from her cast mates to put the moves on him. She seeks help from Otis, the main character, who dispenses sex tips for a nominal fee. Florence tells him that she got involved with the play because she thought it was all about love but in reality, it is all about sex and she doesn’t want to have sex.

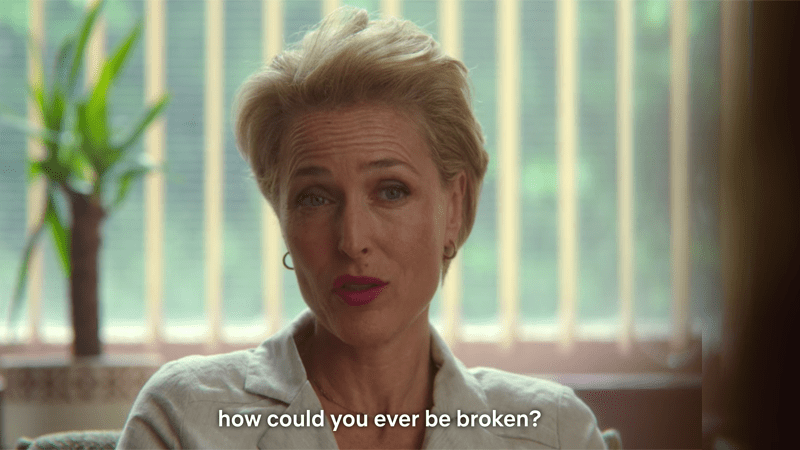

Otis tells her to go at her own pace and maybe she just hasn’t found the right person yet. This advice falls flat for Florence and after more run-ins with her castmates prodding her to try and sleep with her co-star she seeks out help from Otis’s mom, Jean Milburn, a sexual therapist played by Gillian Anderson. When Florence tells Jean that she feels broken because she does not want to have sex Jean takes the opportunity to educate her, and in turn the viewers, about what asexuality is noting that it is a valid sexual identity. Jean also goes on to deliver a line that helps Florence come to terms with her asexuality and also serves as an example of what messages should be sent about sex in general. “Sex doesn’t make us whole. And so, how could you ever be broken?”

Regardless of how asexual people realize who they are, their experience is no less valid than any other coming out story. Every asexual person has a moment when the recognition sets in. When they finally see who they are and the piece to the jigsaw puzzle they’ve been missing their entire life finds its place.

For me that moment was almost three years ago, right after I’d turned thirty years old. I was walking along an elevated sidewalk overlooking the Las Vegas strip holding a giant alcoholic slushie. It was my second year attending ClexaCon and I had been lucky enough to find two friends to room with that year, whom I’d met through the convention. We had found a bartender who poured quite generously and made our way around town laughing and sharing in the feeling of bliss that comes from having spent a day celebrating the queerest shit that made us happy. It is a memory I hold very dear especially now, in these uncertain times of self-isolation.

We had been discussing our experiences at the convention as well as things we were excited about on television and film coming out later that year. Earlier at the convention, we had befriended a girl who we’d met in line waiting for something. She was cute and she and I had arranged to meet up for breakfast that morning which had been nice. My friends and I discussed it on our walk and it was pretty clear I kind of liked her as well, which led to some discussion of me seeing her again during the convention. It honestly was the furthest thing from my mind in that moment and it got me thinking.

This is what people are supposed to do right? Hit it off with someone they meet on vacation and hook up? She was cute and nice so maybe I should pursue it more, right? None of that seemed very important to me at all because it wasn’t what I wanted. That was when I uttered out loud, words I had been silently repeating in the back of my mind for nearly a year.

“I think I’m Asexual”

There was a short pause as my friends let the news settle. It didn’t take long for them to express their support and the fact that it was just something about me they accepted felt incredible. We stood in that spot for a bit longer, admiring the sight of the busy streets of Las Vegas at dusk.

I closed my eyes, and for the first time in my life, I was completely myself.

Comments

thank you for this, Jessica. i think queer communities are often so focused on de-stigmatizing queer sex and desire that it can feel like there’s not much space made for de-stigmatizing not wanting sex at all, or accepting that as 100% valid and real without framing it as a psychological malfunction or hang-up to be overcome. thank you for sharing your story here. <3

It’s an honor getting to share my story here. I’m very thankful for autostraddle’s existence, especially these days. <3

This is fantastic, Jessica! Thanks so much for writing this. Also, I immediately had to text my best friend and ask her if she was secretly you, because she is a queer ace gamer fandomer and I LOVE seeing her represented in the world. <3

Nice! Glad to know there are more of us out there.

Could I quote this line? It’s perfect for an project on asexuality I’m working on!

Also, promise to issue full credit of course.

Totally fine to site as a source. Good luck on your project!

Great article. And YAY for being completely yourself! Thanks for sharing. xxx

Your story sounds a lot like my story. Thank you. Sometimes it’s still hard not to feel broken, even now that I’m in my thirties. I feel like I am constantly given the message that there is something wrong with me, and on bad days I almost believe it. More representation is so important.

Feeling broken is definitely something I’m familiar with too. From what I’ve read and seen of other ace people sharing experiences online that’s not an uncommon feeling so you’re not alone in that. I’ve found that being more open about it and learning about other people, like yourself, with similar experiences helps a lot.

I love love love seeing ace stories on AS. That “aha!” moment of realizing it is wild. It’s been years and I’m still like oh yeah, allo people experience things differently.

It always makes my heart happy to see ace stories on AS <3 Thanks for sharing this!

Thank you for writing about this and sharing your journey. Sex has always been a puzzle for me, I oscillate a lot between interest and indifference. I feel like there’s room for me to be fully myself in the asexual spectrum.

That’s my experience too – I don’t know if I’ve ever seen it articulated before.

I clicked on this SO FAST! I’m currently burying myself in ace books and podcasts and feelings, so thank you.

What are your favorite ace books/podcasts right now?

Thank you for this, as a demisexual lesbian. I felt this way for a long time – I felt like there was something wrong with me, something broken, as I watched all my friends (most of whom are straight too) talk about sex/dating and me always so scared to tell them I felt like all this was a chore UNTIL I crushed on someone who I had an extremely emotional bond with and that was always so rare.

Personally, there were a few moments in TV that made sob because they mentioned asexuality (that wasn’t mentioned here!) Todd’s coming out in Bojack Horseman, and also Big Mouth’s Spectrum of Sexuality song where they sing, “Now should you require romance, To get you into no pants, Then a demisexual is what you’d be”. Hearing the word “demisexual” on TV was a huge moment for me and I cried and texted my friends.

I admittedly have not gotten into Big Mouth yet which I will make up for soon. I’m glad they included that, an important part of all this is saying the words out loud and explaining what it means. Even a mention in a song like that is really cool. I loved Todd’s story line on Bojack. I remember as it was happening it felt surreal because they were so open about it on the show.

I’m 36 and came out as demi this year, after being out as bi since my teens. I also just blamed my anxiety for not wanted to use dating sites or go to clubs. I thought I couldn’t be demi at first cos I’d had casual sex in the past, but looking back all of them were at the height of my mental health being trash and almost always while I was drunk or high. It was actually seeing so many of my friends talking about missing sex during lockdown that finally made the penny drop!

I was literally just thinking this morning about how I wished I could read more articles about asexuality on Autostraddle and then lo and behold, this article appears! I’ve been reflecting a lot lately about what I want (and don’t want) and where I fit on the sexuality spectrum. I too have often felt broken or incomplete, and that line in Sex Education really hit me hard. It was the first time I’d ever heard anyone say something like that, and I really needed to hear it. Thank you for writing this, Jessica, and thank you for publishing it Autostraddle. I hope to see more pieces like this here.

Thank you so much for this article! I identified as asexual for the first decade of my adult life but always felt more comfortable in queer and lesbian spaces, and there has always been a lack of writing that encapsulates both those identities. Now I’m a year into my first sexual relationship with an amazing woman I want to cherish forever, and I’m honestly not sure how I identify anymore… But continuing to see representation of all parts of my now and former identity is heartening. <3

I read the title and my heart skipped a beat. I think it’s because it hit me that not only does being gay AND asexual doesn’t get represented in the media, it doesn’t get written about, either. You made me feel more seen and I’m happy for the both of us.

Thanks for this.

Ah, I feel this so hard. It’s amazing how similar so many of our stories are. Makes me wish that it didn’t take so many of us so long to figure out that there’s something different going on, but I guess that’s what we need more representation for. Great article, always love to see people talking about asexuality, and especially how it intersects with other forms of queerness.

Thanks !

I don’t know what I identify as still; I’ve come out so many times, and everything feels wrong, including saying nothing or no labels. But I definitely feel queer, I just often feel that I’m not welcome or seen in queer spaces where so much is about sex and/or relationships. I think I like Autostraddle because it’s always had so much beyond that, and a lot of the most heavy relationship stuff is in the context of fandom. Anyway, I’m grateful to see asexuality represented here. There’s so much variety across asexuality and aromanticism, and so little representation across media already, having more is really meaningful.

I love this article. Thank you

This has given me so much to think about. I’ve come out as bi twice now – once in my early 20s and then a 2nd time in my late 40s, after I realized I’d unintentionally bi-erased my identity.

I realized a couple years ago that I might be demi – reading queer romances with ace and demi protagonists had me going, wait, there’s a name for this? And having a queer therapist really helped confirm it. But I’m not sure I need or want to come out a 3rd time in my early 50s.

Unlike many demi folx, I never really felt like I didn’t fit in – probably because I tend to assume that whatever is going on in me is fine and normal (which serves me pretty well, except when it doesn’t).

I guess I just assumed that all my school friends lusting over various teen heartthrobs just randomly picked someone so they’d have someone to talk about it, as I did. And I definitely remember being celibate for 3 years in my 20s and wondering why other people seemed to make such a big fuss about not having sex because it was really no big deal to me.

I tend to cycle between being completely uninterested in sex and really interested in it. I kind of assumed that that would even out once I was in a LTR, but after 20 years with my husband, my interest in sex still fluctuates pretty widely.

I’m curious if any other bi+ demi/grayace folx notice a difference in how their sexual attraction works w/r/t gender. I think I may be bi-romantic and demi-sexual but I also think I’m less demi with women. I have an actual physical type when it comes to women but with everyone else all I care about is emotional connection and chemistry. I still need that emotional connection to women but I definitely notice women’s bodies in way that I don’t notice men’s.

Hi! I love this. I feel like a lot of my queer friends have their identities locked down early, and I think it’s super helpful to know that others are still figuring it out throughout their entire lives.

Anyway, I have a way of thinking about the intersection of ace-ness in conjunction to queerness you might find useful. Everyone talks about attraction as being on a spectrum. Think of this as an x axis with bi at 0 and homosexual and heterosexual on opposite ends, at 1 and -1. Then put libido on the y spectrum with asexual and very sexual at 1 and -1. That gives you so much room to place yourself, and it doesn’t isolate gender preferences from sex drive. On top of that, you can think of it as a function over time, and the little point that is you can ping pong all over the place. Sexuality is more than a spectrum. It’s a function over time on a space that is, at minimum a two dimensional graph. On top of that, you may not even be a point. You could be a full shape. Give yourself space. Sometimes that’s all we need, even in abstraction.

it’s really beautiful to see this article on autostraddle! i remember searching “asexuality” on this website four years ago, when i was coming to my ace identity, and being disappointed to see so little turn up. seeing more and more articles by and for ace people on a queer website is so exciting because it makes this website and community feel more like home.

this story is gorgeously written and resonate, even from the title, “coming out twice.” it feels so true the ace experience. many queer people come out to their family and friends, but there’s a unique strangeness to having to explain your truth twice to people who think they already understand you. so happy to see how this story captures that sense of anxiety, as well as the pure joy that comes with being comfortable with yourself and your desires.

thank you so much for writing and sharing your experience!

I think this might be my favourite ace article I’ve ever read. Thank you for sharing it.

Thank you so much for this article. I’m ace & bi and I totally get how being taught about abstinence might muddle the realization (I thought I was just a really good Christian, lol). Every piece of representation makes me so happy! <3

Yes! I was like “oh, God’s delivered me from temptation this way.” And then it turned out that I was a lesbian, and also probably gray/demi and ohhhhhhhhhhhhhhhh. Oh. I figured that out at 26 in a coat closet with the face of a girl I’d known for years pressed up against mine and so many things clicked into place.

I’ve been a little slow to catch up on articles/comments lately, but I still want to share how much I loved this piece! Your writing touched something in my heart as I read, especially the experience of multiple coming-outs. Thank you!

Also, I haven’t yet watched Sex Education (that quote!) and didn’t really get into the early seasons of Bojack Horseman, so I think I may need to give those shows another chance.

Hello, thank you so much for writing this. As a fellow demi person, this means a lot.

Echoing what some people above have expressed, it feels great to see articles about asexuality/greysexuality on Autostraddle!

Awesome.. Really such a great article.. Thanks.