It’s late June as I stand on my girlfriend’s balcony in Stockholm overlooking the paths that wind around the collection of apartment buildings. I am momentarily frozen in fear and sudden-onset nausea by a thought that seems mundane.

“What’s going to happen to my plants when I’m gone?”

This was the first time I had allowed myself to complete a thought about leaving since my arrival in Sweden two months ago. The first time I allowed reality to sink in again. After several weeks of refusing to talk about it and shutting down conversations on the topic of our limited time, the realization was here to stay. Of course, I knew she would take care of my tiny herb garden just as well as she looks after me. She’s good like that. But I would leave and they would grow up from their seedling states and by the time I saw them again, they would be unrecognizable.

We can only see each other for a maximum of three months at a time due to Swedish and United States visa restrictions. A day longer, and we’re at risk for deportation. If deported, we won’t be allowed back in the country for years. January through March, Agnes had saved up her money working a day care job to stay with me and my roommates in upstate New York. June through August, I stay with her in Stockholm, making a living writing from home.

It’s not as if she’ll be gone from my life when I leave Sweden. We’ll still talk every day: about the daily occurrences in our lives, the people in them, offering support to one another to fight away all the deep dark fears we both have. But when we make that change, and my girlfriend goes back to living in my phone like Samantha from Spike Jonez’s Her, things will be radically different.

To date long distance then live with the other in person is to be in two versions of the same relationship. One wishes desperately for the future and is fueled by daydreams of the past; the other tries to make every waking moment something special and ignores the fact that time is passing, whether we like it or not.

One of my first memories of being with Agnes is also one of my favorites. We had been out drinking in an out-of-the-way pub in Gamla stan. I had been denied entry into several bars because bouncers thought my New York State ID was a fake. But this particular pub had barely given it a second look. Several Coronas, maybe a shot or two later, our group was fucked up and marching through medieval alleyways in early January. Agnes walked away from me, my girlfriend at the time, and a mutual friend of theirs. She said nothing, knocked over a Christmas tree onto the cobblestone, and started dragging it behind her. I ran up to her, overjoyed for some reason, thrust my hand into the pine needles, and carried the other end. We arrived at a convenience store several blocks away and she gently set the bottom on the ground and I helped ease it against the wall. She went into the store and I stood outside beaming, admiring how perfect it looked there.

When we’re gone, I tell her this story at least once a week. It’s a story that I tell mostly for me, because whenever I talk about it, I remember how good I can feel next to her. We both do this, tell stories about the good times to keep going until we get to see one another again. Even now, when we’re living with one another and have been for months, I’m still in the habit of saying “Remember when…” and she responds, “Well yeah, that just happened yesterday.”

There’s a pressure that enters the relationship when we’re cohabitating; pressure to use up all of the time we have creating new memories, just to get us through the next stretch of absence. It’s worse for Agnes than it is for me; she has a clearer perception of the future than I do, and now that I’m in her country, she feels pressured to chart out our days so that each is its own fantastic journey. It becomes hard to just relax with one another and let that be okay, not knowing how these memories will hold up.

Our lesbian urge to merge is real. This underlying current of codependency that runs through our relationship increases when living in the other’s time zone. Some of the reasons for this are practical, like me not knowing how to get anywhere on the subway because I was too cheap to pay for an international data plan, so now she’s my constant navigator. Or the fact that we never really learned how to do laundry in the other’s country.

Add to that the constant feeling of time passing by, and the nagging fear that if we aren’t careful, it’ll be gone before we’ve had time to accept it. There’s no taking time out for yourself when time together is a commodity that’s constantly running out. We need to soak up every second when we’re together. While most couples feel like they have all the time in the world, we know that we don’t.

When our time is up I’ll spend a full day travelling, unable to contact her for almost all of it. There’s a special feeling of isolation in those hours that I struggle to define. I’ll return to my unbelievably supportive moms, and friends that have become my family through the years. The thought of being reunited with everyone is exciting in its own way, but I’ll be separated from my person. She will walk around a house full of things that I have touched, maybe find a forgotten shirt or two, and fall asleep by herself in a bed that still smells like me.

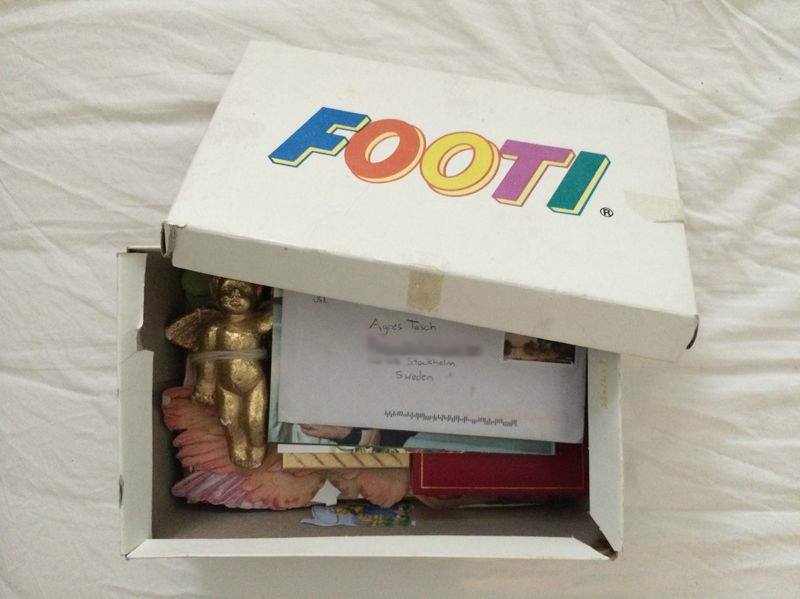

Every time, it’s a grieving process. There is no gradual change, no halfway point, just a day of radio silence then we go back to living without one another and telling each other stories over the phone. She’ll send me mixtapes, photos, bead bracelets and letters written on paper scraps. I’ll send her odd little presents, tidy letters and poems. Once, she sent me a book of Swedish poetry with notes about love and jumbled thoughts shoved in between the pages on multicolored pieces of ripped paper and sticky notes. Once, I sent her a poetry chapbook I made for her with pages ripped from my journal, red thread, pressed flowers, lots of glue and sturdy bits of the light blue softcover book where I first got published in high school. It helps to have something sentimental to hold in your hand.

The hardest thing about LDRs is the eventual discovery that another person, no matter how much you lie around pining for them and missing them, will not be the solution to all of your problems. It’s easy to project your issues onto the absence of someone significant in your life. To say, “If only she was here everything would be better.” The reality is, some things are better for me when I’m around her. But some things don’t change.

On the phone, we would argue about me being dismissive sometimes, or not present enough in serious conversations. I told myself that these problems were just issues when your only source of communication is Skype and Facebook Messenger. “When she comes here to live with me,” I thought, “These issues will go away. I can be physically comforting without knowing what to say.” Turns out, even in person I’m not always tremendously comforting. It didn’t occur to me that a hug might be the last thing someone suffering from tremendous amounts of anxiety might want.

We used to gossip with one another about petty issues with others, and now we have petty issues with one another. I have a constant, somewhat narcissistic fear that something terribly wrong has happened or will happen, and it’s going to be my fault. She’s the most emotionally intense person I’ve ever met and doesn’t use “compliment sandwiches” when asking me for something. This leads to intense arguments at least once a week, focused on the dishes, or turning the lights off, or my tone. These tend to end with us sobbing, holding on to one another, apologizing, explaining ourselves to the degree most would reserve for therapy and saying some incredibly endearing things.

The most important thing to remember about dating long distance: your issues won’t fly off into the sunset when you travel to your significant other. All the background issues get drowned out in the excitement of seeing your lady love for the first time in a long time. After a while of getting comfortable and getting past the shock, the relationship starts to evolve into something more. When you’ve gone so long without seeing the person, you’re able to appreciate the odd things that don’t come into play over the phone. These can be details like the kitchen lights constantly being on, post-workout stank, maybe even snoring.

The exciting thing about being in a long distance relationship is how everything about being near your partner feels exciting. How the necessity of constant emotional communication to keep things going despite the distance leads to a sense of closeness that’s hard to find otherwise. All relationships are beautiful wrecks in their own way, but the special thing about LDRs is the constant choice to keep working on a relationship with someone, feeling committed enough that you’re willing to cross oceans to be with them.

Comments

Thank you, Tierney. Every time my fiance leaves, I always gravitate to his clothes in the closet and keep smelling them. Dorky, maybe, but it’s easier to imagine his arms around me. Having a few thousand miles between us is heart wrenching. I practically live on Skype.

Ahhhh this is beautiful

This is lovely and I really appreciate it!

I loved this! Thank you.

Your phrase “How the necessity of constant emotional communication to keep things going despite the distance leads to a sense of closeness that’s hard to find otherwise.” rings so true to meee. I find that feeling both amazingly intense and horribly stressful. I have at last managed to settle with my LDR person and I still find that desperation and strong intention of wanting to be with someone very useful and fruitful. I actually wentfrom Norway to Sweden (Stockholm) so that we wouldn’t have to live by three month restrictions any longer. There’s a labyrinth of alternative imigration laws one as a European citizen (in this case your gf) can navigate, so drop me a message if you’re into knowing more about that. Cause 3 months fly freakin fast.

What alternative immigration laws do you mean? Are these like loopholes?

I guess, but very legitimate such ones! For example, if you and your gf are willing to live in any other EU/EES country, say Norway or Denmark (easy transition for your gf work/language-wise) she as a EU citizen has a right to bring you with her without having a certain income etc. etc. If marriage is not holy to you (or maybe if it is and you’d go for it right away) I’d reccommend marrying. We did. And three month limits are goooone. Might sound like a crazy plan, but to me it’s worth every effort :)

Loved this especially: “The hardest thing about LDRs is the eventual discovery that another person, no matter how much you lie around pining for them and missing them, will not be the solution to all of your problems.” It’s so obvious once you realize this, but getting to that realization is so hard sometimes.

“On the phone, we would argue about me being dismissive sometimes, or not present enough in serious conversations. […] Turns out, even in person I’m not always tremendously comforting.”

…To be honest, this sounds very familiar to me, and not in a good way. If this kind of theme recurs often enough in your relationship that you feel anxious, inadequate or ashamed of your perceived inability to provide comfort, you need to know that that is not an emotionally healthy dynamic, and it is not your job to make someone else feel good all the time. Especially if you start to feel bad yourself in trying to do so.

This is so beautiful and heart-wrenching and true. Thank you thank you.

Beautiful and so, so very true and insightful. Thanks for writing this.