The Morality Play. I remember it well from theatre history — a medieval theatrical invention wherein the protagonist represents humanity as a whole, and other characters represent good and evil. They advise or tempt the protagonist in turn. Their purpose was to instruct. As stories, however, they were didactic and clunky. Less enjoyment, more Lifetime Special shown in gym class to espouse resilience against danger and reinforce purity. In short, a plea with the audience: please be good.

Last month, I went to a giant writer conference and attended a panel about violence. Aside from what I do here, I write fiction. I write a lot of violence. Violence against women, violence against queers. Violence in the places violence likes to happen. Plus Maggie Nelson was on the panel, and y’all know how much I love Maggie Nelson. She talked about the risks of witness, of writing violence because it happens and depicting it because it shouldn’t go unnoticed. Of course, Nelson was talking about nonfiction. When I write about violence, I’m making it up out of my own head. I stood and asked the panel a lurching, bumbling question — has anyone else ever worried about representing violence against marginalized groups of people? On one hand, we need to represent the real social ills because we shouldn’t look away. On the other, when we normalize a narrative of violence against a marginalized population, isn’t that contributing to something larger than ourselves?

The first answer I got was to eschew all responsibility when creating a thing, because creating a thing is hard enough. That sounds right. That sounds fair. And shouldn’t women, queers, queer people of color, trans people, nonbinary folks — all those people who are not cis straight white able-bodied men — shouldn’t we get to just make narratives with abandon, too? But I don’t become a different person when I sit down to either make or consume my media. And I also couldn’t shake this weird other thing following the question around in my brain: we were talking about writing, at a conference about writing, so why was I thinking about video games?

I suppose the only answer is because I recently pitched a class on reading games as texts — we would read novels and play video games side by side, talking about the impact of gameplay on narrative. Because games are just another way to tell story — and the stories are getting better and better. I’d argue that many of the titles that gain real critical acclaim get there not only because of gameplay or graphics, but because of story. I truly believe video games are another way of consuming novels and short story collections, and that the tools and structure of traditional narratives still apply. They’re two sides of the same coin. The class didn’t get picked up, by the way. But I still strongly believe in the intertwined-ness of stories, games included with all the rest of the ways we figure out what it is to be a person. But in the case of games, with multiple outcomes and varying choices, the responsibility is two-fold: on the creator and on the player.

Five years or so, this might have been an essay about violent video games, coming down one way or another, trying to prove something that can’t be proven. For the record, I don’t think violent video games make people violent. I think people make violent video games because they are violent, and that is scarier. But the thing is, the dialogue has expanded beyond that. There are more options outside of Grand Theft Auto, and in a lot of ways the medium has grown up a lot. No longer solely gladiatorial in nature, we’re seeing a boom in what kinds of stories games can tell. And with that expansion, I’m personally seeing a lot of games tackle issues of ethics, games that directly interrogate the player’s sense of right and wrong.

Today, I spent a lot of time playing Undertale, by Toby Fox, for this essay. And I have been trying to write about Undertale for months. Maybe even a year, at this point. I have so many heart-bursting feelings about it, combined with slightly academic thoughts. For one, there are many ways you can play Undertale — the traditional video game way, where you kill things in your path to level up and gain points. Or the pacifist way: exist at level one for the entire game and figure out ways to talk to monsters, to convince them to spare you. There are many shades of grey in between.

For instance, there’s a mother figure present in the first area of the game. Her name is Toriel, and she’s sweet (if a little overbearing). The first time I played, I killed her. I couldn’t figure out the way around it, and I thought the game wouldn’t let me kill her. But it did. I felt SO BAD about it that, about half way through, I restarted my game entirely. I simply couldn’t continue in a world where I killed Toriel.

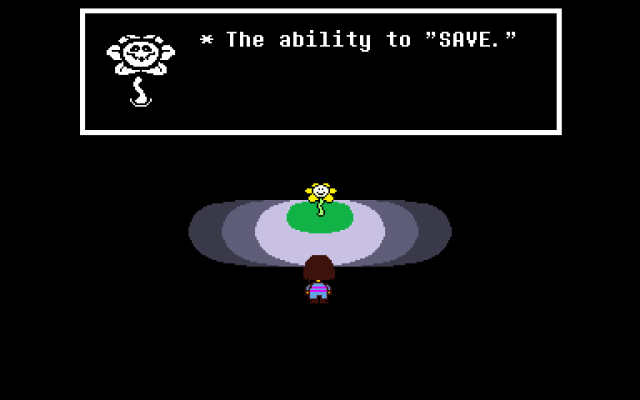

The game knows I did that. The game has told me so. “You murdered her,” a little evil flower said to me, “and then you went back because you regretted it.” The ability to save and go again, well. That’s a privilege, to shape the world like that. Says the flower. Fucking flower. Because yes, I did. That is exactly what I did, and Fox knew we would. Because he is banking on our morals. Because he is explicating to us another way to be a person. With the genderless protagonist, the protagonist named after the player, the game puts the player in its world. And the game doesn’t forget the decisions the player makes, even if the player tries to. It takes on the assumption that violence is necessary to progress.

It’s powerful. More powerful than any morality play could be, because it’s not didactic. The gameplay is both unique and nostalgic (the graphics harken back to adventure RPGs of yore). It features in its story the soul. The nature of the soul. And yet it does not feel instructive. Furthermore, it takes on a culture with a poor track record on real world violence, and there’s a subreddit dedicated to it. It won IGN’s PC Game of the Year in 2015. It’s safe to say that gamers are longing for the subversion it brings to the table, longing for reflections of alternate paths in life in the medium they love.

Other games tackle morality too, in ways only games can — The Cave, for instance, takes a rather Shakespearean approach to moral shortcoming. The Cave directly addresses you, the player, and even though you are controlling the tiny people in their beautiful worlds as they make very questionable choices, The Cave instructs you to watch and learn from their inevitable tragedy, their predestined bad behavior. But there is one thing you can do — you can regret. You can show remorse. And, spoilers, at the end of each playthrough, you can make those characters give back the thing they wanted most. My favorite one to play is the Hillbilly because his story directly deals with violent masculinity. He goes on a murderous arson rampage because a woman rejects him. You, the player, can enact his redemption by making sure he never goes on that rampage at all, that he takes the rejection like a person. All because you’ve seen the dark side, you’ve seen where it can lead, and you, the player, are making another choice. A better one. Whereas Undertale berates you for regret, says its not enough, The Cave celebrates it. But something interesting happens with Undertale nonetheless — Toriel is alive now. The player has learned in either case.

Games can do this like morality plays never could for many, many reasons — gorgeous art, seamless story and challenging play are all among them. But I think the most two most important moving parts here are failure and regret: the ability to see the outcome of the bad choice without any real-world consequence and then to select the other choice. And all this as the player, not necessarily as a built out character that you act out. All this as you. Games are growing up, I say. I cannot wait to see what’s next.

So how about you? What games in your arsenal tackle the player’s personal moral compass? Do you think this is as important as I think it is? TELL ME EVERYTHING NERDMOS.

Comments

Ali this is an exceptional piece. Thank you so much!

How far along are you in Undertale? Because you might want to reconsider that statement about the name.

MORE UNDERTALE SPOILERS AHOY

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Also there’s three distinct modes of gameplay. Pacifist involves you sparing/conversing to each monster and everyone stays alive at the end. You can’t really get there IMMEDIATELY though, there’s a particular someone that needs to die but then you get the chance to start over and do some extra legwork.

Neutral is if you have any kills along the way – depending on who you kill, the responses and endgame are different, but I believe the game encourages you to start over and go Pacifist.

Genocide/No Mercy requires you to go out of your way to kill every last monster. It’s an awful, boring grind, and at some point you get so OP that you kill even the bosses with one shot. You do get a bonus boss battle that doesn’t show up in the other routes, and you also get more backstory. However, the ending is not at all satisfying. It is gory, involves a lot of waiting around, and you just end depressed rather than accomplished.

A lot of people talk about how the game is purposely set up to shame people that go Genocide, but what I wish people talked more of was the relative “privilege”, so to speak, of going Pacifist. I actually stopped playing Undertale after a while because I am terrible at bullet hell and became extremely frustrated that I could not advance (I’m stuck at Mettaton but I wanted to quit even before Undyne showed up). I actually went Neutral because I felt like I didn’t have enough to defend myself – I’d die too quickly. Even on Pacifist you still have to play the bullet hell minigames and urgh I wanted to throw my computer so many times.

It made me think about how sometimes the people who are all “be peaceful! never be angry! non-violence all the time!” speak from a position of privilege, that they are rewarded for being nice – and how that’s not always true for a lot of marginalized people, whose niceness is still regarded as rudeness or aggression, and who feel pushed towards violence even if just for self-defense.

This is why I tell people, unlike every other website out there, one should read the comments on Autostraddle.

A friend of mine had a very similar read on the game, actually. I (like a lot of people!) got a lot out of the option to do the pacifist run and found it to be a really clever, unusual, subversive game mechanic (plus the ending is SO sweet, and the post-ending quest is super intense and awesome).

But I brought it up with him, and he mentioned that as someone who was intensely bullied all through his youth, it was pretty difficult / triggering for him to face monster after monster, most of which are actively attacking you, and you had to “be the bigger person” and figure out a way to disarm them that was basically doing ANYTHING except actually fighting back.

Which definitely gave me some much-valued perspective on the whole thing, even though I remain Undertale stan #56456.

I think it depends on why you’re doing genocide. I did it to understand a particular character relationship better, and I don’t regret it, though I reset after the really hard fight and watched the ending on youtube because I couldn’t bring myself to kill [spoiler character]. I know people who’ve done it because they’re fond of horror, and they didn’t regret it. The game asks if you want to have a bad time, and if you go “no, I actually do not want to have a bad time” and turn around, you get what you want… and if you go “yes I absolutely want to have a bad time” and keep going, you also get what you want. But if you approach the route feeling entitled to do whatever you want without any long-term consequences, despite the game obviously not working that way, then yeah, that’s not what’s going to happen here. Your mileage may vary, of course, but I never felt shamed.

That’s an interesting point about how pacifist is easier for people who are good at bullet hell. There are some measures in the game to make it easier for people who are willing to put in the effort, but just can’t dodge very well (if you’re still stuck on Mettaton and you haven’t found Tem Village, there’s something there that will help). I think Toby Fox could’ve done a little better (maybe some sort of invisible skill assessment at the start?) but it’s impossible to balance a game for all skill levels of players, especially when the pacifist route is supposed to require more effort than the neutral route. At a certain point, if the gameplay is impossible and not fun, then the game might just not be for you.

It definitely seems like some complicated things about privilege are going on between the protagonist and the monsters, though.

Get the Temmie Armor, it’ll help you survive those bullet hell sections.

H0i

I don’t recall if I have the Temmie Armor or not, but it doesn’t solve my terribleness :P

Well, it gives you some really nice stat boosts (including how much HP you regenerate, and how long you’re invincible after getting hit), so it’ll make it easier to get through the bullet hell even if you’re terrible!

But if you’re just done, you’re just done. That’s okay, too.

Ah, Undertale’s way fun. I won’t spoil anything for you (not sure how far you are) or anyone else. But I do highly recommend it for anyone who’s looking for something interesting to play.

For the rest, I don’t know. I know there are games where moral “stuff” comes into play, but I don’t usually think about it much outside of that particular game (or franchise/game universe/whatever). I guess I tend to play games more for escapism, so I don’t really want to think about the “real” world when I’m fighting the Lords of Cinder or Infected or robots or whatever. Though I don’t generally enjoy unnecessarily being a jerk in a game either.

That’s just me, however. =)

I haven’t played Undertale myself, but I’ve watched let’s plays of all the major game paths, and one of my favorite things about the No Mercy route is that at one point, a character directly tells the player that there are likely people who don’t have the nerve to make their decisions themselves watching the violence voyeuristically, from a distance. The game itself acknowledges the existence of let’s plays and the unique relationship with video games that they create, especially in the context of a game with such moral energy to its choices.

I wish your class existed, I’d love to take it.

My moral choices mostly come in the shape of Fallout, Skyrim, Mass Effect and Dragonage. All of which have detailed stories and far reaching consequences to actions. I have cried. I have mourned…I have loaded from last save.

It’s an awful lot of choosing how to play to prevent violence in my case. Like how do I make myself the most charismatic human to ever wander *insert land name here* so I can persuade my way through this situation. Obviously in those games there is always much violence against the enemies. But there are many many moral decisions to be made along the way, do you steal? If so are you all Robin Hood about it or just an asshole? I have avoided killing dragons because they were asleep and not attacking me. I have avoided killing dragons because I like their character and they’ve done nothing wrong…thus preventing me advancing the storyline. If there’s a way to complete something without killing someone and everyone staying chill I will find it…I just want ALL my companions to be the bestest buddies ever and to only do good. I’m a Hufflepuff folks, it’s my cross to bear.

The one occasion I have really slipped, and been gutted about it, is playing Life is Strange – (here follows deliberate vagueness to avoid spoilers) I just wanted that gay storyline so bad…more than I wanted to be a good friend, you know, and it felt very teenage which fits the age of the characters, but maybe I’m rationalising. The guilt was REAL. I will in all likelihood replay it and try to do the right thing, and have my cake and eat it, but I’ll always know I did that.

Honourable mention to Beyond Two Souls

*SPOILER ALERT*

I loved and engaged so hard with that little Ellen Page character, and her story of being different, and being weaponised because of it….up until I rage quit at being made to tidy my apartment for a guy to come over. My missus offered to play through that for me but I refused. Nope.

Have you tried Dishonored? There’s an achievement for finishing the game without killing a single person, which is absolutely possible (you just knock a lot of people out) and is really way more fun imo – I actually have not played the game in the traditional way AT ALL. Never killed a soul. And it was great! You are in some ways rewarded for playing the pacifist route, too – a lot of better outcomes (and you save a lot of $$ on weapons lol)

If you like sneaking around style games with a lot of storyline and a bit of magic, you should check it out. Just remember that F5/F6 (quicksave/quickload) is your friend, because you will definitely make mistakes. Especially if you play not only pacificst but also ghost (never killing anyone and never getting seen by an enemy)

The sequel is coming out soon too and the little girl character is All Grown Up and will be a main character, apparently.

I’m currently playing a The Witcher 3, which was rightly panned for the massive, constant, over the top misogyny present. I’m playing a dude character, which I dislike, and the women are largely sexy feminine temptresses (apart from your adopted niece/ward, but the fandom of dudebros have even tried to ruin that…ugh)

And yet. I just finished a long multithreaded plotline about domestic violence and the terrible dynamics in abusive households. The abuser is an alcoholic. He’s remorseful. You are given choices that show forgiveness or zero mercy. And everything you choose has a consequence. And the game is, thankfully, not trying to nudge you in the direction of forgiving the abuser at all (which given the dudebro-ness of the game surprised me). It brought up a lot of emotions for me and was in the end satisfying, even though the ending I had was by no means “happy.”

I’ve played all the bioware games with morality orientations which I enjoy, but are rather simplistic (you can see your morality on the screen as a red or blue bar). The thing I am appreciating about the Witcher is that every choice has a consequence but the choices are ambiguous at best.

My missus thought I’d like Witcher, given my love of Dragonage, but all the things you have mentioned are why I hate it. Even the amazing soundtrack can’t save it for me. Thief the same, I just can’t bear it, within the first mission I was like Nope! Gross.

If there is a choice between playing good or bad, I cannot play bad. Sure, in games like GTA that rely on criminality to further the plot, I’ll do that. And yes, of course I drowned/starved/set on fire some Sims. But as soon as your actions have storyworld consequences, I can’t bring myself to take the evil road. And to be honest, I’m fine with that.

Okay, so Undertale is awesome, and I want to talk about A Thing You Said in the article that someone hit on a bit in an earlier comment. Undertale is just an incredibly awesome experience, I just wanted to say that. It’s one of the best games I’ve played in terms of morality because it doesn’t give the player a “good” or “bad” option, it just gives the player the ability make choices (mostly choices about killing other characters) and then has consequences for those choices. I think that’s a much cooler, more realistic way to portray moral decisions.

SPOILERS SPOILERS SPOILERS SPOILERS SPOILERS SPOILERS BEYOND THIS POINT HERE BE SPOILERS

——–SPOILERS———

——–SPOILERS———

——–SERIOUS, END-OF-GAME, SPOILERS——–

——–SPOILERS———

You mention how the game takes on the assumptions the player makes about gameplay and what video games are like, and it does so with more than just getting rid of consequence-free killing in games.

You say, “With the genderless protagonist, the protagonist named after the player, the game puts the player in its world.” and I think that this means that you’re not finished playing the game because the protagonist actually isn’t named after the character. You, the player, get to choose a name which characters will refer to the protagonist as and you, the player, assume that this means that you essentially are the character in the game (it does immerse you in the game), but you’re not. At certain points near the end of the game it’s made clear that you may control this character but you, as a player who steps into this game with the huge power of being able to save and go back, are separate from this character.

In the True Pacifist ending it is revealed that the main character’s name is actually “Frisk” and what the other characters refer to Frisk as, the name you picked out, is really the name of the first human child to drop into the underground (as far as I could tell with the dialogue and plot in the Pacifist run I did the name I picked was actually the name of Chara, which if you’ve played the game has really interesting implications of it’s own). Frisk is a character who lives in this universe, and is thus distinct from you. This distinction is cemented when the fucking flower guilt-trips you whenever you open up the game after completing the true pacifist ending, telling you as the player, “There’s nothing left to worry about.” except for “One being with the power to destroy EVERYTHING … I’m talking about YOU.”and asks you to leave all of them, including Frisk, alone. This speech messed with me (I did not reset the game) because it’s one more part of the game that emphasizes how much power you have as a player, and that challenges your assumptions that you have the right and privilege to dictate the happiness of these characters.

Actually many parts of Undertale are great because they question why you, as the player, should have the right to determine the universe of this game even as it gives you the power to through gameplay.

So basically the game even screws up your basic assumption that you are the main character. Also, this means that the gender neutral character is actually, honestly gender neutral and goes by they/them pronouns. So, Undertale is the only game I know of with an openly, canonically nonbinary human protagonist. Which is really awesome.

——–End of Spoilers and comment———

Undertale has several nonbinary characters, and I love them all so much. Even that one.

Alright, especially that one.

Undertale is such a creative and clever little game! It’s also worth noting that some of the soundtrack was done by a trans woman friend of mine. She did all that wicked guitar work you hear in the main theme and in a couple of other bits throughout the game.

Ali I know nothing about gaming and will probably play nothing more than super smash bros for the rest of my life, but I love reading your gaming pieces!! Also very seriously considering looking at this game, if not actually playing it because puh-leeeeease let me find a way to connect boring medieval theatre to real life (cause you’re so right, those morality plays are not very good). Thanks for this!!

Yes! Undertale was fantastic. One moment dorky humor and bad puns and dog jokes, the next moment giving you complete agency in your choices and forcing you to live with it.

In terms of other morality games: I recently played Firewatch and I have a LOT of feels about it. No spoilers: It puts you in the role of a dude faced with tough life things, and obliges you to make tough moral choices as him. But it doesn’t offer you “heroic noble choice” vs. “scummy choice”: almost all of the choices are “morally sketchy choice” vs. “probably also a bad choice” (but all in very realistic ways). The protagonist is not a great person, and you have to make the choices that define it.

It was a very enjoyable, unsettling game to play, and you begin to feel… emotionally complicit (which I had never experienced to this degree from a game before). The gameplay is almost entirely just walking around in forests (which is fantastic), but the heart of the game is just… having to live with your character’s choices, and deciding whether to try to be emotionally open and trusting.

Would love to hear anyone else’s thoughts on Firewatch. because SO MUCH PROCESSING