There is a sense of community that comes with being a person of color, but for some of us, settling into that community isn’t always comfortable. Because we don’t get a membership card along with our birth certificate, finding our identity comes with the burden of having to “prove” yourself. Whether you’re bi-racial, adopted, or otherwise ethnically ambiguous, there will always be that person who wants to know, needs to know: “What are you?” And while most of us have a stock answer, secretly we’re thinking “I’ve got no clue, dude.” Many of us struggle to prove our authenticity to ourselves first, and find ourselves deeply attached to little reminders of our roots. And those reminders, large or small, become the thread that weaves the stories of our lives. These are a few of those stories.

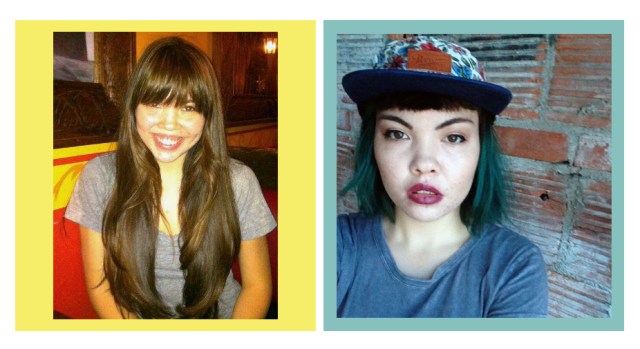

Hannah Hodson

I have always gravitated towards “alternative lifestyle” looks. When I got my septum pierced I was worried people might confuse me for one of “those queers” (It seems my fashion choices have always preceded my self-discoveries). One thing I have always wanted is to dye my hair a whacky color or get it all chopped off into a funky ‘do. As I’ve embraced my bisexuality that urge has only grown stronger. But there’s a part of me that has feels a longer standing allegiance to being a biracial woman. In particular, I’ve always felt like I need something to prove to others and myself that I am authentically African-American. Somehow, even as I remind myself that authenticity is an unattainable social construct, I yearn for a cultural heritage that I might recognize in myself when I look in the mirror.

Once, when I had lice as a kid, my father took me into the backyard and buzzed all of my hair off. He was very satisfied with his handiwork. My father, a white guy, had always been my hairdresser. My Black mother had her hair relaxed since she was a child and in fact the texture of my hair was more similar to the white boy ‘fro my father had rocked in his teenage years (before he went bald, that is) than hers. My hair was his domain. This meant that when I got lice it was also his job to slather my head in margarine and a swim cap before bed, boil all of my hairbrushes and discard my scrunchies. After my third infestation, he thought he would just save himself some trouble and just get rid of my hair alltogether. I don’t remember having a problem with it.

Upon returning home my mother was devastated that he would “mutilate” me like that. My Jamaican pre-school teacher and nanny told him that he had cut all of my “power” off. While pretty much nobody asked me how I felt about it, these two women were concerned for two very different reasons. My mother had internalized her idea of what good hair looks like: mine. And while she was content to douse her hair in chemicals every month, she saw potential for me. Her hard work and education afforded my sister and I opportunities that she had to fight for. Our fair complexions and loose curls would further help us live privileged lives. Maybe she was jealous? I mean she was also angry because it’s ridiculous that my dad thought it would be okay to shave my head without consulting her, but I think she saw in me the image of perfection, and he took that away from her. My nanny, on the other hand, saw my hair as my “power”: my Blackness. I think that stuck with me. Not only has my “good hair” been a marker of the many privileges I enjoy as a half-white person, but a way to remind myself that I am genetically, authentically, Black as well. One does not dilute the other.

And so, I rock my natural hair long and wild. I spend exorbitant amounts of money on paraben and silicone free hair products so that I can grow it longer and wider. I hang onto my curls like they are the very things that define me. I think it’s difficult to find a sense of balance when you are constantly being told you’re “not really black” or “not really gay.” Even as I consciously tackle these issues I feel like my hair is my security blanket, my constant. And it is precious. And you may not touch it because it is a mystery to you and that is okay with me. I’d prefer to remain mysterious while I figure my own shit out.

Carmen Rios

When I was a little girl, I notoriously insisted to my mother that one of her childhood photos was a photo of me. “C’mon, mom, seriously. When did you take this photo of me?” My mom is white, Italian, Bronx-bred and Jersey-raised. I am my mother’s duplicate, a tiny reminder of herself. I was raised by my mother and my mother alone, and in every way I am my mother’s daughter.

Except for the hair.

When I was younger, back before elementary school, I had long, soft, simple hair that fell in place and got put up in bows and buns and big hair clips all the time. I loved my hair. And then, when I got older, it changed. It tangled almost instantly, grew at the speed of light, and had more volume than any other head of hair in all of my majority-white, suburban classrooms. I was different. I didn’t know why. I fucking hated it.

I have my father’s hair. My hair stylist as a kid told me the texture was “hexagonal,” something she’d never seen before or really studied. By the time I graduated high school, I had attempted to straighten my hair dozens of times. None of the chemicals worked, except one, made up of various chemical compounds that were applied once a year in a six-hour non-stop marathon of hair care. My stylist used to close her shop down and have us show up on a Saturday morning, bagels in hand and magazines at the ready.

Someone told me once that my Puerto Rican roots didn’t matter because my father wasn’t in my life. “It’s not like you’re even really Puerto Rican.” It all came back in that instant like a flood. I remembered kids teasing me about my hair all throughout my childhood and late adolescence. I remembered crying in the mirror and in the bathroom and on my mother’s bed as we tried process after process to make me “normal,” “beautiful,” white. I remembered the day I cut my hair into an afro, and all the days after that where people verbally accosted me for it, interrogated me for it, judged me for it, made fun of me for it. (And I will most certainly never forget the people who pronounced it Car-Man Rye-Ohs, because that shit ain’t right.)

There’s this photo of my father that I saw once when I was in his brother’s home, and he’s graduating, and he’s young, and he has an afro. It was years before I would cut my own, but when I eventually did I would think about it and assure my mom I knew exactly what I was doing. “I have dad’s hair. I know what it’s gonna look like. I know it’s gonna work.” Sure enough, it rose at the roots and never fell down and stayed all the way up there for years.

My father’s hair watched me graduate college without my cap on, watched me buy the leather jacket and boots and go to my first lesbian bar, helped me kiss a girl for the first time. That hair taught me lessons and how to love myself and how to shine and be vibrant and be brave and be real. That hair taught me how to fight. That hair taught me to be weird and different and outrageous and authentic. And in a world where it can be easy for me to feel invisible and forget my own name, it still reminds me who I am.

Intern Cecelia

I remember the day I decided I was going to be really, super white. It was the summer of fifth grade and I filled journals with scribbled hate manga to spite all the Carly’s, Zoe’s and Taylor’s of elementary school. Then, I opened a new journal, this time filling it with hundreds of cut-and-paste pictures of beautiful girls in magazines. I didn’t know it then, but the privilege of being white passing means having the ability to choose how I’m viewed by others. Because regardless of my cultural background, racially I am pretty damn close to white on the spectrum from brown to white. Being authentically white was as close within my reach as some hair dye and a pair of tweezers, and because of that, I was obsessed with proving I could pass.

Unfortunately, when you’re eleven and sick of being bullied and having only internet friends, you don’t really see the “caution, permanently internalizing white heteronormative ideals” signs posted ten years ahead in the future. I didn’t realize that I was socialized to define success as inherently linked to whiteness, so I feverishly collected trophies (being adopted into rich white boyfriend’s family, becoming the bully) to nurse the hope that no one would notice I didn’t belong, because it always felt like I was almost there.

In reality, I’ve always been a Japanese and Jewish southern queer kid raised by a single mother from a lower-middle class background. These are the markers of my identity that, for years, never fit neatly into my plan. I’m unraveling the feeling that I should be ashamed of these things one at a time. A little over a year ago I started chiseling back the layers of my identity to find the queer underneath, eight months ago I actually started calling myself queer, and a few weeks ago I had one of those transcendent moments of self-actualization where my body clicked into the word queer without feeling hesitation or fear.

Truly accepting myself means letting go of the security that comes from trying to fit into convenient categories. I’m not sure what I am these days, but at least I’m not worried about what I’m supposed to be. Being a mixed race queer has taught me that there’s probably no way I could ever truly be what I’m supposed to be, anyway. After years of buying into an identity pitted against my own personal love and acceptance, it’s nice to finally live in the question of myself. Accepting ambiguity feels like being welcomed home.

Alley Hector

I often like to start my family story with names. See, my name is Alley Hector. I made an Iranian friend in Turkey once whose name was Ali and he said, “Hey our names are the same. But that’s a man’s name.” It wasn’t the first time I had been called Mr. Ali Hector in correspondence. My surname, my family name, too, is a “man’s name.” It also sounds vaguely Latino. Indeed, I am vaguely Latina. But not because of this name. This name, my family name, is completely made up.

The man who bore the last name “Hector” was semi-well-meaning dude, now a year dead, who married my single grandmother in 1964 when my mother was 14. He adopted her and my aunt, two girl-children with different fathers, born out of wedlock in 1950’s north Jersey. It was a pretty grand gesture so perhaps he deserved to attach his name to ours forevermore. Funny thing was, his father had actually completely made it up when he emigrated from Germany to sound more American. My mother’s biological father’s surname was Janin, though she had originally gone by Dennis, my grandmother’s maiden name, because that guy didn’t want to leave his surname behind. Which brings me to my father, who most likely didn’t want to leave his either, which is why I am not Alley González. But okay — this is supposed to be about being mixed race, not personal family drama. Unfortunately, for me, one cannot be teased out from the other.

Luis E González was from Caracas, Venezuela, schooling in NY/NJ in training for an engineering job with a prominent oil company. Though I’ve never seen him, my mother describes him as a short, thin man with olive skin and dark hair. Now Mom is a white mutt from the Tri-State area and I am too. My skin and hair are darker than hers but I still walk this country like the privileged white person I am. But there’s still that dark skinned guy, just sitting there uncomfortably in the background of my family tree, with no names lined up behind him.

In elementary school I’d often sign my homework Allison González-Hector and I was always trying to take Spanish lessons or do country reports on Venezuela. I even brought a mildly alcoholic drink to school during presentations one day, a coming-of-age drink you imbibe on your 15th birthday called Ponche crema. And I really did think then I’d have a Quinceañera some day. But by the time I actually was a teenager I wasn’t quite as ready to celebrate this culture I really only knew secondhand, this ethnicity of a man who had walked out and never looked back.

Now it feels disingenuine either way.

I was raised in whiteness and I walk through this world as white. I strive to be an ally to my QPOC siblings and seldom claim a space among them. But is disavowing my lineage just as harmful as pretending I have a knowledge of life as a QPOC that I do not? And here’s where family drama, cultural context, the larger institutions of racism, and immigration policies get all muddled. Now, where is that immigrant who moved from Caracas to get a degree in the states to help me when I need him? (I mean, I have all these questions, Dad, about who I am and where I come from, what languages I should speak and what my place is as an American.)

Actually, it turns he’s in Texas, and on LinkdIn. I found him there about 6 months ago based on his former employer. So I contacted him (you know, just to let him know I had a few questions about life and race and family).

But I’m still waiting to hear back.

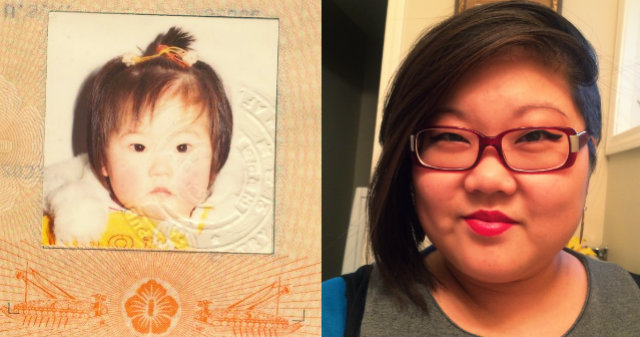

KaeLyn Rich

I was one of the smart kids in high school, an A-student, with a whole pod of straight-laced friends who didn’t drink or cut class. Like so many young closeted queer-mos, I have always been attracted to the extremes. Something about your feelings and desires and longings frantically trying to claw their way out through your arteries makes us want these things, amplifies the wanting: piercings, wild hair, getting too drunk on cheap beer and red wine, tattoos, skirt-hikes in dirty bar bathrooms, getting the boi or girl in the leather jacket, being the boi or girl in the leather jacket. Whether that was about being the only Korean in my school or about being in the closet or neither or both, the feeling was overwhelming. I can still feel the places in my body scorched by that wanting, that deep frenetic desire.

Somewhere around my senior year of high school, I started to quietly lash out. I kept up my grades, but started wearing funkier clothes and makeup, dyed purple streaks in my hair, went out with older bad boys from other schools, snuck into bars with a chalked ID, and fumbled my way into my sexuality. When I went to college, I picked a school where I’d be the only one from my high school class. The night I arrived on campus, I went to a frat party and made out with girls. By the end of the first weekend, I had pierced my tongue. And before thanksgiving break, I had my first tattoo.

I knew my first tattoo would be my Korean last name, the name I was assigned before I was adopted. My Korean name was probably not my first birth name, as my “origin story” is one of those adoptee story cliches and was probably meant to cover a less sweet story. (On my adoption paperwork, I am a “foundling,” meaning no one surrendered me or took me from my first home. I was “found.”) My name on my adoption paperwork is Lee Eun Jeong. I can’t pronounce it correctly because I don’t know Korean. I do know the the “l” in “Lee” is pronounced like a “y” sound in Korean.

I know this because the white guy who did my tattoo of my Korean name was stationed in Korea for four years. When I walked into his shop, he said my laugh sounded Korean. My laugh is different or, uh, distinctive, you might say, but I’d never thought of it as possibly being tied to my ethnicity. Until I finally embraced being Korean, which really only happened a few years ago, I always felt like an imposter, that I was white by nature of the passing privilege handed down by having white parents. That bits of my Korean-ness were showing anyway, despite my best attempts at hiding them, was both unsettling and fantastic. I had him do my name tattoo and two others after that.

My name is KaeLyn Rich, my legal name, the name my parents gave me when they adopted me, the only name I know and answer to, the name I can pronounce. My first name was Lee Eun Jeong, assigned by the orphanage, strange on my tongue. My last name is my Dad’s Italian family name, changed from Ricigliano at Ellis Island. My mother’s family names are Swedish and German. I am part of my family’s legacy, but the legacy behind my family names is not mine, not really. I will never resemble any great aunt or have kids who look like my father’s brother. My people didn’t live in these countries, eat these foods, wear these clothes. My family is my family, held tight by loving and legal bonds. My family names, however, do not correspond to the nameless baby girl “found;” to the girl with the generic Korean name adopted; or to me, now, the American woman with the pseudo-Gaelic first name. KaeLyn is the name I know, the best version of me, the familiar and the strong and the passing and the comfortable. The foreign name permanently inked on my spine in black and red, I will always be reaching back to.

Comments

Right in the heart <3

Thank you all of you for writing about your experience. I’ve been having a delightful racial existential crisis ever since I got side-eye in high school for winning a ‘National Hispanic Scholar” award. Like Alley, I’m ‘vaguely latina’ except that I was raised within the chican@ culture. Even though I was raised in the culture, my skin color (which is a stark contrast the dark indio skin of my extended family), anglo last name, and mild spanish fluency negates all of that.

My current struggle is if I am a “person of color”. If I’m related to people of color, does that make me of color? My current inclination is “no” because I’m very fair skinned and get red as white or Spanish. But if I don’t identify as a QPOC, am I turning my back on my people?

*read as white

I’m having a pretty similar issue, I think, and though I can’t give you an actual answer (thanks for replying then, Gabe!) I thought it might be helpful to share my thought process and my feelings on it, as awkwardly expressed and circular as said feelings are. My father and his family are Arab, see, but I’m the whitest person in the world and my Arabic is limited to the basics – and a few niche phrases for the benefit of distant relations or non-family, like ‘Yes, really’, and ‘No, my father is Lebanese’, and explanations of where exactly Wales is anyway, and recently ‘Yes, I did mean ‘she’.

When my involvement with Middle Eastern culture is pretty much just limited to Dad’s cooking and the occasional big family gathering – where almost everyone has a different first language anyway, from Welsh on my mother’s side to a variety of Arabic dialects and African languages on my dad’s, so we tend to all just speak French or English – it’s hard to know where the line is. Is identifying as a white-passing Arab the ethnic/cultural equivalent of a kid dressing up in Daddy’s clothes? Is it, given my overall whiteness, just plain appropriative? But although I wasn’t raised in Arab culture, the glimpses I get of it and my own occasional frustrated attempts to learn about it are very important to me – is identifying as white denying that part of my background?

I think what’s most accurate is to identify as white, since for all intents and purposes I might as well be. There are people who are uncomplicatedly white in background who know more about Arab culture than I do, and there are plenty of people who are uncomplicatedly white who are far less ‘white’ in appearance than I am. The term ‘person of colour’, though not necessarily the identity that goes with it, is – I think – tied up in negotiations of privilege systems, and regardless of my family’s background, I personally have as much white privilege as any ‘real’ white person. It seems disingenuous to claim otherwise – identifying as white seems the most honest response here (and the most literally accurate, given that I make snowmen look tan). I just really hope it doesn’t mean I’m rejecting anything I want to keep.

My dad’s side is made up of very very white mexicans, some of my family embraces the hispanic label enthusiastically and some still live in Mexico. But, my dad never learned spanish and has always used “white”. I used to use the label “white” but, in my state, when filling out those lovely demographic bubbles it says “white (non-hispanic)”…which makes me feel like I’m slapping my grandmother in the face. So, now I use “hispanic,” with a side of guilt and weird “one-drop” feelings.

“But if I don’t identify as a QPOC, am I turning my back on my people?”

This, so much this

Hey everyone, so sorry I am just replying now because I hadn’t realized this had gotten published yet. But firstly, thank you all for your support and solidarity.

I too (clearly) don’t have the answers but I think what I’ve read here so far rings true. What I try to do as best I can is acknowledge my heritage but also my privilege and what that often means in practice is supporting QPOC projects but not actively taking up space. Like I almost didn’t even contribute to this but then realized it was important to tell my story if only in this particular roundtable. Otherwise I generally don’t speak up as a person of color and acknowledge the much more difficult issues those of color have to face.

This, oh my gosh.

My mother and her family came to the US illegally from Mexico when she was two or three. They were sent back twice. They lived in empty houses that they didn’t own, or in the dining rooms of their fellow immigrants while my grandfather looked for work.

My dad is a white guy from Philly who was raised in a broken home by a bigoted family. He asked my mother if she ever rode a donkey in Mexico, and threw up when he saw the various cow parts they’d be eating for dinner at her family’s ranch.

My mother taught my brother and I simple words in spanish when we were young. We call our grandfather Welo, because it was easier for us to say than Abuelo. We visit her family almost every summer and sit in silence while they talk around us, too scared to jump in with our first grade level spanish. Her family doesn’t know that I’m transgender, or about the handful of girls I thought I loved.

My brother would go outside with my grandfather and uncle and grill fajitas for dinner. I was jealous, on some level. I was stuck inside while my grandmother and aunt hemmed and hawed over how they should braid my thick curls and smacked me with the wooden brush if I moved.

My brother has always been the darker-skinned of the two of us. He looked so natural out there. He talked and laughed and grilled with them. He got to take part in their traditions and their masculinity.

My mother still makes me pack sundresses when we vist. I wear them over my binder and my extra-strength sunscreen.

Ya’ll are collectively kicking me right in the mixed girl guts. <3

So many feels! – my grandmother is an awesome Japanese woman but I look blindingly white and basically all I know re: Japan is how to count to 10 and eat sukiyaki. So I am not connected to that branch of my family tree at all.

A few weeks ago though I was at the Met in the Asian art section. There were a bunch of statues from Japan and I was like – OH MY GOD THAT’S MY FACE. People used to poke fun at me for my “squashed nose” and “baby cheeks” – I never thought maybe my round face was inherited instead of just quote-unquote plain. And then the other day I was in Sephora for the first time and they took my shade for foundation/concealer and were like, no wonder you can’t find anything that matches at the drugstore, you have the palest skin with olive undertones we’ve ever seen.

And sometimes I’ll be on the train and some douchey white guy will be talking with his friend and he’ll be like, Excuse me, what are you? And the only time I was naive enough to say, Um, my grandmother is from Japan, he punched his buddy in the shoulder and said, See, I told you she was Asian. Way to make me feel fetishized and objectified, jerk.

So yeah. All small things, but a lot of feels that make me want to be the best ally to POC I can be, since it’s clearly such a minefield to navigate a society built on norms of whiteness.

Carmen I can relate to the hair. As a kid(middle school and above) I too had kids judge my hair. In fact kids use to say it feel like a Persian rug. I wanted to cry when I heard it, but then years later it had me wondering is that really an insult since Persian rugs are finely woven and expensive? I’m still not sure if it is, but I do know what it’s like trying every chemical just to get my hair straightened and nothing ever working for more than a day.

I found myself relating to your stories. Though the vast majority of my ancestors were black (descended from slaves). My maternal line was unique in that I’m descended from the free black mistresses/courtesans common in New Orleans. I’m fairly sure I have distant cousins that passed at the end of civil war. My own family branch married dark skin men and we’ve done.

But we’ve always said there is no dishonor in passing. No one has the right to tell a multiracial person how to live. It’s your choice and life as a white person/with white has its advantages. If for no other reason white people seem to be a couple decades ahead on LGBT tolerance.

Oh man, I relate to so much of this. Even the hair – I try to get an Alternative Lifestyle Haircut and nobody reads me as queer, sigh.

It’s kinda frustrating for me that the only stories I can relate to are from adoptees and multiracial people, because I am neither of those things. I am pretty much a Third Culture Kid, though a lot of those stories tend to come from people with slightly more privilege than I do (though i do have quite a bit). But the constant “where are you from”, the “you’re not POC enough” (er, I’m Asian from Asia with dark skin, how much more POC do you want me to be – OH RIGHT it’s because my politics are subtly different because I had different experiences! Of course! ffs), the not knowing which culture to identify with because they all seem incomplete and fake.

Thanks for this.

“I didn’t realize that I was socialized to define success as inherently linked to whiteness”–

I may not be mixed raced, but this really resonated with me as an Asian kid in a predominantly white, European-Canadian area.

So happy and thankful seeing even more QPOC perspectives on AS.

Thank you thank you thank you!

I read and re-read this post and felt really connected. Like some of the other commenters I’m also Mexican, except that I was born in Mexico, grew up in Mexico until I was 9, then spent my formative years in Ithaca and Syracuse (hi @kaelynrich, I wish we’d met when I lived there, it would’ve been so nice to have one queer friend) and for the last seven years I lived in Mexico. Mexico is my everything and it’s completely in me, but I am a very light skinned, white Mexican. I’m mixed of Lebanese and French descent, and while I tan easily, I’m just white. I get confused for Italian, Turkish, Lebanese, and Pacific Islander sometimes, so maybe it’s a little questionable how white I look, or what accessory I am wearing that identifies me as one over the other. So when I was coming out as queer I desperately clung to my queer signifiers, piercings, thumb rings, ear expansions, alternative lifestyle hair, and chucks. Lol. When I was in college I had a really hard time because I was nearing the tail end of 13 years in NY, and felt disconnected from my roots. Also I was having gay girl feelings and felt like I didn’t have anyone to be like “I KNOW ME TOO!” about stuff and things re:queerlatina.

I just left my dearest Mexico again, forever, and I am so sad, but also so lucky to have found the kind of love I’m into and to marry in North Carolina. I feel it’s gonna be really important for me to make friendships here that are everything from this post! Can y’all move here and be my friend? K, thanks,

O, my beautiful autostraddle soulmates… You have no idea how this post has seriously sung to the smallest molecules of my being.

24yrs old, adopted from southern Chile as an infant to loving tall white parents and a Peruvian older brother. Many other friends adopted from L. America to older white parents; i love them for being a necessary mirror of my family’s portrait but our stories vary too much in circumstance, experience and self image to really compare.

I can really relate to the self definition that comes with ethnic and sexual ambiguity. “What are you?” Is more than just a question by strangers trying and failing to flirt- its what ive asked myself too oftern to mention.

Let me just say- right now i am in chile. I asserted myself into a study abroad program here. After my first week of walking i have seen in the people here my thick hair my plump cheeks my little belly my scar (from a vaccine given to all chilean children) my stumpy fingers- all of it. Its astounding. Meeting my biological mother and aunt next weekend- wish me luck.

Its crazy. Things have clicked here. I am comfortable. But also so so gringa. All my life people ask me in the US what am I- I say Chilean. Here they ask me the same question- i say “estadounidense”. So.

Very interesting though how queer life survives here. Especially outside of the big capital city of Santiago. I am as of yet smack dab in the middle of this thing called self discovery; wont have any conclusions until way after when i can digest all that happens here.

All i can say for now is that being self defined by race, ethnicity, gender expression or sexuality is perhaps a more difficult road to take, full of self doubt and uncertainty of belonging/membership, BUT! What a freedom it is. What a freedom what a freedom.

I totally understand where you are coming from in terms of answering the “What are you?” question. When I’m in Australia and people ask what am I, I say Arab. When in the Middle East and people ask what am I, I say Australian.

thanks for this!

Yes yes yes yes. More please.

A lot of this really resonated with this white Jewish queer in terms of trying to be ‘authentic’ or connected to my culture but feeling like an outsider. I always feel too much, too little and all the wrong things. So much of what you all wrote really touched that for me so thank you.

Oh. Thank you all so much for this. It all hit home more than I realized, especially this part from intern Cecelia: “I’m not sure what I am these days, but at least I’m not worried about what I’m supposed to be. Being a mixed race queer has taught me that there’s probably no way I could ever truly be what I’m supposed to be, anyway.”

That’s definitely it for me, too. While I was jokingly called “the white one” amongst my siblings growing up (I still don’t know exactly what that means), it doesn’t mean the black and Mexican parts of me aren’t valid. I’m also a self-identified queer kid, which only makes me check off more of those category boxes in life.

I guess what I’ve realized is that my identity is more than what I look like (or what people *think* I look like), but my mixed-race…ness is a huge part of it.

Thank you for this article. My mother is white and my father immigrated to the US from Cuba. Like many Cubans, his family/ancestors were a mixture of Chinese, Spanish, and African.

In school, I pick up Spanish grammar and syntax very easily, but my accent is terrible. I have blue eyes and light skin, but my facial features undeniably scream “not white.” Now, everything from Census forms to people on the street asking me “What are you?” confuse me and I don’t know how to answer.

I love to learn about Cuba and speak Spanish with my father. I’m trying to embrace my heritage, but it somehow feels wrong. When I’m around non-Latinx people, I feel like the Latina in the room. But when I’m around Latinx people, I feel like a fraud.

I just started thinking about all this last year, when a teacher pointed me out as an example of the “product of a mixed-race marriage.” I’m trying to stop thinking of myself as white or Latina and start thinking of myself as white and Latina.