To discuss feminist theory, you first need to be able to visualize a roadmap of what the fuck feminism is. For just like you and I contain multitudes, so does the movement which advocates for women’s empowerment and equality. Feminism itself is made up of lots of itty bitty (or super major) factions, although they aren’t necessarily at war; it’s also come a long way, and is still evolving. But don’t lose hope! It’s easy to get a handle on all of it with a birds-eye view.

First Things First: What The Fuck Is A Wave?

Women’s studies is no trip to the beach, but a casual conversation about the feminist movement might take you there. “She’s so first wave,” I’ve often remarked dismissively with my wrist limp. But what does that even mean? (Pro-Tip: It means you’re not relevant and need to stop pushing your outdated bullshit. But I digress.)

“Waves” are the way we divide up feminism’s generations. The visualization is apt, seeing as the ebb and flow of the movement has contributed to the radical differences between each instance of its actualization. Women have been fighting for their right to party just as they please and alongside anyone else for a long time now, but the tide has only come four times. (Or so they say.)

The First Wave (1800s – 1920)

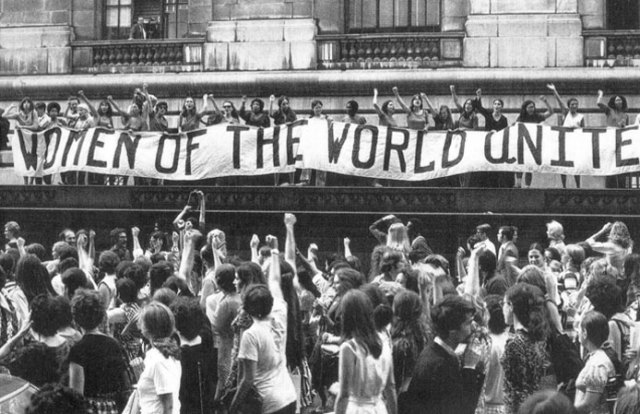

The first wave of feminism was the birth of the American women’s rights movement, though it also emerged parallel to similar movement across the world. Most first-wave feminists wouldn’t have called themselves feminists, and many came from existing activist backgrounds in both the temperance and abolition movements. First-wave feminism was primarily focused on women’s suffrage, which they won in 1920 with the passage of the 19th Amendment, following years of crazy-ass shit like hunger strikes and badass big-bannered protests outside the White House and inter-state parades on foot to galvanize support from men for their own enfranchisement.

Women like Lucretia Mott, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, Victoria Woodhull, Carrie Chapman Catt, Sojourner Truth, Lucy Stone, and Alice Paul defined this era in American women’s rights, although they all varied widely on their desired goals and approaches to relative gender equality. Some suffragists did not believe in a gradualist approach, and some did — thus birthing the first-ever in-fight of the official feminist movement when the National Woman Suffrage Association (who advocated for federal suffrage rights) and the American Woman Suffrage Association (which wanted to work on suffrage state-by-state) found themselves warring for a victory. Ultimately, the two groups would merge in NAWSA, the National American Women Suffrage Association, and Alice Paul would deliver them from relative evil into relative champagne-popping voting parties.

#FunFact: American women who fought for suffrage were called suffragists; women in the UK who did the same were called suffragettes.

The Second Wave (1960s-1980s)

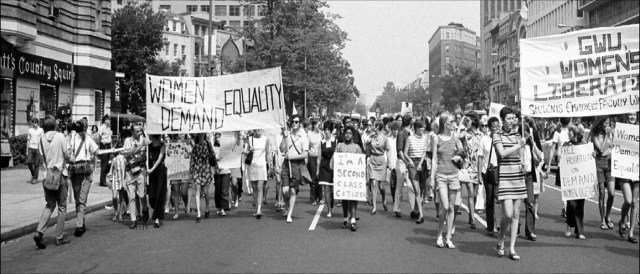

Feminism’s most notable wave is the second — colloquially, it refers to the period in the 60’s and 70’s in which feminism once more became an organized, cohesive effort for women’s equality. Following the baby boom and post-WWII return to traditional gender roles, women found themselves smack-dab in the middle of revolutionary times wanting more. First-wave feminism had brought women’s rights into the political sphere, but second-wave feminists would build on those victories with an insatiable desire for “de facto” equality, AKA both social and legal gender parity, albeit through political means. The second wave movement largely refers to the “women’s liberation” movement, in which women like Gloria Steinem and Betty Friedan challenged gendered notions of womanhood and the socialization which kept women in the kitchen. They would also popularize the term “feminist.”

In 1963, the movement actualized when Friedan published The Feminine Mystique, thus revealing that “the problem with no name” that plagued America’s housewives was (SURPRISE!) their limited access to achievement and individuality in American culture. Steinem, later that year, would publish two groundbreaking essays about her time as an undercover Playboy bunny, remarking on how sexism had impacted men’s understanding of and value for women. That same year (I know! What an awesome year!), John F. Kennedy’s brand-spankin’-new Commission on the Status of Women released their first-ever report on gender inequality. Eleanor Roosevelt, secretly queer powerhouse of the second wave and my utter and complete idol as a child, was the chair. By 1964, Friedan had begun to talk of “a movement.” In 1966, she founded the National Organization for Women and watched that movement actualize. (Her homophobia, which also produced The Lavender Menace, is no longer integral to NOW’s core mission.)

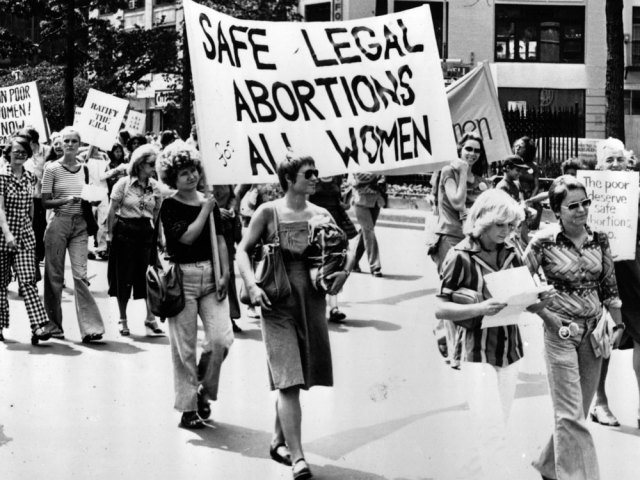

The second wave experienced an amazing batch of victories in their two decades: the Equal Pay Act of 1963, the Civil Rights Act of 1964, legal access to birth control and abortion via the Supreme Court in Griswold v. Connecticut and Roe v. Wade, Title IX and the Women’s Educational Equality Act, and the Pregnancy Discrimination Act among them. Believe it or not, many of these pieces of legislation and historic Court cases still mark the furthest we’ve ever come on issues like reproductive rights, workplace discrimination, and ending sexual assault.

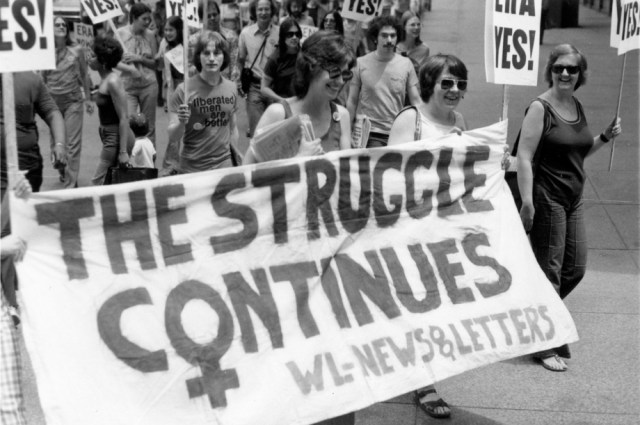

The second wave’s biggest goal, however, was never realized: the passage and ratification of Alice Paul’s Equal Rights Amendment to the US Constitution. (The worst part? It was defeated entirely by this awful woman named Phyllis Schafly.)

The second wave tapered off during the “feminist sex wars” of the 80s, in which a bunch of horrified and less horrified women debated whether or not dudes looking at porn was okay and what people should do about it. Believe it or not, this issue of their time literally divided what was an Earth-shaking force for women’s liberation. The movement, of course, still prevailed — in 1987, the Feminist Majority Foundation would be founded after a survey discovered that a majority of Americans (women and men!) identified as “feminists.”

#FunFact: very few bras were actually burned during this period of time, despite legions of legends to the contrary.

The Third Wave (1990s-Present)

The third wave of feminism arose out of both the failures of previous movements for women’s equality and a rising backlash against their victories.

With a focus on intersectionality, particularly with respects to queer women and women of color, the third wave defies essentialism, seeks to destroy all binaries, and goes beyond the second wave to advocate for an end not only to blatant sexism, but to stereotypes and representations of women which are harmful and impede their ability to be whole people. The third wave is multi-disciplininary, reeking of elements from girl power, riot grrrl, postmodern, transnational, post-colonial, cyberfeminist, ecofeminist, trans, queer, and racial politics and philosophies — among others — and is the first of the now-existent four waves to really embrace sex positivity as a principle.

#FunFact: There isn’t much to say about the third wave that you don’t already know, because we’re smack-dab in the middle of it. Or are we?

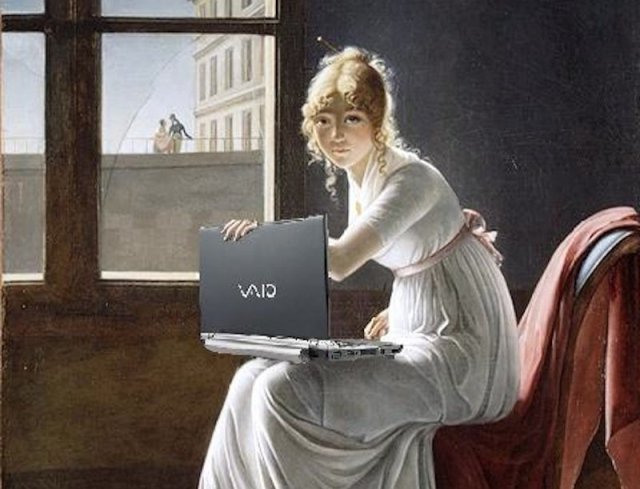

The Forth Wave (2010-Present)

In 2010, Shelby Knox published a post on her personal blog declaring herself not only a feminist blogger, but a founding mother — of the Forth Wave. Her conception of feminism’s newest incarnation was that it was one in which the Internet and a growing interconnectedness of movements had birthed an entirely different organizing structure and re-engaged young women in a movement which, to this day, people refuse to believe is still powerful and galvanized:

I’ve recently felt the pull of the blogosphere. As I become more outspoken in my feminism, I want to put my thoughts and ideas out there for the community to bounce off of, to critique, and expand upon. Most of all, I want to showcase what I see as I travel across the country: a vibrant network of young gender justice activists organizing in ways very specific to our generation.

I’m writing a book on this cohort, what I’m calling the ‘Forth Wave’ of feminism. Many of us in the Forth Wave found and continue to develop our feminism online. We use the internet to consciousness raise, plan rallies and fundraisers and readings, and collectively expand our movement.

Breaking It All Down: Different Feminisms

Not everyone has always agreed on how best to achieve feminist victories, nor have folks always agreed on what that looks like. This is compounded by the fact that many feminist movements have been actively exclusionary — for instance, when activists within the suffrage movement were willing to court racists for support and prioritized the voting rights of white women over black Americans — and thereby drove the invention of new, more inclusive movements. Some folks believe in capitalism, others in communism, and others in nothing at all. Some feminist theorists are real deep into breaking down the binaries and structures we use to define our existences, and others are fixated on building up the perceived feminine. We all care about an end to oppression and equality for everyone – but you’d be surprised how different we can be.

Anarcha-Feminism

What’s It About? This one’s pretty straightforward: if you smash anarchism and feminism together, you get Anarcha-Feminism. (If you smash the state in the process, you get bonus points.) A belief that women’s equality hinges on the liberation of all people from systems of hierarchy is essential here, as is a belief that in order to fully destroy hierarchy we must also destroy sexism. This sect of feminism is also credited with having invented the “manarchist,” though you shouldn’t hold it against them.

Who Knows All? Emma Goldman, Germaine Greer, and that dumpster-diving chick you knew in college who really hated authority.

Cultural / Difference Feminism

What’s It About? Cultural Feminism emphasizes the difference between men and women — but also holds strong to the notion that gender is a psychological and social construct. An essentialist view of a “female essence” propels these theories, which often seek to validate and honor typically feminine qualities. Cultural feminism faces critique for its limited view of gender, as well as its underlying focus on personality and lifestyle rather than legal and political equality.

Who Knows All? Margaret Fuller, Brooke Williams, and your friend who sometimes seems to not get feminism at all.

Exclusionary / Separatist Feminism

What’s It About? Separatist Feminism straight-up isn’t down with dudes. Exclusionary feminists — who may identify as straight or queer — believe that men cannot make positive contributions to the movement, and that women’s full equality is discovered in isolation from them and the culture they’ve created. Different-sex relationships are seen by separatists as being inherently imbalanced, unequal, and antifeminist. Be it through celibacy or lesbianism, separatists often practiced what they preach — and still do — by living away from men or in isolation only with women and girls.

Who Knows All? Mary Daly, Charlotte Bunch, Elana Dykewomon, Cell 16, the misandrists on this website.

Individualist Feminism

What’s It About? Individualist Feminism is another term for Libertarian Feminism, which, if you’ve stopped envisioning fedoras by now and are ready to learn, is based in the core belief that women’s equality comes from “freedom of coercive interference.” Individualist feminists focus on self-reliance and minimal government interaction with women’s lives, as well as full legal equality that is uninhibited by gender or class, and sought to find general and individual solutions to everyday and institutional sexism.

Who Knows All? Joan Kennedy Taylor, Suzanne La Follette, maybe Ayn Rand.

Liberal Feminism

What’s It About? Liberal feminism is the most mainstream of all the feminisms in America, and advocates for achieving gender equality within the current systems of America’s institutions — namely, politics. Liberal feminists advocate around issues like reproductive rights, equal pay, an end to sexual violence and harassment, voting rights, and access to education. (Sound familiar? Sounds like my day job.) Liberal feminism relies on women taking action to achieve change politically and legally.

Who Knows All? Gloria Steinem, Rebecca Walker, Ellie Smeal, Shelby Knox, Carmen Rios.

Material, Marxist, & Socialist Feminism

What’s It About? Material, Marxist, and Socialist Feminism all have one thing in common: they see unequal labor structures and capitalism as key oppressors of women and contributors to patriarchy. Marx felt his revolution would destroy not only class, but also gender; other feminists in this category feel that women need to join with all other groups in demanding an end to class hierarchy, thus eliminating gender difference as well. This vein of feminism has been criticized for placing the class struggle above gender equality in their work.

Who Knows All? Christine Delphy, Dolores Hayden.

Multiracial / Women of Color Feminism

What’s It About? Multiracial Feminism emerged parallel to the white women’s liberation movement in the second wave, although women of color and their collaborations with white feminist groups were often overlooked. Multiracial feminists organized alongside white women, in groups of women of color, and also in smaller groups divided specifically by race. The movement united, then, Chicana, Native American, Asian American, and Black feminists in America during the second wave — and pushed not only men, but women to see sexism as just one example of a structure of dominance and to destroy all of the rest.

Who Knows All? Dr. Maxine Baca Zinn, Dr. Bonnie Thornton Dill.

Indigenous Feminism

What’s It About? Indigenous feminism believes that the modern feminist movement in America was co-opted from Native women by white women, as part of the system of colonization. Indigenous feminism fights colonial ideology and argues for the large-scale adoption of Native forms of governance and community values to bring and end to patriarchy, oppression, and hierarchy, as explained by Andrea Smith.

Who Knows All? Andrea Smith, Jessica Yee, Eileen Morton-Robinson

Chicana Feminism/Xicanisma

What’s it about? Chicana feminism holds that not only are Chicana women exploited, but that Chicano culture as a whole has been politically and economically exploited by Anglo culture in harmful ways. It also addresses the ways in which women may be oppressed within Chicano culture. Chicana feminism can be roughly dated to the 1970s; the Comisión Femenil Mexicana Nacional was held in 1973. It focuses on the ways in which the experiences of Latina women are different than those of other women, and prioritizes their political, economic and social status.

Who Knows All? Cherríe Moraga, Gloria Anzaldúa, Ana Castillo, Norma Alarcón, Mirta Vidal

Postmodern Feminism

What’s It About? Postmodern feminism is all about blowing your mind. By refusing to accept gender or sex as “inherently” anything, postmodern feminists have pushed forward in urging society at-large to view gender, sex, and other binaries and assumptions as performative and undefinable, and thus nonexistent. If there is no hard categorization for gender and sex, there is thus no single reason for the oppression of those seen as women — which forces all of us to dig deeper about the engrained beliefs and behaviors that guide our understanding of the world.

Who Knows All? Judith Butler, Donna Haraway, Mary Joe Frug, Michel Foucault.

Radical Feminism

What’s It About? Radical Feminism identifies the core of women’s oppression as male dominance in a capitalist society, and thus seeks to completely uproot traditionally patriarchal systems of power to fix their inherent and gendered imbalances. Radical feminism is also now one of the last vestiges of trans-exclusionary feminism, which Annika trashed gloriously on this very website once, and also was the starting point for various forms of exclusionary and cultural feminisms.

Who Knows All? TERFs and other radfems trolling your Internet every day.

Standpoint Feminism

What’s It About? All women live at different intersections of oppression, and thus there can be no universal “condition” of woman. This is the main viewpoint of Standpoint Feminism, which encourages women to examine the intersections they’re living at every day and how those impact their experiences related to gender and sex.

Who Knows All? Dorothy Smith, Nancy Hartsock.

Transfeminism

What’s It About? When trans women first began to assert their inherent belonging in the women’s movement, they called their branch of feminism “transfeminism.” Although many trans scholars and activists now prefer to join the larger coalition of the women’s movement, the term specifically refers to feminisms that encompasses not only trans individuals, but the issues they face. Moreso, it combined feminist scholarship and theory with trans and queer theories, thus bridging the gap between the two worlds.

Who Knows All? Kate Bornstein, Julia Serano, Sandy Stone.

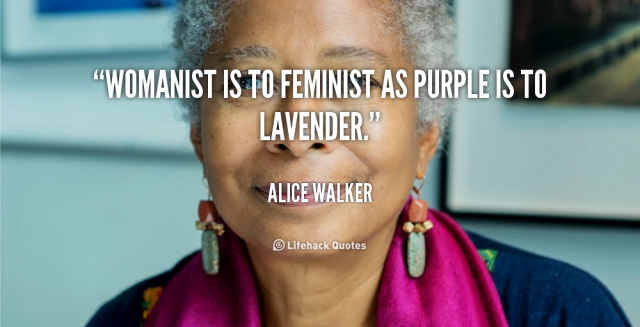

Womanism / Black Feminism

What’s It About? Womanism was born of a void in the feminist movement. Whereas white and middle-class women had achieved great gains under the umbrella of “women’s equality,” women of color — and black women in particular — had been excluded or struggled to benefit from the same victories. Thus, black feminist activists came together to work on issues of black feminism, and worked with a perspective that race, class, and gender were inextricably linked – and that oppression based on any had to go. By calling out the racism of the mainstream women’s movement and also working toward more inclusive gains, groups like the Combahee River Collective and individual activists alike inadvertently created a more balanced and intersectional approach to women’s liberations. Alice Walker called this particular strain of feminist thought “womanism.”

Who Knows All? Alice Walker, Angela Davis, bell hooks, Kimberle Crenshaw, Barbara Smith, Florynce Kennedy.

Rebel Girls is a column about gender and feminist theory and the founding mothers of the women’s movement. It’s like a women’s studies class, but better! Mostly because nobody has to wear pants.