Idol Worship is a biweekly devotional to whoever the fuck I’m into. This is a no-holds-barred lovefest for my favorite celebrities, rebels and biker chicks; women qualify for this column simply by changing my life and/or moving me deeply. This week, I’m interviewing one of my only real-life feminist heroes: Melissa Gira Grant.

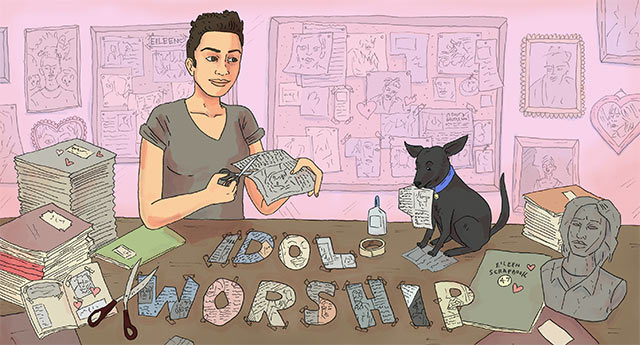

Header by Rory Midhani

Melissa Gira Grant was one of the first women who showed me what feminism looked like, and what it really meant. And almost half a decade later, I’m still relying on her definition.

I wrote an MGG appreciation post on Autostraddle last year but that was barely a sentence’s worth of her genius and her person in those words. And I’m back here because I think she’s more.

I met Melissa working on THE LINE, and even though it was my first internship and the two women (MGG and my forever mentor / feminist goddess Nancy Schwartzman) I was working with turned me into a firecracker, I came on board with a lot to learn. Until that point, feminism was just a concept to me — a set of definitions, not lived experiences, and a theory worth studying rather than a philosophy you could live. Looking back, I’m glad that internship was my first foray into feminism, because it was perfect: working in sunny apartments, eating Chinese food together at small desks in a rented office space, telling stories and working on three silver Macbooks. It was a space where I grew and I really became: I learned exactly what I could do and what I loved to do, I learned to always send emails signed simply “xo,” and I learned what I believed in and what feminism meant to me. Melissa, a queer writer and activist who loves the Internet, was thus one of the two most important teachers I’d ever had. (Very obvious now, but hindsight is 20/20 and back then I didn’t know I would sell out to a set of wires by 23.)

MGG, at the time, had long blonde hair and drank a lot of iced coffee. Our conversation topics included, but were not limited to: boys, my family, college, sex, bisexuality, being and/or not being goth (take one guess), and New York City. Melissa taught me what feminism was through her very existence: she lived her own beliefs, and so easily could pull them up in conversation that I wondered if maybe I should get some of my own. She challenged me on queerness, on sex work, on intersectionality, and on my own lamestream feminist beliefs that had been imparted on me by a biased media and a broken movement. I had so much to learn from her, and I still do, and I wanted to learn it then and I still want to learn it now. Melissa had, and still has, no keeper, no authority, no ceilings.; she carved out a life for herself in which she was pursuing what she loved, and she wasn’t ashamed or embarrassed about her past or anything she’d done. She was proud and therefore defiant, stood tall even among giants. We talked shit about mainstream feminism together in little nooks and she made me realize that the nuances feminists were often fighting about were more than principles and concepts: they were lived experiences.

Melissa, a former sex worker and active part of the movement for sex workers’ rights, doesn’t stray from the truth when she writes or when she organizes. I watched her once come to a launch party for a project I’d worked on and tell the founder, right on the side of the dance floor, that her language and strategy was isolating to queer people. She called out people she respected and worked with, and people who were making waves in the feminist movement, for refusing to accept the rights and agency of sex workers as intrinsic to the movement. She spoke loudly about what she believed in and remains an unwavering advocate for people living at the intersections of oppression, unwilling to quiet down even for her own sake. Melissa taught me that to love the movement, you have to try to change it.

When I bought MGG’s anthology Coming & Crying, I couldn’t afford the nicest Kickstarter package but my book still arrived with a note: “excited to publish your stories one day.” I laughed out loud when I read it because I was 20 and it was a book about sex and I couldn’t imagine ever being the kind of person who would write something Melissa would read. But I was wrong. I’d started my journey into anti-rape and sex-positive activism an innocent young thing, and MGG helped raise me into something much more remarkable and brave. Now, I share my stories with people every day when I have the chance; I put into words exactly where I am and how it’s impacted my world. I speak from the heart. I don’t tremble when I shout.

I read Melissa’s work — on the web, in books, in magazines — because it makes me smarter and more nuanced and more empathetic. I become more convinced. I begin to know myself a little more each time. Her career confused me when we first met: she completed a mix of regular 9-to-5 work at Third Wave alongside freelance work and writing, and I’d been raised with the ideal of graduating into an office space and living there for the rest of my life. It’s clear now how seeing women like Melissa who pursued projects and careers that they loved impacted my own participation in the movement. And it’s partially because MGG taught me about speaking truth to power, doing what I believe in for a living, and not being afraid to tell my stories that I became Carmen Rios.

When C&C arrived at my house on Arizona Ave, Brandon was in the room and I told him, “Melissa’s going on this book tour and I hope she comes to DC because oh my god, she’s just living feminism in this way. I just want to know more about her. I just want to learn more.”

“Tell her to stay here,” he said. “I wanna meet her too.” Melissa is so endlessly interesting and unique that it doesn’t take much to wish she was someone you could ask questions of or get advice from or sit across from at a restaurant.

In the years that passed since, I cut my hair and came out and still I met up with MGG a few times but mostly peripherally, and still each time I’m in New York City I’ve shot her and Nancy emails trying to get dinner, or lunch, or brunch, or five minutes on a street corner to say hi. Melissa got super involved in Occupy (and wrote a funded essay about the library which was distributed to every camp), continued to make fun of Nicholas Kristof on social media, and remained irreverent and hip. Now, she’s about to publish her new book about sex work, Playing the Whore.

I’ve continued emailing her in lowercase, never knowing exactly what to say. And I kept reading her articles and excerpts almost religiously, because in reading her work I get to know her and understand where she’s coming from. There are few people or organizations I consider truly “trustworthy” these days, and even fewer whom have the privilege to change my mind in one instant. But Melissa is one of those people. I want my work to come from wherever her work is coming from. I want it to achieve the same amicable things hers does. Nobody has ever inspired me to push as many boundaries, encompass as many perspectives, or think more critically about my activism than MGG. I feel like following Melissa’s work expands my mind and liberates me from the world we’re stuck sitting in trying to fix. I feel like it makes me a better feminist, thinker, and person to hold my own ideas and opinions up to her standards.

I have no idea where I’d be without Melissa’s feminism. And so, I asked her ten-ish questions about writing and cats and New York City. Because I still have a lot left to learn — about everything.

Ten(ish) Questions with Melissa Gira Grant

Hi, MGG!

Hello, Carmen! Let’s do this.

You’re in the finishing phases (I imagine) of your book Playing the Whore. How did that book come about, and what are you most excited about as the process finally comes to publishing?

It’s done, out of my hands at last, and off to press just a few weeks ago. The book came about quickly, after I wrote an essay for Jacobin last summer on the myth of the myth of the happy hooker. I wanted to document and question the various interests involved in insisting that any sex workers who for whatever reason still want to do sex work are both an insignificant minority and a dire threat — because they shatter stereotypes, sure, but also because they insist on speaking for themselves. Writing the essay pulled my perspective around sex work into a new focus, shifting from sex workers’ experiences (including my own) to those people who want to speak for sex workers. Anti-sex work activists, police, politicians, journalists – these people produce fantasies about sex work that bear even less relationship to sex workers’ own lives than what sex workers get paid to play out with customers. Writing this was a classic script flip.

Playing the Whore is the first book I’ve written for another publisher, and the longest and most in-depth work I’ve done so far on sex work. I kept up with my other rioting and reporting as much as possible — I went to the Supreme Court to cover a case concerning AIDS funding and sex work for The Nation, I covered a few stories related to violence against sex workers for In These Times — and all those stories fed the book, and the book gave me the long view to put these stories into context. It’s still a bit of an adjustment for me, doing work that only a handful of people could read as I went along and pulled notecards off my wall and replaced each with a thousand words or so. Maybe years of blogging ruined me, or maybe they created a productive tension. From contract to press, it took almost exactly one year. That’s basically forever in internet time. So putting the book into people’s hands already feels long overdue to me. I just want to get out on the road with it so I can make that happen over and over.

I’m super excited for Playing because I’ve always really deeply respected you for being, well, pretty much the first and one of the only feminists I have ever come across who unequivocally demanded that the experiences and obstacles of sex workers be acknowledged in and integral to my own work. I’m so grateful for that, and I’ve tried so hard to take that with me to all of my projects and it’s made me so much stronger as a feminist activist to have that perspective. How did you come to identify with feminism despite the huge differences in perspective between so many on sex workers’ rights? Given the history of feminists treating sex workers like shit throughout time, how do you feel today when you look around at the movement? Do you feel like feminism is growing to understand the complexity of sex work and respect the agency of sex workers? How do you think the movement could come to do that even more?

That’s exactly how I felt about the first feminists I read on sex work. It was really feminists writing about their own sex work experiences and politics that saved feminism for me at all, made it relevant. I remember getting my hands on Jill Nagle’s anthology Whores and Other Feminists, and then picking up Gayle Rubin and Carole Vance and Amber Hollibaugh – this was a multifaceted, queer, class-conscious feminism. In a way, it felt like a feminism that had taken sex and the body and not only gender as its leaping off point, and a feminism that grappled with everything that was pressing to me then and still is now: pleasure, danger, violence not just from individuals but from institutions that are meant to protect you. Reading Amber’s stories about going and talking about lesbian rights to union halls in California in the late 70’s? And from there, to fighting for women with HIV to be seen and taken seriously, to celebrating the ingenuity of sex workers as sex educators when no one else was doing this work? It was almost like an alternate reality, a feminism as if the sex wars had never divided us.

But to the movement question you raised — of course, the sex wars did divide the movement, and they were a class war and a sex war, as far as I understand the history. The 80’s were a moment when some feminists were getting a little bit of a power within the institutions that had denied them. I think it was tantalizing to imagine that this was the way for women to get ahead: smash the glass ceiling, wear a shapeless beige suit with a floppy tie, I don’t know, everything the Atlantic still produces cover stories saying we’re doing wrong. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that anti-porn feminism and the backlash against what was the foundation of the sex workers’ rights movement found its foothold during the same era — Reagan and Thatcher, “welfare queens” and AIDS. The beginning of the austerity politics of blame and shame, and we’re still in bed with it. But you know, girls, if we can just pull ourselves up by our Docs… or our Tory Burch flats…

I don’t know that feminism — mainstream feminism, white feminism, the kind of feminism that will get you a job as a feminist — will ever fully address sex work so long as feminism is struggling to address work, period. I expected to set a little bomb off with what I wrote for the Washington Post about the bogus “movement” Sheryl Sandberg’s marketing people attempted to launch earlier this year, but I was legitimately unprepared for how the backlash was so bourgie and so basic. Like no one thought someone might ask, how are Sandberg’s low level employees at Facebook, let alone her own domestic staff, going to “lean in” any more than they already are? As if working class women haven’t been raising this critique themselves? “Work” was the real four letter word. And it was another moment of brutal clarity: what breaks feminists down around sex work isn’t only the sex.

Prior to Playing, your big book project which moved me deeply was Coming and Crying. How do those two processes compare, side-by-side? Did you prefer editing and publishing folks’ work under your own charge or was it more fun having an editor and pushing a book through as part of Jacobin? Now that you’re extensively published online and IRL, is there a vehicle for writing which you also prefer over the other?

Thank you for that! I just put a few copies in the mail today to people — it’s still with me, always just a few feet from my desk at the very least. What’s the most common to both books is this sense of community. With Coming & Crying, that was Meaghan O’Connell (who is writing and editing now at TheBillfold.com) being absolutely original on Tumblr, and us meeting all the other writers in the same way that we met one another: through reading each other every day. There was intensity and intimacy to that on a scale that’s quite different than Jacobin, where the connective tissue was really Occupy Wall Street — that’s where I met the first writers from the magazine, and a load of other writers and editors, as well, like Sarah Leonard, the associate editor at Dissent who has done a beautiful job in pulling together a left feminist community of writers. I might type in isolation, but I don’t write in isolation.

The biggest difference is doing something DIY vs. having this institution around you. Along with the community, some of my favorite work on Coming & Crying was production – like making those important decisions with designers about which typeface both the word “fuck” and an ampersand will look best in. I still remember the day we were deciding on the stock for the end papers (a really pretty dove grey with a nice grain). Contrast that with the day I first met the publicists for my book (also different: I have publicists for my book) at Verso, and we were talking about what would go on the interior cover, and me finding out that the book was going to have French flaps – where the soft cover stock folds in on the front and the back and looks very sophisticated, I think – and since this is the kind of decision I (still) obsess over, that’s all I needed for the highly particular publisher in my head to start whispering (quietly, just to me, thank god) “French flaps? Why am I only hearing about this now?” Well, of course – I was the one with the book to write. And then it was a relief to have “only” that to do, to really appreciate all the work happening around the book that was no longer my job alone.

This is all just to say, DIY and otherwise, books are impossible without lots of people on your side.

You’re a writer with an activist’s life, which is probably why I’ve admired you for so long. That, and how badass you are. How did your activism turn to writing, and how do the two compliment each other in your work?

I like that way of putting it — a writer with an activist’s life — because I never approached my writing as a form of activism. Activism is about collective action, and in my writing, I might be one individual part of that collective, but I am not the voice of any collective, and I don’t want to be or to be interpreted that way. It’s too much to ask of one person.

I also want to resist the ways in which feminism has been defined by its attendant media, by the comparatively tidy handful of feminists who make it in media versus those who I would say are doing the work of feminism, including those who do not identify with feminism. And just as it’s not a victory to usher more women into boardrooms, let’s not mistake more women on the masthead for feminism, either, if they’re just doing the same stories in the same ways.

Before I made my living as a writer, I worked within formally structured groups with activist missions — whether that was a union shop, or a health clinic, or even philanthropy — where the goal wasn’t just to get this contract, or provide this exam, or make this grant, but in being reflective and intentional about the way we did that work, being real about who that would build power for and how, and trying to understand what would be left behind long after we weren’t in the picture. I still bring that reflection to my work, which, in journalism — is that activism? Compared to a lot of journalism, probably. But does that make me an activist? I don’t think that does. I’m not shying away from that label, as if there’s something wrong with being an activist, but I don’t want to represent what I do as activism, when I compare it to the work of people who are out there organizing, caring for their communities.

What’s your advice to any up-and-coming writers reading this piece? How did you turn writing into a successful career? What’s your writing process look like every day? How do you decorate your desk? This is all important.

Become deadly practical about risks: risks in your work, yes, but also the risk of work — getting it, keeping it, losing it. And no one takes risks alone. We all need to work at building a community where we can take the kind of risks that build us up.

I’m working with Sarah Jaffe right now on a project about writing and money, which in part gets at the idea of risk — the risks we take, the riskiness of writing as a profession, the difference between our risks and the risks that make up the lives of people in our stories, and the risks we also share together.

Risk is something I’m more comfortable holding out a few inches from my own life and thinking through than something like “success.” You can’t judge a writer’s success by their bank balance, but neither can you judge their bank balance by where they’ve been published. None of this correlates neatly. As Molly Crabapple said, “A decade of practice honed my talent. But cash let me express it.”

In my work, I’m ritualistic, but the rituals change over time. Since I moved to New York from San Francisco, my mornings are dealing with just enough work-related email on my phone in bed to get to coffee at my kitchen table, putting lists of what I need to do together on paper, and then once that’s in order, to my laptop where I imagine I will be guided by that list. Sometimes that’s strictly true: follow-up on an edit, send a contract in, schedule a phone interview for later in the day, translate a few of the rough notes in my file of possible stories into new pitches. I’ve got blocks of time each day that I work to protect from the work that goes on around my work (correspondence, accounting, all of that) so that I can actually write. That’s how I boss myself around: do what needs to get done to get to that time, to what feels like my time.

I post a photo of my current desk in each of my email newsletters, but it’s always got a stack of books pulled from my own library for whatever I’m working on (right now, that’s a lot leftover from Playing the Whore that I haven’t put away yet, plus a copy of Trisha Low’s The Compleat Purge and a CIA book I borrowed from my boyfriend), my to-do list, a souvenir brass brothel coin (“good for all night”), my notebook of the moment, and on cardboard sheets that came packed in with a shipment of records some hand drawn wireframes for my website, and some Sharpies, and knocking all that around — the cat.

Can you tell me a little bit about your cat. Anything, really.

She’s almost three, I think. I adopted her two days before the raid on Occupy Wall Street. Her name is Valerie Solanas and her new favorite place to sleep is on a black tutu in the back of my closet.