Hello! Welcome to BOOK CLUB DAY! By now you’ve all completed, I hope, The Miseducation of Cameron Post. Maybe you cried in line at the grocery store with one hand gripping your kindle and maybe you cried in your bed on a Saturday morning and maybe you didn’t cry at all while reading it but maybe you laughed a few times, or maybe both. Definitely if you read the same book I read, you closed it wishing it wasn’t over. You closed it wishing for a sequel or even more of the same.

I think the experiences in Cameron Post are familiar to so many queer women — the rural isolation from lesbian culture, the crush on the straight best friend, the religious relatives with prehistoric ideas about homosexuality — and already so many of you have told me how much you relate to Cameron and how her story connects with yours. That’s how I felt reading the book too, except backwards — it was you I thought of when I read this book, not me. If I was in this book, I wouldn’t be Cameron, I’d be Lindsey Lloyd (although that would’ve required substantially more confidence and self-awareness than I actually possessed as a teenager). I can relate to the tragic and sudden death of a parent, but outside of that I was looking at Cameron from the outside, maybe somewhere near where Lindsey or Margot were looking from.

I fell in love with Cameron and with this book pretty early on, just as I would’ve if I’d known her in real life. Because she has so many feelings and she’s trying so hard to figure everything out and isn’t afraid to dig and dig and dig until she gets it. I think that’s part of what makes queer women so awesome, eventually, is that we’re forced by design to develop a really strong relationship with ourselves. We’ve never just “fit right in,” and that experience of being slightly apart makes a person really develop into a brilliant, complicated thing.

So it is with great lovely excitement that I present to you this fantastic and totally epic Cameron Post Post, which contains answers to your questions. Everybody who sent a question for Emily was entered in our drawing to win a Lindsey Lloyd care package and on the last page of this Q&A we’ll tell you who got drawn via Carrie’s Magical Random Number Generator.

Emily Danforth answered 38 questions for you, so I recommend getting some tea, coffee or whiskey, maybe sitting on your couch, sharpening your fingertips, wiping off your eyeballs, and sitting down to read one of my favorite things we’ve ever put together for you here on this website. There’s lots to talk about, and we hope that you will — Emily’s got some questions for you in here and I have a lot in my head, like “what was your favorite part?” and “who broke your heart the most?” but those aren’t as interesting and complicated as what we’re about to get into.

So, without further ado, Emily pontificates on the coming-of-age-novel, the writing process, the book acceptance and publication process, word processing programs, queer politics in literature, lesbian pop culture, Dorothy Allison, Taco John’s… and the possibility of another book that picks up somewhere after Cameron Post left off. (!!!!!) Basically it’s the best treatment ever to Novel Withdrawal.

I loved the balance of the authenticity of the dialog and interaction between the protagonist and her peers, and the heady, often heart-wrenching introspection from Cameron. How did you approach writing for an adolescent narrator without coming off as precocious?

Thanks very much for saying so, glad that all worked for you. For me it comes down to understanding how characterization works, in-scene, and then complementing/complicating that with strategic usage of POV in the passages of narration. Cam as storyteller is a bit older, and a bit wiser, a person, one with a more developed sense of perspective on the things she’s telling you about, than is Cam as character in scene, and I was always trying to remind myself of that and use it as a potential place for tension-building in the novel.

I see Cam, the person telling you, the reader, this story, as maybe a twenty or twenty-one year old, so she’s put some of this behind her, or worked it out, I suppose, in order to be able to now tell the story to you. But, I think her narration also reveals some of the ways in which she hasn’t yet processed all of these experiences as fully as she might pretend to, and, in fact, telling the story is helping her to do some of this processing. This is her “reflective distance” from her own past, and utilizing that distance, that slightly older, introspective voice, throughout the novel, was all pretty strategic.

“Sometimes when people ask me why I write, I tell them that it’s because I grew up gay (very gay) way out in the middle of cowboy country in the windswept and dusty badlands of eastern Montana.”

However, sometimes I had to mute that reflective voice when Cam was remembering a specific moment that would become a scene in the novel—or at least turn the volume way down on it—to better help you, as a reader, just be there in those moments with her. It’s a tricky negotiation and it doesn’t work the same for every scene in the book. Sometimes she’s doing quite a lot of narrative “interpreting” as she’s showing you this scene, other times she’s just painting the picture for you. Mostly it’s just honoring your characters, in this case, my main character, and trying to present her as wholly as possible, not to pander to a certain ideal of type, or to use her as a puppet serving my plot, but to attempt to honor Cam’s humanity on the page. That sounds sort of silly, maybe, but it’s as accurate a piece of my process as I can explain it.

Where do you live now? How do your Montana roots impact your queer identity?

I live in Providence, Rhode Island—a city I love. We’ve only been here for a year and a half but both my wife and I are completely in love with Providence. It’s such a great, small, coastal city. I’ve always been really drawn to New England, for whatever reason (too many John Updike/John Irving novels…) and if we don’t live here forever, for always, it will likely still be somewhere coastal (the Pacific Northwest is very nice, too.) But, despite that, I think I’ll always consider myself a Montanan. All of my most formative years were spent there, and the whole of my immediate family still lives there—which means I’m back in MT at least once a year, often more than that. And I long for it, I do, when I’m away for too long—that landscapes works itself into your very being, I’m telling you, it haunts you until you return and get your fix. I wrote a little about this awhile ago, at least how growing up in Miles City affected me as a queer writer. Here’s how I put it then:

Sometimes when people ask me why I write, I tell them that it’s because I grew up gay (very gay) way out in the middle of cowboy country in the windswept and dusty badlands of eastern Montana. I don’t know that this answer is very satisfying to anyone. Sometimes people chuckle, uncertain. Sometimes they cock their heads, ask me to elaborate. Sometimes they just nod knowingly (you know how some people do that). What I think I mean by that answer, though, is that falling in love and in crush with other girls in Miles City, Mont. in the 1990s felt so fraught and, frankly, dangerous that from the ages of 8 to 18, closeted-me inhabited a very active and wholly imagined fantasy world in which a braver, not-closeted-me, was, well, braver and not closeted. All this time spent imagining other worlds, and other versions of me in those worlds, was eventually good fuel for fiction writing. But more than that, growing up this way — which is to say, growing up in the closet — kept me on the periphery of so many of the crucial rites of American adolescent passage: first dates and kisses and dances, those formative individual events, most of them small, to be sure, but you add them all up and there’s real weight there for those of us who missed out on all of them.

So, you know, there you go. All of that experience was formative for me, as a writer, as a queer, as a queer writer.

How much of the book was based on research? Could you talk about any research that you did? What, if anything, was the book based on and what inspired it?

How did you go about researching the “conversion” school Cameron is sent to?

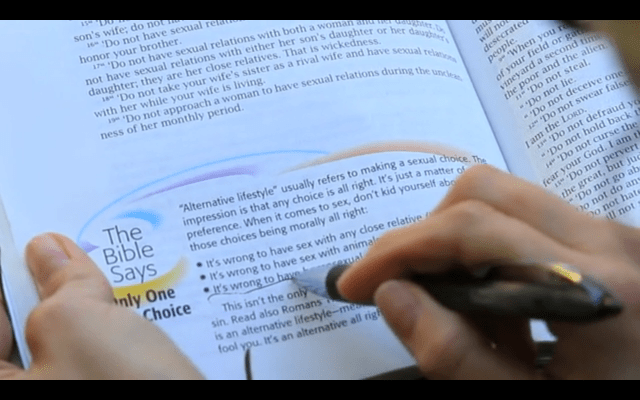

Much of the “treatment” focused on in the God’s Promise section comes from actual research I did. That research took many shapes and forms. I read all kinds of books from various practitioners of these therapies (and ordered materials directly from Exodus International, an organization that’s really changed its rhetoric in recent months, but that remains in its function as a referral network for many ex-gay ministries—despite that even they have now mostly parted ways with that term); I also spent hours and hours combing the websites and blogs of these ministries and practitioners, and also folks who themselves claim to be “ex-gay” or who have just spent time on the receiving end of conversion/reparative therapy, (And I had one on one conversations with many of these people, in chat-rooms or via email.)

I even got access to the offical application materials and “residence manual” for a live-in reparative facility for adults in Kansas. (The dorm manual in the middle of the novel is based on those materials.) I watched several documentaries on the topic, too, including the excellent One Nation Under God (1993—directed by Teodoro Maniaci, Francine Rzeznik and not to be confused with the 2009 film of the same name, also a documentary.) It was a particularly useful film, not only because it’s a documentary, but because it’s from roughly the same time period as the novel. Exodus International was just Exodus back then, or Exodus Ministries (no International component), and it has changed significantly, as well, between the time period covered in the novel and today, so only using recent resources just didn’t make sense given that Cam’s world is one from twenty years ago.

However, the facility itself, as built in the novel—God’s Promise–is an invention, it’s fiction—there is not specific school or facility that it’s based on. The practices that happen there, yes, but the place is my own, one born of my research.

As for inspiration, shoot, that’s impossible to answer, really. It’s inspired by so, so many things, from novels I’d read to music I love (or once loved) to films, my own memories, the landscape of Montana, growing up in the closet, being horrified by conversion therapy and its practitioners. I can’t pin any of that down to one satisfying answer. It was my first novel and it had been bubbling away inside me for a very long time, its points of inspiration are many.

Did you have someone like Lindsey Lloyd in your formative years? Or have you been that person to someone?

I didn’t have a Lindsey Lloyd type figure in my life until college, sad to say, and by then I was old enough, had experienced enough, that she didn’t have quite the same effect on me as she did on Cam—or as she would have on me had I met her at 12 or 13, or even 14 or 15. But, still—there were a couple of friends who I met early on in college who introduced me to some aspects of dyke culture that I was unfamiliar with, absolutely. My best “fairy gay,” though, was/is my friend Ben. We also met in college. I was already out and he’s no lesbian, but we did proclaim ourselves the school’s “favorite gays,” and then worked really hard to live up to that self-bestowed title, mostly by throwing lots of parties. If it sounds like gross behavior it might have been, I’m afraid, but we simply did not care. (Mostly because we were drunk.)

I would have LOVED to have had a Lindsey Lloyd in my life in high school, despite some of her (delightful) flaws. A Lindsey in high school would have saved me some heartache, I’m sure. I don’t know that I’ve specifically been a lesbian fairy godmother to anyone, the “keeper of the light of dyke knowledge,” I mean, but I did spend a chunk of my early twenties as a kind of Lindsey Lloyd. I see a lot of my 19, 20, 21 year-old self in that character. That’s not an entirely good thing, maybe, but it’s true.

As a queer writer, do you consider your work necessarily political? Would you ever write a book that didn’t focus on queer issues, or do you feel as though part of your mission/responsibility/identity as a writer is wrapped up in being queer?

Certainly I’m used to my sexuality as being understood, by many, as political—that’s just part of any out queer’s current experience. (It’s not, frankly, fundamentally understood by me that way, but I live in a culture and at a time wherein any non- heteronormative desire or embodiment is necessarily political. The very recent election and the great successes for marriage equality (and queer representation in congress) indicate a real kind of progress in terms of shifting political views, nationally, on issues that pertain to lesbians and gays, but it’s also one that’s easy to problematize given all that’s bound up, politically, in the institution of marriage, no matter the gender of those getting married—but it’s social progress nonetheless and I appreciate it as such.)

All of this is to say that heteronormativity makes any exploration of queer desire in a work of fiction political for some readers, while at the same time some explorations/representations feel not nearly political or politicized enough for other readers (often, unsurprisingly, queer readers.) One of the things I’m most interested in exploring when I write fiction is desire—romantic, sexual, even aesthetic. Desire is so often messy and complicated, even fraught—it’s good material for fiction. And what I know best is queer desire, so I’ll always, always be writing about that. Guaranteed.

I wanted it to be a great big coming of GAYge novel, one that both represented the literary traditions/tropes of the American coming-of-age novel and also one that queered some of those traditions, or answered back to them, subverted them.

I wanted Miseducation to be a great big coming-of-GAYge novel, one that both represented the literary traditions/tropes of the American coming-of-age novel/novel of development, and also one that queered some of those traditions, or answered back to them, subverted them. As such, it necessarily explores the formation of queer identity(ies) in a fairly microscopic and chronologic way. I’ve now written this novel, though, and I’ll never write it again. (Unless, I suppose, I ever write Cam’s continuing adventures, which would be its own novel, but would tread in similar territory.) What I mean is: I won’t again write a novel that’s structured as a coming-of-age novel, a novel that explores queerness in quite this way. It’s always been important to me that each successive novel I write take a new approach in terms of structure, in terms of construction (and of course in terms of plot and content), though undoubtedly some themes I’ll return to again and again. However, I’m writer that deals in specifics.

Like Dorothy Allison, I want my fiction to “break down small categories,” to feel authentic and powerful in the specificity of its rendering. Allison also said “some things must be felt to be understood, that despair, for example, can never be adequately analyzed; it must be lived…”

She’s talking, of course, about the power of literature to transport readers not only to different times and places, but to different selves, to emotional landscapes that cannot be effectively discussed in, say, academic speak—and that’s a power that I seek to utilize in my own fiction. Audre Lorde famously wrote, “There’s always someone asking you to underline one piece of yourself – whether it’s Black, woman, mother, dyke, teacher, etc. – because that’s the piece that they need to key in to. They want to dismiss everything else.” I believe that one of the powerful things character-driven fiction can do is offer narratives that refuse those kinds of dismissals, that kind of essentialism.

In the novel, many characters are presented sympathetically and multi-dimensionally, including those who are using religion as an excuse for intolerance. Was it difficult to create those characters who were prejudiced?

This was something that was pretty crucial to me as I wrote—getting these characters to feel multidimensional on the page. Aunt Ruth, for instance, was a character who went through substantial revision as the drafts piled up, and I’m still not sure she’s as complicated/compelling as I’d ultimately like for her to be. I absolutely did not want the evangelical Christian characters in this novel—even those running God’s Promise—to be merely zealot-puppets that I could manipulate in scene to reveal my own views and agenda.

However, some readers of early drafts called me out for writing caricatures and not characters, and I think those criticisms were pretty fair. No surprise that it’s challenging to authentically and fairly treat characters (on the page) who espouse viewpoints and live ideologies that you so vehemently disagree with. I revised several scenes because I kept making those characters, in my novel, too one- dimensional and cartoonish. (The problem being that it’s hard for me not to experience most zealots, in life, as cartoons, even as I see them in front of me on TV or on the street—my way of looking at and experiencing the world is just so removed from any of that—so it was a personal challenge to try and move beyond that kind of portrayal in my novel.)

How did you develop your prose style? Were there any writers who were particularly influential of your style?

I developed it by reading a whole lot and writing a whole lot, and, importantly, thinking pretty critically about craft, but then also purposefully not thinking much about it, frankly, when I sit down to do early drafting. I can think more strategically about technique when I’m revising, but in its early stages my fiction doesn’t come from craft, it comes from ideas or memories, from small moments of this or that—the nostalgic potential of a particular smell, a bit of conversation I’ve overheard, some grievance or terror or piece of a tragedy—that I want to “get at” in fiction. I studied fiction, as a craft, in a couple of graduate programs and unquestionably all of that careful attention paid to fiction—and the workshopping process—helped me to refine my style. (Though if I look at pieces of my writing from my late teens, early twenties, that style—some of my preferred usages of technique, that is, my stylistic tics, are already emerging.)

There are many, many writers who have influenced me, though I don’t know that it would be correct to say that they’ve influenced my style, in specific. In particular I’m drawn to Steinbeck’s ability to render place; to Sarah Waters’ colorful treatment of history and her always delicious plots; to Nabakov’s sentences; to Roald Dahl’s wit and villains; to Flannery O’Connor’s southern Gothicism and penchant for (grotesque) violence—particularly in her short fiction.

Before writing Miseducation… I really steeped myself in (mostly late-twentieth century) coming-of-age novels, and Janet Fitch’s White Oleander; Wally Lamb’s She’s Come Undone; Jeffrey Eugenides’ Middlesex; and Curtis Sittenfeld’s Prep were all equally influential. (As were books from much earlier in the century, or even before, including Catcher in the Rye, Rubyfruit Jungle, and Susan Warner’s sentimental “classic” novel of instruction, The Wide, Wide World.) If I could pick one novel, though, that I wish I’d written, that I wish I could claim, it would absolutely be Michael Cunnigham’s The Hours. I think it’s pretty much a perfect novel.

If Cameron was losing it for Coley in 2012, what movie-of-seduction would she bring to the apartment that fateful afternoon? Still The Hunger, or has the cinema of the last twenty years made a new offering?

Ha!–fun question. Unquestionably there are now more (and better) films with some sort of Sapphic bent for Cam to choose from than there were in 1991. And TV shows and webisodes too, for that matter. It’s all a question of perspective and intent, I think. The Hunger works well for Cam in her particular situation because she has it on hand, for one, and saves time skipping a stop at the video store before heading to Coley’s, but also because while of course she knows there’s going to be some ladies making out in it, she can present it to Coley as just a “wacky vampire story.” And then she gets to enjoy the moments in between, once she’s pressed play, while Coley figures out the other layer to this film—the one that Cam hasn’t mentioned. (Also, it was historically appropriate for my needs as a novelist.)

All of this would necessarily play out quite differently today, given how much more visible (and accessible) are various kinds of LGBTQ representations in our current popular culture—as problematic as some of those representations might be for some of us. I belabor this because Cam’s choice is in some ways made easier—there’s more material to choose from—and also more difficult, for that very same reason. Would she want to pick something that she still thinks Coley wouldn’t be familiar with? So maybe an indie movie? And does she go for a true romance between women, or is just a sex scene between women enough? I mean, if she wanted to hit the nail squarely on the head then it’s, what, an episode of The L Word? (Or now The Real L Word.) That just seems too on the nose to me. She’d probably go for something wherein a seemingly straight woman falls for another woman, but also something that doesn’t feel too complicated or demanding of its viewers, and features youngish protagonists. Maybe D.E.B.S. or Kissing Jessica Stein (but skipping the awful last five minutes of that film, just ending it early, when they’re a happy, functioning couple dancing around to music) or Saving Face. But I’m a Cheerleader or Imagine Me and You might work, too.

Or Bound. When in doubt there’s always Bound, right? It might be perfect for Cam’s intentions, actually, because there’s this complicated crime plot to latch on to, so she could easily present it to Coley “just” as a mob film. Or she could always cherry pick a couple of the Willow/Tara episodes of Buffy. Or just pull up one of the 900 clip reels of lesbian moments in film on youtube (though where’s the fun in that?) One of my very, very favorite films exploring young, fraught, imperfect romance between teenage girls is Lukas Moodysson’s quiet Swedish film Fucking Åmål (which was released in the states as Show Me Love.) That might, in fact, be the absolute perfect choice (though they’d have to contend with the subtitles, which could make following the narrative tricky if they’re simultaneously trying to make out. I’m sure Coley and Cam could figure it out, though.)

So, final answer: Fucking Åmål. If you haven’t seen it you should, it’s incredibly tenderhearted and touching and honest.

This is somewhat embarrassing to admit (and I’m sure you weren’t expecting this follow up when you asked the question), but on one of my very first official dates with the woman who would become my wife—I say official because we’d been friends who had not dated for several years prior—we watched “The Puppy Episode” of Ellen. Anyway, get this, a friend of mine had taped this episode for us—off of the Lifetime network, of all places—because I didn’t have a TV (let alone a VCR) in my dorm room. I was a closeted high school kid when the series was on the air, and so had not tuned in, nor had my wife (though I’d seen “The Puppy Episode” by the time we watched it together on this date), but this very good friend made me two VHS tapes of the final two seasons as a kind of “welcome to your gay life” present, I guess. I still have those tapes, actually. (Despite that I have no longer have a VCR on which to play them.) Anyway, I love the image of the two of us on our first date, sitting on this twin mattress in somebody’s dorm room watching Ellen come out: it’s such a cliché. You’d think we’d have headed to an Indigo Girls concert immediately afterward. (We did not.) I don’t think, however, that I intended it as a potential tool of seduction. I just thought it was funny and that we’d like it (and we did.) I think we might have held hands while watching it. That’s how sweet we once were.

NEXT: On Religion-by-VHS, writing software, the autobiographical elements of the book, Coley Taylor’s sexuality and more!

+