Feature image via Harkey Science

When I was living in France back in 2009, I taught English at a university that catered only to computer science students. Ninety percent of my students were male. I had only three female students during my four months as an English tutor. My male students referred to their female colleagues as either chaste workaholics or whores who would sleep with anyone to avoid doing work to get to the top. This was not my experience with the female students. When one of my students told me that homosexuality was a sin against God and that women belonged in the kitchen, I had had enough. I made them sit in a circle on the floor and we had a discussion about feminism. None of my female students were present at the time. When I asked them why there weren’t more women at the school, none of them pointed to the way they treat women in the classroom. None of them even considered that their assertion that they’d love to see more women at the university because they’d love to date them even remotely a detractor for women choosing what to study and where to study it. They all told me that women just are not innately interested in science, and in fact they weren’t innately good at it.

Dr. Ben Barres studies and teaches neurobiology at Stanford, with a focus on neuron-glial interactions in the development of the central nervous system. He graduated from MIT back when he was presenting as Barbara Barres, a period of his life he has no problem with speaking about publicly because he believes it gives him an interesting insight into the increasingly covered dearth of women in science. The Wall Street Journal very recently published an article about Dr. Barres’s take on the subject. It’s worth noting that the Wall Street Journal coverage has some semi-problematic language, headline included. However, some of the language comes from the way Dr. Barres himself speaks about and frames his own transition. You do you, Dr. Barres! The truly important thing is that the article is rife with anecdotes of the differences between Barres’s treatment from others when presenting as female versus when presenting as male. For instance:

Ben Barres had just finished giving a seminar at the prestigious Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research 10 years ago, describing to scientists from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Harvard and other top institutions his discoveries about nerve cells called glia. As the applause died down, a friend later told him, one scientist turned to another and remarked what a great seminar it had been, adding, “Ben Barres’s work is much better than his sister’s.”

Dr. Barres does not have a sister. In fact, the scientist was remembering Dr. Barres in previous years. Same research. Same person. But he was taken more seriously while presenting as male. This is an experience many of us feel personally every day, regardless of which field we work in.

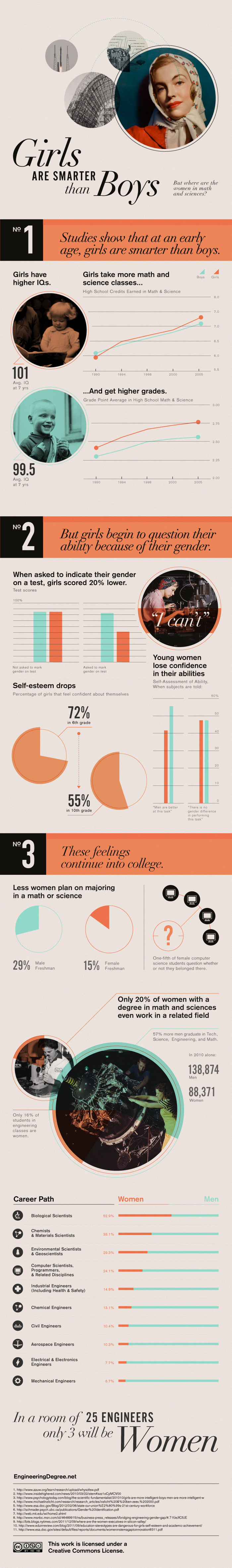

The interesting thing about Dr. Barres is that, unlike me, he’s not working off of personal anecdotes alone. He’s a scientist and he knows about brains. He looks at the data to refute the claims by Larry Summers, a former Harvard president, that women have a lack of “intrinsic aptitude” for math and science, and that’s why there aren’t so many women at the top level. Barres asserts that there are no differences in cognitive ability between the sexes, but rather the treatment of women accounts for the gender gap in scientific field and that the under-representation of women in the professoriate is entirely based on social factors.

This is not news for us. It’s clearly not news for Barres. He lectured on the subject in 2008, and you can see the entire two hour lecture and even have the slides all for yourself, which I highly recommend. He’s also backed up by other sources, which say that when women are reminded before an exam that they are supposed to be worse at science by being asked to indicate their gender, they do worse on that exam.

So what should we do about it? “Ask to see the data,” says Ben Barres in his lecture. Assumptions about women, even the ones we’ve all grown up hearing, are rarely backed by the data that is cited in these so called studies. And he tells all of us women in academia to ask for what we need and take it upon ourselves to tackle stereotypes and prejudices where we see them. This is certainly something we can extrapolate and take to heart in our every day lives, scientists or not.