June is LGBT Pride Month, so we’re celebrating all of our pride by feeding babies to lions! Just kidding, we’re talking about lesbian history, loosely defined as anything that happened in the 20th century or earlier, ’cause shit changes fast in these parts. We’re calling it The Way We Were, and we think you’re gonna like it. For a full index of all “The Way We Were” posts, click that graphic to the right there.

Previously:

1. Call For Submissions, by The Editors

2. Portraits of Lesbian Writers, 1987-1989, by Riese

3. The Way We Were Spotlight: Vita Sackville-West, by Sawyer

4. The Unaccountable Life of Charlie Brown, by Jemima

5. Read a F*cking Book: “Odd Girls & Twilight Lovers: A History of Lesbian Life in 20th-Century America”, by Riese

6. Before “The L Word,” There Was Lesbian Pulp Fiction, by Brittani

7. 20 Lesbian Slang Terms You’ve Never Heard Before, by Riese

8. Grrls Grrls Grrls: What I Learned From Riot, by Katrina

9. In 1973, Pamela Learned That Posing in Drag With A Topless Woman Is Forever, by Gabrielle

10. 16 Vintage “Gay” Advertisements That Are Funny Now That “Gay” Means “GAY”, by Tinkerbell

11. Trials and Titillation in Toronto: A Virtual Tour of the Canadian Lesbian & Gay Archives, by Chandra

12. Ann Bannon, Queen of Lesbian Pulp Fiction: The Autostraddle Interview, by Carolyn

13. 15 Ways To Spot a Lesbian According To Some Very Old Medical Journals, by Tinkerbell

14. The Very Lesbian Life of Miss Anne Lister, by Laura L

15. The Lesbian Herstory Archives: A Constant Affirmation That You Exist, by Vanessa

16. I Saw The Sign: Queer Symbols Then and Now, by Keena

17. The Ladies Of Llangollen: Runaway Romantics In 18th Century Ireland, by Una

18. 15 Awesomely Named Yet Totally Defunct Lesbian Bars Of America, by Riese

19. 6 Special Ideas About What Lesbian Sex Is, 1900-1953, by Party In My Pants

20. Queering The Library: Collecting Downtown, Riot Grrrl, Feminism & You, by Vanessa

21. Six Ways that 1950s Butches and Femmes Fucked with Society, Were Badass, by Laura

![]()

Butches and femmes may have started to get a lot of flack in the ’70s for (allegedly) subscribing to heteronormative roles within their relationships, and nowadays, when I wear my requisite polka-dot dresses and heels, I might feel like screaming, “I’M NOT HER STRAIGHT FRIEND!” to everyone at every gay event, ever. But in the mid-twentieth century, butches and femmes ruled the roost (or at least the dyke bar scene), for better or for worse. They also paved the way for tons of fantastic lesbians, radical queers, revolutionary feminists, and really awful (and awesome) hairstyles that came after them. My thesis? They were totally badass.

1. Butches were butches, femmes were femmes…

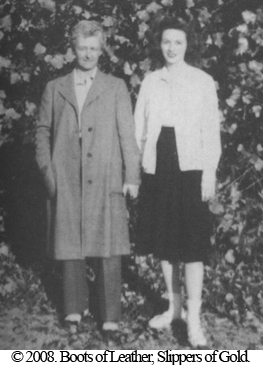

The butch/femme system wasn’t just a sexual preference or a preferred style of dress; in most lesbian circles, it was a social imperative. It was most prominent in working-class circles, where the privilege of discretion was not so readily available as to the upper class; where butches could work in blue-collar jobs that didn’t require them to wear feminine clothing; and where both femmes and their more masculine counterparts tended not to have professional jobs in areas that would require them to project a particularly middle-class brand of moral “purity” (you can read all about this, by the way, in the fantastic Boots of Leather, Slippers of Gold, by Kennedy and Davis, which my girlfriend lent to me and which she thinks I will be returning; she is wrong). Roles were generally fairly rigid, at least at the outset, and at least with the lights on. In fact, many gay women identified as butch or femme before, or even instead of, identifying as gay, homosexual, or lesbian. Butch-on-butch and femme-on-femme relationships were often kept hush-hush.

The butch/femme system wasn’t just a sexual preference or a preferred style of dress; in most lesbian circles, it was a social imperative. It was most prominent in working-class circles, where the privilege of discretion was not so readily available as to the upper class; where butches could work in blue-collar jobs that didn’t require them to wear feminine clothing; and where both femmes and their more masculine counterparts tended not to have professional jobs in areas that would require them to project a particularly middle-class brand of moral “purity” (you can read all about this, by the way, in the fantastic Boots of Leather, Slippers of Gold, by Kennedy and Davis, which my girlfriend lent to me and which she thinks I will be returning; she is wrong). Roles were generally fairly rigid, at least at the outset, and at least with the lights on. In fact, many gay women identified as butch or femme before, or even instead of, identifying as gay, homosexual, or lesbian. Butch-on-butch and femme-on-femme relationships were often kept hush-hush.

Personally I tend to cringe at anything that includes the word “imperative.” But the badass part about this? These were females. Women. With enough differences between them to eroticize them. To create an erotic system that was, in fact, all their own, with its own norms, values, and sexual practices and mores. Without Finn Hudson (I mean, dudes). Most butches weren’t trying to pass for men; they were trying to SURpass them. Perhaps even more importantly, a butch-femme pair, arm in arm on the street, was the number-one symbol of lesbianism, and maybe the only recognizable symbol of the lesbian community, of the era. To be butch or femme meant to be recognized by your own people. It meant visibility. It meant that you were known.

2. …except when they weren’t.

Creating your own system has its pitfalls, one of them being that you now have to operate within a system. As per usual, plenty of queer women subsequently fucked with said system, with femmes switching to butch (and vice versa) and back depending on the week, the evening, or the mood. The roles stayed the same (though butch-on-butch relationships, with the tight butch community formed at bars, were not uncommon either), but slipping in and out of them at will revealed their true fluidity.

The gender dance between butches and femmes themselves had its own issues; both sides were prone to jealousy, and, without the legal protections or social expectation of marriage, issues of control and adherence to monogamy abounded. The idea that femmes were passive recipients of anything, though, is verifiably ludicrous. Butches, with their questionable attire and mannerisms, were often under- or unemployed, and femmes often had to bring home the bacon–and many did so, willingly, choosingly.

3. They looked damn good.

The rest of the world may have thought butches, with their Duck’s Ass haircuts (no, really) and various manifestations of period male getups, were perverts or cheap imitations of men, but their femmes certainly didn’t, admiring the girls who came in from working on the railroad and at the factory and providing validation for the unthinkable. Femme fashion was closer to straight women’s fashion, with a little (or a lot) more glamour. Looks were important, but in a way that engendered a sense of pride in the give-and-take, unique system that had been created, and in a way that was also, according to my research, adorable. Vic, a butch interviewed for Boots of Leather, explains:

“You were very proud of your woman and the woman was very proud of her butch. The woman took care of her butch in the way she always looked good. If the butch looked bad it was your fault if she did…And you were proud of your woman. You wouldn’t take your woman out with a rag on her head and no makeup on…And you didn’t leave the house without her saying you look good. There was a very deep pride there.”

4. They got theirs.

Butches, at the time, were generally assumed to be stone, meaning that they gave pleasure and did the “doing,” without reciprocation in kind from their femme (though, again, behind closed doors was often a different story). This assumption has led to a lot of valid and important discussions about butches and body dysmorphia, sexual repression, and the like, though many butches interviewed for Boots of Leather claim to get all their sexual satisfaction from pleasing their lovers (really, y’all are great). The important part here is that women were enough, in and of themselves. Butch-femme eroticism shattered the illusion that there needed to be a male aggressor or initiator, or that that type of erotic tension couldn’t exist between two women. Femmes, like my personal high femme heroine Amber Hollibaugh, have waxed poetic about finding empowerment by putting themselves into a butch’s hands. Though femmes often made love to their butches as well, or switched roles, many preferred this conscious giving over of sexual power, and found a new kind of enjoyment in the focus on their own pleasure (a phenomenon that was at the time almost unheard of for women).

Butches, at the time, were generally assumed to be stone, meaning that they gave pleasure and did the “doing,” without reciprocation in kind from their femme (though, again, behind closed doors was often a different story). This assumption has led to a lot of valid and important discussions about butches and body dysmorphia, sexual repression, and the like, though many butches interviewed for Boots of Leather claim to get all their sexual satisfaction from pleasing their lovers (really, y’all are great). The important part here is that women were enough, in and of themselves. Butch-femme eroticism shattered the illusion that there needed to be a male aggressor or initiator, or that that type of erotic tension couldn’t exist between two women. Femmes, like my personal high femme heroine Amber Hollibaugh, have waxed poetic about finding empowerment by putting themselves into a butch’s hands. Though femmes often made love to their butches as well, or switched roles, many preferred this conscious giving over of sexual power, and found a new kind of enjoyment in the focus on their own pleasure (a phenomenon that was at the time almost unheard of for women).

And you can’t talk about butches without talking about competition, with each other but also with straight men. While historically, straight men had been known to gain authority over their women with violence, butches saw the perceived competition as an opportunity to display their sexual prowess, and prided themselves on it. Society may have not wanted femmes to be in the arms of butches, but they often did when a butch took the time to really learn them, and to get them off–at a time when the (totally insane!) possibility of female orgasm was just beginning to be discussed in heterosexual marriage manuals (often as a burdensome process that required the man to bury his real urges and really, really try to want to give pleasure too, but, you know, baby steps).

5. And, like good lesbians, they processed it.

Girls who like girls like other girls who can impart knowledge. Butches and femmes were no exception, especially in the area of sex. Jeanne Cordova, author of When We Were Outlaws, has spoken about her own experiences with older butches growing up in the mid-twentieth-century, and how she learned to please a woman. Since femmes didn’t have to adhere to the same social norms as heterosexual women at the time, they weren’t expected to be virginal or inexperienced, nor were they expected to lay back and take whatever they were given. To the contrary, butches were often eager students of femmes as they were instructed on how to best please them sexually.

6. They defended their spaces. And made new ones.

The image of the “tough bar lesbian” may have been limiting in some ways, but it was also, unfortunately, necessary. Violence wasn’t uncommon, especially as suspicion about everyone from Communists to queers began to mount. Butches and femmes alike were not above confrontation to defend their spaces, physical and otherwise.

The image of the “tough bar lesbian” may have been limiting in some ways, but it was also, unfortunately, necessary. Violence wasn’t uncommon, especially as suspicion about everyone from Communists to queers began to mount. Butches and femmes alike were not above confrontation to defend their spaces, physical and otherwise.

The “outlaw” status of butches and femmes made it possible to cross boundaries, too, though. Femmes, particularly African-American ones, often served as hostesses for buffets and house parties that bridged the gap between lesbians and gay men. Though full racial integration took many more years, Audre Lorde also noted the willingness of queer women to form new, more diverse spaces for butches and femmes in a time rife with tension:

“Lesbians were probably the only Black and white women in New York City in the fifties who were making any real attempt to communicate with each other; we learned lessons from each other, the values of which were not lessened by what we did not learn.”

Though the 1950s butch-femme scene may have been a veritable gender politics minefield, butch/femme dynamics offered (and offer) a different way of “being” woman, of “doing” female. Butches were not masculine females, women “playing at” maleness. Femmes were not merely the recipients of their desire, or women attracted to other women with a little more swagger (maybe, sometimes) and a few more pairs of slacks (maybe, sometimes) than they. Our language doesn’t give us the words to describe it yet, but Carol A. Queen may have said it best in butch-anthology-extraordinaire Dagger:

“Most importantly, a butch/femme couple is queer…In fact, the more gender differentiation in their relationship, the queerer they are.”

And that’s really, really badass.

Resources:

Boots of Leather, Slippers of Gold. Elizabeth Lapovsky Kennedy and Madeline Davis. Routledge, Inc.: New York, New York, 1993.

Dagger: On Butch Women. Ed. Lily Burana, Roxxie, Linnea Due. Cleis Press, Inc: Pittsburgh, PA, and San Francisco, CA, 1994.

Comments

Fittingly, this was a badass article. Awesome stuff! As someone who is neither butch nor attracted to butches, I find the butch/femme dynamic fascinating from an academic standpoint. Undermining the Patriarchy and all that.

Great article! I love how you start with the fact that 50s butches and femmes paved the way for other queers and lesbians and that they weren’t hetero copies. Have you read the recent awesome collection Persistence: All Ways Butch and Femme, edited by Ivan E. Coyote and her wife Zena Sharman? I highly recommend it, for a contemporary look at the ever fascinating butches and femmes!

Yes, everyone should read it, it’s fantastic!!! I re-recommend your recommendation. :)

Laura, you are soooo gorgeous. Wish I could get with you hon.

Thanks for the compliment!!

this collection is amazing, highly recommended

This was great. And pretty sure I read Boots of Leather, Slippers of Gold for a class. So I probably “read” it and this piece makes me consider actually reading it. Thanks Laura!

This article is fantastic! I think I’ll pass it on!

Marvelous. I’m so grateful that there’s real study being made of queer history (even if it’s still technically in its infancy).

This article was great. Thanks for writing it!

Great article! Another book to go along with this is “Stone Butch Blues” by Leslie Feinberg.

Plus a million! Should’ve mentioned it for sure. Changed my gf’s life. Iconic book.

YEAH IT DID! (Hi Laura! Way to impress, I extra have to approve of you now!)

AND YES TO ALL OF THIS

Hi Anna! I PROMISE this wasn’t orchestrated for your approval. But it is a lovely bonus.

Happy berry picking!

tollllld you.

awww i wish this article was longer……like a huge ass wiki entry. anyway it made my little queer heart grow 3 sizes bigger

I’ve suggested that my local library buy both of these books so I can read them. Building up the queer titles one book at a time.

Side note – any other Autostraddlers in Melbourne? I’ve just moved here and am looking for gals to hang with & do stuff :)

When there were groups, Melbourners were really the most vocal subset of the Australian group, so I am confident that they are around somewhere.

I just moved to Melbourne like, today.

This was a very interesting perspective on a subject that has become so cliché at times we lose track of it’s significance. Thanks for bringing it to the table! Also, my partner and I noticed a very strong presence of butch/butch couples when we went to Pride this year and it actually got me wondering about that dynamic. It seems like it is much more commonplace in the gay community nowadays and I wonder how it has progressed. I find it interesting to see butch women who are attracted to each other rather than seeking out more overt femininity in a partner. If any of you would like to enlighten me on this topic, please do :)

awe4some article! Thanks so much!

Yes, Laura, thanks for picking up on the 60s femme in my memoir,

When We Were Outlaws. Her name, Bejo. Your article was great but doesn’t mention, back then, femmes were expected to learn how to “top from the bottom”–a skill almost lost today. Few butches were totally stone, although we swung that way, so it was good to get a femme that was truly active in bed without taking over, or just “laying back and think of England.” Really–that was the straight girl role back then. Also, we weren’t as allowed to be as fluid as you suggest. You picked if you thought you were butch OR femme, and you stayed there–unless you were in your 20s. Then, older bulls said, “Give her a break, she’s just a baby butch (or baby femme). Switching roles after your 20s was frown upon–it broke the code to be “kiki” or “AC/DC” . But yeah, we were really proud of each other as butch or femme in a world that hated our existence because it flung in the face of the Patriarchy. Now that was subversive!

Thanks so much for the info!! I saw you at Queer Memoir a few weeks back and you were great.

I want to preface this comment by saying I love and appreciate this (enormous) aspect of dyke history. My gender identity and self-identification as a femme lesbian is historically rooted to the butch/femme dynamic and I owe everything to the women mentioned in this awesome article.

What follows applies strictly to the last quote. So, I think I feel mildly dick-ish about saying this, but as a femme whose sexual/queer/romantic desire operates entirely without butch/masculine-of-centre folks (I’m attracted to femme/feminine-of-centre women exclusively) I resent the implication that a butch/femme couple would be queerer than me and a femme partner. The fact that there would be little or no gender differentiation in our relationship says NOTHING about us or how queer we are. I want revolution, I want it now, and I want to fuck in high heels. I don’t understand or agree with the math that says my relationships were less queer than other folks’ relationships because there was less gender differentiation. Frankly, I think that equation comes from a place of binarism and there are mo betta ways to celebrate the radness that is butch-femme/gender-differentiated relationships than setting them atop some weird hierarchy of queer relationships.

I want to celebrate butch and masculine identities/bodies, but I have no interest in privileging it over other identities/bodies. Imposing that hierarchy on who’s queerest, or whose relationship is queerest, based on our gender identities would pretty much be the anti-queer, amirite?!

Anyway, so much love to AS and Laura for posting this article and bringing the lives of our working-class queer ancestors to the fore.

I actually hesitated to include the quote you mention because of the use of the word “queerer,” which is obviously comparative, and I think it’s both useless and impossible to make comparisons of what is “queerer” or “less queer.” No queer relationship is truly objectively “more queer” than another, nor does it matter if it is or not.

However, I think this quote and others like it should be viewed in the context of prejudice, which in my own experience (I am femme and prefer to pair with stone butches, though I agree completely with your statement that femme identity is entirely autonomous from one’s partner; I was femme before I discovered I was queer, and I would be if I dated men, if I dated other femmes, or if I dated no one) is fairly constant, against butch/femme relationships, and accusations that they are somehow “straight” or heteronormative in nature, or that if you are feminine and pair only with very masculine individuals/vice versa, you are still oppressed by the patriarchy and are simply acting out patriarchal gender roles with someone of the same sex. Because of my femininity, but also because I partner with masculine females, I am often accused of being a confused straight girl or not “really” queer, while my girlfriend (and other butches) is accused of “trying to be a boy” or “acting like a boy/trying to pass as a man.” (And as a side note, while I would never deliberately celebrate butch or masculine female-identified bodies/identitites/individuals over any others, I do recognize my own privilege in that society, albeit often for the wrong reasons, considers my appearance to be acceptable and often does not consider the appearance of masculine-of-center females to be acceptable.)

So, while I agree with most of what you are saying, I think that this quote isn’t coming from a place of privileging butch/femme dynamics or holding butch/femme relationships up as the prototype of queerness against which other queer relationships should be measured; rather, I think she is pointing out that gender differentiation between females is STILL queer, VERY queer, that masculinity and femininity do not a man or a woman make (and vice versa), and that gender presentation and sexual orientation are not at all the same, which many, many people still do not assume or believe.

Thank you so much for your comments! They really made me think; I am still trying to figure all of this out and I welcome anything that makes me think about/rethink my views or my own biases.

Oooooh, gotcha! So, the quote is getting at butch-femme relationships being the opposite of heteronormative, not the “queerest” in opposition to OTHER queer relationships (am I getting that right?). I dig that angle and totally hadn’t thought of it that way, which is why it’s soooo important to talk about this stuff and to people who’s experiences are different from one’s own. I really wouldn’t have gotten that out of the quote had you not brought in your perspective. Excellent stuff!

Thanks for the feedback and the awesome article, Laura.

p.s. http://www.femmetech.org/2012/06/deprivileging-invisibility/ <—For further femme reading!

Yes, exactly! Or at least that’s how I interpreted/used the quote, that a masculine/feminine dynamic in a relationship does not make it an imitation of a heterosexual relationship, nor are butches trying to ape maleness or be ‘pale imitations of men,’ of which they are often accused (because we totes all either want men or want to be them). It’s a reaction to, ‘so is she the man and you’re the woman?’

So I’m super glad you pointed out that possible interpretation. I can get very steeped in my own experiences as well and make assumptions. So yay, productive dialogue, thanks for the reading, and yes, fucking in heels goes great with the revolution. I agree.

This article is fantastic. Also, “Without Finn Hudson (I mean, dudes).” A+

I looove running into articles about the butch/femme dynamic.

Time to add more to my reading list.

c:

Loving you so hard right now, guys.

great article. since i came to the realization that not only was i a lesbian, but a femme, i became more comfortable in my gender identity and am more feminine now then i was when i identified as a straight girl. i love researching the lives of my lesbian predecessors and “boots of leather, and slippers of gold” was a fantastic read with interesting pictures. i’m still on the fence about how racially intergrated the lesbian community actually was back in the 1950’s considering that the lesbian community can be pretty racially segregated today.

I enjoyed ‘Queer Memoir’ very much. It touched my heart.

this trully brightened up my 14 hour hell shift! I wish there was a way I could explain this in one “slap in the face” sentence everytime my mother asks ‘why I want to look like a man’ gender roles don’t exist mother wearing a tshirt and pants doesnt make me male!!

please tell me more about the color options as I explain how the motor works….

[…] Six Ways that 1950s Butches and Femmes F*cked with Society, Were Badass (2012) […]

[…] the 1950s lesbian community, butch and femme women were often assumed to pair up, with butch/butch and femme/femme couples often shamed by others. Obviously, that archaic […]

[…] the opposite was usually true. Along with that, presently, lesbian tradition was once, in fact, dominated by a binary understanding of sex and gender that was once liberatory for some and exclusionary for others. After all, as tradition modified, […]