June is LGBT Pride Month, so we’re celebrating all of our pride by feeding babies to lions! Just kidding, we’re talking about lesbian history, loosely defined as anything that happened in the 20th century or earlier, ’cause shit changes fast in these parts. We’re calling it The Way We Were, and we think you’re gonna like it. For a full index of all “The Way We Were” posts, click that graphic to the right there.

Previously:

1. Call For Submissions, by The Editors

2. Portraits of Lesbian Writers, 1987-1989, by Riese

3. Vita Sackville-West, by Sawyer

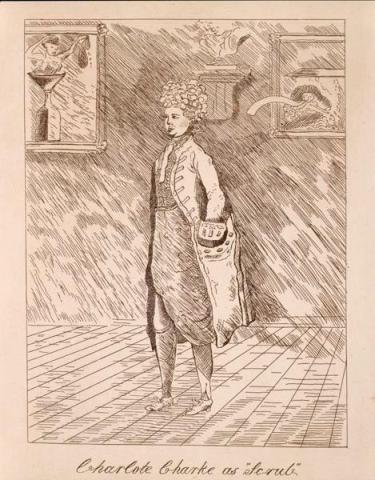

4. The Unaccountable Life of Charlie Brown, by Jemima

![]()

Here’s an important question you probably haven’t asked yourself often enough: if you were a queer timehacker living in the future, what would you do to history? I have a plan. I anticipate that, within the next seven or eight years, a kooky scientist with cute glasses will inadvertently stumble upon a programming code enabling us to alter the course of history.

Anyway, the point of this is that there is an individual in queer history for whom I feel so much affection that I’m pretty sure I invented them. I think we often have the mistaken impression that queer people weren’t around doing wacky, fabulous, transgressive things before we were. That’s mostly because these people are not very visible in mainstream history, but it’s also because even queer history tends to focus, understandably, on recent political struggles and prominent self-identified queers. It’s a pity, though, that we end up losing a sense of continuity with the past. I remember being ridiculously shocked and excited the first time I read about the Molly houses where eighteenth-century homos went carousing, or Captain Moonlite the queer bushranger (a real-life gay super-villain, cape and all¹), or the incredibly frank diary of Anne Lister. I never knew that queerness could be this real before the twentieth century.

I experienced an identical moment of delighted shock coming across A Narrative of the Life of Mrs Charlotte Charke for the first time. This little book, which was released in installments in 1755, is to my mind the progenitor of all funny queer blogs written in the first-person. Yes, this is the story of the first queer blogger. They were called Charlie. Actually, I don’t know if anyone called them Charlie, but I’ve adopted the nickname because it deepens my sense of unnatural intimacy across time and space. Charlie was born in London in 1713, the youngest child of Colley Cibber, an actor, theatre manager, playwright, and later Poet Laureate. Cibber the Scrubber is best known for writing terrible poetry and being lampooned as the chief dunce of England in Alexander Pope’s Dunciad, a satirical poem about second-rate writers. This would have been incredibly embarrassing, but, based on his behaviour to Charlie, I think Dunderhead deserved everything he got.

Charlie was female assigned at birth, and given the name Charlotte, but spent much of their life wearing men’s clothes and living under the name of Charles Brown. I use “they/them” pronouns for Charlie because, with the shifts they make between the Charles and Charlotte identities at various points in their life, it’s not really clear whether masculine or feminine pronouns are more appropriate. They have often been claimed by lesbian historians because of their involvement with a woman known as Mrs. Brown, but you can also read them as having a proto-trans* or genderqueer identity. Obviously Charlie lived in a different age, and would not have described themselves using these terms. Given the constraints of the time, they were never explicit about their reasons for presenting as they did. Still, it’s clear that they existed well outside contemporary gender norms, and that this was at the heart of their identity. The first story they relate about their life is a recollection of dressing in their father’s clothes at the age of 4. The style of this episode is typical of the memoir: it’s very funny, but also poignant. Charlie writes that, having always had “a passionate fondness for a periwig,” their little 4 year-old self decided to borrow Dunderhead’s wig and impersonate him.

Accordingly, I paddled downstairs, taking with me my shoes, stockings, and little dimity coat, which I artfully contrived to pin up, as well as I could, to supply the want of a pair of breeches. By the help of a long broom I took down a waistcoat of my brother’s, and an enormous bushy tie-wig of my father’s, which entirely enclosed my head and body, with the knots of the ties thumping my little heels as I marched along with a slow and solemn pace. The covert of hair in which I was concealed, with the weight of the monstrous belt and large silver-hilted sword, that I could scarce drag along, was a vast impediment to my procession: and what still added to the other inconveniences I laboured under, was whelming myself under one of my father’s large beaver hats, laden with lace as thick and as broad as a brickbat.

This is such a cute image. I imagine a wig with little legs promenading proudly down the hall. Charlie recollects being delighted by the crowd that gathered to watch, without realising that the spectators were laughing. It’s the retrospective adult understanding that they had become a figure of “shame and disgrace” that makes this a moving scene. Charlie also hints at the subsequent conflict with Dunderhead, who was indulgent on this occasion, but also ensured that Charlie was forced back into “proper habilments.”

Charlie married the violinist Richard Charke in 1730, at the age of 16. The passion of the match soon waned, particularly as Charke turned out to have “an unconquerable fondness for variety,” in the form of other lovers. The marriage did however give Charlie the independence to commence a career upon the stage, although this was briefly interrupted by the birth of their child, Catherine, known as Kitty. Charlie and Richard eventually parted ways, although he continued to visit when he needed money. Then he went to Jamaica and died, and I don’t think anybody cared. Certainly not Charlie, who was very successful in Dunderhead’s theatre, specialising in “breeches roles.” These were male roles which were usually played by women. There was nothing especially controversial there at the time.

But Charlie, daringly, took to wearing breeches offstage as well. Despite acting success, there were conflicts with the management of the theatre, which eventually led Charlie to leave. It was also around this time that Charlie fell out of favour with Dunderhead, having played a role parodying him in one of Henry Fieldings’ plays. The two were never reconciled. Charlie is characteristically evasive about the reasons for this estrangement, but as it all happened while they were moving toward wearing men’s clothes in everyday life, I’d guess that gender waywardness played a part. In 1737 the government closed down most of the theatres in London, and from this point on life was a financial struggle for Charlie. They tried their hand at a succession of jobs, including successfully running a puppet show for a while, but fell into debt and had to be bailed out by a group of women, coffee-house keepers and prostitutes, who were only too happy to help out young “sir Charles.”

I find Charlie’s glancing references to their full-time assumption of men’s clothes fascinating. It’s almost taken for granted, something not requiring comment, but at the same time they’re quite coy about it. The tone is similar all through the book. Charlie describes running out into the street in distress at the misapprehension that Kitty had died, and passersby being bewildered by this “young gentleman’s” show of distress for his child. There is also a hilarious passage in which Charlie describes an heiress who fell in love with Charles Brown, and had to be informed that her paramour was the youngest daughter of Mr Cibber. Charlie is seemingly open and matter-of-fact about these incidents, but never directly expresses their feelings about the situation, other than to point out how amusing it all is.

It’s this very tone that seems to me to link Charlie to the queer writers of today. Charlie describes the book as an attempt “to give some account of my unaccountable life.” They use humour to make plain, not only certain things that wouldn’t be acceptable if not framed as jokes, but also, by a sleight of hand, the pain of saying what you are not supposed to say, and wanting what you are not supposed to want. I think the best example of this is the early episode of wearing Dunderhead’s clothes, which Charlie frames as a joke, but which is clearly a deeply important moment for the child. Charlie is casual about the mockery and disapproval of the other people involved, but a lot of emotion is distilled into their selfparody. Another way of putting this is to say that Charlie is super talented at making painful incidents seem incredibly funny. Life never turns terribly cheerful for Charlie, but the story is always entertaining. After years of scraping a living at a variety of jobs, from strolling player, to sausage maker, to valet for the Earl of Anglesey, Charlie finally took up writing. The autobiography was a hit, but not sufficient to stave off poverty, and Charlie died penniless at the age of 42.

Dunderhead had died 3 years earlier, and left Charlie a tiny legacy of only 5 pounds, despite being rich as Methuselah. It should be pretty clear that I violently dislike the man, so I can’t contain my sense of glee about Charlie’s rumoured retaliation against him. Charlie recounts the rumour, ostensibly to refute it, but with such detail and relish that you can tell they enjoy the story too.

I hired a very fine bay gelding, and borrowed a pair of pistols, to encounter my father upon Epping forest… I stopped the chariot, presented a pistol to his breast, and used such terms as I am ashamed to insert; threatened to blow his brains out that moment if he did not deliver, upbraiding him for his cruelty in abandoning me to those distresses he knew I underwent, when he had it so amply in his power to relieve me: that since he would not use that power I would force him to a compliance, and was directly going to discharge upon him, but his tears prevented me, and asking my pardon for his ill-usage of me, gave me his purse with threescore guineas, and a promise to restore me to his family and love, on which I thanked him and rode off.

I love the way offhand way Charlie takes the money and dismisses the love.

Perhaps my favourite thing about the autobiography, though, is the preface. At a time when most writers included a preface explaining the work to the public, or dedicating it to a powerful patron, Charlie’s preface is entitled: “The Author to Herself.”

If, by your approbation, the world may be persuaded into a tolerable opinion of my labours, I shall, for the novelty-sake, venture for once to call you friend,—a name, I own, I never as yet have known you by.

That’s one of the most powerful things we take from queer history, I think: through telling stories, finding ways to be friends with ourselves.

If you’re interested in making friends with Charlie, A Narrative of the Life of Mrs Charlotte Charke is available online. Maureen Duffy apparently drew on the memoirs for her first openly lesbian novel, The Microcosm, published in 1966. There are a couple of biographies as well: Charlotte: Being a True Account of an Actress’s Flamboyant Adventures in Eighteenth-century London’s Wild and Wicked Theatrical World, by Kathryn Shevelow, and The Well Known Troublemaker: A Life of Charlotte Charke, by Fidelis Morgan.

¹ Captain Moonlite probably didn’t actually wear a cape.