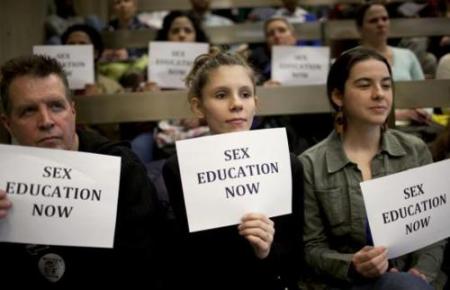

A coalition of groups concerned with health and education have released a new set of recommended guidelines for comprehensive sexual education in public schools, and while their ideas are still very much in the “recommended guidelines” stage rather than being reality, they’re still pretty revolutionary. Noting that current standards for sexual education are “inconsistent” and that studies have shown that sex ed in high school is often ineffective because students have already formed their own opinions, their recommendations call for “minimum standards that schools can use to formulate school curriculums for each age level.” For instance:

By the end of second grade, the guidelines say students should use the correct body part names for the male and female anatomy, and also understand that all living things reproduce and that all people have the right to not be touched if they don’t want to be. They also say young elementary school kids should be able to identity different kinds of family structures and explain why bullying and teasing are wrong… by the end of fifth grade, the guidelines say students should be able to define sexual harassment and abuse.

When they leave middle school, they should be able to differentiate between gender identity, gender expression and sexual orientation, according to the guidelines. And the say they should be able to explain why a rape victim is not at fault, know about bullying and dating violence and describe the signs and impacts of sexually transmitted diseases. It calls for those leaving eighth grade to also be able to evaluate the effectiveness of abstinence, condoms and other “safer sex methods” and know how emergency contraception works. Many of these issues the groups encouraged to be further addressed in high school as well.

One of the more remarkable things about these guidelines is that they’re designed to address bullying, especially as relates to sexual orientation and gender identity. There may not be a wealth of studies that prove it yet, but it seems entirely possible that a class full of kids who know the difference between gender identity, gender expression, and sexual orientation by the time they’re in ninth grade will be less likely to torment a classmate who wears eyeliner by calling him a “queer.” In general, education that addresses and explains difference in a nonjudgmental way seems like it will much better equip children to treat each other compassionately than an education which hopes that if it never mentions difference or diversity, no one will notice it’s there.

Of course, these guidelines have drawn criticism, and since they’re nonbinding and are ultimately only recommendations, schools which are committed to abstinence-only education or who refuse to acknowledge any problems with bullying probably won’t adopt them. Predictably, the executive director of the National Education Abstinence Association, has made a statement that “[controversial] topics are best reserved for conversations between parent and child, not in the classroom.” Many parents, and many school administrators, seem likely to agree with her.

The thing is, though, that none of the recommended minimum standards of knowledge seem particularly controversial. Is it controversial to tell a child that bullying and teasing are wrong, or that all people have the right to not be touched if they don’t want to be? Is it really controversial that gender identity and sexual orientation is different? I almost hesitate to ask because someone will inevitably agree, but is the idea that survivors of rape are not at fault for being raped really controversial?

It seems like what may actually be controversial about these guidelines is that they’re based on the premise that students are human beings who can be trusted to make choices. Although Valerie Huber of the National Education Abstinence Association said that “This should be a program about health, rather than agendas that have nothing to do with optimal sexual health decision-making,” that’s actually exactly what this is; educating children about their own bodies and the bodies of others, and the possible outcomes, both good and bad, of sexual activity — so that they can then go on to make their own decisions about what they do and don’t want to partake in.

Abstinence-only education operates on the idea that if kids are presented with only one choice, they’ll never make a “bad” one; never mind that studies have never shown that approach to actually work. Conservatives and homophobes use the same mistaken thinking about discussing gay issues in schools, arguing that inclusive education is “promoting” homosexuality — as if being kept in the dark about homosexuality would ensure that all students turned out straight. The point of these guidelines seems to be, more than anything else, about informing students to make their own choices, which is precisely what “optimal sexual health decision-making” requires. And for queer students, it’s an absolute necessity; how can you make optimal decisions about your sexual health if you’ve been taught that your sexuality doesn’t exist?

At the root of the new recommended guidelines for sex ed is the idea of treating students with respect, and believing that they deserve to know at least as much about their own bodies, sexuality, and sexual rights as they do about the Cold War. (And if students are queer or trans, deserve to know that they exist, and also have rights.) And regardless of how conservative you are or what “values” you care about for your children, there shouldn’t be anything controversial about that.