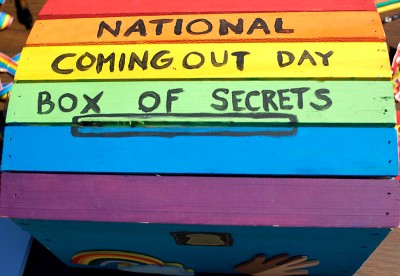

Today is National Coming Out Day: a day somewhere between a political statement and a celebration, with massively different meaning depending on how out you are or aren’t, to yourself or to others. It’s only been around since 1988, well after the political urgency around the AIDS crisis and queer militancy made the case that coming out was a political necessity for the queer community to be able to fight for its life.

The day contains in it the fundamental idea that if they know who we are, and if they know that they know us, maybe they will care about us staying alive. This was true and meaningful thirty years ago, when the fact that many AIDS victims were gay meant that the majority literally didn’t care if they lived or died. This is true now, when gay children are killing themselves and experts are scrambling to figure out why, and at the same time a (marginally) legitimate presidential candidate is tied to ex-gay therapy. Studies show that to know us, to know an out gay person in your life, is to care more about our issues. And more of us are out than ever. When National Coming Out Day was first created, Ellen DeGeneres wasn’t out yet; today, she’s married to her wife.

Do we still need something like NCOD? Does it mean something different now?

Well, coming out still isn’t safe for everyone, on NCOD or any other day. For some of us it means being homeless, being hurt, being exposed and vulnerable to violence instead of being honest. Pam’s House Blend says it best:

For some of us, including me, a transsexual Latino, a trans man of color, NCOD marks the beginning of a time of year when we are and feel particularly vulnerable, on the heels of the date marking the violent, fatal beating of Matthew Shepard, for whom, along with James Byrd, Jr., the anti Hate Crimes law, our country’s first fully inclusive anti-discrimination for sexual orientation and gender identity law, is named. and just ahead of the still-unsolved brutal murder of Rita Hester in 1998 in Massachusetts, whose death inspired Gwen Smith in San Francisco to create the International Transgender Day of Remembrance, recognized annually globally between Nov. 20 and 28 where my brother Ethan St. Pierre gives the somber gift of tallying each year’s murders of trans people globally… Yes, we have come a long way, but please use NCOD as an opportunity not to leave behind our most vulnerable.

It’s unsafe in other ways, too. Even if we’re out to our families, or even if we live in a state where ENDA protects our rights in the workplace, there’s no telling whether coming out at work might mean we don’t make the cut in the next round of layoffs. There’s no telling if our pastor will still support us in the way we need him to. There’s no telling if we would have still gotten pulled over for speeding if it weren’t for the rainbow bumper sticker. Regardless of how ‘out’ we are, we make dozens of tiny choices every day towards or away from telling people this specific truth about ourselves; no matter how much progress we’ve made, those choices still have consequences.

For some of us, coming out isn’t a matter of physical safety, and probably won’t result in anything as dramatic as parents disowning us or being fired from our jobs. But there are comforts and even fond, familiar discomforts in not living a lie, necessarily, but omitting a carefully chosen truth. Last week The Rumpus’s beloved columnist Dear Sugar answered a question about this very topic:

Whenever her parents come to town or call I feel like we’re having a secret affair. When I talk to her about this, she says it will get better and change, but she never shows me that she’s working on it… She grew up in a small town with a great deal of conservative church influence that her family is a part of. They aren’t a very emotional family and it seems they don’t have long, deep conversations about who they are in the world or who they’d like to be. But I’m not sure it’s those things. My girlfriend has difficulty articulating what exactly makes it hard to tell her parents that she’s gay. If I understood it was religious fears I could figure out how to be supportive with spiritual resources, if it was losing them then I could encourage her to look to role models… I don’t think she realizes how limiting this feels, even when we talk about it. She is upset that I’m sad about this, but she can’t bring herself to tell her parents that she’s gay… I suppose is my question to you, Sugar: How do you trust your love will be enough to ride out a gathering storm? What should I know? What would you do? How can I swim to the life we deserve? How can I save us both?

There are complicated reasons why we don’t always come out. Because everyone feels good when they feel normal, and that’s not always a privilege that openly gay people are afforded. Because even if the people we love won’t leave us, we love them enough that it’s hard to see them hurt, confused, or uncomfortable. Because straight people don’t have to come out, ever. Because we might not be out to ourselves. Because we might not have the words for what we want to come out as. Because it’s scary to feel like things are irreversible. Because sometimes it’s comforting to have at least a part of ourselves that belongs only to us, or to our most intimate inner circle.

The reasons that we finally do come out are maybe slightly less complicated. Because the relief of saying it out loud becomes more important than the fear. Because being in the closet is keeping you from living the life you want. Because it finally feels like the only thing to do. Or, like Sugar’s questioner, because someone who loves you needs you to bite the bullet. Sugar’s advice:

Last week I was in a hotel room flipping through the channels on the TV when I stopped on one long enough to hear a scientist say that a basic truth about human nature that’s found in just about every study and body of research is that people do what they want to do. The drive to do what we want to do is so strong that we will usually do it, even if there’s a price to pay. Your girlfriend can’t tell her parents that she’s gay because she doesn’t want to tell them that she’s gay, even if this makes you miserable. She wants to be in a loving lesbian relationship with you without allowing the other people who love her most deeply to know she’s a lesbian. This dual life allows her to have sexual and romantic relationships with women, while never having to announce to her parents that indeed she is the perverted, shameful, skanky freak that on some level she believes herself to be.

The question you need to answer for yourself, darling, is how long are you willing to stay in the perverted, shameful, skanky freak closet with her. It seems clear to me—and exceedingly healthy—that forever is not an option for you, so I suggest you have a serious talk with your partner about why this is so important to you and then together come up with a reasonable, loving, fair-to-both-of-you date by which you will leave her if she refuses to come out.

I don’t know that I agree — I don’t think internalized self-loathing is the only obvious answer to why this woman isn’t out. But I do think that while we once lived in a world where you had almost everything to lose by coming out and only the ideal of honesty to gain, for a lot of people, there are things — good things, beautiful things — that we can have only after coming out. Like families that we’re openly proud of, or the relationships with our parents that we’ve always dreamed of. And for a lot of other people, this isn’t true, and staying in the closet is a necessity. It’s a relatively recent development that we’ve had this choice; as recently as the 1950s, it was almost unthinkable. Now, it’s a decision that brings consequences, but is ours to make. And we got here on the backs of people who made that hard choice, and were honest about something unthinkable back when it seemed impossible to do. We — this website, this community, our queer friends and family — many of us are able to live the way we do and be however happy we manage to be because of the people who made that decision.

Whether you’re out, or not, or somewhere in between, today is a day to reflect on where you are in life; how far you’ve come in being able to tell the truth to yourself and to others, what kind of community you’ve been able to find. Maybe it’s none; maybe you’re one of the people for whom this isn’t an option. Maybe you just wore your OKAY TO BE GAY t-shirt to the local food co-op. Either way, we can think about what we can do and what action we can personally take to make sure that this is a choice everyone feels able to make. If you’re at a point where you feel you can tell the truth about your life, how can we help everyone get there? How can you tell your truth such that it makes it possible for someone else to tell theirs?

What does National Coming Out Day mean to you?

featuring image by Keith Haring