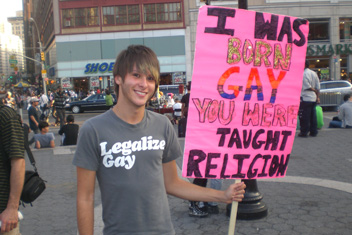

feature image via Born This Way

The “origin” of homosexuality is a topic someone somewhere always seems to be debating. Is it hormones? A “gay gene?” Environment in the womb? Early exposure to the X Files? With the exception of some outliers and scary conservatives who either believe or imply that we can be ‘fixed,’ it seems fairly well accepted that however we came to be this way, it wasn’t our choice. Well, Lindsay Miller is tired of talking about it. She’s tired of the campaign to amass evidence that we really were born this way in an effort to oppose haters and bigots. She doesn’t think she was.

“I would like to state for the record that I was not born this way. I have dated both men and women in the past, and when I’ve been with men, I never had to lie back and think of Megan Fox. I still notice attractive men on the street and on television. If I were terrified of the stigma associated with homosexuality, it would have been easy enough to date men exclusively and stay in the closet my whole life.

Obviously, no one sits down and makes a rational decision about who to fall in love with, but I get frustrated with the veiled condescension of straight people who believe that queers “can’t help it,” and thus should be treated with tolerance and pity. To say “I was born this way” is to apologize for the person I am and for whom I love. It’s like saying I would be different if I could. I wouldn’t.”

Well! The assertion that queers who believe they were born with same-sex attraction are being apologetic by doing so is perhaps a little broad. But overall, Miller’s points are as follows: being gay is actually great in a lot of ways, and it’s better to focus on them than hold up the homophobia and injustices we deal with to prove that being gay must be innate, because no one would want to deal with this.

It’s an interesting point — it’s hard to argue with the declaration that “Whether or not I deserve the same rights as straight people has nothing to do with whether I chose to be the way I am today.” And it’s true — there are amazing, wonderful things about being gay. We have an incredible community that’s often more supportive and caring than our biological families; we have a brave and bloody activist history to be fiercely proud of; our short fingernails make bowling easier. But none of that is what Miller is talking about — and I find the point she does make a little harder to agree with.

If there’s one thing to be said about lesbian relationships, it’s this: You always start from equal footing… Neither of us was raised with male privilege. Neither of us was raised to believe, on some subconscious level, that the way we perceive the world is the default setting, and everyone else is deviant.

If you’re talking about doing housework and childcare — which, for the most part, it seems like Miller is — then that might be true? Maybe? (Although anyone who has ever even lived with roommates of the same sex might argue that it doesn’t magically make the division of housework equitable.) But her underlying premise — that lesbian relationships “always start from equal footing” — seems pretty precarious. It’s great for Miller and her partner that “neither of [them] was raised to believe, on some subconscious level, that the way [they] perceive the world is the default setting, and everyone else is deviant.” Because that would mean that they are devoid of any kind of privilege whatsoever! At the risk of generalizing in the opposite direction: very few people, if any, “start from equal footing.” It’s true that two people can be of the same sex or gender, but that’s not at all the same thing. It’s great for Miller that she’s experienced her relationship as being free from the difficulty that major social difference and the difference in privilege that comes with it can bring. For people who are dating someone of a different race, size, sexual orientation, ethnicity, religion, class, education level, or income, that’s not necessarily something they can claim. It’s true that if they’re in a same-sex relationship they can share clothes and tampons and are less likely to earn 25% more at a similar job but not acknowledge the wage gap. But that’s a little bit of a different claim — Miller’s idea that we somehow get out of dealing with privilege and its baggage at all by being gay (or “choosing” to be so) seems a little overly ambitious.

And while Miller has a point, in that the “of course I didn’t choose to be gay, why would I want to face this much homophobia?” argument can have the unfortunate consequence of making being gay feel like a mark of Cain, her casual dismissal of it seems like another refusal to acknowledge privilege. It’s, again, wonderful for Miller that being gay hasn’t actually been holding her back. But for many people, the reality is bad enough that there isn’t really an option to de-emphasize this side of the story. If you’ve ever been made homeless and disowned by your parents, lost a job that you needed to survive, been threatened with or lived through violence and danger, survived suicide attempts or have friends who didn’t, or have almost killed yourself trying to change a part of you that you believe your faith requires you to but ultimately failing — well, if you’ve lived through any of those things, then “If I could choose, would I choose this?” becomes a pretty central question. It would be nice if we didn’t have to ask it. But until those things stop happening, can we afford not to?

It’s not that being gay isn’t great in a lot of ways. It’s getting better every day, as we win more legal rights and more social acceptance and visibility. And it’s possible, maybe even desirable, that the heated debate over how we came to be this way can be dialed down a little, that we can stop talking about the reason we’re gay as a way to defend our existence. It’s also possible, though, that the way to do this isn’t to play a game of one-upping with “normal,” straight relationships — to emphasize that we’d choose this “lifestyle” over theirs any day. To me, it seems like it’s not that we start off on equal footing and ‘they’ don’t; it’s that no one starts off equal at all. Sometimes we feel like we don’t even have our footing. We have that in common, gay and straight. But we work hard, and we come together anyways, from very different places, because that’s what love is, regardless of the genders of the people involved. And isn’t that actually why we choose the people and the lives that we do?

Comments

I know some of us feel we were born gay and some don’t, but as per the way I feel on a lot of issues, I wish we could stop trying to invalidate each other and acknowledge that there are people who fall into both camps. For me, finally stating “I’ve always been this way” was immediately freeing. Born this gay and proud of it, dammit. But that’s only speaking for myself. I support other queers who don’t think they were born gay because that’s fine too. Whether we were or not, there’s nothing wrong with being gay in the first place.

Explaining this concept doesn’t take that long either- “I was born this way, _____ was not, but we both ended up gay and that’s where we are now. Rainbow cake for everyone!”

I was formulating this exact comment in my head, basically.

Not only was I born bisexual (and knew as soon as I could formulate thoughts) but up until I was about twelve I assumed everybody was. The world was a pretty great place under that assumption, let me tell you. I had my first boy-crush, and first girl-crush in the same year and never differentiated the two. However, as someone who could choose to date men only, Miller is a very interesting woman to me. However people arrive at queerness is totally fine with me – I just hope that means that 12 year old me will get her delightful rainbow world eventually.

The idea of “any way you arrive at your gayness should be cool” is encouraging to me, but the rest of her theory is kind of privileged malarky. But I will say it was a revelatory day for me when I was told (indirectly, I think, at everyoneisgay.com) that it didn’t matter why you were gay, even if it’s a choice, you should be allowed to live the life you want to live. For a lot of us in that grey area between gay and straight, the label you infinitely settle on is the choice you make, I think (or at least it was for me). Like, I could say I’m bisexual, but I’d be denying the the fact that I only really see a female partner in my future. Are there still male outliers I’m attracted to? Definitely. But ultimately the struggle of NOT always feeling like I was born this way (because I spent a long time thinking I was straight) kind of makes me feel invalidated in my identity, so it helps to remind myself that even if it was 50% choice, that doesn’t make it any less legitimate. The problem with Miller’s theory is that there’s a difference between taking pride in your identity and doing so to the point where you delude yourself into thinking everyone is allowed to feel the same pride as you.

Amen, sista.

I totally agree with you. I think for people who are more toward the gay end of the sexuality spectrum it makes more sense to say ‘I was born this way’ and have that be the end of it. And maybe I was born with the propensity to be attracted to more than one sex and/or gender, but it’s definitely my choice to live in the queer community and actively seek a same-sex partner. So where does that leave me? I chose it but I didn’t at the same time.

This is exactly how I feel but I could never have put it down in words…

when i say i was born this way, i’m not apologizing, or saying i would change it if i could. i am saying that if i were not gay, i _would not be myself_. that would be some other person who is less awesome than i am. that is what i mean when i say i was born this way.

this is all of my feelings at once. Thanks for taking care of that for me.

any time :)

i was for sure born gay. ive known since i was about 6 i liked girls. so how is that explained any other way. its not like i thought at age 6 hey i might be gay my whole life just for the sake of it! i didnt even know what gay was til i was like 12 lol.

As a lesbian all I am interested is equal rights where laws protect me and my love one, if we choose to have kids that we both have equal rights. I think sometimes our community in trying to gain that equality we subject ourselves to too much over analyzing and too much separation, also with labels, I hate the word “queer” it makes me feel dirty. I know I was born gay and I also have been able to accept myself but I don’t feel I need to make an announcement, but I can understand why others do. As a minority you have to fight for everything and in today’s society that even means trying to explain to straight people that being gay is not a choice it is just who you are, it is just like a person being white, or black or a person being born female or male, the only thing we decide is how to come if to come out and when to. Ms Miller is a bi-sexual not lesbian so she does not speak for me, which I find is another issue because of the constant debates between lesbians and bisexuals it has confused the heterosexual society into believing that it is a choice and not how we are born, which is why for me I find that hollywood and even our own community has failed us in portraying lesbians and I think we ourselves are also responsible for the misconception.

I think the point that she’s missing here, and I haven’t read her entire article so maybe she includes it there, is that regardless of if every gay person was given $1,000 on their 25th birthdays or if we were loved the world over, that cannot prove or disprove the truth of being born gay. If she’s arguing that gay people only use that argument as a crutch, but still believes that it is possible that people are born gay, that’s fine. But that doesn’t seem to be what she’s saying. Instead, it seems like she’s implying that gay people choose to be gay, only clinging to the “born this way” label to make them more easily accepted by straight people. It’s fine to say that she feels like she choose to be gay, but “born this way” gays don’t choose this label just to be pitied.

No, I don’t think that is what she is saying.

She ends off with, “The “born this way” argument is frequently used in defense of gay rights, but whether or not I deserve the same rights as straight people has nothing to do with whether I chose to be the way I am. I deserve equal rights because I’m an equal. I’m a human being sharing my life with the person I love. The life I have now is not something I ended up with because I had no other options.”

I think she is saying that that whether or not she was “born this way” is irrelevant, she deserves equal rights regardless.

If only the headline wasn’t “Queer by Choice, Not by Chance: Against Being ‘Born This Way’”

Because this is at a major publication, the author probably didn’t make her own headline. That job would have fallen to one of their copy editors. This is generally because back in print journalism time, the headline length becomes dependent on the number of inches and columns allotted, so any headline that a writer prepared ahead of time would most likely be decimated in the editing process. For some reason this custom has carried over to major internet publications as well.

A good example of this is Carol Hanisch’s famous essay “The Personal is Political”- she has said she didn’t actually title it that way, the publication did, which is ironic since so many people attribute that quote to her yet it never appears in the text of her essay.

Anyways, blah blah blah THE MORE YOU KNOW!

Yes, what Ash says is true. Honestly I’ve never written for anyone who had me write my own headline, that’s always the editor’s choice — online or print.

As for why it’s still done, I think the headline sells the piece so even w/o the column inches, the editors know both SEO and overall what kind of title will entice readers moreso than any individual writer does. Our writers sometimes write headlines, but almost every headline you read is written by me, marni, rachel or laneia.

Never mind that she insults people who aren’t attracted to the opposite sex.

I read this and what I get out of it is people who didn’t choose to be gay are pathetic. She certainly chooses her words very carefully calling out “the gay rights movement” and straight people rather than gay people themselves, and I don’t think that’s by accident.

“when I’ve been with men, I never had to lie back and think of Megan Fox.”

Well good for her. Someone give her a medal for not having to cope with having sex with someone she didn’t want to.

A lot of gay people can’t have sexually functional relationships with the opposite sex. Some may not have even been born that way. Either way, it can be a greater source of agony for a gay person trying to figure out their sexuality than being attracted to the same sex.

It’s not that we don’t have any choice, but that the choice is between a sexually dysfunctional relationship and a functional one. Acknowledging that isn’t apologizing for it.

B-I-S-E-X-U-A-L

Gaaaawwwwd, it’s like everyone is soooo afraid of that word, like if they say it out loud they will be forced to kiss one boy for every girl, and the only marriage options open to them will be special three-person unions that not even Canada recognizes.

Okay, here is the form you need to fill out to join BISEXUAL CLUB:

1. Do you ever get turned on by boy-shaped beings?

2. Do you ever get turned on by girl-shaped beings?

Did you answer “yes” to both? Welcome to the club! The first rule of Bisexual Club, apparently, is DO NOT TALK ABOUT BISEXUAL CLUB.

):

P.S. Here is Miller’s original article in full: http://www.theatlantic.com/life/archive/2011/09/queer-by-choice-not-by-chance-against-being-born-this-way/244898/

P.P.S. Please join my club. There will be cupcakes and juice in plastic cups.

I try not to assign identities to people that they don’t use themselves, but seriously as I read

“I would like to state for the record that I was not born this way. I have dated both men and women in the past, and when I’ve been with men, I never had to lie back and think of Megan Fox. I still notice attractive men on the street and on television”

I was thinking, ‘gee this person sure sounds bi.’

I think she’s more saying that she used to be attracted to men, and now she’s not. (Except in passing on the street etc)

i.e. she wasn’t born gay, but now she is – which doesn’t necessitate that she chose to be that way, attractions can change over time

http://www.theatlantic.com/life/archive/2011/09/queer-by-choice-not-by-chance-against-being-born-this-way/244898/

This is what I take away from her article: “I am dating a woman, but not because I am exclusively attracted to women. I am dating a woman because I prefer women over men.”

I mean, at the beginning she goes out of her way to tell us how she could, right this very minute, be in a relationship with a man and it would be “easy enough”. That doesn’t sound very gay to me. And then she starts citing research about the supremacy of same-sex hanky-panky, as part of her “I chose this” argument.

I have no reason to doubt her experiences, which is why I don’t get why the word “bisexual” doesn’t appear once in her article.

If she’s chosen to date only women, I can see some kind of legitimacy in claiming the lesbian label, honestly.

That does make perfect sense from a practical standpoint.

Here’s another way to think about it: Imagine a person who experiences sexual attraction to other people yet identifies as “asexual” because of a vow of chastity.

I would say that imaginary person can self-identify however they want. Everyone gets to choose their own labels, or lack thereof. That’s the whole point–whether an asexual person feels they were born that way or that they made a choice, if they choose to identify as asexual then I would want to respect that identification and acknowledge them as such. I would also expect them to have full human rights because they are, you know, human. Likewise, whether a lesbian feels they were born that way or that they made a choice, if they choose to identify as gay then I’m gonna go ahead and respect that. Same deal with expecting full human rights. Why would that be an issue?

(For some reason it won’t let me reply to “V” above.)

I guess our point of disagreement is this: I believe words mean things.

(Oh I get it, we’ve hit the reply maximum!)

Please note that my shtick here is mosty an OCD-level obsession with nomenclature. If we were all part of a libertarian forum you might see me rambling about the true meaning of anarchism and it would result in a thread that was fifty pages long and everyone would realize at the end of the day we were all still libertarians even though nobody could say what libertarianism even meant.

I WILL JOIN YOUR CLUB

I do think that the queer world should be a little bit more inclusive to people who identify as bisexual. I am *very* slightly bisexual, but I would never label myself as that, because a) I don’t feel like that label is an accurate description of my sexuality, and b) I feel that some lesbians don’t take bisexual girls as seriously as they would a lesbian. I have known some girls even to say that they would outright not date a bisexual girl.

It’s like some people try to invalidate bisexuality. A lot of people just don’t believe in it full stop. Can we have a ‘you do you’ moment here? I just feel a little bit sorry for bisexual girls who, in my opinion, aren’t treated with the full respect they deserve.

Oh, and it should totally be allowed that people can have multiple person unions. I’ve always wondered whether something like that would ever work :)

Also, I will join any club where there are cupcakes :D

Yeeeeeah, I know what you mean about the dating thing. Ever since I came out as bi I’ve not been able to date any monosexuals. Which makes me sad. The only people who’ll give me the time of day (at least around these here parts) is bi guys and bi gals. I used to think being bisexual meant I had a huge dating pool, but that only really applies if I pretend I’m straight or gay as required. Which is like… marketing on a level I’m so not comfortable with.

I do have some straight-identifying friends who’ve admitted to very slight interest in the same sex, but I didn’t try to drag them into BISEXUAL CLUB. (I am nicer when I’m not on the internet.) I did have one straight-identifying friend who experienced euphoric same-sex sexaliciousness (including with yours truly) but continues to identify as straight because of…marriage? Something like, “I can only see myself being with…” I can’t even remember. (I blame societal and familial expectations, but try integrating that into sweat-slick pillow talk.) I wasn’t able to recruit that one into BISEXUAL CLUB even with cupcakes and sexmajik. Le sigh~

P.S. BISEXUAL CLUB is written always in all-caps.

Yeah, I really think this shunning of bisexuals from the gay community has a lot to do with heterosexual privilege. If someone is bi, they have the capacity to have opposite-sex partners, which we know places them at an advantage in society and makes things a bit, er, easier in that way. I think a lot of gay people are hesitant to date someone who’s bisexual because they are, even subconsciously, afraid that their partner would end up ditching them for the comforts of heteronormativity. Which, you know, is pretty tempting, in my opinion, when you’ve got so many people around you believing it’s the way things should be anyways. I’m sure plenty of us have had sour experiences with women who give us the time of day only to move on to men and deny their GAY FEELINGS. Ya know? This way of thinking is definitely harmful and dismissive of people’s experiences with their sexuality though…

Second to this is, of course, the fact that people still don’t want to accept bisexuality as valid. To them, you’re either gay or you’re straight, and “bisexuality” is just you being indecisive (so much eye-rolling). They absolutely refuse to believe that you can be open to both genders/sexes. It’s one of the things that really bugs me about how we’re expected to identify, because people would like you to declare one thing exclusively and fall into only one of two camps. So if you’re gay, then you’re ~*~GAY~*~ and there’s no possibility of dating the opposite-sex, ever, and vice versa with the rest.

What kind of juice?

I have a pretty big problem with the “born this way” mantra. Arguably, pedophiles were “born that way” too. Oh, and addicts. More broadly, I think the most science can tell us is that we are all born with a vast multitude of predispositions. But just because we are “born that way” doesn’t make it “good”. Using “born this way” to make a value statement about oneself is, imho, incredibly flawed.

So on the one hand, I can jive with Lindsay Miller when she says she’s sick of hearing it. And I agree with her when she says it suggests that we have something to “prove” – when I tell people I like pizza, do I only feel validated if I follow that with, “And I was born liking it!” No, because there’s -nothing wrong with liking pizza-. But I would go a step further and suggest that whether I was born liking pizza or not is pretty much completely irrelevant.

(But yes, a lot of what she’s saying is very throwback to ideas about sexuality that have long passed – the ‘equal footing’ argument is silly, for the reasons pointed out already, and the ‘I could choose men if I want to’ only works if you’re bisexual ;))

Pedophilia and addiction are pathological.

Gay right activists haven’t only been arguing that being gay is innate for the past several decades, but that it isn’t pathological. That was the whole point of getting it removed from the DSM in the 1970s.

Isn’t that circular though? Homosexuality isn’t pathological because it’s not wrong, it’s not not wrong because it’s not pathological.

Well, that’s the whole point about pathology, isn’t it? Pathology means something is wrong…if something isn’t wrong, it isn’t pathological.

No, something is deemed pathological if it has an adverse effect on a person or group of people–a disease or disorder.

Maybe you’re conflating “wrong” with “immoral” or maybe you just feel wrong. (And I think you need to reflect on the internalized oppression that implies.)

Pedophilia is pathological because it harms a group of people–children. Addiction is pathological because it harms the individual.

What is immoral is entirely subjective and not scientific. Something can be pathological but not immoral, like OCD or bipolar disorder. Mandy just happened to pick two examples that are generally considered immoral.

Homosexuality does not, in itself, adversely affect a person. But rather it’s the stigma and oppression that adversely affects gay people.

The point of the comment you originally implied to was that there exist things which are or may be inherent which are nevertheless wrong – ethically. Some people may be born alcoholics but that doesn’t make it OK for them to drink to excess, because it is harmful. You responded by saying that things which are inherent but harmful are different from things which are inherent but not harmful because they are pathological. This is a circular argument. Obviously the difference between something inherent and harmful and something inherent and harmless is that the first is harmful and the second is harmless.

I think we may be working at cross purposes. I’m not saying that there is anything wrong/harmful/pathological with same-sex attraction (obviously!) (there isn’t!) I’m saying that the fact that same-sex attraction is inherent in some people is not an argument for the fact that it isn’t wrong, harmful, or pathological.

(I hate using “not wrong” when I really mean “right”. I don’t like the effect of using double negatives here instead of positives when I really think that same-sex attraction is to be celebrated the same way we celebrate opposite-sex attraction. But I don’t think we can or should rely on biological determinism to support that.)

It’s a circular argument because you’re making it circular.

“You responded by saying that things which are inherent but harmful are different from things which are inherent but not harmful because they are pathological.”

That’s not what I said. And perhaps it’s because I’m being unclear. Pathology is the study of disease. What is a disease? Something inherently harmful as opposed to say being born with brown eyes. Why is cancer considered a disease? Obviously because it’s harmful.

My point, and I’ll make this a short as possible. The argument that homosexuality is an immutable trait (in some people) WAS NEVER THE WHOLE ARGUMENT. To suggest that it is the whole argument and argue against that is a straw man argument. It. Was. Never. The. Whole. Argument.

The ACTUAL argument is that homosexuality is 1) an immutable trait and 2) not a disease. It’s a two part, two pronged argument.

The ACTUAL argument is that homosexuality is 1) an immutable trait and 2) not a disease. It’s a two part, two pronged argument.

Yes, and my argument is that insisting on part 1 as a foundation for your argument undermines your whole argument.

And let’s be clear: I’m not speaking politically or religiously. I’m not talking about the rhetoric needed to decriminalise homosexuality in Tonga or to legislate for equality. I understand why the born this way narrative is important in that debate.

But. If tomorrow someone came up to you and said, hey! Here’s a Heterosexuality Pill! Refusing to take it (if you did) would be choosing your sexuality. And even if you did that, *marriage equality would still be important*, and *decriminalising homosexuality in Tonga would still be important*. Doesn’t it piss you off when people go through anti-gay camps and come out the other end “straight”? And then that’s used as an argument against who you are and it comes down to a big argument of he said, she said? It pisses me right the hell off, because at the end of the day *I don’t care what he said or she said* or whether it’s a choice for some people. Because that’s not the point and it shouldn’t be the argument.

Maybe it shouldn’t be, but it’s what’s worked. If arguing that for some people it is not a choice results in greater freedom for people for whom it is a choice, I don’t see what the problem is. I’m not making a principled argument. This isn’t an ideal world. If it were we wouldn’t have to argue for equality in the first place.

What pisses me off is people going through the anti-gay camps coming out the other end fucked up. One successfully ex-gay person doesn’t justify the many who are harmed by reparative therapy.

What pisses me off is the use of eugenics to try and eradicate homosexuality from society. What pisses me off is that the initial public response to the AIDS crisis was “If you don’t want to get AIDS, don’t have gay sex.”

The existence of people for whom it isn’t a choice is enough that no one should be forced to choose between heterosexuality and torture/prison/death. I don’t believe the existence of people for whom it is a choice undermines this argument.

It’s not that we want to be accepted because we were “born this way,” it’s that some people are convinced choose to be gay, and resent us for it. For instance, these little shits on Facebook http://imgur.com/hdbn8

Or John Cummins, the leader of British Columbia’s Conservative Party, who told a radio interviewer that gay people shouldn’t be covered by the BC Human Rights Act because being gay is “a conscious choice.”

It’s not that being born gay somehow “justifies” our gayness, it’s that the myth that we *aren’t* born gay is willfully spread to justify hatred and violence.

@the link: i can’t believe this! I feel lucky for not having had to face those kinds of idiots. :/

Well, fuck the haters. Why can’t we disprove their claim that just because some people choose queerness, it’s not legitimate?

“If I were terrified of the stigma associated with homosexuality, it would have been easy enough to date men exclusively and stay in the closet my whole life.”

Check. Your. Privilege.

The stigma isn’t as bad as it used to be because of those who had no choice. And there are still many who are terrified of the stigma.

You’re absolutely right about people being terrified of the stigma. A friend of mine came out of the closet, told her parents she was dating a girl, and then 2 months later told them she broke up with her because of all the crap she was getting. They’ve been together for over a year and my friend’s mom still calls her once a week asking if she’s found a boyfriend yet. She’s still ashamed to go out with a girl in public, because she doesn’t want to appear gay.

My main problem with her article is that it’s not like she asked anyone else if they felt like they were born gay. Maybe she’s lucky enough to have a choice. I’m not.

“It’s, again, wonderful for Miller that being gay hasn’t actually been holding her back. But for many people, the reality is bad enough that there isn’t really an option to de-emphasize this side of the story. If you’ve ever been made homeless and disowned by your parents, lost a job that you needed to survive, been threatened with or lived through violence and danger, survived suicide attempts or have friends who didn’t, or have almost killed yourself trying to change a part of you that you believe your faith requires you to but ultimately failing — well, if you’ve lived through any of those things, then “If I could choose, would I choose this?” becomes a pretty central question.”

Thank you so much, Rachel, for cutting through the privileged bullshit so succinctly. I can’t begin to describe why articles like this woman’s stress me out so much–I feel like I’m being tacitly judged having gone through a period in my life when I very much wanted to be anything-but-gay thanks to my conservative Christian childhood. Having gone through that trial by fire, I don’t for a minute regret being able to say confidently that I am this way and I can’t change it. I deserve equal rights regardless, but this is something I know about myself that I learned through years of blood and tears–it hurts to see someone dismiss it so blithely.

So much this.

I really don’t think she’s trying to devalue anyone else’s experience. I think what she’s trying to do is reopen the general discourse surrounding “The American Gay Experience” which so often becomes just one story.

I really, really agreed with this article, because so often the mainstream media and the general public get the message that all gay people feel the same way about their gayness – ie that they:

1. were born gay from day one

2. want to get married and have kids and a dog and a white picket fence

3. want to join the army

4. are just like straight people except for one tiny difference

These are the politically correct things to believe about gay people. But while many people do identify with some or all of these things, many people do not, and I think those people get lost in the discourse. We’ve sacrificed a lot of the queer edgy diversity of the earlier movements in order to make ourselves more palatable to middle America. This may earn us the right to marry and join the military, but it also isolates and alienates whole swaths of the population – those people who would rather break down the institutions of marriage and the military, those people who would rather form new kinds of families, and those people who believe that actually we’re NOT just the same as straight people – we’re different in a lot of awesome, beautiful ways.

This resonated with me on so many levels. I encourage people to read the whole article before forming opinions.

I agree with this–I feel like the whole “born this way” discourse just perpetuates the gay/straight, male/female binaries, and the whole point of the queer movement not so long ago was to break down these binaries and let everybody just love who they love and not make such a big effing deal about it.

when i say that i don’t think anyone is 100% gay or straight, and that sexuality is not fixed but fluid, and can change over your lifetime, i’m not trying to invalidate all of the struggles that my fellow queers have gone through because of who they think is hot. i’m just talking about my beliefs on the nature of sexuality. and since, as we’ve all been saying, no one has “proved” anything about the nature of sexuality, then all of you telling lindsay that she probably was born that way are doing the exact same thing as the homophobes who are telling us that we can be cured. who cares WHY we like who we like. let’s just agree that we will all fight for the right to do so without being beaten up, fired from our jobs, etc.

YES. I agree with both of you. Gay people being “born this way” often ignores our social environment, and reinforces certain structures (reminds me of the discourse about multiculturalism). I think this is what bothers me the most about it. All it does is concede that homosexuality is a real thing, but doesn’t really question how our political, national and social upbringings are a part of it. I hate to see it usually only amount to homonormative ideas too. Until people can accept sexuality as a deeply complex and often fluid thing, until they don’t want to peg people as biologically hetero or homo, I don’t think we’ll ever find full acceptance and openness to different sexualities/lifetstyles.

We’ve got a long ways to go…

I like Miller’s overall point- we have nothing to apologize for and nothing to blame for who we love, cuz our love is fucken rad. It is true, also, that some folks in the Queer community have experienced a sense of choice, and ultimately made what what they felt were educated decisions. I read a study on lesbian Femmes several years ago that describes my own coming out experience, as well as several of my friends. I was so excited to find that I wasn’t alone in my feelings and history!

I don’t think this is meant to discount those who have always known. Instead, I think these points are being put forth as a way to illustrate the different paths that lead us to identify ourselves and live as we do, which are ALL valid.

Lots of fascinating pieces have been written on the larger conflicts between biological existentialists and cultural constructionists, including the implications these perspectives have for how we all view sexuality, sex n gender, race, etc. I found one such article from Off Our Backs- “Biology, My Ass”. I recommend it, with the caution that it may piss some readers off. Also, I’ve lost the link to that study on Femme lesbians since I quit the college education stuff, but if anyone would like it perhaps I can dredge it back up!

On my best day I can nail my identity down to pansexual, but even that causes me a headache so I tend to just go with queer. To that end, the whole “I was born this way”/biological basis for sexuality camp has always made me a bit uncomfortable, as to me it doesn’t seem inclusive to my more fluid sexuality. Somehow “I was born this way” and “Well lately I’ve been feeling like a 4.5 on the Kinsey scale, but I range from 2 to 5” have never really meshed for me, which makes a lot of political arguments uncomfortable :/

I know that bisexuals like to claim that we’re all part of this “big happy family” where even bi’s can be gay. But it’s times like this where we’re reminded that bisexuality and homosexuality are not the same fucking thing.

And it really pisses me off when bisexuals pretend that it IS the same fucking thing and they throw words around like “choice” and “wasn’t born this way” and pretend that it’s just FINE to apply this to the “American Gay Experience.”

No, sorry. Maybe to you that’s the American Bisexual Experience. I’m not saying it is. But I am saying that it’s most definitely NOT the American Gay Experience. That much I know.

Thanks.

Though there are bisexual people that identify with the “born this way” thing, as evidenced by dappled’s earlier comment. And perhaps there are gay people that do not identify with “born this way.”

I think it is a bit of a bisexual, gay difference.

Considering bisexual people could very well choose to exclusively date people of the opposite sex (and still be dating people they find attractive).

Even more so, I could see “born this way” not working for anyone that has experienced their sexuality as fluid as opposed to fixed.

“Considering bisexual people could very well choose to exclusively date people of the opposite sex (and still be dating people they find attractive).”

Everyone keeps saying this, and every time I kind of think, “What the heck?”

Being bi doesn’t mean you’re not going to fall in love with a girl and want to be with her, just because you have the option of falling in love with a guy. Are we saying that bisexuals also have complete control over who they have chemistry with/feelings for?

I dunno, I just feel like this argument reduces romantic relationships to grocery shopping. Like, “Well, I like Kraft AND Velveeta, but the Velveeta is on sale today, so I’ll buy that one.”

Yes, thank you for saying what I think/feel every time!

Your analogy comparing cheese to true love is so perfect and holy that it is blowing my mind

I dunno, I have known some bisexuals who prefer one gender for romance and the other just for sex (and wouldn’t even consider them for a relationship). I’d definitely say that’s a conscious choice.

No, I am not saying you can control who you have feelings for. But you do choose who you date.

I don’t know, personally, it is something I think I could do, it is just something I wouldn’t want to do.

The point I was getting at was more along the lines of what Tui said, “if what determines that women having sex with women is OK is the fact that some people are only attracted to women, doesn’t that kind of imply that bisexual people are obligated to practise heterosexuality since, you know, we *can*?”

You know, excluding someone from the gay community hurts just as much for bi people as it does to be excluded from the straight community. I don’t see how excluding people and dividing the community helps anyone, and it especially sucks to see it on here :/

I kind of want to turn this around on you. Maybe this is my bisexual privilege speaking, but if what determines that women having sex with women is OK is the fact that some people are only attracted to women, doesn’t that kind of imply that bisexual people are obligated to practise heterosexuality since, you know, we *can*? And that if I want to marry a woman it’s not as important that I have the right to do so because I wasn’t born wanting to marry her, I can just go and marry a man.

I don’t agree with her implying, as if it were universal, that sexuality is a choice. But I don’t think that what makes women having sex with, being in love with, dating, living with, having children with, marrying, or breaking up with other women OK, good, right or natural, is the fact that lesbians exist.

This is loaded with so much privilege it makes me sick, jk jk I love you like a homogay loves unicorns!

aka..

I agree.

this is the nicest thing anyone ever said to me.

No problem, I had an intimate connection to your comment so I just felt I had to say something to let you know. I enjoyed it, I hope it was good for you as it was for me, it was consensual and do it again.

This. Agreed, Orko. I can’t believe the word bisexual isn’t even used once. This Lindsay Miller person needs to get a little more self aware, or maybe just get out more and learn what bisexuality is.

At first, that was my reaction, but then I thought, who am I to decide what this other human being NEEDS to do/think?

Maybe this person chooses to go label-free?

Another argument for the “born this way”/innate stream of thinking is that in the US, for sexual orientation to have a chance of being included as a suspect (protected) class under the equal protection clause, the trait has to be immutable.

Which is interesting, considering one of the protections we hold most dear is freedom from religious persecution.

I really just think “freedom to have sexy times with whoever you want as long as it’s legal, sane, safe, and consensual” should just be written into the Constitution. With glitter pen, if possible.

I would just like to point out that although many of her comments may seem to indicate bi/pan sexuality (including: “If I were terrified of the stigma associated with homosexuality, it would have been easy enough to date men exclusively and stay in the closet my whole life.”), many bi / pan / queer girls (myself among them) would not find this statement to be true in their own lives at all, especially those who do feel like regardless of whether they were BORN this way, there’s not much they can to do change it, even if they wanted to.

Personally, I found the closet to be very emotionally, mentally, and psychologically restricting and damaging, and can’t dream of going back in, regardless of how much I like girls or boys or otherwise-identified sexy people, respectively.

Gagh, tired commenter is tired; apologies for any incoherency.

..it’s that no one starts off equal at all. Sometimes we feel like we don’t even have our footing. We have that in common, gay and straight. But we work hard, and we come together anyways, from very different places, because that’s what love is, regardless of the genders of the people involved. And isn’t that actually why we choose the people and the lives that we do?”

This is what I feel 100%, oh yes.

Since my “Born This Way” blog is linked right at the top, I kinda feel the need to chime in here.

IMHO, declaring we are born gay is in no way an apology about it. Or means we want pity, or we want to change our sexuality. Nope, it is simply factual information about us. And it’s actually a factual statement on HUMAN sexuality.

HOWEVER, there’s still plenty of people who think/believe that we had some kind of “choice” in our sexuality. So the more we can disprove this, simply by STATING that fact, the better off we will be.

And, when the day finally comes when human rights are NOT based on who we sleep with, then maybe we won’t need to keep saying it. So…..

Congratulations, Lindsay – you’re a bisexual!

And guess what: You were probably born that way – unless you somehow chose to try something different at some point?

Telling people how they should identify is quite condescending. There are plenty of people, as you say, that identify as lesbian, bi, gay, queer that DO feel they have had a certain amount of choice- maybe better called agency- in how they identify. There’s a difference between sexual orientation and sexual preference.

“It’s true that if they’re in a same-sex relationship they can share clothes and tampons and are less likely to earn 25% more at a similar job but not acknowledge the wage gap.”

Just because it’s going around tumblr and I’m therefore hyperaware of it: The wage gap (in the US, I think) between white women and black men is bigger than the wage gap between men in general and women in general. So like. yeah.

Meh. I’ve never been a fan of the “born this way” discourse that tries so hard to prove some sort of biological cause to one’s sexuality. It simply dismisses a lot of people’s experiences. I, for one, don’t think it applies much to how I came to understand my sexuality. At all. Feels too much like trying to reduce an insanely complex issue to one simplified principle.

Personally, I have a much more complicated relationship with sexuality. I think everyone has the biological capacity to be attracted to anyone. However, I think our experiences, from the moment we’re born, have the powerful ability to shape who we are, who we like and what we want in life, some of these manifesting themselves in the early years of our lives. In this way, I don’t think sexuality is a choice that we have control over (although for some people it really is). But I also don’t think it’s something that wasn’t molded just like nearly every other aspect of us. Unfortunately, so many possibilities and our relationships with other people are stunted by a social system that controls how things are presented to us, and tries to tell us exactly how we should live. I really think if this weren’t the case, sexuality wouldn’t even be a thing and we could just love/bone whoever we wanted with no worries of sex or gender.

But, as it is, “men” and “women” (as people have loved to frame it) are very different in the world we live in right now. I don’t believe there exists any body that isn’t marked or without cultural signs, no matter how you identify, which seems to influence our sexualities and relationships to gender/sex. The way we understand the genders is so divided that even the very basic pieces of our relationships with others are forever altered. So I can understand what she means when she says that two women start off at an equal footing because, in some ways, this is true (although, as it’s been said, we never truly start off at an equal footing in the most purest sense). This is actually one of the things that draws me in towards other women. For me, I know it’s very much a product of my social environment. I go in expecting less of that strange, gendered power dynamic and male privilege. I find it’s easier; it feels more “natural.” It’s exactly what keeps me from finding men sexually attractive and desirable. Also, I hate men. So. (Kidding! Mostly).

Regardless of how many people identify as homosexual/bisexual/pansexual/etc. or how they came to this understanding, I wish there wasn’t such a pull to find a source. I’d rather like to accept it as another part of life. Let people love and be physical with who they want, and give up the forced classifications.

I think what she means by “equal footing” in same-sex relationships is that you can wear and apron and cook a steak for your partner and not feel like June Clever. You can just do nice shit for your partner and not think about patriarchy when you do it. At least that’s what I like about being with girls (among other things, including the girl parts).

Her whole point is that hopefully the way we think about queer is evolving from the excuse of “we can’t help it” to “If I could help it, I WOULDN’T” to not being a thing that needs explaining at all.

I can but applaud…

The problem really is that you can say anything, but you probably were “born this way”. You don’t see straight people claiming they weren’t born straight do you? Yes, there’s probably other factors. For example a bisexual female (cis or trans*) might be more attracted to women overall because of a bad experience with a male. That could perhaps be defined as choice, but it seems odd to me that anyone would sit up one day and just decide on something that innate.

Yes you can decide on a label, (I tend to go for queer myself, for reasons too long to go into here) but you don’t really decide your sexual preferences, that just sort of happens. At least in my opinion.

>>but it seems odd to me that anyone would sit up one day and just decide on something that innate.>>

But that’s the thing – perhaps that isn’t how other people experience it.

I remember citing all those researches done on how homosexuality is related to gene and all, after which my homophobic(I don’t ever speak to her about gay things, she knows that I’m gay, but it’s sort of brushed under the gigantic rainbow rug, she thinks it’s an illness of sorts) mother chastised how my married closeted gay uncle was caught cheating with numerous men, and had sexually harassed a man.

Which is ironic now that I think about it, seeing how I, his related niece, have had the occasion during which it was necessary to lie back and think about Megan Fox. But yeah, I do need all those ‘born this gay’ ammo. I do realize that it could be a double edged sword but it’s definitely doing more good than harm. I was born this way means that this is who I am. It isn’t a reason, nor should it be apologetic, it’s a simple statement. I am born straight. I am born queer. I am born with a weird eye. I am born ‘me’.

WTF happened to my grammar?! *was*was*was*was

Somehow I feel less gay right now.

Clearly there are a lot of feelings about this. Me? I believe that I am the sum of my physiology and my experiences. I won’t apologise for that.

I love who I love, I have sex with whoever the fuck I want. It’s got nothing to do with my friends, my parents, my coworkers or anyone else. I choose to be open with my life because I want to share it with them. It doesn’t mean that it’s any of their damn business (or society as a whole), and I definitely don’t deserve any fewer rights because of who I choose to kiss goodnight.

As I have said before, people are far more willing to accept someone who are helpless in a situation than someone who chooses it. That is a simple fact. Maybe you think gay people should be accepted whether they choose it or not — that’s fine, but it’s not reality. If someone is born with a problem that makes them unable to walk fast, you’ll be a lot more OK with waiting for them than if they just walk super slow for the hell of it. It’s such a simple thing to understand that it blows my mind some people don’t get it. If the goal is acceptance, the “born this way” mantra is a very powerful tool. (And furthermore, I was born this way. Every gay person I know was born this way. And I have a problem with people who are in all likelihood bisexual saying they chose to be gay, knowing how confusing and harmful it is to the gay rights movement.)

I think we should aim for more than just acceptance. I really believe we have something to offer, something to bring to the table – that we are adding something to society rather than just assimilating into it. Our queerness gives us a new, valuable perspective, and I’m interested in dismantling the traditional perspectives surrounding sex, gender, and sexual orientation.

I don’t believe I was born gay, simply because as an baby I was primarily attracted to cookies and stuffed animals. All the many things I would go on to do and be were possibilities, but not necessarily fixed. For the record, I don’t believe infants are really born heterosexual, either. This is not the same as saying I chose to be gay – just that it’s a complicated and mysterious thing. (However, please know that I’m not trying to devalue or undermine anyone else’s perspective, and that I whole-heartedly support everyone’s right to identify however they wish).

People are complicated, and they’ve been embracing/outlawing/tolerating homosexuality for a really long time, with wide-ranging results. It’s only very recently that we see “gay” as an identity rather than a behavior. Furthermore, the existence of genderqueer people really throws a wrench into the gay/straight binary. I identify pretty strongly as a lesbian, but I think androgynous genderqueer people are SO FINE. and i don’t need to call them ladies in order to find them hot. And I don’t think I was born with a genetic attraction to people with alternative haircuts, converse shoes, and carhaarts. Although, honestly, those would be some pretty awesome genes.

I disagree. What more should we want than acceptance? To be celebrated and praised? For what, being gay? Acceptance is something that occurs when you take someone for who he or she is. Acceptance is simple respect as a human being. Any celebration is earned individually, in my opinion. If gay people are going to be revered as some huge benefit to society, that is something gay people will need to earn one by one. We aren’t even accepted yet. You can’t run before you walk. I see acceptance as a perfectly valid, worthy and especially achievable goal. I think you missed my point entirely.

As for a gay gene, I’ve read some really interesting stuff. They haven’t located the so-called gay gene yet. But the basic question emerges: Why would there be a gay gene at all? Wouldn’t evolution get rid of it? Especially since gay people have far fewer kids and definitely not as couples? Well, some scientists speculate the genes responsible for sexual orientation are similar to the genes for sickle-cell anemia: If you have a sickle-cell gene from mom and a sickle-cell gene from dad, then you will get sickle-cell anemia, a deadly disease. But the sickle-cell gene remains a part of the population because, if you only have one of them you will be resistant to malaria, a benefit. The thing is, people’s sexuality can be affected after they are born. People who experience sexual abuse, for example, can struggle for years with their sexuality, and in more ways than just orientation. There is a psychological component to sexual behavior. Separating that from the biological orientation is very complicated. I’m just hoping they find that gay gene some day (soon). Then we could test Marcus Bachmann!

1) It probably isn’t linked to one single gene because those traits are incredibly rare. Plus, it would make more sense in the degrees of sexuality existing in the world.

2) I actually remember reading awhile ago that bisexuality (yes, I know, cringe at the word!) could have been advantageous for females prehistorically. Apparently, the ability to pair-bond with another female was advantageous when the males would die sooner. So, two mommies raising kids is better than a single mom. I don’t think this really makes that much sense if you look at, oh, you know, everyone else on the queer spectrum, but it was a neat theory in that it was looking for a positive spin.

I don’t really like to say “i was just born this way” either, it smacks of the apologetic or even an excuse. I think we should stop saying it because quite frankly we shouldn’t have to. its irrelevant why we are gay, lesbian, queer, bi. the fact is that we are and you know what? it ain’t changing no matter what they think or say.

Oh boy, you guys. I am feeling A LOT of feelings for a bright autumn Friday a.m. after reading this piece and all the comments.

Chief among those feelings: perplexity. For one, perplexed because there is no link to the original piece in all this article? Really? Not even a mention of the publication that ran the original piece? Hey, @internrachel (did I do that right…) can this be edited to include that information? I did finally find the original piece, thanks to the commenter who mentioned the title. Googling “Lindsay Miller” didn’t get me anywhere.

I’m also perplexed that according to many a commenter here, Ms. Miller and those with similar experiences (hi! Like me! Right here!) are “hurting the movement” and being dishonest and participating in some kind of auto-bi-erasure and hijacking the REALGAY community and I dunno what-all else because of how we choose to identify. It feels super shitty! I dunno, thought you all might like to know how it feels. Just a heads up.

For almost a year now I’ve been wanting to write some epically epic essay about my sexuality and my identification and every everything ever, and I haven’t yet and I don’t think I’m gonna accomplish it in this here comment box, but I guess the short version is, don’t you dare tell me what word I am allowed to use to describe my experience and I will extend the same courtesy to you.

If I call myself gay it’s because that’s the word that fits best. Period. You’re just gonna have to trust me on this one. And trust me that I will fight to the death for the rights of my born-this-gay peers, but humbly request a seat at the table when the day of fighting is done, along with a respectful acknowledgment that we have traveled different paths to our shared table and that this fact is a-o-fucking-kay.

That’s all.

Is it okay if *I* call you bisexual and not gay?

There doesn’t seem to be one accepted definition of this word and I’ve found it problematic. Like it’s use, or lack of, makes people feel shitty.

In my vocabulary, gay=homosexual. I realize it’s different for you, and others.

I want you sitting at the table when the day of fighting is done. We can have a slice of pie and talk about our different paths and what makes us happy.

[Heyyyyyyy @newtexan ! Just prefacing this with an @-mention here in the hopes that it means you’ll be notified of this comment. AUTOSTRADDLE WHY IS THERE STILL NO COMMENT REPLY NOTIFICATION JUST WONDERING]

No, actually, it’s not okay for you to call me by a name I no longer identify with.

I understand your frustration about the many interpretations of words like bisexual and gay and homosexual and on and on. I would suggest that language on the whole is a fragile and unstable system. For the most part, language can only gesture at meaning. It doesn’t possess meaning in any stable way.

However, I would also suggest that the times when the usage of such words results in shitty feelings are really only when someone feels their own identity/identification is being disputed by the way someone else is using those words. You know? It’s just not gonna end well, feelings-wise, for someone to disregard another person’s sovereign choice in self-identification and say “Well, you can call yourself X, but *I* think by X you mean Y and that’s what I’m calling you.”

That said, I’ve got no problem (and no business protesting) if someone calls me “gay” and mentally adds “…but in a way that feels more like bisexual, by my own understanding of those words,” or perhaps “but in a way that is very different from the kind of ‘gay’ I am,” if it makes them feel better about having to apply “gay” to someone with a not-so-static personal romantic-sexual history.

But in conclusion: bisexual does not describe my present reality any more than 4’5″ describes my present height. Those both describe a very real reality, but from the past. And while gay and 5’7″ may still only be approximations, they’re closer than anything else these days.

THE END. NOW FOR PIE. (Man I really wish I actually had pie right now.)

All the emerging biphobia on this thread is making me sad :( So some points:

1) A bisexual person saying something that you find dickish isn’t an invitation to bitch about all bi people. Just like every time a lesbian does something bad we don’t talk about its a larger indication of how shitty all lesbians are. I’m really sad to be seeing a lot of this here. Considering the wide amount of variation within any label (lesbian, bi, queer, etc etc) making sweeping judgments about the people of any label seems silly.

2) While she has dated men and women or used to date men or once fell in love with Johnny Depp’s smile or whatever, we don’t get to label her. While a bisexual label may seem appropriate for her or lesbian may seem legit since she’s no longer dating boys or blah blah blah we don’t get to assign labels for other people. We should also not try to police those labels.

3) Not all gay people feel they were born this way, not all bi/pan/queer people feel they chose it, and that’s all fine. Deviating from the standard born this way argument isn’t “harmful… to the gay rights movement” as I worryingly saw up there. We are people first, not parts of a political movement. None of us are responsible for upholding “the cause” 24/7

4) Think before you speak (write, whatevs). That goes for everyone. The LBGTQWTFBBQ community includes a lot of people with a lot of feelings, and rather than working to invalidate some peoples experiences we should work to have a better understanding of them.

5) Let’s all be friends! Please? I have ice cream

I WILL BE YOUR FRIEND and bring pie to share with your ice cream. Thanks for this comment. I feel a lot better after reading it. FEELINGS.

PIE omg I love you

re #2: I think people’s problem is with how she’s using her own experiences (that read as bi to others) to argue that being gay is a choice for all gaymos. If she’d chosen to label herself as bisexual, or at least “formerly straight all out lesbian” or something, it wouldn’t come across as awful and insulting as it has. Her stupid generalizations would still be stupid, but then she wouldn’t be smacking obviously queer people who can’t be any other way with “being gay’s awesome, I could’ve been straight but chose differently”. It’s hurtful to bisexuals too. Being attracted to men and women doesn’t mean liking them equally or wanting to have relationships and/or sex with both the same way.

“Being attracted to men and women doesn’t mean liking them equally or wanting to have relationships and/or sex with both the same way.”

I’m kind of confused about this, because that is exactly my experience. When I am attracted to a woman it does not feel different than how I feel attracted to a man. So please don’t assume that your experience is a substitute for everyone else’s. I also don’t see how this has to do with the problem at hand?

My experience too.

Which people have all kinds of problems with! They just don’t understand that I can feel the same about men as I do about women, tough to explain to them other than saying I just do!

“Neither of us was raised to believe, on some subconscious level, that the way we perceive the world is the default setting, and everyone else is deviant. ”

Perhaps not in the mind of male privelege, ok. But if she is white, middle-class, college educated, able-bodied, thin, has English as her first language in the US, the list goes on, then she does just that, all the time. That’s a pretty bold statement to make.

Yeah, I thought the same thing.

Also, w/r/t to the many partially or entirely biphobic comments above (see Ash above for some more points):

Implying that for ALL people who are bi / pan / queer-in-a-non-monosexual-fashion, choosing/being forced to choose to express attraction/desire/feelings about only one gender (out of so many incredible options!) would be no big deal is INCORRECT.

For MANY of us (who knows if it’s most or not, but that part isn’t actually important, duh), that would be a big fucking deal. I like girls and I like boys and I like genderqueer folks, etc. and I am ONE HUNDRED PERCENT (100%) QUEER, and no one gets to take that away from me. And it is NOT OK to tell me I’m not, or that you know more than I do just how queer I am.

Likewise, even though I (a girl) would theoretically be able to only ever date boys, if this happened via a conscious pressured choice to fit some mould rather than coincidence or some-non-coercive-choice-situation, although the sex, etc., might be more fun than for someone who ID’s as a lesbian, the pain of not being to express who I am, of having to hide such a huge part of myself (not just ‘liking girls’, but my whole darn sexuality) would be, for me, UNBEARABLE.

Furthermore: WTF is with all this ‘bisexual privilege’ nonsense! It’s not a frackin’ privilege to have all sorts (read: staight, and not straight) of people to assume you’re only attracted to people of the gender you happen to be in a relationship with at the time. It’s not a privilege to be told outright and otherwise (see many times in this comment thread for instance) that you just aren’t queer enough, or aren’t as queer as some other people who choose/were born with/have the non-neo-natal yet relatively immutable attribute of exclusively liking folks of the same gender as themselves. It’s not a privilege to find yourself erased in media, or to hear derogatory messages about your identity from places that are supposed to be good at representing the ‘being gay is ok/awesome’ POV (read: that episode of Glee where everyone was a biphobic asshole). It’s not a privilege to be told by so many people (hello Dan Savage!) that it’s ‘just a phase’, or that if your sexuality happens to be fluid and it really was a phase, or series of them, it’s somehow less/not valid (see: http://pervocracy.blogspot.com/2011/08/praises-of-phases.html)

Moreover: to suggest that every bi person would really prefer to be in an other-gender relationship (esp. one that the heterosexist society at large would consider to be such) because of the accompanying perceived-to-be-heterosexual relationship privilege, AFTER talking about all the awesome qualities of the queer community, is really silly AND hurtful. Some bi people choose to only have same-gender relationships, because they really like not having the gender-related-privilege-imbalance, or because they really like being a member of the queer community (and they feel/know that they might be somewhat/totally excluded from their local community if they were to be in an other-gender relationship), or many other reasons which are probably not your business.

So yeah: as a straight person in an read-as-het relationship, there is a certain (and frequently large) degree of privilege. But queer people in read-as-het relationships are still queer, and any privilege they might have comes at the cost of pretending to be someone they are not (ie, a straight person). Which, as anyone who has been in some sort of closet or other knows, is a pretty high cost. Not to suggest that being in a read-as-het relationship is necessarily AT ALL totally less fun/fulfilling/etc as being in a read-as-queer relationship, or that being in a read-as-het relationship necessitates denying one’s queerness (obviously!!!). Just that if you have to pretend you are straight in the contexts of your relationship, how others perceive you because of your relationship, or at work, at church, at home or whatever, it FUCKING SUCKS. And I would say that this suckiness is about as near as it gets to a universal queer experience, regardless of what particular way you identify as not straight.

Love,

April Q.

I LOVE YOU AND THIS. Seriously, those were all of the feelings I had that I didn’t include in my aforementioned rant >.<

As to the "Being queer in a het relationship" thing, IT SUCKS. I dated a guy for two years and people constantly assumed I was straight. It made me upset, because I was constantly dealing with this internal struggle of "Do I correct them? Does it matter? I don't want to fuck them and I am content in my current relationship but this doesn't feel right." It was like they were putting me back in the closet. I also hated the assumption that I wasn't part of the LGBTQ community, it made me feel really isolated since I don't feel comfortable in the straight community.

And being forced to only date one gender would be a big fucking deal!!! I am attracted to people and not their gender, so this idea of excluding everyone but men from my dating pool just doesn't make sense to me. Finding someone attractive is not something I can just turn off, and the possibility of falling for a girl and then not dating her so I can keep straight privilege or whatever just makes my heart hurt to think about. Like there is really no way I can express how much that doesn't actually work, and this idea that it does seems to come from outside the bi community.

There seems to be this perception that bi people are part of the straight and gay communities, but in reality it is more and more feeling like we are welcome in neither.

Aw, thanks for the love!!!

I think the thing that many people don’t understand (or guess, in some cases, agree with), is that what makes me queer is that I am a girl who likes people who are not boys (ie, girls, as well as GQ, etc. people). Whether I also like boys is beside the point. For real.

Also, in addition to your EXCELLENT points about how difficult it can be to be queer in a read-as-het relationship, I just wanted to mention that it can also be very difficult/confusing/etc. to be a queer-girl-who-happens-to-also-like-boys who is in a read-as-queer relationship, for both similar and different reasons (usually the whole ‘I am not straight’ aspect of your identity would presumably be assumed/respected, but the assumption that because you like girls, you don’t like boys and/or if you like girls, you are less queer might be all over the place; or not, there are also lots of non-biphobic people, thank goodness :P ). Not to mention that apparently some exclusively-lady-loving ladies have arbitrarily decided to choose not to date girls who also like boys. WTF.

In bi / pan / queer solidarity,

<3 April

Hi! Thank you! <3 It's nice to see other eloquent people fighting against the constant tides of biphobia here.

Thank you for saying all this.

Personally, I’m in a gay reading relationship but I identify as bi/queer.

My girlfriend identifies as lesbian through and through and has in the past had little issue with my bisexuality. She still jokes around sometimes that I’m a big lesbian, and I do correct her.

I feel when i’m out on the gay scene, when I was single, I still got judged for being bi, and sometimes felt that it was viewed as wrong to talk about it. I never hid it though and would always be upfront about it.

When I’ve dated men in the past I do feel like I’m dismissed a bit by the gay community, like have to say ‘heeey, I’m queer too even though I don’t look it at first glance cause i’m with a dude’, but same in straight environments, I read as ‘lesbian’ looking and when single find it harder to pick up guys as they assume I’m gay.

Anyhow I don’t know what I’m going on about here..

Yay BISEXUAL CLUB :)

Just a question… are you familiar with the invisible napsack?

Being read as queer doesn’t come with privileges. Being part of a marginalized community doesn’t come with privileges.

Privileges are identifiable advantages. A queer person having privileges doesn’t make them less queer, nor does it mean they aren’t at all oppressed in some way.

You don’t have to be “this” oppressed to be queer. Whatever “this” is.

Take Ken Mehlman. He’s gay, gay, gay. But during his time in the closet he was just another privileged white dude. His success was built in the closet. He chose it. That he wasn’t being true to himself doesn’t actually cancel out the privilege nor take away from his past success. He wasn’t less gay during that time either.

While reading as queer does make you part of a marginalized community, it makes you part of a COMMUNITY. When bi/pan/queer people are in read as het relationships, they are both isolated from the straight community, whether people recognize that or not, and from the queer community. So while they may technically be getting straight privilege it is not without a price, a price that many of us do not want to pay.

I think that you are arguing that this straight privilege is more valuable than inclusion within the queer community, and as a person who has been through this situation I would have to disagree. I’ve experienced the marginalization that occurs in read as queer relationships, and I would honestly take it any day over the isolation I feel from the community in read as het relationships. To others the queer community may not seem so valuable, but that is how I and many other bisexuals/pansexuals/queers feel.

Of course, I feel this whole notion of a queer person having a choice in whether they want privelege or a community as absurd, as I do not feel that I can consciously just choose one gender to like. Because of this I have to navigate losing privilege or losing a community on a somewhat regular basis, and that causes me a lot of distress that is somewhat unique to the bi lifestyle. I’m not mentioning this to get in some sort of oppression olympics, just to point out that there are many issues unique to bisexuals that go unnoticed by the larger gay community. It is very frustrating to me as I know that it doesn’t have to be this way, that in theory I should be able to have a stable place within the community, but in reality I don’t. Of course, the only way this will change is if people within the LGBTQ community actually work to make it a more inclusive place for bisexuals, pansexuals, and the like.

Maybe it’s that people are assuming all or most queer people live in San Francisco or New York City or some other fabulous place with a large queer community.

When I say “community” I’m really referring to more of an idea than a physical place or actual group of queer people in close proximity to me. I live in a rural county. So I don’t actually know what you mean by having a stable place in the community.

For me the community is mostly a virtual place online I go to. I mean, this is it. Web sites like this. In which I sometimes feel like a proverbial punching bag for everything wrong in “The Community.”

Every single person that has posted in this thread IS my community. You are my community, and I don’t even really know you. You want me to be more inclusive, and honestly I don’t know what I can do. If you wanted, you could all move here and we can start a PFLAG together.

And now I’m going to get off the computer. And it’ll just be me and my partner at home, surrounded by straight neighbors. Then I’ll get up and go to work with all my straight co-workers and straight customers. And maybe I will see one other queer person who isn’t my partner.

Again this.

I don’t live in a place with a large queer community. For me, when I talk about community, I am referring to the internet just as much as real life. Sadly the internet community is fairly reflective of real life, and the biphobia I notice in our internet communities is very much mirrored within the real life ones. For me there isn’t much of a line between the two.

As for being more inclusive, it is as simple as not making exclusionary comments or attempting to draw lines between people, which is what biphobia is all about. When we say that people are making biphobic comments, we mean that people are saying “You’re not really part of this community- you have straight privilege, you can just chose, you’re going through a phase, you don’t actually know or have the problems that have brought us together.” And while you may not feel the community is super strong or a true presence in your life, it is very important to other people, especially if an online community is all they can get.

Being more inclusive is as simple as not saying such divisive, unfair bullshit, as listening when people say they feel like they’re being picked on, as calling people out when you see this sort of rhetoric popping up in comments. So no, we don’t have to build a PFLAG as you sarcastically recommended, we just have to stop being assholes to each other.

I was not being sarcastic about starting a PFLAG. I’m trying to start one in my county. Because for me, where I am, the problem is not LGBT people being assholes to each other, it’s straight anti-gay people.

If I am the problem here, I’ll just go. The Community? You can have it. I’m not finding it to be all that supportive.

As for my local area, I’ll go it alone. Today my local paper published yet another homophobic “Sodom and Gomorrah” letter to the editor about needing to protect the innocent children from the big bad gay. My main concern is for the kid reading that who has homosexual attractions, doesn’t know why, and is being told God is going to kill them for it. Or the parent who of that kid who believes they can, and should, try and pray the gay out of their kid.

You know why all this is happening? The LGBT Advocacy groups down in San Francisco and Sacramento decided we need to put LGBT people in school history books so as teach kids to be more tolerant. Which is all well in good, but they have no intention of devoting any resources to educate the ADULTS in rural communities who are flipping out. Why? Oh hum, it would not be strategically advantageous to devote resources to low population density areas as their strategy is to reach the maximum number of voters.

But I’m a lesbian! My cup runneth over with support from “The Community” both offline, online and everywhere! Yeah…not so much. Being a fixture in a marginalized community doesn’t amount to having some endless supply of support.

I’m just a person with a finite amount of resources and energy. And what you’re asking is for me to devote that to battling the queer community within. And you’re assuming that because I’m a lesbian I’m the recipient of copious amounts of support.