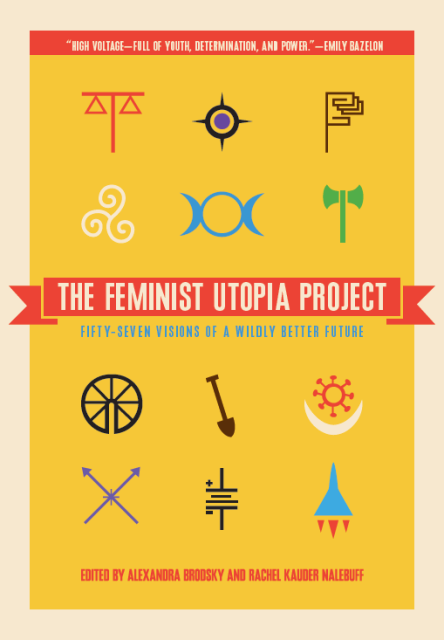

The Feminist Utopia Project: Fifty-Seven Visions of a Wildly Better Future is a brave book, both in what it asks its contributors to speak to, and in what it asks its readers to take away. Its strength comes from its breadth of perspective and the incredibly hopeful visions of all 57 people who contributed short stories, essays, interviews, comics, poems and photographs to build a composite view of how we would create — or what we would need to create — a “wildly better world.”

While a flipbook on the book’s outer margin depicts a rocket taking off, towards the wildly better world, the fact that the Project is an anthology of short contributions actually meant that it could stay pretty well grounded in the lived and varied realities of its contributors. One person didn’t stay holed up in a room for a year to write 350 speculative pages on utopia. 57 people wrote a few pages, and then went back to whatever they were doing. Common themes emerged, but each writer’s voice and vision were distinct, sometimes complementing each other, sometimes conflicting.

I will say, the bright red and yellow cover and its claims of a “wildly better future” made me brace myself for sunny depictions of a future of harmony and sameness. The singularity I associate with serious discussion of utopia made me uneasy. I wondered, can a utopian project be contained in a single volume, written and published in English, compiled and edited by two young women of somewhat similar relatively privileged backgrounds, that you can buy on Amazon? I wasn’t sure.

But opening the book, I was excited to find the table (designed as a wheel) of contents full of my own feminist heroes alongside people I’d never heard of. I was relieved to learn that a single utopia was not what editors Alexandra Brodsky and Rachel Kauder Nalebuff had in mind. “The collection of pieces in this book does not draw a perfect roadmap for a single, cohesive utopia,” they write in the introduction. “We started the project cautiously, knowing from our own organizing experiences that the quest for radical purity can come at the expense of urgent, ugly realities on the ground. …As one of our contributors asked us, might utopian thinking devalue those who adapt their strategies — for progress and for survival — to current conditions?” Instead of laying out a definitive blueprint or roadmap or set of ideals, Brodsky and Nalebuff invite the reader to join them and their diverse team of contributors in a creative and collective thought experiment to imagine what the world could be. This book is not a manual to create The Feminist Utopia; it is a process that you are invited to share in. Brodsky and Nalebuff hope that the book will “ignite your feminist imaginations to help you dream bigger.” Now that I’ve read all fifty-seven visions, I think they were successful.

The contributors take the utopia prompt and push it in all directions. Some prod at the question of utopia in a way that deepens the discussion from “What does utopia look like?” to, “How do we need to approach the question of utopia in order to make it something we want to see?” Melissa Gira Grant discusses how often, in conversations about sex work, the idea of envisioning what sex work does or doesn’t look like “after the revolution” is often used as a tool to exclude and erase sex workers from conversations about realities of sex work now. She pushes us to consider what we need to be shifting now to build a foundation for a future that is still far beyond our own lifetimes. Melissa Harris-Perry, relatedly, asks us to consider feminism as a method and considers utopia as a literal project, “to keep pushing the feminist question of what truths are missing, who’s not sitting at the table, whose concerns are not being articulated, whose interests aren’t being represented, and whose truths aren’t being told or acknowledged.”

Other contributors imagine specific components of the future in ways that would have never occurred to me, like Kate Riley and Richard Espinoza’s “What Will Children Play With in Utopia?” and Yumi Sakugawa’s comic, “Seven Rituals from the Feminist Utopia — Prebirth to Postdeath.” Some offer imaginative visions of the future that are also very specific critiques of present realities, like Mariame Kaba’s story “Justice,” which tells the story of the murder of a girl on a different planet by a visitor from Earth. She describes the other planet’s justice system, based on community, accountability and remorse, in stark contrast to how the American criminal justice system operates today.

Several contributors offered vignettes of their imaginings of the future: an abortion in the future, surrounded by supportive helpers; a young mother supported by her family and community, both as a parent and a student; radically varied family structures in a gender-variant world. A lot of the contributions written from the point of view of someone living in the actual utopia, often referring to the horrifying past (AKA present-day), didn’t work for me. They were sweet, but the absence of context for how those worlds came to be left me feeling more despair about the world we have than invigoration for the imaginary future. But then, I also found myself connecting deeply with a few of the narrative pieces in ways I didn’t expect. And even for those that didn’t sit well with me, I have appreciated the opportunity to reflect on why some of those narratives left me feeling unsettled or unsatisfied. Imagining utopia doesn’t need to be a comfortable project.

While plenty of the contributors are in their twenties, like Brodsky and Nalebuff, contributors range in age from their teens to their seventies. In interviews with movement elders, it’s fascinating and important to read about the ways in which they draw from the past in the course of imagining the future. Miss Major Griffin-Gracy asks for acknowledgement of trans women who have always been fighting for survival, before trans issues became widely understood: “What about the girls who suffered and died before there was a Laverne Cox?… There needs to be some appreciation of those skills and prior activism, and in this ‘real world’ we don’t get that.” Contributions from youth bring inventive takes on their worlds to the table. The last interview of the book is a group interview with a band of teen girls, Harsh Crowd, who talk about the power of making music and imagine a world where “good for a girl” is not considered a compliment.

I closed the book with more questions than I began, and I think that’s actually a marker of the book’s success in being intentionally incomplete and imperfect. While I was pleased to find a variety of different approaches to things that are important to me, including transformative justice, universal access to healthcare, radical teaching, and how to place social value on listening and empathy, there were also things that I missed. I noticed that, in many of the utopian imaginings, electronics were either entirely absent or low-key players. Given what a huge role our smartphones, social media and the internet play in the world we have now – especially in the context of building a contemporary feminist discourse — it left me desperate to know what the place for those things would be in a feminist utopia. So many of our relationships are mediated and facilitated by the speed of global communication capabilities — do those still get to exist in a feminist future? If so, how do we employ and develop this technology in a feminist way? If not, how do we keep the types of accessibility they’ve created for people who would otherwise be isolated or excluded from communities they’ve found on the internet? I have similar questions about traveling between places, and living lives that span the globe. How does mobility, migration, and citizenship work in the feminist utopia? How does a long distance relationship work in the utopia? How do our families spread across the world work in the utopia?

The contributors are the main event of The Feminist Utopia Project, but it’s also worth noting that the book is painstakingly and intentionally designed to uphold the principles of equity and transparency laid out by so many of its contributors. The table of contents is written in a wheel, and the front book flap encourages readers to start wherever they are moved to begin, disrupting the habit of giving preference to the first and last contributors. The book also notes how the money from the advance and book sales is being distributed. It might feel gimmicky, but it’s also cool to think about the little aspects of book design that can change and shift to break the norms of the publishing industry. I also think it’s useful that they prod you to read the book however you feel like — I powered through from page one to 346, and reading 57 different contributors in a short time was sort of challenging. Moving through at a relatively fast pace meant that a lot of the contributions blended together in my head, and because of how utopia is culturally understood and the quickness of the pieces, some of the writing grew a little tiresome. By the third story told from the POV of a narrator who can’t understand why people couldn’t breastfeed at the office in the Olden Times, written by a person with an amazing vision who also clearly usually writes analysis, I grew a little fatigued. That being said, I totally hope that there’s a future where breast-feeding at the office is no big deal, and I also loved that I got to see some of my favorite writers writing pieces that are outside their usual style. Reader, I advise you to take it slow.

I approached The Feminist Utopia Project with raised skeptical eyebrows. I closed it still feeling a healthy sense of skepticism towards a specific idea of utopia, but with a better sense of what exactly bothered me about it, and also with a lot of ideas about how “utopia” can be used as a tool in working to reshape our incredibly not-a-utopia of a present day world. The Feminist Utopia Project is an important work from people across the movement; you won’t regret picking it up.