Header by Rory Midhani

Header by Rory Midhani

feature image via shutterstock

High profile questioning of electoral integrity in US elections has been ongoing for over a year now. After losing the popular vote by nearly 3 million votes, Trump alleged that he lost due to illegal voting, despite the complete lack of evidence for this claim. Last May, Trump launched the “Presidential Advisory Commission on Election Integrity,” co-chaired by Vice President Mike Pence and Kansas Secretary of State Kris Kobach. The very next month, the commission requested extensive voter information from all 50 states, with Kobach writing:

I am requesting that you provide to the Commission the publicly available voter roll data for [State], including, if publicly available under the laws of your state, the full first and last names of all registrants, middle names or initials if available, addresses, dates of birth, political party (if recorded in your state), last four digits of social security number if available, voter history (elections voted in) from 2006 onward, active/inactive status, cancelled status, information regarding any felony convictions, information regarding voter registration in another state, information regarding military status, and overseas citizen information.

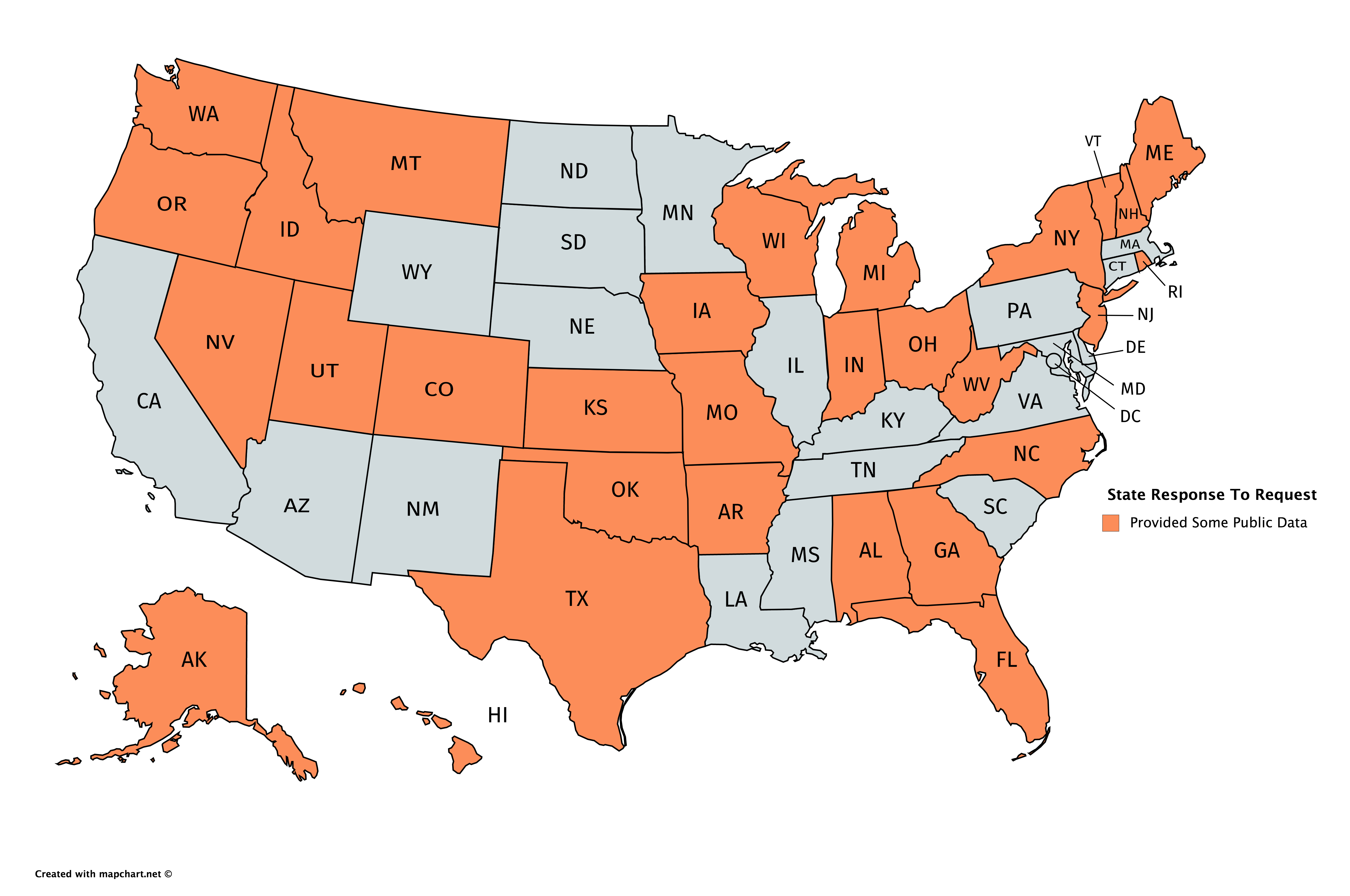

This invasive request was unprecedented and ill received. (The last four digits of voters’ social security numbers, by the way, is considered public information in exactly 0 states.) Among red and blue states alike, there was broad resistance. Republican Mississippi Secretary of State Delbert Hosemann memorably replied, “They can go jump in the Gulf of Mexico and Mississippi is a great state to launch from. Mississippi residents should celebrate Independence Day and our state’s right to protect the privacy of our citizens by conducting our own electoral processes.”

Although no state provided the full list of items requested by Kobach, many did eventually respond with some amount of public data. And this is where things get really dicey.

As of today, it’s unclear where that data resides or what will be done with it. Upon the shuttering of the commission last week, the White House issued a statement that Trump was directing the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) to essentially take up where the commission left off. However, attorneys for the administration have denied that the documents were transferring to DHS or anyone else, and as of Friday, DHS agency officials were saying that there were no plans for DHS to investigate voter fraud.

Maine Secretary of State and former commission member Matthew Dunlap — who began a lawsuit in November in an effort to force the body to behave in a transparent and bipartisan manner — wrote in a powerful editorial on Monday,

It may be that the president knows full well that there’s no evidence to back up his claim that he would have won the popular vote if 5 million illegal votes hadn’t been cast and that scuttling the commission will save his administration the embarrassment of facing those facts. The dissolution of the commission does not void the force of the District Court ruling, and I am still committed to obtaining the documents generated by the commission. In the American system of self-governance, the people have a right to know what their government is working on.

The president’s action shows that he never took the process seriously, and when it wasn’t going his way, he pulled the plug. The directive to move the commission’s work to the Department of Homeland Security is another hide-the-ball trick designed to find a different way to get the results that he and Kobach seek. But if I’ve learned anything in this process – based on the intense and passionate input from the American people – it’s that they won’t be able to do this in the dark anymore.

So! Here we are. Despite lack of evidence supporting Trump’s theory of widespread voter fraud, we continue to be plagued by the president’s conspiracy theory/inferiority complex over having lost to Hillary Clinton. We don’t know where all that data from the initial investigation is going, but nothing good will come of it, I expect. But while we’re on the topic — there is room for improvement in our voting system! And with midterms coming up (and a presidential election after that), it’s really important that we have a system people are able to trust.

Rather than continuing to chase the specter of voter fraud with shady commissions, invasive data requests, and voter ID laws that disenfranchise our community, here are three real ways we could improve electoral process integrity.

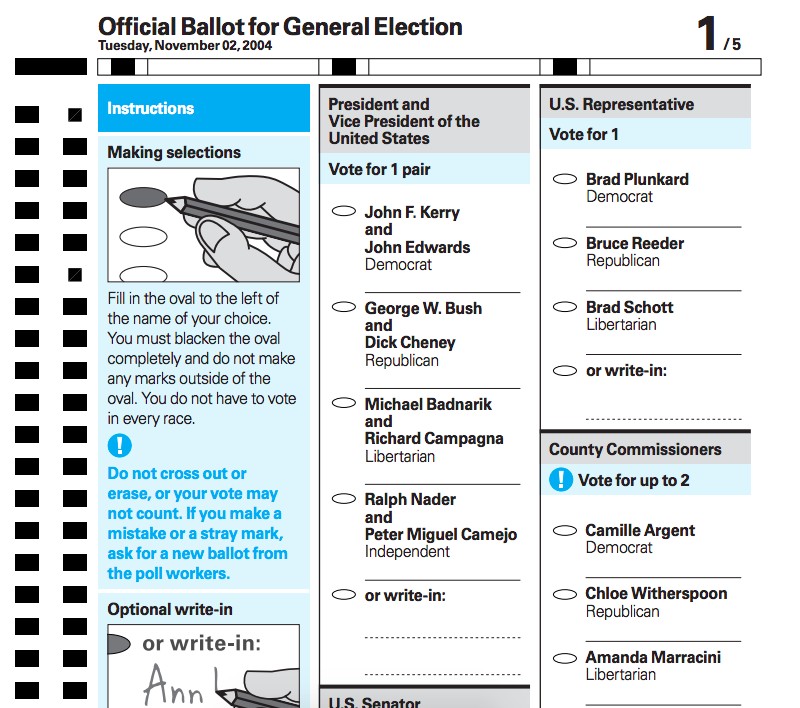

1. Design ballots with a human factors focus on usability, preventing invalid votes due to user error.

Psychology Professor Philip Kortum described the issue to Scientific American,

I think we’ve got two sets of problems. One is that the system is completely decentralized. The states are the ones who set the foundational rules for the elections, but every county creates its own ballots and its own rules about how it’s going to conduct elections. And so. we’ve got thousands of jurisdictions creating their own ballots, and the election officials are doing their absolute best, but they’re not trained in psychological science, and so they may not understand all the issues that could arise.

I think the other issue is that it’s not like you can create a ballot once and then say, Okay, this is perfect, and reuse it. You create a ballot, and then for the next election you have to create another ballot, and it may have different constraints, such as more races. So you’re constantly changing the content of what you’re presenting to users.

The solution? Follow good design practices when designing new ballots (The American Institute of Graphic Arts put together a great resource via Design for Democracy), and conduct ballot usability testing prior to election day to ensure that any new ballot designs are clear enough for voters.

2. Use cryptographic numbers to issue voter receipts, improving verifiability.

Here’s Massachusetts Congressional candidate Brianna Wu, responding to a prompt asking for a non cryptocurrency use of blockchain technology:

Blockchain is an ideal tool for ensuring fair elections. You give voters a paper receipt with a cryptographic number and publish a public ledger.

Which citizen cast which vote cannot be known. But anyone can make sure their vote was counted in the final public record. https://t.co/BM28DOJiZL

— Brianna Wu (@BriannaWu) January 1, 2018

An interesting idea. Not a serious policy proposal at this point (or at least, that’s how I’m reading it), but I absolutely love the approach Wu is taking here, leveraging her tech expertise and unique perspective to bring innovative ideas to the table on civic issues. It’s exciting!

For more thoughts on blockchain + voting, here’s Follow My Vote with an explanation of how blockchain works, and Dr. Ben Adida (who has a Ph.D. in Computer Science from the Cryptography and Information Security group from MIT) with some opinions on what such a system likely would and would not fix.

3. Add routine post-election audits, providing quality assurance backed by statistical rigor.

Right now, audits of election results are not part of normal procedure, and generally a Big Deal. They happen most often in controversial cases, resulting in lots of unhappy people at great monetary expense. One possibility for states to improve efficiencies in this area is to make audits a routine procedure, varying the size of ballots audited based on the victory margin.

“When the public policy space was less sophisticated about statistics, lawmakers picked a fraction of precincts or auditing units to examine—one percent or something like that,”[Computer Scientist Alex Halderman] told Ars. “But, over the past decade, the statistical science about election auditing has really blossomed.”

“You want to treat the process of auditing an election as a process of gathering evidence that the election result was right,” Halderman says. “You start examining ballots and you stop after you’ve gathered enough evidence to convince yourself at a defined level of certainty.”

“An audit isn’t necessarily a recount if an election result is not particularly close,” Halderman says. “You don’t have to look at that many ballots in order to audit it to high confidence. But if an election result turns on one vote, obviously you do need to look at every ballot to know that for sure.”

Such a policy would boost confidence in our voting system, as well as providing a strong deterrent to potential fraudsters. Senator James Lankford and Senator Kamala Harris have co-sponsored a bill proposing to do just that, creating an advisory committee of election security experts to develop the auditing standards. The Secure Elections Act is a bipartisan effort (three Democrats, three Republicans), and also includes incentives for states to eliminate insecure paperless voting machines.

In order for the auditing requirements to impact the 2018 general elections, it needs to be passed ASAP. Call your representatives and urge them to pass the Secure Elections Act today.

Notes From A Queer Engineer is a recurring column with an expected periodicity of 14 days. The subject matter may not be explicitly queer, but the industrial engineer writing it sure is. This is a peek at the notes she’s been doodling in the margins.

Comments

Amazing and awesome. Thanks so much for this concise and information packed piece.

Side note: I put chix thighs in the crockpot last night (based on the raging success of the Chicken Adobo recipe from AS). Yum!

@cmo_allthetime I am THRILLED to hear back on the chicken adobo success. :D :D :D

And thanks!

A fourth way: computerised districting methods that explicitly define the criteria for drawing electoral boundaries, optimising for things like equal populations in each district, and geographical compactness (read: no bizarrely contorted shapes like the NC gerrymander that’s currently in the news).

This WaPo article gives some examples: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2014/06/03/this-computer-programmer-solved-gerrymandering-in-his-spare-time/?utm_term=.2d432d29328e (although it’s very sloppy in suggesting that one guy invented this idea in 2010; people have been working on this idea for decades).

It’s not perfect; a purely automated approach sometimes gives impractical results. But it’s a much better starting point than letting legislators draw the lines as they see fit.

Some more about these methods here, focussing on the Australian context: https://www.geos.ed.ac.uk/~gisteac/gis_book_abridged/files/ch67.pdf

This is such a good one. Thank you for sharing!

How do you think we should handle voting machine errors/breakdowns?

I don’t have a tech-based answer, necessarily, but my dearest wish is that all states would adopt early voting and make it super accessible. So that when election day comes, most people would have already voted… and if a machine or twenty is down, no big deal; nothing is close to full capacity.

I’m a fan of vote-by-mail. Some states are all vote-by-mail (WA, OR). No voting machines means no machine errors. Plus, de facto early or absentee voting.

This is really interesting!

Thank you!