Ned Martel thinks everyone should be coming out on Thanksgiving. He thinks doing something so important to a large group of your relatives on the anniversary of our country’s colonization is a sign of the times, a signifier that gay people have nothing to be afraid of anymore:

This no longer needs to be such a big deal, even if this month’s election somehow emboldens waves of guess-what conversations Thursday night. Awkwardness is predictable, but expect the unexpected. A few years ago, a friend of a friend told his sister that he was going to tell their parents his news at the Thanksgiving dinner table. Seated and fretful, he listened as she spoke up first. Before he even got his throat cleared, she came out ahead of him. Nobody said this was going to be easy.

America is decades past the Very Special Episode phase […]

“When am I old enough to call my friends my family?”

I asked Libby via Facebook IM because I thought maybe she would know but she didn’t. She’s one year older than me, but she was just as lonely.

This Thanksgiving, I struggled with going home and making the decision to do so: having a dog and a job gave me solid excuses to skip, and I had alternate plans with friends in the DC area. Martel himself understands this dilemma, illustrating a choice between Thanksgiving with his family, his gay friends, and his straight friends. But what he fails to recognize is that all of his options involve a degree of honesty across the board I’ve never been able to experience. This year, I chose between Thanksgiving with my friends and my family – Thanksgiving as a homo or Thanksgiving as a mute face. I went back, booking a ticket three days in advance for twice what I’d typically pay, and prepping for an 8-hour bus ride back to New Jersey. Family holidays are like drinking, a habit I’ve sworn off more times than I can count but always come back to.

And so I was drinking bourbon cider in the basement when Libby IM’ed me and told me I could start calling her my family now, if I wanted. Thanksgiving was coming to an end, my cousin Brittany and I sitting on couches post-dinner and post-appetizers and post-small talk. This is our own tradition: exile from the adults where we drink and watch movies and talk shit. At that moment I was asking her over and over again to retell what I had told her at our family reunion in August, where I basically downed half a fifth of vodka and then texted Intern Grace that I’d come out to my extended family. Brittany wouldn’t tell me anything.

“It wasn’t anything we couldn’t have guessed,” my brother interjected. I took a deep breath. “It was all about how you live your life and none of us were surprised.” I breathed in and looked back and forth for a sign of exactly what that meant. Deep down, I think I was waiting for rejection – waiting for Brittany to announce, “Yes, you told me you were gay and my family is really disturbed by that.” And waiting for my brother to back her up instead of me, knowing well that he has his own home to go back to and a family that will be proud of him for the rest of time, no matter what.

Instead of asking again, I took another sip and waited for them to call us for dessert.

As a younger man at his Thanksgiving dinner table, Martel felt at times like we have all felt – like someone known to not fit into the script, like someone slowly waking up to an entirely different program:

Outsiders tend to see what’s what and who’s who. My sister-in-law wore a knowing expression, back when I would get into some cooking flurry around the holidays. Everything I made was en croute. I was distracting myself and others from the fact that I wasn’t doing what my Irish Catholic family has long done: going forth and multiplying. […]

I was noticeably different.

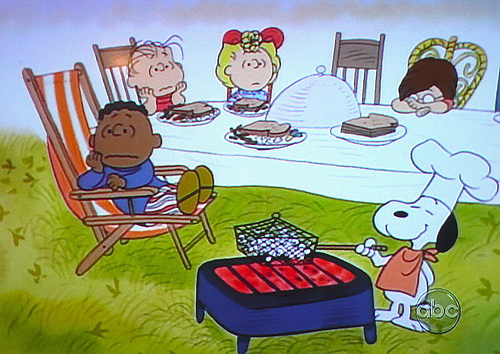

This year, like every year, I had sat next to Brittany and across from Nicole and her mom, right next to the head of the table – where her dad was sitting. My mom is usually next to her, but this year she brought home a friend so my mom sat next to both of them instead. Rocky sits next to Brittany and kept grabbing my booze and I would pout and hide it on the floor under my chair every time he was done pouring it. My mom kept rolling her eyes. A big golden retriever was roaming around and the extended family members all sat at the farther end of the table pushing into the living room, two little boys and four adults crammed around a second table. This is our typical crowd, our annual floorplan of my family, my cousins, and their extended family: every relative able to come sitting in their previously-assigned chairs. The same place, the same time, every year.

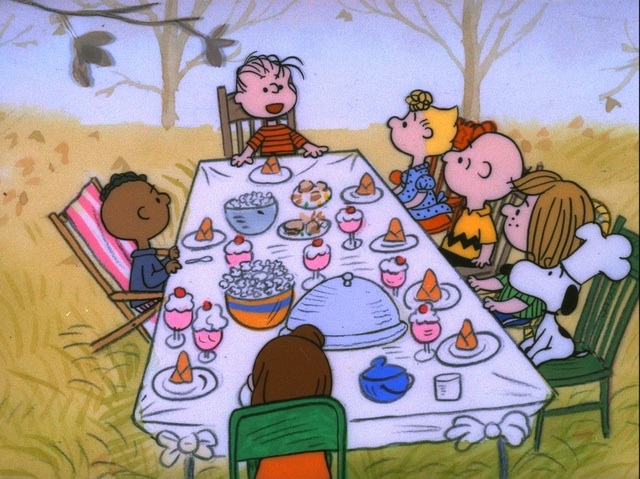

It is at this moment that we appear to be a cohesive, normal, peaceful and well-arranged family unit. I realize we are all smiling, all waiting, and all in rhythm for the holiday. We all sort of know our roles, and so I figure that that moment is why people do this, or at least part of why they do. Martel insists that in “gay America” there should be a place at the table for the queers, even if it does feel a little like the Puritans and the Natives sitting across from each other in suspense. But my place at the table is an accident, something given to someone I am pretending to still be. The entire table, just like the one at that first Thanksgiving, is built around a lie. A figment of everyone’s imagination.

The night before, my mom tousled my hair and said something about how attractive boys must think I am now that I look so pretty and clean. I walked away from her.

I used to talk a lot at the dinner table; I would act obnoxious and piss off my conservative relatives and then engage them in arguments I knew I could win. Once, with eyes wide and jaw on the floor, my cousins’ in-law said to my mother under his breath, “your daughter is very articulate.” He was shaking his head, sort of horrified but also sort of in awe of my conviction, I think. But this year I was relatively quiet, just taking cheap shots at Rocky and pouring booze into my cup. It’s been like that for two years now – me at the dinner table sort of afraid to speak. Sort of afraid of what I’ll say.

Two years ago, I had planned a very public, grandiose coming out: I would stand up in front of my neo-con cousins and just say, very plainly, “I’m very thankful for other women and the opportunities I will have to sleep with many of them in the near future.” I wanted to say it in the middle of everything, while people were still passing the turkey. But instead I just fidgeted silently and texted Danny from under the table. We drove home and then we went shopping on Black Friday. My mom bought me plaid shirts, men’s sweaters, new leggings, and thick socks.

I told my mother in the car the next day that I liked someone at school, that she was a girl, that I was confused and I wanted to talk to someone I loved, like my mom, about it. My mom cried until I got out of the car. We never talked about it again.

In fact, we don’t talk about it at all, except when we do, mostly by resorting to small words and gestures to piece together an elaborate and much-needed dialogue. When we shop my mother urges me to “please stop shopping in the men’s section,” and now she sorts what she likes and doesn’t like by “how feminine it is.” Once she got angry at me because I said she couldn’t possibly love me if she didn’t accept me for who I was, and she told me I was wrong.

Martel experienced all of this, packaged instead as an offer to enter the priesthood for a large sum of money, a last-minute saving grace for someone who was clearly never coming around to his heterosexual prime. But in Martel’s story, it ends. In Martel’s story, the truth heals all. And I think about whether that’s how it would go in my family.

This Thanksgiving my brother made fun of me for being broke and said something under his breath about how I’ll never have a family. Earlier during appetizers my cousin looked over at my side of the table and declared, “I am definitely the most womanly person in the dining room.” I took a sip of cider and poured a new glass, leaning low to pour it under the table by my chair.

But despite all that, this year I didn’t think about 2010. Not for a long while. And that’s different.

In 2010, when I got back to DC after Thanksgiving, I sent my mom an e-mail stating that I wanted to come for 48 hours instead of 14 days for Christmas. I was willing to miss my best friend’s birthday and any extra gifting or relatives or shopping. I made plans to go home with other people, should she tell me my entire stay was rescinded. But instead she insisted I come back, so I did and the whole mess hung in the air like when skunk smell gets stuck in the car A/C. Last year, it haunted me as well; I came home practicing self-medication and never looked up from my phone. It was the incident that ended my long visits and short vacations and weekly phone call regimen. It was something that had altered the very fabric of my family.

I started to feel a seismic shift in my life where my friends became the only people who knew who I was, and my family remained attached to the past and to someone I couldn’t be anymore and didn’t understand. My friends wanted to save me, and my family reminded me that I was a girl who needed to be saved.

I used to be best friends with mom and my cousins, and I used to tell them everything. Now I was wondering what my cousins knew or had inferred or had seen on the Internet and was biting my nails wondering if I came out to them at the summer reunion. I felt like a liar and I realized that once again I had nothing to say at the table.

That was when the questions began. Why am I doing this? Why am I, a person typically unwilling to bend to fit into anyone’s life, doing my best to keep my mouth shut and fit back into the past? Why am I so obsessed with the idea of being honest with people who have made it clear that honesty is not the best policy anymore? When Ned Martel came out he began to view himself as the person at Thanksgiving who shakes things up, who keeps things different and exciting. His family appreciates what he brings to the table and who he is, and how his differences bring variety to their own experiences. But I just want to know when I sit at my seat at that dinner table that everyone knows who I am. I just want to stop feeling like a stranger.

This Thanksgiving I managed not to mention that I write, that I’ve travelled, or that I’m a dyke. In fact, I hardly got a word in edgewise.

I want to come out to my family because I want to come out to everyone, to the whole planet. I want animals in the rainforest and train conductors and bus drivers to know I’m gay. I want the cute lesbians who work at Starbucks locations across the Earth to know I’m gay. I want my professors, my employers, and my coworkers to know I’m gay (which might be why I wrote it in all of my cover letters). But I want to come out to my family especially because I love them. And when you love someone, you tell them the truth.

My grandma shoved 30 dollars in my hand once and told me, “Always tell the truth about who you are and know we’ll love you anyway.” It sounded familiar to me, like something my mom had said before that car ride in 2010. I wondered how my mom would feel if I blurted out the truth she hasn’t been able yet to repeat, if I had taken the 30 bucks and crumpled it in my pocket and just fallen onto my grandma’s bed and told her that I’m gay, that I told mom and it wasn’t at all what I expected, that I’m sorry I don’t call but I never know what I can tell anyone in this family anymore without being unsafe about keeping the rest a secret. That I feel like that car ride was a litmus test and I failed, and that my mom’s reaction and continual silence on the matter sound overwhelmingly to me like an instruction to never talk about it again, to anyone. That in more ways than one I’m still chipping away at pieces of 2010, and it’s mostly the wreckage that’s still left.

Martel’s family saw him receding and brought him back – asked him for the truth and then healed the damage from not asking sooner.

I have six nephews and nieces of my own, and a family who pulled me home when my relatives sensed me running away. I wasn’t, really; it just looked like that to them. The Martels know my sexuality hasn’t torn at the family fabric, and my coming out, somehow, makes us whole. So, sure, I’ll have dinner with the family that raised me.

My family has never managed to stutter out the question.

I am afraid to attempt a larger, familial-based coming out situation without my mom’s support. I am terrified to tell my conservative cousins the truth without knowing, for a fact, that she has my back at that dinner table. So this year on Thanksgiving I took the same seat I always take and when I finally remembered 2010 I made sure to remind myself that I was lucky to be there at all. I thought about how relatively okay my situation was, how silence is better than making a noise that leads to abandonment or physical danger or fucked-up therapy. I vowed to forgive, in advance, every single offense I took at the table, and remember that my family has flaws and it isn’t their fault that I’m living on the fault line.

Despite how we move and progress as a culture, each family remains a thing to be studied and considered and appreciated, and then conquered. Discussions about sexuality remain difficult and, for many of us, seemingly impossible or impractical. Coming out was, is, and will be – at least for a little bitty while – hard, scary, and sometimes even dangerous. And I think it’s okay to be afraid. It’s great that for Martel, Thanksgiving was the right place and time to come out. But he’s wrong that “Thanksgiving is the proper holiday to tell your family that you’re a homosexual.” For some of us, it’s never going to be the proper time. And for some of us, there’s already too much potential for heartbreak sitting on the dinner table for us to push ourselves any farther. At least right now.

I still want my big coming out at the dinner table, right from my own chair where I’ve sat since I was promoted from The Kid’s Table. I want to be sitting next to Brittany and I imagine that when it happens I’ll be fearless, looming above the turkey and grinning like a dipshit. I imagine, too, that it will be a turning point and we will finally be able to talk to one another again over gravy and biscuits.

I don’t know when I’ll be ready for that to happen. But I know I will love everyone at the table more in that moment than I ever have before.

Special Note: Autostraddle’s “First Person” personal essays do not necessarily reflect the ideals of Autostraddle or its editors, nor do any First Person writers intend to speak on behalf of anyone other than themselves. First Person writers are simply speaking honestly from their own hearts.