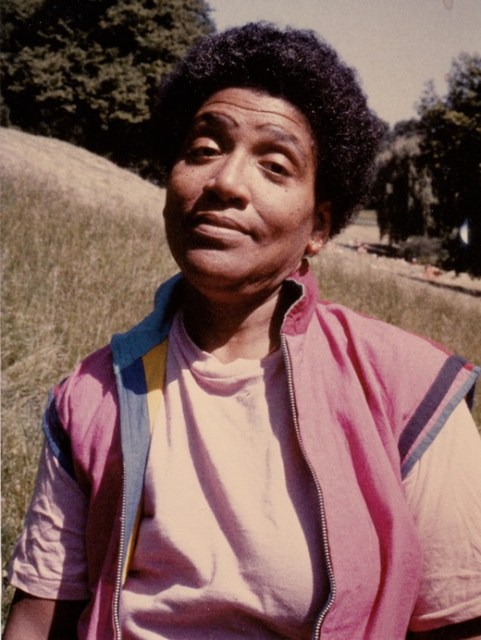

Year of Our (Audre) Lorde is a monthly analysis of works by queen mother Audre Lorde as they apply to our current political moment. In the spirit of relying on ancestral wisdom, centering QTPOC voices, wellness, and just generally leveling up, we believe that the Lorde has already gifted us with the tools we need for our survival.

Comfort, like so much other aid we seek, is in short supply. The relentless nature of election cycle coverage, of coronavirus and rampant xenophobia, are the symptoms, not the disease, of apocalyptic thinking that has come to organize so much of our daily lives. In the time between when this piece is written and when it’s published, who knows what the stakes will be. No longer a threat, the reality of a global pandemic has fully exposed how deeply unprepared the people who allegedly govern us are for such a situation; our very lives the potential casualties to their political hubris. Too often those who stand on the same side of justice fights fall prey to a divisiveness that threatens us almost as much as the ill we’re fighting.

One of the biggest lessons of Audre Lorde’s work, I believe, is the beauty and strength of coalitional politics. Building a coalition, a mix of people that spans races, genders, ages, and beliefs, is an inherently fraught process. But it’s also necessary work. How we go about the task of making this world inhabitable for us all matters. How is it possible to achieve freedom, from all forms of oppression, if we do not work together?

Audre Lorde’s life stands as a testimony to this, but she also delineates the cornerstone of her approach in the essay “Poetry is Not a Luxury.” Here, she defines poetry as “the revelation or distillation of experience, not the sterile word play that, too often, the white fathers distorted the word poetry to mean — in order to cover their desperate wish for imagination without insight.”

On first encounter with this essay, I resisted it, feeling unable to detach my understanding of poetry from that shit I wrote really badly in my teens. I couldn’t conceive of poetry as an approach, as an articulation, largely for the reasons she explains here: We’re so often taught to understand poetry as being purposefully opaque; one of the form’s primary objectives is not to directly state the meaning of your words. Reading that type of poetry can certainly bring on a particular sense of discomfort, but what Lorde lays out for us is the potential and proximity borne out of a shared poetic language. It’s an understanding of each other and of what each of us must do to better our circumstances.

“The quality of light by which we scrutinize our lives has direct bearing upon the product which we live, and upon the changes which we hope to bring about through those lives. It is within this light that we form those ideas by which we pursue our magic and make it realized. This is poetry as illumination, for it is through poetry that we give name to those ideas which are, until the poem, nameless and formless-about to be birthed, but already felt.”

I think that how a task, a movement, is executed is just as important, if not more so, than the fact that it’s executed at all. This gets muddied, and fairly quickly, when we begin to turn that gaze on our justice movements. The fuzzy outline is easy enough for most of us to agree on, but the fine point, contoured work of details is usually where the fabric begins to fray and thin out, to the detriment of those most vulnerable. Although Lorde specifically names women in the next passage, I think we can interpret these words for all marginalized peoples:

“For women, then, poetry is not a luxury. It is a vital necessity of our existence. It forms the quality of light within which we predicate our hopes and dreams toward survival and change, first made into language, then into idea, then into more tangible action. Poetry is the way we help give name to the nameless so it can be thought. The farthest external horizons of our hope and fears are cobbled by our poems, carved from the rock experiences of our daily lives.”

I need a movement that can hold my anger. I need a movement that can hold my contradictions. I shouldn’t have to qualify my rage when speaking out about injustice. We don’t have time or need to entertain tone policing and calls for respectability. Rage and condescension are not the same thing, yet often both are aimed at the wrong target. Our current political climate has crystallized this for me. The venom hurled between some on the left at others on the left is as baffling as it is sad and a waste of energy better spent elsewhere.

I take Lorde’s words to heart when she says “Possibility is neither forever nor instant. It is also not easy to sustain belief in its efficacy.” I believe movements, like people, require immense amounts of patience and fluidity. From the individual to the collective, we need to reflexively resist the stasis fashioning itself as ethical purity, self-righteousness, and over-assuredness that your method is the method. As the term “movement” implies, we have to always stay in motion, stay open to critique and also to better ways of carrying out the work of liberation. As she cautions:

“When we view living in the european mode, only as a problem to be solved, we then rely solely upon our ideas to make us free, for those were what the white fathers told us were precious. But as we become more in touch with our own ancient, black, non-european view of living as a situation to be experienced and interacted with, we learn more and more to cherish our feelings, and to respect those hidden sources of our power from where true knowledge and therefore lasting action comes.”

Lorde doesn’t divorce our need to feel from our need to act. I find myself tempted to read disavowal into what she is saying. But as with so much of her writing, Lorde instead extends an invitation to move closer to one another, to reject the comfort of putting distance between our thoughts and our actions.

“Right now, I could name at least ten ideas I would have once found intolerable or incomprehensible and frightening, except as they came after dreams and poems. This is not idle fantasy, but the true meaning of ‘it feels right to me.’ We can train ourselves to respect our feelings, and to discipline (transpose) them into a language that matches those feelings so they can be shared. And where that language does not yet exist, it is our poetry which helps to fashion it. Poetry is not only dream or vision, it is the skeleton architecture of our lives.”

How will you bring poetry into your freedom practice? How are you finding space for your full self, beyond problem-solving and productivity, in the midst of our present circumstances? Drop a note in the comments!