Feature image via Lambda Legal

The Texas Department of Criminal Justice failed Passion Star at every turn, according to her accounts in interviews with The New York Times and in a letter to Jezebel. It failed to protect her from gang abuse, numerous rapes, and other violent attacks. It failed to react effectively to the complaints she filed and requests she made to be placed in special housing for vulnerable inmates. It kept her in prison even after her ex-boyfriend, who played the lead role in the kidnapping they were both convicted of, was released.

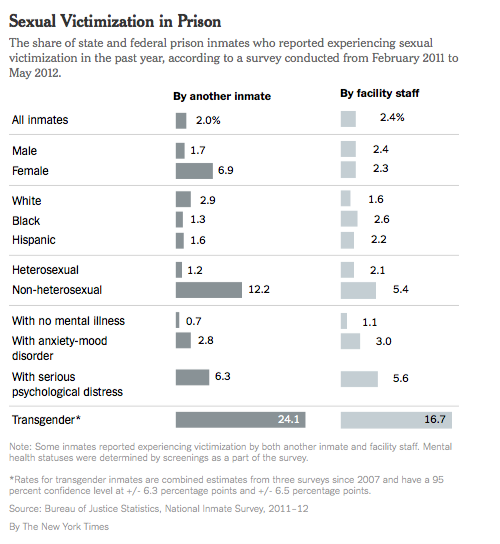

Passion Star’s harrowing narrative of rape and abuse has quickly come to symbolize an overall culture of violence and sexual assault in prisons that disproportionately affects queer and trans inmates. Experiencing mental illness or distress also increases an inmate’s risk of assault. The New York Times breaks down the statistics, largely based on data from 2011-12:

Texas has by far the largest inmate population and an even higher number, proportionally, of prison assaults. Five of the most sexually violent prisons in the U.S. are in Texas, according to the Justice Department. And yet former Governor Rick Perry, and seemingly his successor Greg Abbott, have declined to formally comply with the Prison Rape Elimination Act requirements designed to keep prisoners safer from sexual assault, even though the requirements have been available since 2003. Perry called the requirements cumbersome and expressed concern that they would endanger prison staff. State officials say their “goal is to be as compliant as possible with PREA standards without jeopardizing the safety and security of our institutions.” Lambda Legal has spearheaded a campaign to urge Abbott to comply with PREA, to which he has not responded.

Today is the deadline for states to confirm their compliance with PREA. There is no indication that Texas, or the five other states activists call “renegade states,” Arizona, Florida, Idaho, Indiana and Utah, have plans to do so. The opt-out penalty? A five percent reduction in corrections-related federal grants. Texas leaders have confirmed this will make no real dent in their corrections budget, which amounts to billions of dollars.

The obstinance of Texas and other states is alarming, and so is the slow progress of implementing PREA so far nationwide. Plans to audit all corrections facilities by August 2016 are substantially behind schedule — so far, only 335 of more than 8,000 facilities have received inspections.

President George W. Bush signed PREA into law in 2003 after decades of studies showing 5 to 20 percent of inmates experienced sexual assault. PREA itself conservatively estimated that 13 percent of inmates have been sexually assaulted while in prison. The law’s slow implementation means inmates continue to suffer — and those inmates disproportionally are trans and queer.

Many eyes are on Passion, but the urgency to stop prison rape has faltered in the 12 years since PREA passed, the Times notes. Regulations won’t do much if prisons and state governments don’t have cultures of taking sexual violence seriously. When so many assaults are at the hands of guards themselves, it’s hard to believe those same guards will commit to protecting inmates even when their worksites are technically compliant with PREA’s rules. In Texas, for example, 21 of 24 facilities examined by auditors do meet all PREA requirements, according to a state official, and the other three await the completion of the auditing process. And yet the data shows Texas inmates experience high rates of sexual assault, including in some of those audited facilities.

When Passion first arrived at Telford Prison Complex in 2002 at age 19, she identified as a gay man. She was almost immediately identified as a target by a gang leader, who forced her to perform sexual acts in exchange for “protection.” She told the Times:

“In the state of Texas, in the general population, there is a culture where gay men and transgender women in prison are basically preyed on by the stronger inmates. They have to be the property of a person who’s in a gang, and this person is the individual who speaks for them. So basically, they’re coerced into being sexually active to survive.”

Over time, she realized she was trans, and the violence continued and worsened, but coming out was vital for her. She told the Times:

“You know how penguins are? On land, if you look at a penguin when it walks around, it’s just an ungainly, clumsy creature. But in water, a penguin is one of the most graceful animals in the world. I didn’t feel like I was in my element until, at all types of personal risk to myself, I became Passion.”

Passion has not been able to pursue medical therapies related to her transition but hopes to eventually. The Texas penal system has been far from supportive of her transition and still refers to her as male and by her birth name in all official documents because she has not been medically identified as trans.

But no matter what, notes Lambda Legal attorney Jael Humphreys, “whether or not she was diagnosed as transgender has nothing to do with whether or not she deserves protection from sexual assault.”

Passion first started filing formal complaints about sexual abuse in 2003. Over the next decade plus, she has spent time in multiple facilities and experienced the same abuse from inmates and guards and lack of help from officials in each one. She gained a reputation as a snitch, which only put her at higher risk. She was placed in solitary confinement on multiple occasions as a means of protecting her. Now, she’s back at Telford, this time in the program they call safekeeping, which partially separates inmates at high risk of harm from the general population. But that came only after months of fearing for her life on a daily basis and — perhaps not coincidentally — a few days after the Times called the state to ask for an interview with her.

When Passion learned she would be put in the safekeeping housing, she was “ecstatic,” she told Jezebel.

Really, I felt relief and felt that just maybe I’d now be allowed the opportunity to survive long enough to make it home to my family. Then, in another way, it felt crazy coming back to Telford Unit, where I made my 1st requests for protection. I can’t help but think about the violence I could’ve possibly avoided had my complaints been heeded then.

The state had previously rejected her requests to be placed in safekeeping, citing her disciplinary record — which she says she only had because she had to protect herself when the prisons would not do so. Passion, with the help of Lambda Legal, has filed a federal lawsuit against the state for failing to protect her despite her many pleas for help.

It may be that a successful, highly publicized lawsuit will light more of a fire under Texas than a 5 percent loss in federal funds to the Texas government. If nothing else, perhaps it will lead for some justice and some peace for a woman who may be locked up until 2022. Her story, like those of CeCe McDonald and Monica Jones, highlight the incredible challenges for black trans women in prison — especially in men’s prisons, where the majority are housed, as Mey wrote. Those challenges include sexual violence, lack of access to necessary medical treatments like hormone therapy, and a refusal to recognize their gender. Not even a full implementation of PREA can protect women like Passion from the inherent violence of U.S. prisons, which Maddie and Mey have written about before. The criminal justice system does not have structures in place to effectively protect black trans women, or any other vulnerable prisoner, from violence.

Comments

This really just saddens me. I take that Times statistic is mostly for trans women? Are there statistics for trans women in Women’s correctional facilities?

This exact same issue exists in the many INS facilities (which are, at core, also prisons) where trans women are put into men’s facilities and face frequent attacks and sexual assaults from other detainees and guards. Both of these situations have been going on for years, yet do you ever hear this discussed by mainstream LGBTQ organizations? No, because it’s a population which doesn’t bring in the donations.

Questioning how a small budget cut would be an appropriate penalty for prisons. It seems like that would only lead to cuts in spending on care for inmates.

Wow, some numbers in that chart I totally wouldn’t have guessed. For example, whites report assaults from their co-inmates at more than 2x the rate of blacks, and women at more than 3x the rate of men. Clearly I need to adjust my prison stereotypes.

Sadly, the numbers for gay and trans folks do not surprise me.

thank you for this article.

it is ABSURD that these states aren’t even pretending to implement PREA. but i’m also skeptical about its effectiveness in stopping sexual violence at all. like you said, full implementation of PREA can’t guarantee safety. sexual violence is an inherent part of the prison-industrial complex. i worry that the long-term implementation of PREA will ultimately allow people-in-charge to pretend sexual violence isn’t happening because prisons claim to be compliant with the law.

In Argentina’s Constitution we have art. 18, that says: “[…] The prisons of the Nation shall be healthy and clean for security and not for punishment of the prisoners confined therein […]” The punishment is taking your freedom away for your crime; the rest is just cruel and unusual punishment.

But the irony is that we don’t consider prisoners as human beings so this is a bunch of dead letters. And I’m pretty sure that this consideration applies to most countries. It’s worst if you add to that what some people think about queers and trans people.

Prison Rape Elimination Act also sounds like dead letter too, especially if you consider that your way of enforcement is just taking 5% of federal founding. I think the same about those “zero tolerance” policies for sexual abuse or assault, because you mean zero tolerance like in the Army and Universities? This kind of policies required real action, no empty declarations.

Something that I don’t really understand or maybe I’m reading it wrong, is that if you’re trans you almost need to be considered or declared sick to get your hormonal treatment or have some special accommodations if you decided not to transition yet. I do apologize if I’m misunderstanding the issue, because that was not my intention. That even sounds crazy while I’m typing this.

re: your last point. it’s my understanding that you are completely correct. in most, if not all, circumstances for incarcerated trans people in the US (i don’t know anything about rules and regs outside the US), a diagnosis of gender identity disorder is necessary to access any type transition-related care. this is a really good article by Chase Strangio explaining this further, along with the dilemma that the push to get GID out of the DSM creates for incarcerated trans people because of the need for diagnosis to access care while incarcerated. it’s dense, but thorough.

Thank you very much for the link, you were right it was a bit dense, but very informative.

GID in the DSM sounds, for me, very similar to the way that APA considered homosexuality previous to 1974.

But I do believe that the concerns raised by the author are real, specially for trans people in prison. Elimination of GID from the DSM may work for trans people outside of prison, but inside it will make life impossible.

After reading the article, I was thinking that the big problem is the excessive power that the Prison Industrial Complex has over the life of any person, in any healthcare situation.

I have a final question, maybe you can help me with this too. Do you know if any state in the US has a project or is working in a “gender identity law” (but not the Republican way)?

In Argentina we have a Gender Identity Law, Nº 26.743, that, of course, also applies to prison.

Gonna put the link here; the only english translation I’ve found comes from a paper from the University of Toronto, and it’s pretty accurate.

http://www.academia.edu/4158706/Argentina_SOGI_Legislation_Country_Report_20131

I was hoping for further breakdown of the figures presented here. In particular – of the women who cite sexual assault – what is the difference in figures between trans and cis women with location as a variable? That would be a more meaningful figure because it would let us understand (theoretically) the instance of sexual assault within female prisons and male prisons towards an individual.

Equally, I feel some attention should have been given to trans men and their experience of the prison system, given that the overall narrative is dominated by trans women currently.

I know people dislike separating the two, however for the purpose of this study, it would be meaningful to distinguish social categories for the identification of needs assessment.