Last March, I met filmmaker and scholar Alexandra Juhasz outside the Wexner Center for the Arts in Columbus, Ohio. She was in the middle of a Film/Video Studio Residency at the Wex, as it’s known as here in Columbus, working closely with an editor on post-production of her experimental documentary Please Hold.

Please Hold, which premiered earlier this March, explores the intersections of activism, memory, and media via a profoundly personal yet communal lens. It is anchored by videos of two of Juhasz’s closest collaborators and late friends in the last stages of their lives. Shot on a mix of consumer-grade recording devices — iPhone, Zoom, VHS camcorder, and Super-8 film — the documentary is an homage to grassroots AIDS mediamaking across decades and its ability to capture intimate, honest communication about hope and loss.

I was profoundly moved that Juhasz invited me into the studio with her to watch a cut of the film. A prolific writer and filmmaker, Juhasz is a Distinguished Professor of Film at Brooklyn College, CUNY. She produced and acted in the renowned feature documentaries The Watermelon Woman (Cheryl Dunye, 1996, and its remaster, 2016) and The Owls (Dunye, 2010). For decades, Juhasz has written, directed, and produced her own documentary features and shorts, which have screened widely in feminist, queer, and experimental documentary festivals. She has written extensively on HIV/AIDS, including the recent publications We Are Having this Conversation Now: The Times of AIDS Cultural Production with Ted Kerr and AIDS and the Distribution of Crises, edited with Jih-Fei Cheng and Nishant Shahani.

I first encountered Juhasz’s writing in grad school while studying LGBTQ media, history, and activism. Her book AIDS TV: Identity, Community, and Alternative Video, deeply shaped the way I theorized about LGBTQ local television in my own work. While preparing to begin my dissertation, I emailed Juhasz for advice about how best to write about these topics. I was looking for possibility-models, other scholar-activists who do research in the service of social justice and queer community. Since then, Juhasz has supported my work in many ways, including connecting me with media makers I interviewed for my dissertation.

As we watched the documentary together in the studio at the Wex, I realized that Please Hold honors one of these same media makers: Juanita Mohammed Szczepanski, a Black disabled queer feminist media activist who died in 2022. I spoke with Szczepanski years earlier about her work creating AIDS education media for the Audio-Visual Department of the Gay Men Health Crisis in the 1990s, after Juhasz connected us. I hadn’t realized the film would document Szczepanski’s last days. Watching the film next to Juhasz and her editor, I realized we were both holding Szczepanski’s memory, and our connections to her, in different ways. To know Alex Juhasz is to be held in community, a privilege and an honor that connects you to her own deeply felt responsibility to making the world a more livable place for marginalized people.

It was a pleasure to speak with Juhasz more about the film’s production, how it explores grief and loss, her approach to activist media making and distribution, and the importance of LGBTQ communities of care. Our conversation below has been lightly edited and condensed. Please Hold is available to watch for free on the film’s website and you can book a screening of it here.

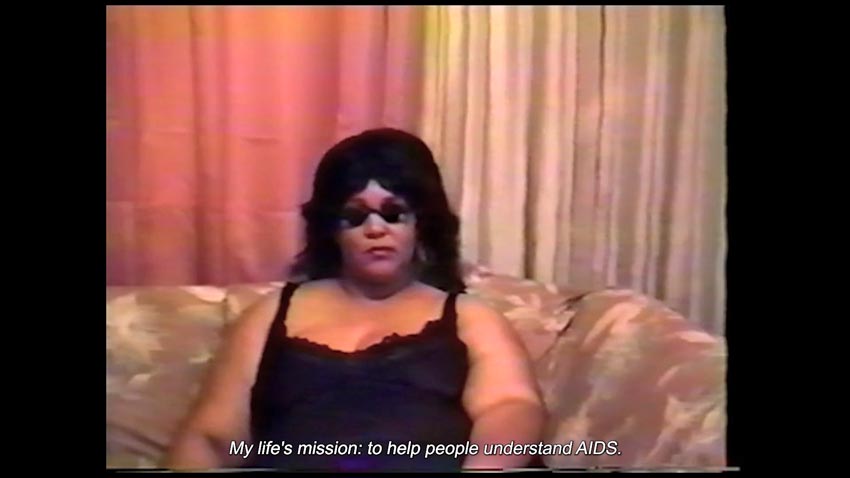

Juanita Mohammed Szczepanski in “WAVE: Self-Portraits” (The Women’s AIDS Video Enterprise, 1990, VHS).

Lauren: Could tell me about the origins of this project and what inspired you to create it?

Alex: Thank you for asking. This video began because, during the COVID pandemic, my very good friend and a collaborator of mine on AIDS activist media, Juanita Mohammed Szczepanski, asked me to shoot video tape of her in the process of dying. She more or less chose the terms of her own death because she stopped receiving dialysis.

I came to videotape her twice in rehab centers in New York. And after that, I made a video that she had wanted from those materials called I Want to Leave a Legacy. When I was making that video, I realized that at a previous moment in my life, another very close person to me had asked me to make a video with him in the late stages of his life. That was my best friend, James Robert Lamb.

I wanted to think about the responsibility of holding those two documents, but also how they produced this very clear arc about some histories of HIV/AIDS in the United States, which is to say, my friend Jim is a sort of poster boy from the first years of the pandemic: gay white man, very pretty, an actor. He died when he was 29 years old. There was no medication, and he had a very painful death. The videotape that I shot of him all those years ago when we were young was very strange actually, because I think his mental state was affected by his impending death.

And then fast forward 30 or so years: Juanita is a Black disabled woman who’s a lifelong AIDS activist, who doesn’t die of HIV, but dies in community that’s been produced around collaborative art making and is really committed to disability justice and dies within the time of COVID and because of health inequalities that were escalated because of COVID.

My responsibility, what I can learn from those tapes, what they tell me about HIV/AIDS, and also what they tell me about living through dying, and making community even as people are dying — that’s what started it.

Lauren: Can you tell me how the film itself explores grief, memory, loss, and those relationships?

Alex: The video wants to think about technologies of memory, various receptacles that hold something of a person that you loved after they die. It could be a trace of them, but it could be work you’ve done together. This is very important to this project. They are people that I engage in art making and activism with. I know that various technologies shape memory and shape grief differently.

So, it really wants to think about how VHS, which is what I shot Jim on, has a different almost metabolism than an iPhone video, which is what I shot Juanita on. While they are both media that are holding traces and memories and conversations and activity with these people, I think that they’re held differently.

I was thinking about those two media to think about material things, like in the case of the film, a sweater and a scarf that emerge. Then I extend that to my own body and I think about the fact that I’ve aged. Grief changes as the body holds it. I think about neighborhoods, so places that one returns to and how they trigger memories, but they change, so they hold memory differently as well.

I think the other thing I would want to say, just from having screened it quite a bit in small groups at this point: It doesn’t work with grief quite like we expect movies to. It’s not triumphant, it’s not organized around catharsis necessarily. It doesn’t have music that tells you when to feel bad or good. It doesn’t have the typical beats that cinema is organized around, but I think it has the typical beats that life is organized around, which is this kind of pulsing.

Sometimes grief feels like celebration. Sometimes grief feels like connection. And sometimes it’s very hard to process. Jim died when I was a girl, and I’ve lived with his death longer than he was alive. My grief for him is very different than my grief for Juanita, who died only a few years ago.

We’re in a time organized by grief and mourning. Even if it’s not for the loss of people, it’s for the loss of our democracy and the loss of structures that made sense to us. It lets you come in where you are and acknowledges that’s changing. It might even change over those 70 minutes of the video.

Lauren: You mentioned that iPhones metabolize grief differently than VHS. I’m wondering if you could tell me a little bit more about the mixed media approach to this film, how you decided to combine all these different types of film making, and why that was important for you.

Alex: What it feels like to make media with different technologies, that’s always for me part of thinking of what medium is. A camcorder is actually heavy, and there’s a kind of commitment that to work with heavy equipment demands. iPhones are very light and they are very easy to use and they’re extremely easy to shoot things with and extremely easy to take that footage and put it somewhere else and distribute it and share it and see it.

And therefore, one of the ways that they’re different is that we’re constantly shooting video that is completely expendable. It’s hard to know the difference between the important things you shoot and the not important things you shoot. It’s interchangeable. So that lightness of the iPhone material, the lightness of social media, and I mean that literally but also metaphorically, is part of what I’m thinking about. When Juanita asked me to come shoot her on her deathbed, she had wanted me to shoot her on a camcorder and she didn’t have the power cord, so I took out my iPhone.

But it’s not just the technology. Watching someone die is a cosmic shift. If someone asks you to be part of that, that’s an incredible responsibility and it’s a heavy responsibility. It’s a beautiful responsibility. So, it’s not just that I had the iPhone. I had made this agreement. She had asked me and I didn’t even know why she had asked me initially. It’s in the footage, she tells me, but she’d asked me to do this. I wanted to mark the heaviness of the weight of it, the beauty of it.

This is where the project is about what it means to be in community and collaboration. It’s a very different kind of relationship to media making. It’s activist media making.

In Please Hold, I use video compositing a lot. I think it’s the visual and media language that defines this moment in history. It’s very desktop-looking on purpose and very collage-y. The collage holds VHS and iPhone videos next to each other, or digital video and iPhone video and then text on top of that. I’m interested in that collage aesthetic that flattens the discrete technologies. Then I work very hard to keep reminding you that they are discrete technologies.

In every shot of video, I tell you what kind of camera it was shot on and when it was shot because, again, I think that the computer screen that you and I are looking at right now equalizes, flattens things. I’m both interested in seeing that as an aesthetic and thinking about what it does.

The film is about grief, it’s about memory, but it’s also about communication. It’s also about me talking to people who have died and me talking about people who are very much alive, who I’m in activist community with. I’m trying to think visually about the sort of flatness of the screen and the depth of the interaction. That’s what that compositing does to me. But that’s also having the Zoom interviews where you see two people, like we’re doing right now, as opposed to a more traditional talking head. You’re constantly aware of the depth, the third dimension of the screen, because the listener produces that.

Lauren: I wanted to ask you about the Zoom interviews. How did you decide to incorporate these conversations with folks that you’re in activist community with?

Alex: Video Remains is the video that I made with my footage from my friend Jim’s and my one hour on the beach together in the last year of his life. It took me a long time to make that video and it’s very important to me. I think it has a place within the history of AIDS media that is a critical place.

This video [Please Hold] is referring to it in many ways and thinking about technological shifts. In Video Remains, I talked to my fellow AIDS activists, they were all women and lesbians, on the phone. That’s cut into the long take footage that Jim had asked that I shoot of him on the beach when he was telling the story of his life.

Fast forward to now, with these new technologies, I’m like, we wouldn’t talk on the phone, we would talk on Zoom. It parallels that method of sharing space and knowledge with collaborators and my activist community. The video that I made now is thinking about how COVID, and our experiences during lockdown in particular, rejiggered our expectations and relationships to communications technology.

It’s a recognition that that’s a new form of media making. I’m an activist media maker. I make things for nothing. I shoot them with whatever is at hand. I distribute them that way. And Zoom is an amazing, inexpensive form of technology to interview people. The interviews look and sound pretty good.

I am also trying to think about these different formats of connection, what it is to live together in a place, what it is to use a phone or Zoom, what it is to be in a place or be with a person who has been, that was recorded and you revisit.

The film really believes that we can continue to collaborate with the people we love after they die, or that I can, because I’m still asking the questions and working on projects and trying to make the changes that were very important to both me and Jim. I’m still committed. I need their voices. I need who they were to me and what they know and what we could make together. I can still use that, even when they’re no longer here, because we made these videos together. I’m so lucky.

Clockwise: James Robert Lamb, Pato Hebert, Alexandra Juhasz, Juanita Mohammed Szczepanski (built from “Video Remains,” Alexandra Juhasz, 2005, Zoom interviews, 2023, and “I Want to Leave a Legacy,” Juanita Mohammed Szczepanski, 2022, iPhone).

Lauren: How else has this work impacted your life?

Alex: Right now I’m starting DIY and activist distribution, which I’m doing by myself. I’m trying to get it out in the world, but trying to get out in the world under the terms that seem right for me.

In the book that I wrote with Ted Kerr, [we write about] the idea of “trigger films” or “trigger videos,” [videos] from the early part of the AIDS crisis that you would show, stop the video in the middle of a scene, and then people would talk about it. We use the word “trigger” now differently. We talk about this in the book, but both uses of “trigger” are about setting terms for healthy conversation.

I think that Please Hold is also a trigger film. I think that what it’s best for is to spark conversation. And I think that, like so much on the internet, it shouldn’t be watched alone by yourself, with two other things on your screen. That’s probably true of a lot of art films. But I’m saying, it’s not just any art film. It’s a film that holds the traces of two people who died, who ask to be seen. It takes a lot from us as contemporary media viewers to change the way we’ve been taught to watch to be more human and to be more caring and to be more present.

I’ve tried to put a tiny scrim between getting the film for free, which I’m letting you do, and watching it with more care. You have to fill out a little form that says, “I’m going to watch it by myself. I’m going to watch it with some people. I’m going to set up a screening.” Then I send you the link. I don’t know if that’s going to work. But I’ve never really cared how many people see things that I make. I care about the context in which things are seen. That’s true of activist media more generally.

I want that context to be respectful and contemplative and interpersonal and give people space to talk afterwards, which so little viewing does now, especially when things are digital. The main thing I’m doing is trying to move it in the world and have conversations where I can be present with other people with what it brings up.

Lauren: That’s beautiful. That’s such an interesting way to experiment with distribution. I love that. As you’re talking about care, I was even thinking about your film We Care that I’ve showed in class a number of times, that is also about care and dying, so I can see those through lines in your work.

Alex: I think that the norms of dominant cinema push to the edge a lot of the things that actually can and do happen when we consume media together. One of those is the idea of care. That’s something you could build around screenings.

I think people do it, but you need to think about, in what conditions do you do that? Because the consumption of media now that we’re all on our laptops, it’s just violent and hurtful. It doesn’t matter if you’re consuming something you like. It doesn’t make you feel good. It’s the opposite of care, even if you’re watching something beautiful. The extratextual conditions of making and screening activist media are as important as the piece of media itself. And that’s what I’m doing by building out my own distribution.

The reason I made this was to talk to people about AIDS, and to talk to people about HIV, and to talk to people about memory, and to talk to people about dying, and to talk to people about community, and to talk to people about all the ways we love each other and all the ways we help each other, and how beautiful it is to be in community. I want to have that conversation every time it’s screened. I hope other people will talk to each other about those things. That’s why we make art, certainly activist art.

What we want from activist media is that you’re transformed, that you feel a transformation and you feel that you can interact, not just consume.

Lauren: That brings me to another question I wanted to ask. Can you tell me about the title Please Hold?

Alex: The first shot of the film — well it’s not the first shot anymore, it’s deeper into the film now — is me riding up an escalator at the Delansancy/Essex Street stop on the Lower East Side, the F train. It’s a long take, and I go up the staircase. I think it’s beautiful. It’s so dirty, and makes all this noise. It’s so industrial and of this other era and it evokes that neighborhood in New York City.

As you get to the top, you see this boy wearing this powder blue sweatshirt, and he’s on his phone, and he’s almost dancing. It’s like choreography. But if you look above him, there’s a LED sign and it’s saying, “Please hold the handrail.”

I was deep into editing the film and I’m like, “Oh my god, that sign says please hold!” If you listen to the film, I talk about holding all the time. The word “hold” is used in it over and over and over again. And I’ve already talked about it like that with you. I’m holding these memories, I’m holding these tapes. A lot of the people in the film help me think about holding things together.

My friend Ted [Kerr] talks about holding a sweatshirt of Jim’s that I had given him. That’s a way for Jim to stay with us, we hold it together. And then holding the Parkside, which is a gay bar, queer bar, and you’re holding that space. Jih-Fei [one of the interviewees in the film] talks about holding spaces when nobody will let you, which is very much about what we’re in right now. What it means to hold the space of trans identity or gender non-conforming identity or a bathroom that’s become dangerous territory, and they say you can’t use it, and you hold it. That is something that political people do.

The Parkside also holds ghosts, it holds porn magazines. So holding just constantly emerged in the process. But then the title was given to me by the Lower East Side. And of course, “please hold” is also what someone says on the phone in a not nice way, so it has that register as well. It makes you wait when you’re not ready to wait.

The film is also about walking as a technology of memory, how the world presents information to you when you’re ready to receive it. Walking can wake you up to take in input that you wouldn’t see. So the fact that the title is there because I’m walking in the neighborhood is very much an idea of the film that the world can help you too, if your body is open.

I’ve had the great luck to stay alive this whole time and my body is so different. There’s a lot of seeing me young and seeing me now in the split screens. There’s a lot seeing Juanita young and seeing Juanita now in split screens. There’s not that of Jim because I only have the images from that one period of his life and he didn’t get to live to be older.

My body at this age, I just turned 60, takes in the world differently than my body did when I was 29. And in a lot of the footage that you see, I’m 29. I actually understand the world differently through this technology. I think in a sexist world in particular, I say this as a cisgender woman, I think I understand the world much better in this body than I did when I was 29, and that’s why there’s so much ageism, especially against women, because people don’t want women to be smart in that way. They want to tell us these bodies are not useful tools and not intelligent receptacles. Quite the opposite, as we age, our bodies become smarter if we’re lucky, or wiser, or deeper, or more sophisticated. I do not need to be the 29 old girl that I see there. I’m very glad that I’m not.

Lauren: Thanks for sharing that. Is there anything else that you want to share, or that you want Autostraddle readers to know?

Alex: One of the things that I love about this movie is how queer it is. It is my definition of queer, everyone can have their own. What I love about it is that the characters that you meet are every kind of different. They’re every kind of deviant. They’re every kind of edge. And sure, you can say they’re lesbian, trans, gay, Jewish, Black, Asian, young, old.

But the movie is not committed to a particular slice of the queer world. It’s expansive about how queer love and queer community, queer analysis, queer ways of living and family and being political and caring and making relationships of care. That has been everything to me. And that’s true in my nuclear family, lesbian family, that’s very extended into other parental roles. It’s true in my queer romance with Jim. We lived together for many years.

It’s true in my very queer friendship with Juanita that crossed race and class and brought us together in an overt analysis that came from the celebration of gay and lesbian life and trans life. So I want the readers of Autostraddle to behold a feminist queerness that is my community and is me. I love being in this community. I love being seen by this community.

I love speaking to this community. I love the way the film stretches that inclusion and also its limits. That’s the queer lifeworld that I draw from in that video.

Lauren: Since it has been a couple months since Trump’s inauguration, I’m wondering how you feel about the film coming out right now and what you feel the film has to say about this contemporary moment.

Alex: I am as confused and hurt and angry and afraid and uncertain as anybody. I don’t have any answers right now at all. Many of the things that I thought were answers don’t seem to be. That’s super scary.

But what I just said to you about queer community and queer love that is connected to activism — not just who you have sex with or who you want to go to a party with, although that’s part of it, but connected to working together to make the world better for the most disenfranchised, the people who are the most weak and the most threatened at any particular moment. And sometimes, like right now, that is trans people, right now that is people in our world with HIV and AIDS who are truly about to be decimated by the end of PEPFAR and threats to Americans’ access to free medication.

Queer love and queer community that’s organized around wanting to help each other and help the most disenfranchised — that is always a goodness. The minutes you can spend in it or the hours you can spend in it are worldbuilding. They’re being in the world that we want and we deserve and we can make, and even if we can’t right now respond to the huge threats, and even as they will be endangering people we love, or killing people. Killing people in Africa via [the end of] PEPFAR, killing people in Gaza, killing people in the Ukraine, killing people in the Congo, I could go on.

We as humans can make little reprieves, little pockets, little sparks of beauty and dignity and decency. And queer people have always done that. We’ve had to. And so watching the film together, talking together, that’s just an example of knowing that we can make moments of power. It might not be big. We talked about how how many people watch something is not a register that matters to me. Smallness is often what you need to have deep impact. We can be in community and learn with each other. And so we will do that. We can do that. We are doing that. We have done that. And it might not change the badness, but it is itself a goodness.

Lauren Herold: Thank you. That’s a beautiful way to end this conversation and also I feel like I needed to hear that today. So, thank you for saying that.

Alex: But see, this conversation is that, Lauren. It’s like, I see you. I heard what was happening in your life. Thank you for listening to me so much about my film. It’s simple, but we can and should and have to do that for each other all the time right now.

Testing a comment