I.

When I was seven, I cut myself shaving. I remember when I did it, the sharp sting of the blade slicing my cheek, a stripe of pink flesh and red blood from cheekbone to chin. I didn’t scream. I dropped my father’s razor – one of those cheap, white plastic Bics that come in a pack of six – into the sink; the hollow clack and splatter of red against porcelain shocked me into action. I fumbled for tissue, pulling it frantically from the roll, jamming the two-ply to my face.

When my mother came into the bathroom, she grabbed me by my thin, narrow shoulders, pulled at the tissue, some of it already sticking to my cheek, the cut stinging anew as she cleared clot and cotton from the wound. She cleaned me up, blowing mama-breath on the cut after she dabbed it with peroxide. She fastened a square of gauze to my face using small strips of medical tape from the first aid kit we kept on the bottom shelf of the linen closet.

My mother and I

All those details are clear to me though what happened after my mother walked me to my room is difficult to recall. I do know that afternoon was the first and last time I tried to shave my face.

I asked my mother if she remembers what I’ve since referred to as “the shaving incident,” and she said she did. She recounted finding me in the bathroom, blood all over the sink, tissue sticking to my face in pink strips, balls, and patches. She told me how, after bandaging my face and walking me to my room, she went into the bathroom, cleaned up my blood, and threw away my father’s razor. Then, she promptly returned to my room to beat my ass.

When I asked her why she spanked me – a detail I don’t remember, probably because as a lying, rambunctious, trouble-making child, my many, many ass whoopins’ all kinda blur together in my memory – she said, clear and matter-of-fact, “For playing with razors.”

My Dad and I

The “shaving incident” left me with a one-and-a-half inch scar on my face, and I think about it more often than I like to admit. I look in the mirror at my face, concerned about these new and annoying instances of adult acne, then I turn to consider the conspicuously increasing amount of hair growing from this one spot on my chin. For a split second, I contemplate shaving it. I dismiss the idea as soon as it forms and without thinking, my eyes flash across to my right cheek; I consider the scar and follow the deep line into memory.

The scar

I know exactly why I did it. Attempted to shave my face. I wanted to be like my dad. I used to stand in the doorway to the bathroom and watch him shave. He was always so cool with it. He sported different styles and shapes – Fu Manchu to goatee, Van Dyke to Balbo, pork chops to chin strips. No matter what facial hair design he chose, it always seemed to complete his look. During the week, my dad hauled gas cylinders marked flammable and hazardous onto big rigs and loading docks. His beard and moustache all but an after-thought against his hard hat and goggles, dirt-smudged t-shirts and grimy jeans. But on the weekends? My pops got clean – wide collared shirts, sharply pressed pants, and heavy leather belts that matched his tasseled loafers or gleaming wingtips. He kept it classic, smooth. He ran fools off pool tables and bought rounds for old friends and new friends – my pops ain’t ever really met a stranger. He carried his cash in a thick wad and drove leaning to the right while coasting with one hand on the steering wheel.

To my child sensibilities, before I discovered how many times a pool game had cost us our rent and before I found out that we couldn’t keep a car because my drunk-driving father would crash them up within months, my father was the slickest of the slick and cooler than a polar bear’s toenails. I wanted to be just like him. He was that dude.

I’d cry if I couldn’t sit behind him in the car while he drove, back-passenger, driver’s side, where I would use the Frisbee we kept in the car for impromptu park stops as a steering wheel and pretend to drive. I’d put on my father’s leather wing tips and loafers, slip one of his ties over my head, and even try on his blazers from the couple of suits he owned for the rare times he joined us at church. And one day, I even decided to shave like him.

This wasn’t strange to me. This desire to be like my dad. Not until one Christmas Eve, the same year as the “shaving incident,” when my older sister told me that Santa was going to come to our room that night and turn me into a boy. She said this into the darkness, and I can still hear her voice floating up to me from her bottom bunk while I stared in fear at the ceiling above me, “You gonna wake up Christmas morning as a boy.”

I tried my best to stay awake that night. My mother had already told me Santa doesn’t come until all the kids are asleep. I figured that if I could stay awake, Santa wouldn’t come change me. If I didn’t go to sleep, I could still be me.

II.

Growing up, there was nothing like summer in Milwaukee. Nothing like the freedom of running through sprinklers or playing in the creek at Dineen Park, cool water splashing up your ashy shins and scuffed up knees, warm sun rays kissing your bare shoulders, your only concern keeping an ear out for your name to be called because the hot dogs are done. Nothing like lying next to your father on a stretch of fuzzy green blanket spread across the grass, both of you in cut-off denim shorts and no shirt, both of you staring up at the perfect puffs of clouds moving slow but steady against the blue of limitless possibility.

I rarely get that Milwaukee-summer feeling any more, even when I visit my hometown every late July. Those times are gone now, that feeling difficult to reproduce. I try it though, and even come close.

When I’m able, I enjoy visiting Haulover Beach. The beach is in North Miami, a stretch of sand and ocean hidden from the street by a fifteen foot screen of thick green bushes and wide palm fronds. The walk from the parking lot across the street to the main entrance, a nondescript break in the wall of green, is a fairly short one, and the people passing to and from the beach share quick glances and knowing smiles. Before you even reach the first sign alerting you that clothing is optional and that you may encounter nude bathers, you already feel like you’re in on some shared secret, some exclusive club of people searching for a different type of liberation.

At the nude beach

I go to Haulover Beach with friends, women who, like me, love the embrace of summer sun and ocean breeze on their bare skin. Women who, like me, want a chance to recapture something – something like the freedom to just be, to just for a moment, live in our skin unabashedly and unafraid.

The nude beach is separated, a “mixed” side and a gay side. My friends and I always go to the gay side. The mixed side has a lot of hetero couples and too many men with hungry, intrusive eyes. Men who stare at your breasts to say hello and lick their lips as they dip a shaming glance to your pubes. Being naked does not mean open season on my pussy. What a woman wears or, in this case, does not wear, is never an invitation to be violated or accosted by eyes, hands, or anything else. Nothing is more illustrative of America’s Puritan-bred sexual repression like walking through the mixed side of Haulover Beach to get to the gay side.

The gay side of the beach, for women, has fewer eyes. The gay side is dominated by men, all shapes, sizes, colors, and lengths. The men are more concerned with each other than the rising tide or approaching clouds, and when they do acknowledge me and my friends it’s in passing and many times friendly, especially if they’re Black. Black men on the gay nude beach offer a smile and special nod, an appreciation almost, for being adventurous and open in ways commonly reserved for whites. On the gay side, a naked woman can sit mostly unbothered. I can sun-bathe and read, swim and watch cruise ships in the distance.

Once my friends and I have survived the ogling on the way to the gay side and finally settle on a spot, we situate our snacks, books, towels, and blanket, then I head directly for the water. I remember saying to my friend once that swimming naked feels like a memory, a reconstruction of our first memory even – naked, in water, a return to the womb. She laughed at me, per usual, then added, “Is that why you like baths so much?”

Could be.

In the water, I swim a little, pushing against the waves, but mostly I float on my back, my bare breasts up, my arms and legs out. I stare up at the sky like I used to in the park. I daydream. Any number of random thoughts and hopes, dreams and desires, playing out against the backdrop of inviting, encouraging blue. The images are rapid fire, mostly about the future, from the consequential to the mundane – love, the books I will write, friendship, the trips I will take, tacos. I leave the water, feeling powerful, rejuvenated, affirmed, and when I lay down on my towel to air dry, the sun kissing my bare shoulders and ocean breeze whispering across my nipples, I think about what my father always said about dreams: “if you want something, you got to get out there and do it. Don’t nothing come to sleepers but a dream.” Unencumbered by clothes and life and worry, I say “I can do this” under my breath. And “This” is whatever the hell I want.

I really, really wish I could spend more time naked or at least topless. I saw a social media post once that asked women, “If you could be a man for a day, what would you do?” The responses were all over the place, a lot of sex and peeing standing up. The most popular answer was: “I’d spend the entire day topless.” That was my answer, too. I would pump gas, go to the beach, walk around the park, wash my car, sit on the porch, take a bike ride downtown, all without a shirt. It seems simple, but it’s a liberation that’s foreign to many of us, a simple freedom women are denied, and I hate it.

When I was nine years old, my mother, my sisters, and I moved into a townhouse on Milwaukee’s northwest side. We moved a lot, so it wasn’t really a big deal to me, except for one difference. For the first time, my father wasn’t with us. He was in jail, too many DUIs and a couple of other things I was too young to know about at the time.

Moving day was exciting and busy. My mother, sisters, my uncle, my uncle’s friend, and I made up the moving crew. Music blared from a boom box on the cement step that made up the back porch, and my uncle’s friend had parked the U-haul truck on the grass to shorten the distance from truck bed to back door. It was hot, and my uncle and his friend had taken off their shirts as they carried furniture from the truck to the house. My sisters and mother worked mostly in the house, organizing boxes. Bony but strong, I hefted boxes against my flat, bare chest, carrying housewares, clothes, and toys from the U-haul to the back door, then pushing the boxes across the laminate kitchen floor onto the carpet of the dining room then against the wall for my sisters and mother to sort and unpack.

I had made quite a few trips before my mother stopped and noticed that I, just like my uncle and his friend, had gone topless. She yanked me by my arm and held me tightly by the shoulders, shaking me, her nails digging into my skin: “Put your shirt back on, girl!” In my memory, she screamed it. Her eyes on fire. Everyone’s eyes on me. My older sister smirking. My younger sister curious. My uncle and his friend amused. I went tingly and hot with embarrassment and shame. I cried.

It was the first and only time I can remember wishing I wasn’t a girl. If I weren’t a girl, I wouldn’t have been crying. If I weren’t a girl, I wouldn’t have had to wear a shirt.

III.

My daddy’s nickname for me is “Pretty.” When I call him, even to this day, he says, “Hey, Pretty.” Even when I didn’t feel pretty, which was most of my teenage and young adult life, my pops calling me “pretty” like it was my name always made me smile. I remember when I came out to him. We were driving down Central Avenue in St. Petersburg, Florida on our way to have an early dinner and shoot a few games of pool. I told him I was gay, and he told me a story about a drag queen he used to know back in Milwaukee. Then he said, “Just as long as you’re happy, Pretty.”

Happy? At the time, a whirlwind period of coming out to family and friends in 2006, I wasn’t sure that I was. Relieved, maybe, and closer to liberated for sure, but happy? Not quite. And “pretty?” I didn’t feel too much of that either, and it had a lot to do with the way I dressed.

I prefer not to wear dresses. I don’t want to wear a skirt or carry a purse. Nearly a solid year after coming out, when I finally felt comfortable and strong enough to wear only what I liked, I gave away all the dresses, stilettos, and purses I’d worn to please other people. And for a long while, I dressed like a teenage boy.

I was in graduate school, working three jobs and drinking too much, writing furiously and trying to figure shit out – me, my life, my place in this world. I was consistently broke, so no one noticed or cared that I wore a uniform of t-shirts and jeans. Because Chicago was cold – even colder than I remembered the Midwest to be – my sweatshirts and chunky cable-knit sweaters drew no attention either. On my feet? Sneakers, Converse and Adidas mostly, and a pair of steel-toe boots once that lake-effect snow hit. A friend of my mother’s, who at one-time was on the path to becoming my step-father, got me a men’s Carhartt work coat to go toe-to-toe with the Hawk, Chicago’s fierce, winter wind. It kept me beyond warm, and I loved it.

Unfortunately, the ease with which I approached my appearance melted away when I returned to Florida in 2009. With graduate school complete, an MFA earned, and my bank account in the red, I needed to get a job. Quickly.

My first job out of graduate school was at the YMCA, tutoring third grade. I wore a red Polo shirt, the Y’s logo across the breast, with tan or navy khaki pants. When I upgraded from tutoring to teaching adjunct at two local colleges, I revisited my wardrobe. I could not begin my college teaching career dressed like a teenage boy.

Three pairs of slacks and five dress shirts. Thirty dollars from my mother’s favorite thrift store in St. Petersburg. On my way up to the register, I stopped at a display of ties. Skinny solid-color ties from the sixties and short, wide-bottomed ties from the forties. Smooth silk ties from the thirties and busy shapes and patterns that screamed with the electricity of the eighties. I held my shirts up to a few, and found a plaid blue, green, and black one that matched all three shirts perfectly. Eighty-five cents. I stepped to the cashier, hoping she’d ring up all my stuff before my mother met me at the counter.

Tie collection

Later, I hesitantly showed my mother my tie, prepared for raised eyebrows and twisted lips. “I’m just glad you ain’t one of them real manly ones,” my mother had said when I came out to her. She surprised me with a smile, taking the tie between her fingers and considering the pattern. “You know, I used to wear ties.” She showed me how to tie a four-in-hand knot and a half-Windsor. My mama is always surprising me like that, her coolness unexpected, her understanding unanticipated. I looked at her in awe; she looked at me like “you betta ask somebody.”

The murrell

Shoes, however, proved more of an issue. Fitted with simple outfits of ties, button-ups, and slacks, I needed some nice shoes to complete my “professor” look. I had gone to DSW alone. It seemed easier that way.

Sweaty palms. Dry throat. Heart a Timbaland beat. Since when did walking the aisles of the Discount Shoe Warehouse elicit such anxiety?

The Prince Albert

I walked around for nearly thirty minutes looking at ugly ass pumps and biscuit toe loafers with wedge heels before finding the courage to walk over to the men’s section. Seized by an irrational fear and self-consciousness while walking through the rows of leather and canvas shoes, I chickened out and settled on two pairs of Adidas, one plain and brown, the other gray and black.

My sisters said I looked cute dressed like Ellen.

My first year teaching went well, and my dean recommended I apply for a newly vacant full-time position. The interview process included a teaching presentation and three rounds of interviews, the finale being a session that would put me on one side of a long, mahogany meeting table with the college president, vice presidents, and department dean on the other.

My mama said, “You better not wear tennis shoes to that job interview.”

I returned to DSW. Nearly forty-five minutes passed before I finally made my way to the men’s section. Pushing through anxiety and breathing slow and even against a swell of self-consciousness in my chest, I found a pair I liked. Two pair. Three. I decided on a gray pair of oxfords and a pair of brown loafers.

Although pleased with my choices and the discount price – both pairs for a little over a hundred dollars was a lick – I barely made eye contact with the cashier and fought the urge to explain my purchase as a gift for my father, who, when I wore oxfords later, would say jokingly while lighting a cigarette, “you need to give them to me.”

I got the job. To celebrate, I went to my favorite gay bar. My face bright and proud, the little bit of make-up I wore that day – eyeliner and mascara at the encouragement of my mother and sisters – still holding up, and dressed in my work clothes – slacks, button down, tie, and loafers. I met up with a few old friends and new friends, buying shots and cocktails, lifting my Maker’s to cheer the good fortune bestowed by the universe and the good judgment exercised by the college. Every song the DJ played was my jam and every drag performance, each sultry wind of hips and provocative wink, was directed at me. For the first time in what felt like a long time, I had some answers. I knew who I was and where I was going. I felt like myself, like I finally found myself.

In the computer lab

At work lecturing

On a trip to the bar from the pool table, where I played horribly but happily, a woman touched my arm and pulled me closer to her. She smelled like rose water and Black and Milds. She whispered in my ear, her lips grazing my cheek. “You look real handsome.”

My heart sank. I forced a smile and pulled my arm away from her. A bubble of whiskey flavored stomach acid burst in the back of my throat, burning my vocal chords into silence. I swallowed and nodded something like a ‘Thank You’ then turned to head toward the bathroom instead of the bar. Inside the tight, over-perfumed women’s restroom, I stared at myself in the mirror. I fingered the Windsor knot of my tie and ran my hands over my breasts, full and round against the blue stripes of my white dress shirt. I leaned forward against the sink and looked into my own face: the slight eyeliner on my top and lower lids, the brush of mascara to pump up my lashes, the gloss of my lips. Then, my scar.

Double windsor

IV.

The word ‘handsome’ has its etymology in English. Handsom, as it was originally spelled, means “easy to handle.” Additionally, when used to mean attractive or good-looking, is actually genderless. You could be a handsome man, or a handsome woman; you can write handsomely or carry a handsome bag. Attractive is attractive. Easy on the eyes is easy on the eyes. I’m not sure how the word became so closely tied to the masculine. I don’t even know why it bothers me so much to be called handsome.

No. That’s not true.

When I gave up my skirts and dresses, when I stopped carrying a purse and started carrying a wallet, nearly everyone around me behaved like I had forfeited my femininity, rejected my womanhood. Except, I never felt that way. I’ve always felt like a woman, always identified as a girl, from the time I shaved my face to my first pair of men’s shoes. The pressures, as deeply-rooted and overwhelming as they felt, were all from outside. A push to be a certain way, to fit a certain understanding, to gain a certain acceptance. Walking in my truth as a lesbian allowed me to burst through ill-fitting labels in one way, but then, without knowing how or why, I found myself forced into other labels when all I was trying to do was be myself.

Just this year, I was asked to be on a conference panel and was introduced to the term, “masculine of center.” The term is defined on butchvoices.com as follows: “Masculine of center (MoC) is a term, coined by B. Cole of the Brown Boi Project, that recognizes the breadth and depth of identity for lesbian/queer/womyn who tilt toward the masculine side of the gender scale.” The panel, centered on that term, invited lesbian women writers to talk about their work and their lives as MoC bois, butches, and studs. I agreed to be on the panel, thinking that of all the descriptions of the kind of woman I was, MoC seemed like the best fit.

The panel wasn’t selected to present at the conference and in passing, I heard the panel referred to as “a stud writer panel.” It hit me the same way that woman calling me handsome did.

I don’t identify as a stud. I’ve never used the term ‘boi’ to describe myself and even though I found it endearing when a beautiful, femme-identified lesbian used to call me “Baby Butch” when I first came out. All this terminology feels more like another box that I, because I’m a lesbian who doesn’t wear dresses or make-up, have to fit into or face the quizzical eyebrow raises if I wear a low-cut top or a pair of tight jeans. How did I end up going from one identity crisis to another when I was finally supposed to be certain about who I am?

I identify as a Black, lesbian woman, and outside of that, I ain’t got no answers. I don’t know enough about gender or sexual politics to break down the differences between gender expression, gender identity, and assigned gender. I don’t know what social pathologies and personal experiences contributed to how I present myself and how I feel. Thinking about it all every time I stand in front of my closet or stare at my face, the scars of memory and exhaustion of searching marking my body, is enough to make me swear off clothes – run off to join a nudist colony or spend the rest of my life soaking in the bathtub. But, something happened recently that showed me that I’m over-thinking this whole thing.

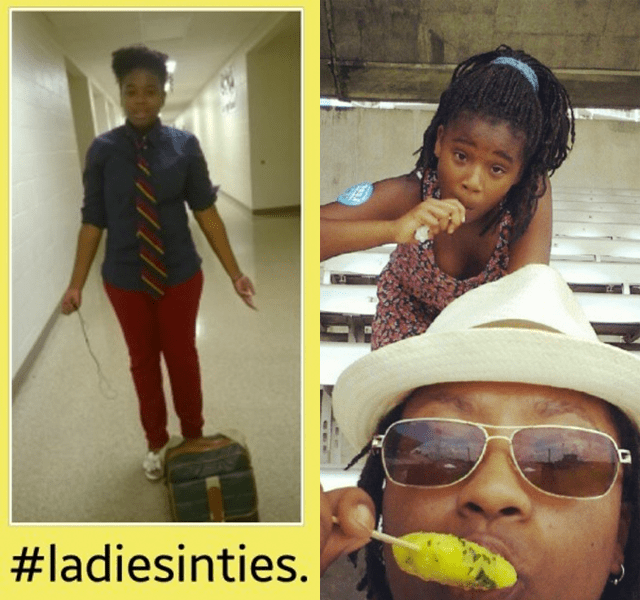

My niece and I. Popsicle twins.

My fifteen-year-old niece sent a photo to my phone. She stood in an empty school hallway, shiny floors and dull walls with carefully placed posters. With her hands on her hips and a little head-tilt, she smiled into the camera, her pride and youthful energy bursting through the screen. She wore red, skinny jeans hugging hips I’m not ready to acknowledge, a form-fitting button up shirt with a four-in-hand-knotted, college-striped tie loose around her neck. There was no message, just a hashtag: #LadiesInTies.

The picture rendered all the labels and terms irrelevant. We wear what we want to wear. We emulate who and what we want. We are who we say we are, what we say we are.

I am a Black, lesbian woman who likes to wear ties and swim naked, who carries a wallet instead of a purse and loves to be held, who buys men’s shoes and women’s pants, a woman who owns her scars and lights up inside when her father calls her “pretty,” a woman who can’t wait to teach her niece the half- and full-Windsor.

oh my heart. this was everything. thank you so so so much!

I have such a deep, deep, profound love for this.

I don’t even have the words to describe.

Wow.

Thank you for writing it and for sharing it.

<4

This was beautiful, both the writing, and the sentiments expressed.

thank you for this.

Ah you are a remarkable writer. I was so siked to see in your bio that you have books out…can’t wait to get my hands on them. And so pumped to see more of you on here in the future. Thanks for writing this :)))

It never gets old to learn how someone has taken up residence in their most honest self…aaahhhh, so good to hear! Thank you Sheree, I thoroughly enjoyed your writing.

<3

Wow.

Didn’t know I needed it until I read it.

This was so good. I loved that last little bit at the end.

Thanks for sharing your story… Brought me back to some of my own firsts. I am in my 50’s – from Tom boy as a kid to (soft) Butch lesbian from when I came out @ 18. I remember wearing button downs & ties, wing tips and chinos out to clubs in my wayward youth – All in some kind of journey, coming home to myself – seeing myself through occasional appreciative glances from some femme along the way.

It is odd, somehow, that I have cycled through so many decades, off & on trying to present more feminine, only to wind up back where I was before with only some adjustments (I haven’t worn a tie in years).

Anyway, thanks – I remember trying to get up the nerve to buy men’s clothes, then more than that, wearing them, trying to keep my head up & my gaze steady.

I know now, there has always been something with me that is more than just a feeling of being a grown up Tom boy. We used to call it ‘gender – bending’ and ourselves ‘gender – benders’…So much respect and love for the trailblazers, making life for us a bit easier, with each generation of queers.

Looking forward to reading more of your work.

“All in some kind of journey, coming home to myself.” Yes!

Thank you for putting into words how I feel.

It hasn’t even been a year for me yet, so I’m still finding the words, but a lot of this resonated with me. Thank you for writing and sharing your experiences.

Despite getting lost in the whirlwind of new words, I’m pretty sure I still identify as a woman; I’ve always felt like one… But I’m still doing the work to really understand what that means to me. I also really like feeling beautiful, attractive, pretty… And I also sport a barber cut, wear pants, oxfords, button ups and blazers more days than not. I used to be all about makeup, dresses and killer heels, because I craved the attention, the desire and the acceptance. Shedding the clothes and appearance that I wore to feel like I could be loved, and learning to accept and love myself, for myself, I’m now happier with my body and how I dress than I’ve ever been.

Maybe because I’m 5’10 as well, but I get called “sir” a lot. They’re either genuinely making a mistake, because they thought I was a man, or think they’re being respectful… Calling me by what they assume to be my preferred gender identity. They’re not though. It’s not respectful to assume. Every instance of the greeting, “sir” feels like a sharp jab. It shocks me and hurts me.

I didn’t give up my femininity, my woman-ness, my female-ness when I came out. I am a woman, a masculine of Center, queer Woman.

This part: “Despite getting lost in the whirlwind of new words, I’m pretty sure I still identify as a woman; I’ve always felt like one… But I’m still doing the work to really understand what that means to me.” Exactly!

Posting that response publicly was terrifying… difficult to admit because I want to assertively say, ” I AM.” when I don’t know for sure yet, so… thank you, for acknowledging my response and making me feel welcome.

Loved this, thank you

This is so wonderful – I hope to read more by you here. Thank you!

This was WONDERFUL. Thank you.

Wonderful piece, I can relate

I loved this !!

yo this was some real powerful stuff. it resonated with me a lot <3

Our love of menswear and women aside, our life experiences couldn’t have been polar opposite – yet Greer still manages to make me totally identify with her.

*more* polar opposite

This was so good to read. Thank you.

What a beautiful, moving piece. Thank you for sharing it.

Thank you. This resonates with me so strongly.

Thank you. I feel like I’m going to come back to this text again and again.

The whole time I was reading this I kept thinking, me too, me too. I remember trying on my dad’s ties and pretending to shave (I wasn’t ever brave enough to pick up a real razor). I’ve had the same confused reaction to being called sir or handsome. I just feel all of this so much. Thank you for sharing it.

It’s weird isn’t it? Because it’s like, should I feel some kind of way? I mean, it is a compliment, but… do I get to say “but”? Is that allowed?

This was so good, thank you for sharing.

so beautifully written. thank you.

<3

This is the best thing I’ve read all year.

This is relevant and important and so, so beautiful. Thank you.

This was lovely. Please write more pieces for Autostraddle!

I second that.

This is a big deep breathe on a Saturday morning. Thank you.

So beautiful. Thank you.

So good! Thank you, Sheree!

This was really lovely.

This is a really lovely piece–so lucid, hitting hard at sudden moments. Thank you for sharing this with us.

Beautiful.

Thank you to everyone who took the time to read this and to those of you who found it worthy to comment and share. I loved seeing your responses and reactions to the work. It’s like we are all in on this shared secret, this shared existence through exchanging our stories and experiences. It’s what I love so much about writing — what I love so much about sites like Autostraddle — it’s a chance for us to connect, a chance to feel less alone in what we think is our own private anguish and confusion, our own private struggles.

We outchea. All day. Thank you all. So very much. I can’t think of a warmer, more inspiring welcome to what I hope to be a strong relationship with a great publication. Much love.

I loved your post so so so much. I hope you write more and share it with us all.