The first alcoholic drink I ever had was a rum and Coke, and I was disgusted. It wasn’t the rum that was the problem; it was the Coke. Mormons typically don’t drink caffeinated drinks, so I wasn’t accustomed to the taste of Coke. It tasted bad, like something a sinner would drink, and it was completely ruining the experience of my first mixed drink. My friends made me a rum and fruit punch instead, and I spent the rest of the night enjoying the spicy taste of rum blended with sugar and red dye #40.

Strong reactions to illicit sodas—just one of the many remnants of my history with The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, also known as the Mormon Church. You wouldn’t suspect my religious past from interacting with me. I’ve assimilated to secularism quite nicely. But say the word “Mormon” and I’ll snap to attention, like a sleeper agent who’s just heard her activation phrase. “What did you just say about Mormons? Sorry, it’s just that I used to be…”

There’s a saying within the Mormon community that goes, “You can leave the Church, but you can’t leave it alone.” The line is from a 1989 talk by church authority Glenn L. Pace, who goes on to explain:

“The basic reason for this is simple. Once someone has received a witness of the Spirit and accepted it, he leaves neutral ground. One loses his testimony only by listening to the promptings of the evil one, and Satan’s goal is not complete when a person leaves the Church, but when he comes out in open rebellion against it.”

If God is a woman, then maybe Satan is too. She, that wily serpent, began teasing me with lesbian thoughts when I was a senior in high school. By my sophomore year of college I was thoroughly seduced. Now, here I am writing about Mormonism on the unholy site that is Autostraddle. Just call me Satan’s mouthpiece.

Maybe my frequent musings on Mormonism are “open rebellion,” or maybe it’s just the result of constantly being reminded that the Church was a fundamental (no pun intended) part of my life for almost two decades.

The Church influenced minor aspects of my life, like who I rooted for during American Idol Season 7. (I was Team David Cook, but it felt like treason.) Then, there are the major things that the Church affected, like how I viewed my sexuality. Some misguided people will tell you that being gay is a mental illness. It was Mormon doctrine for the longest time, although they no longer teach this. I don’t know how long I’ve been “sick,” but I was asymptomatic for most of my life. I was a devout Mormon, so any flickerings of gay feelings I might have had were snuffed out by my piousness.

Around the time that I was applying to college, however, things started getting a little weird. For example, there was a period of time when I had an unexplainable obsession with Bryn Mawr, a women’s college. Senior year of high school was a tumultuous time, so any gay angst was overshadowed by other issues, such as:

What school should I attend?

What should I choose as my college major?

Forget choosing a major, would I even be able to afford college?

I desperately wanted some guidance. Enter the patriarchy.

A Mormon patriarch is an old man who is called of God and is sensitive to guidance from the Spirit. The patriarch has one responsibility, and that responsibility is to give patriarchal blessings. Patriarchal blessings are special blessings given to worthy Church members and contain personalized counsel from the Lord.

A patriarchal blessing is like one grand tarot reading for your life, except instead of reading cards, the patriarch is speaking words inspired by the Spirit. The caveat is that the blessings bestowed upon you will only materialize if you obey the will of the Lord. Since I’m, you know, gay and not Mormon now, I think it is safe to say that I have not obeyed the Lord’s will. That means I’m missing out on some choice blessings promised to me, like the one about getting married in the temple and having wonderful children with my husband. It’s a loss I’m willing to take, although at the time of the blessing I was definitely relieved to know that I wouldn’t be Forever Alone™.

I received my patriarchal blessing in late July of 2011, a few weeks before I started my senior year of high school. I went with my mother, stepfather, and stepsister to the patriarch’s house after church. The patriarch and his wife were pleasant people, and we chatted with them for a bit. When it was time for the blessing, my family and I went with the patriarch to a specially prepared room. I sat in a chair, and my family sat behind me while the patriarch stood over me, placed his hands on my head, and began to pray aloud. By the end of the blessing, I was crying silently. The message had been so beautiful, so personal, and so very clearly a loving message from God.

After you receive a patriarchal blessing, the patriarch sends a recording to Church headquarters, where they transcribe the blessing and mail you a copy. My typed blessing is a page and a half, single-spaced. I read it every now and again, but there are three things that I will always remember even without looking at the transcription.

The first thing is that either God or the patriarch was awkwardly mistaken about the nature of my relationship with my father.

“I also want you to know how blessed you are to come through a wonderful mother who has sacrificed much for you, and all that you have at this time is because of your good mother, father and your stepfather, who have sacrificed much for you.”

It was disturbing to hear the patriarch say something that I knew to be false. I was raised by a single mother who had indeed sacrificed a lot for me. But my father? I’d never met the man, and he’d never so much as contacted me, much less sacrificed anything for me. It seemed like an assumption on the patriarch’s part, but what was a patriarch doing sticking his assumptions into a blessing that was supposed to be directly from the Lord? I wanted to hear the rest of the blessing though, so I pushed that thought aside and turned my attention back to the prayer just in time to hear the patriarch say, “Your mother loves you deeply and desires for you to cherish virginity and pureness.” Ooookay. Did she tell you this herself? Ew.

Eventually, the patriarch addressed the matter that was weighing most heavily on my mind and said the second thing that I will always remember:

“I also promise you this day that if you are faithful that you will be able to become anything that you desire to be and that you will be able to seek education at those places where you want to go.”

Jackpot! I mean, not jackpot, because gambling is of the Devil, but this was exactly what I was hoping to hear. I was going to be able to go to college, and I was going to be able to go to the college that I wanted to attend. This was important because the college application process would turn out to be a huge source of contention in my home. My mother wanted me to go to Brigham Young University-Provo, the Harvard of Mormons. Ever since I was a kid, I’d had the same goal. For some reason, however, 17-year-old me was strongly against the idea. I applied only so that my mother would stop pestering me about it.

My dream school was University of Chicago, to which I applied early decision. When I read my acceptance letter online, I burst into tears and then played Coldplay’s “Paradise” at full volume on my computer. I called my mother to tell her the good news, but she was more interested in hearing about when I would find out my status with BYU.

When the BYU decisions were released and I received my acceptance, I was much less enthused. I didn’t want to go. Whenever Church members incredulously asked me why, the best reason I could articulate was that BYU lacked diversity. At the time, it had a Black population of .01%. Yes, there’s a decimal point there. I had spent the first half of my life living in a small Utah town, and I didn’t want that kind of racial isolation again. Although there was an even bigger reason that I would have been uncomfortable at BYU, I wasn’t aware of it at the time.

I later received a full-ride scholarship to Washington University in St. Louis. I loved the school and community when I visited, so that’s where I decided to go. Just as the patriarch had said, I had my choice of school. My mother begged me to go to BYU instead and even arranged an intervention meeting with our bishop so that he could convince me. I wasn’t swayed. This whole ordeal was becoming highly uncomfortable. Why couldn’t my mother just let me go to the school I wanted to go to? Well, she seemed convinced that if I didn’t go to BYU, I would become spiritually lost.

I remember telling her that it was okay, that I wouldn’t leave the church just because I was going to a non-Mormon school. The concept itself was laughable to me. My testimony of the gospel was strong, and it seemed so obvious that I wouldn’t stray from the path. It took a while, but my mother eventually accepted my decision to matriculate at WashU. I stopped going to church within weeks of starting college.

The final paragraph of my patriarchal blessing contains the third message that I’ve always remembered: “Be an example to your race and do not be ashamed of it, for you are indeed a daughter of God, and He loves you.”

If I wasn’t already crying, I was definitely crying when he said those words. I did at times feel ashamed to be Black. I didn’t love myself. How did he know? Truly, this message must have been inspired by God. It wasn’t until college that it occurred to me that the Mormon Church was part of the reason I felt ashamed of my race in the first place. Knowing the way the Church has treated its Black members, I would not be surprised if being told to “be an example to your race” and to “not be ashamed” are standard lines for patriarchal blessings given to Black people. It seemed inspired at the time, when in reality it’s likely that any Black member of the Church feels at least a little unloved.

It was in college that I learned to love my Blackness. My class was 6.9% Black, which may be a small percentage to some, but it was the largest Black community I’d ever had. How lucky I was to be at WashU instead of at BYU, where some people believed that the color of my skin was due to my supporting Lucifer in the premortal existence. My older siblings who had attended BYU had had to deal with racism and ignorance, but I had been spared that fate. It was a good thing, too, because there was another soon-to-be-discovered reason that I would have suffered at BYU.

When I was a senior in high school, I found an old Mormon magazine that contained an article about homosexuality. The article itself was condemning, but the topic stayed in my mind. Same-sex attraction…what a concept. I only had one gay friend, and he happened to be my ride to school. Some of our church peers cried sorrowful tears when he came out.

I knew as surely as I knew God loved me that being gay was not okay. In 2008, I had been a staunch supporter of Prop. 8—the California ballot proposition that aimed to eliminate same sex couples’ right to marry. I was relieved when it passed.

I loved the Church, and I loved the gospel. I was the kind of Mormon who politely dismissed myself from classrooms when teachers showed R-rated movies. At my first and only high school rager, I texted my mother to pick me up because I felt out of place amidst the drinking and smoking. That was me, Straight-Edge Dera, except apparently I wasn’t so straight.

During the spring of senior year of high school, I found myself watching an It Gets Better video created by LGBT students at Brigham Young University. I was in tears by the end of it. I had a strong feeling that there must have been some confusion—God truly did love and accept LGBT people, and somehow this message had just gotten lost along the way. “If there’s any Mormon who’s making a gay person’s life a living hell,” I thought, “then they need to watch this video. Then they’ll understand.”

LGBT was an ever-present thought-worm after that. I made queer friends. I supported LGBT causes. I went to a Pride meeting (for the food, of course). “Love the sinner; hate the sin” wasn’t cutting it for me anymore. I didn’t think being LGBT should be considered a sin in the first place. My interest in all things LGBT was blossoming, and the entire time I thought it was merely because I was a strong ally.

In freshman year psychology, we learned about split-brain patients. There is a bundle of nerves called the corpus callosum that connects the left and right hemispheres of your brain. In split-brain patients, however, this nerve bundle is severed. When scientists observed patients with severed corpora callosa, they discovered that the two hemispheres of the brain have distinct perceptions, personalities, and beliefs.

In one famous scenario, a split-brain patient became angry with his wife. His left hand attacked her. His right hand grabbed the aggressive left hand in order to protect her. In another scenario, a man was asked, “Do you believe in God?” and was told to point to yes or no. His left hand pointed to “yes.” His right hand pointed to “no.”

One brain, two minds.

Sophomore year of college is when I dissociated myself from the Mormon Church and realized I was gay, in that order. I stress the order because I don’t think it could have happened for me any other way. First I had to accept the fact that I no longer believed in the Church or in the God I was taught to revere. Then I could accept the fact that I was sexually attracted to women. I always joke that it happened that way because my brain could only handle one traumatic realization at a time.

While Mormon Brain was calling all the shots, Queer Brain was putting in work. I’m amazed at how much it was able to accomplish without raising suspicion from Mormon Brain. By the time Mormon Brain realized it no longer believed in the Church, Queer Brain had already composed a detailed slide presentation titled “Here’s How You’re Gay Now.” Slide 1 is just a picture of Arden Cho from Teen Wolf.

No longer intimidated and restrained by Mormon Brain’s religious zeal, Queer Brain is finally able to feel at home in its own body. Mormon Brain, on the other hand, is doing some personal development. It has changed its name to Skeptic Brain. It believes in dinosaurs and evolution now.

One brain, two minds. Both are happy to be free.

Being an ex-Mormon is like being able to see both sides of a coin at once. I still remember what it felt like to be Mormon. My mind remembers the Young Women’s oath I recited every week in Sunday School. My hands remember the piano hymns that they memorized for church services. My heart remembers the ache from watching people I love sin and leave the Church.

I have kept all those memories, and they share brainspace with newer memories. Memories of me drinking caffeinated tea for the first time, of me watching my first R-rated movie, of me telling a friend that even though I’ve started saying “shit,” I haven’t gone off the deep end until I’ve said “fuck.” Countless memories of me saying fuck, because fuck it feels good to be free.

I don’t fault my younger self for believing what she believed. My patriarchal blessing is just a relic now, but I still understand why it was so important to me years ago. As peculiar as the blessing seems to me today, I’m glad that it contained the assurance that I should follow my heart during the college admissions process. Without the freedom of a liberal college environment, I might have been a very different person.

Recently I visited some old (Mormon) friends. We were having a meal together. I started to take my first bite and was caught off guard when they asked if we could say a prayer first. I had forgotten the habit of asking God to please bless this food, that it may nourish and strengthen our bodies before eating. Just because I can remember what it’s like to be Mormon doesn’t mean I always do.

These days, I do a lot of sinning. Sometimes it’s getting a tattoo or having guilt-free premarital sex. Sometimes it’s drinking green tea in the morning or wearing a sleeveless shirt. I am my younger self’s antihero. The patriarch never saw it coming.

Comments

Dera this is amazinggg!! <3

Thank you! <3 <3

This is so well-written. Thanks for giving us a window into your life!

This was a very good article. I just have one question if you are someone is willing to answer. I a little familiar with LDS via media, but I am not sure why caffeine is considered a sin. Is it because it’s a stimulant?

It’s just on the naughty list and sorta defies logic (a reoccurring theme within Mormonism!)

There is a section of canonized scripture, Section 189 in the Doctrine and Covenants, which is called the, “Word of Wisdom” and serves as the health code for Mormons. Why you ask? Well because the faith’s founder, Joseph Smith, had a revelation in 1837 (which oddly mirrors the contents of a book known to be in his personal library) which eschews tobacco, strong drink and “hot drinks” which is interpreted as evil caffeinated coffee and tea. Drugs are also assumed to be on the list, although not mentioned by name.

Oddly there’s a provision within the scripture that endorses beer as “barley drinks” being “OK” and Mormons happily enjoyed beer up until the time of prohibition in 1919, but never since. The squeaky clean image became their only missionary selling point in the face of the PR nightmare of polygamy.

There are also suggestions in this scripture about eating fruits and veggies in season and meat sparingly but following this optional. Mormons take a worthiness test by answering questions in order to enter Mormon Temples. They have to do this every two years and if you happen to drink evil tea or coffee or even something stronger you risk gaining access to the Mormon Temple and could miss an important event like say, your daughters wedding. True. No one will bar you from the temple however from eating too much meat!

Hi, thank you! So the short history lesson is that in 1833 Joseph Smith (the person who founded the Mormon Church) advised against drinking “hot drinks.” That’s really vague, so church officials decided he meant no coffee or tea (hot chocolate and non-caffeinated hot teas are fine). Some people extrapolated from that and said it’s because coffee and tea contain caffeine. So there’s always been tension over whether caffeinated sodas and energy drinks, which aren’t hot, are okay. The Mormon Church released a statement in 2012 explicitly saying that caffeinated sodas and energy drinks are okay. Healthier drinks, like green tea, are still not okay. Go figure!

It wasn’t until I left Utah that I realized intensely scrutinizing someone’s morning drink as a marker of their religeous affiliation wasn’t useful in the rest of the country

My first thought when I saw your username was, “Oh, like the brewing company?” and not “Ah yes, Uintah County.” #sacrilege

DERA I LOVE THIS AND YOU THANK YOU FOR WRITING IT!!!!!!!!

<3 <3 <3

This. Is. Beautiful. THANK YOU DERA!!!

Ahh thank you, Ainsley! ^_^ <3

This is one of my favorite essays I’ve ever read. It’s so vulnerable and so funny and so smart and so real and I feel very grateful to have been able to read it. Thank you, Dera.

Oh my goodness :’) Thank you, Heather! <3 <3

Great story; great writing. Thank you for sharing.

This. All of this is so incredibly personal to me, and you hit so many very real things in my life, I feel like I can’t even begin to respond to it all. I grew up mormon, received a patriarchal blessing that really didn’t sit well with me, went to byu, graduated from byu, and it wasn’t until I stopped being mormon that I could even begin to comprehend the fact that I might be gay. (my first love/first heartbreak was actually one of the kids in that video you mentioned, haha) It’s so validating to hear what you went through, and you wrote it all out so perfectly. Thank you thank you. Anyway, cheers to a fellow queer ex mo!

Thank you! Woah that you have a close connection with one of the people in the video! I was just talking with someone about how interconnected the Utah (and California) Mormon community is haha. Kind of like the web in The L Word. Cheers to you too, fellow queer ex-mo!

It is! It’s a small mormon world!

I’m an ex-Mormon too, and while there are some differences in our stories (I left at a younger age and I’m white), I don’t think I’ve ever read anything that echoed my experiences as strongly as this.

Thank you for sharing. This was definitely virtuous, lovely, *and* of good report.

And Praiseworthy ;)

We seek after these things! *fist bump* *secret handshake*

“As peculiar as the blessing seems to me today, I’m glad that it contained the assurance that I should follow my heart during the college admissions process. Without the freedom of a liberal college environment, I might have been a very different person.”

My Mom responding to a period of extended back and forths over my teenage declaration of atheism (read: being real obnoxious at her about her Catholic faith), mentioned regret that she hadn’t encouraged my brother and I to pray every night and all I could think from within my newly found gay but closeted identity at the time was “Thank God you didn’t.”

Hooray for religious autonomy!

Dera, thank you so much for sharing this with us!

Thank you for reading, Laura! :)

Yooo you’re Nigerian fam!

Also why did i JUST realise that the church of latter day saints were mormons..

Yes o! :D

You are a rockstar, Dera!!!! Love this so much. <3

<3 Thank you, Danielle! <3 <3

This is great! A story worth retelling over the years.

Thank you for this, the mormons I knew were always nice people, but tended to keep their Sincere Beliefs on the backburner when it came to nice young obvious Queers like teenage me was, I never would have heard this perspective.

Thank you so much for sharing this with us <3

This was so, so good.

Holy donkey balls that’s exceptional Dera!

If it’s any consolation…you’re so very lucky you had sense enough not to shoulder this bat shit through mid-life and beyond! I wish I could have been so bold. I was up to my eyeballs in high counsel and bishopric before they finally opened to the truth about Santa.

My teenage daughter’s restive brow recently received the same gnarled hands of yon patriarch who read her fortune with the all the same prophetic accuracy. Whatever isn’t fulfilled is all due to your disobedience so here enjoy some guilt with your disillusionment! I chuckled inward as he instructed her never to share the blessings with friends or take it to Girls Camp or quote from it during a prepared talk. “Sure,” I though cynically, “don’t want to find out its identical to everyone elses!

Great story!

> Whatever isn’t fulfilled is all due to your disobedience so here enjoy some guilt with your disillusionment!

Hahaha yup

I love this and you so much! Any time an article can make me catch my breath both from making me laugh and from tugging my heartstrings, I’m all in <3

Aw thank you, Analyssa! <3 <3

Dera!! This is so lovely and beautifully written. Thank you for sharing

Thank you, Al!! ^_^

“Sophomore year of college is when I dissociated myself from the Mormon Church and realized I was gay, in that order. I stress the order because I don’t think it could have happened for me any other way. First I had to accept the fact that I no longer believed in the Church or in the God I was taught to revere. Then I could accept the fact that I was sexually attracted to women. I always joke that it happened that way because my brain could only handle one traumatic realization at a time.”

So. Much. Yes. I left the church at 18 and it would be another 5 years before I was mentally in a place where I could possibly consider the fact that I might be queer. I had to get out from the Mormon strangle hold first before I had any idea that I had options besides what they’d always told me I was on earth to do.

This is wonderful. Thank you for sharing, from one ex-mo to another!

Thanks for sharing! I loved reading your story

This echoes a lot of my feelings about my Catholic confirmation. Thank you for sharing!

It’s so true; I clicked on this article so fast the moment I saw it had something to do with Mormons.

File this under “Things I Didn’t Know About You.”

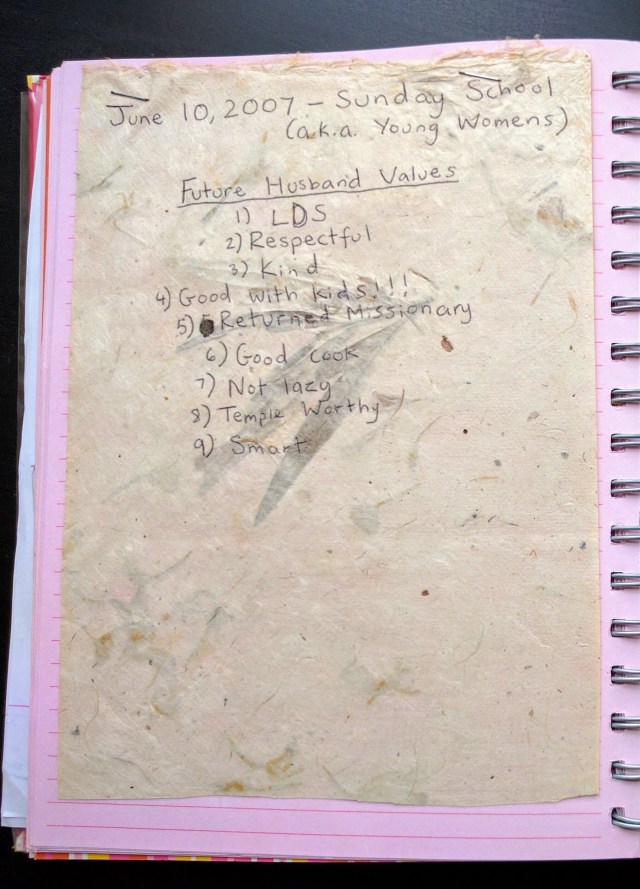

Man, I seeeeriously misread #6 at first. It seemed so off-brand that I zoomed in for a closer look, and realized it actually says “good cook.”

:/ I blame the fancy stationery.

Hahahahaha

Joined to comment on this. So much of this hits home for me, I was raised Mormon and still live at home in Salt Lake City, yet to come out to my parents, though they know I don’t believe, they’ve never been completely okay with it and still condescendingly imply I’ll grow up and come back. But yeah, I clicked immediately when I saw Mormon, and always perk up when I hear the word in conversation, which happens a lot in Salt Lake. Got out just before patriarchal blessing time so I never got that, but I did get the Melchizedek priesthood (adult priesthood), while knowing fully inside that I was trans, so I am morbidly curious of the things people will say when they find out I’m trans. A woman with the priesthood, the horror. Made me feel like a secret agent.

A woman with the priesthood, that’s rad. I’m imagining you now in a secret agent movie. You work alone in the night–dropping meals on doorsteps for families who just had a baby, hanging Christmas lights for old widows–but you always leave a single, pre-blessed piece of white bread behind so people know it was you.

This is fantastic. And I love how you are kind to your younger self.

I’m an ex Mormon and I was also incredibly devout. I got my patriarchal blessing at 10 years old after petitioning the bishop to allow it even though I wasn’t even in Young Womens’ yet. I did the normal interview and was able to express myself like an adult and was given special permission to get mine young. It was freaky and apocalyptic and today the only thing I laugh about is that it said I would “learn to love” my future husband which even then made me think loving a man would be a chore. I was head of seminary. I was a biblical scholar to the point that I tease I should have gotten a master’s degree in it. I would have been a monk in an earlier age the church was so much my life.

But I fell in love with a woman before I left the church. Sometimes I wish it was the other way around — I made life hell for both of us due to internalized homophobia and eventually had a breakdown about losing my entire view of the universe that lasted months. I’m grateful my parents taught me to always get my own revelation because it led to my mental math that made me leave the church. If the Prophet is supposed to be unable to lie in God’s name and he said being gay was wrong but loving my ex felt like the most exquisite heaven I’d ever experienced (and she was very spiritual and was a bit of a punk queer street preacher so it clashed with the whole “that which leads to Christ is of Christ” idea), then the prophet couldn’t be infallible. Therefore all of the church’s teachings were questionable. And it felt like the floor falling out from under me.

I like that you touch on how hard it is to go from being a firm believer to leaving the church. About the level of brainwashing we have to free ourselves from. I vomited the first time I tried to watch a rated R movie and swearing felt like slapping myself in the face. I always felt like I was being watched. But now with time and a lot of good therapy I feel happier and freer than ever before.

Thank you for writing this.

Thank you for sharing your story, Launa. Wow, what an experience. What you said about losing your entire view of the universe is very true. That’s how it felt, and that’s scary! I’m glad you feel good about things now :)

Launa, I very much relate. I was still married when I realized I was queer and fell in love with my best friend. I was ex-communicated and lost all of my friends, marriage, and ended up being homeless. It shattered every notion I had about truth, God, the universe, and everything else.

Even though I’d harbored doubts my whole life, they were so deeply buried that nothing felt validating at first. I was terrified I was doing everything wrong and that I’d suffer the rest of my days on Earth and if I died unrepentant.

It took a lot of time to feel free and not like I had to always look over my shoulder.

Hah. I was so superstitious for years after growing up fundamentalist Christian. It took me a while to say “fuck” and I was terrified of saying “Jesus”, “Christ”, or “Jesus Christ” as profanity. In fact, I routinely asked my wife not to say it. I probably say “fuck” and “Jesus Christ” more than anything else these days and it certainly feels good.

Fantastic read, Dera. Thank you. :)

Thank you, Joanna! :) Haha I was the same…couldn’t even bring myself to say or type “omg”!

Right! Anything with “God” in it was prohibited by my mind too. It was goddamn fucking annoying! :D

This was a beautiful read. Thanks Dera!

This was really great, thank you for sharing Dera :)

DERA I LOVE YOU THANK YOU FOR SHARING YOUR STORY WITH US

This is so great. <3

Thank youuu <3 <3 <3

This was such a beautiful read- funny and touching and heartfelt, and the kindness you show to your younger self is really lovely.

Also, yay for ex-religious queer kids who couldn’t stand fizzy drinks at first! I had the exact same reaction to come, but I could down a pint of cider easily. I also did the whole pre-university “oh no it’s okay I won’t be an atheist!” thing before I left, too. It took me two weeks to give up on finding a church.

Thank you for writing this!

I hugely enjoyed reading this and hope we can see more from you soon!

FUCK YES DERA!

riveting! beautifully written, and such an interesting story!

Beautiful and insightful piece! Loved it!

Thank you for sharing this journey. I love you writing! Hope to see more of it on AS.

It’s such a relief to see so many ex-mormon straddlers in the comments. Leaving the church and “coming out” in secrecy because I was a BYU student shaped a huge part of who I am. While I am so glad to be past that experience. I am always happy to hear other people’s stories. I can’t totally leave Mormonism alone because that’s the culture I grew up in.

Thank you for this beautiful, illuminating story

I’m truly sorry that you were made to feel that you had to measure up and behave a certain way to earn God’s love. =( What’s true is that we’re loved by God, period, and that keeps me going. Thank you for sharing your story! =)

Thank you so much for sharing your story Dera! You write about growing up Mormon in a way that shakes me, it’s so familiar and also so distant. When you write about remembering what it was like to be Mormon, but not fully remembering every detail, that’s what reading your story felt like — I was reminded of the rules and rituals that, at one time, were routine but are now distant memories. I am so happy that I “fell away” from the church when I did, but I’m also grateful for reminders of what my Mormon past was like. Your writing is fantastic and funny and true and I hope to read more from you!

“One brain, two minds. Both are happy to be free.” This is fantastic, this whole article is fantastic, and you’re a linguistics nerd too?! I think I have a new favourite writer. More please!

thank you <3 <3

Dera! You are an awesome human. This was beautifully written. Thank you for this.

Hi, Erica! Thank you very much! :) <3

Dera, this is beautiful. You are such a talented writer and your beautiful heart and beautiful brain (both sides) come through so clearly in this piece.

But also, this was my absolute favorite part:

“When I read my acceptance letter online, I burst into tears and then played Coldplay’s “Paradise” at full volume on my computer.”

You are so wonderful and I’m so glad you’ve joined us here on the dark side <3

Monique ? ? thank you thank you

This piece is so beautiful.

Powerful stuff, Dera. I’m not even Mormon (I was raised non-denominal Christian), but I can relate on so many levels. This part really hit home:

“…First I had to accept the fact that I no longer believed in the Church or in the God I was taught to revere. Then I could accept the fact that I was sexually attracted to women. I always joke that it happened that way because my brain could only handle one traumatic realization at a time.

While Mormon Brain was calling all the shots, Queer Brain was putting in work. I’m amazed at how much it was able to accomplish without raising suspicion from Mormon Brain. By the time Mormon Brain realized it no longer believed in the Church, Queer Brain had already composed a detailed slide presentation titled “Here’s How You’re Gay Now.”

Dera, you are a delight and I want you to never stop writing <3

Ahhh! Fellow queer ex-Mormon here! This essay was fantastic to read and SO VALIDATING. I especially appreciated, “I don’t fault my younger self for believing what she believed. My patriarchal blessing is just a relic now, but I still understand why it was so important to me years ago.” I also loved being your younger self’s antihero; sometimes I’m still freaked out by how freaked out younger me would have been by older me, but I’m so happy I’m me now, knowing that my younger self is going to be okay(-ish) one day. My patriarchal blessing is mostly about how unless I follow the teachings of Christ my life will be extremely extremely extremely hard and I’ll cry a lot, so like….fair, I guess? Anyways, thanks for this lovely and inspiring personal essay. I appreciate it so so much.

Thank you SO much for writing this. I often forget there are so many of us queer ex-Mormon women and it makes my heart happy to find more. So much of my life has been shaped by the Church (whether it’s things I learned and kept, or things I learned from the trauma I experienced there) and reading this made me feel better about that. I never received my Patriarchal blessing but sometimes I wish I had, even still, even with how I feel about the Church.